Upper respiratory tract infections are a common reason for consultation in family practice. Although the recommendation not to prescribe antibiotics for uncomplicated upper respiratory infections made Smarter Medicine’s top 5 list for outpatient general internal medicine, they remain one of the most common reasons for prescribing an antibiotic. This may be related in part to the lack of a stringent definition of when an upper respiratory tract infection is “uncomplicated” and when “complicated” disease is suspected and must be treated with antibiotics.

Upper respiratory tract infections are a common reason for consultation in family practice. Although the recommendation not to prescribe antibiotics for uncomplicated upper respiratory infections made Smarter Medicine’s top 5 list for outpatient general internal medicine, they remain one of the most common reasons for prescribing an antibiotic. Among other things, this could be related to the lack of a stringent definition of when an upper respiratory tract infection is “uncomplicated” and when a “complicated” disease is suspected and must be treated with antibiotics – in contrast to urinary tract infections, for example.

Acute sore throat is the most common leading symptom of acute tonsillopharyngitis. Accompanying symptoms may include fever, aching limbs, headache, cold, cough, difficulty swallowing, abdominal pain, and nausea and vomiting.

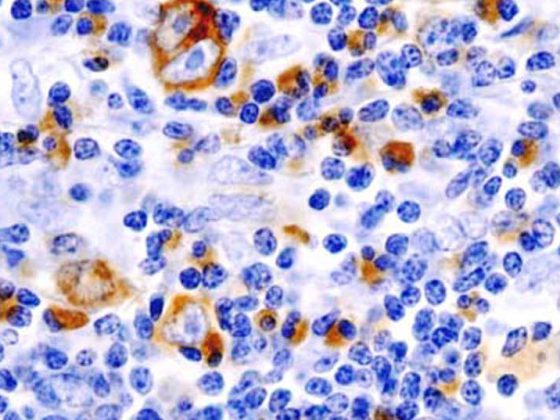

This is usually a self-limiting infection caused by various viral pathogens, of which we would like to mention here only the Ebstein-Barr virus (EBV) in particular. The most common bacterial pathogens include Fusobacteria and Mycoplasma, in addition to β-hemolytic streptococci of groups A (Strep A), C, and G. While the former are most commonly detected as appropriate rapid tests are available, the role of Fusobacteria is likely to be underestimated as they require specialized culture media which are rarely requested. In a US study, Fusobacteria were even the most common pathogen [1]. Not infrequently, several germs can also be detected, although it is not always clear which germ causes the symptoms and which merely colonize the oral flora.

Furthermore, sexually transmitted pathogens such as the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), chlamydia and gonococci are always a possibility. In young children, the differential diagnosis is extended to include specific pathogens and clinical pictures (e.g., epiglottitis caused by the pathogen H. influen-zae), which will not be discussed in detail in this article.

If the course is prolonged, non-infectious causes must also be considered: Gastroesophageal reflux disease, physical or chemical irritation (for example, from the use of tobacco products, snoring, or drug toxicity, especially ACE inhibitors and chemotherapeutic agents) and inflammatory diseases (for example, Kawasaki’s disease and other vasculitides), endocrinological diseases (for example, acute thyroiditis), as well as neoplasms in the oral pharynx.

Complications

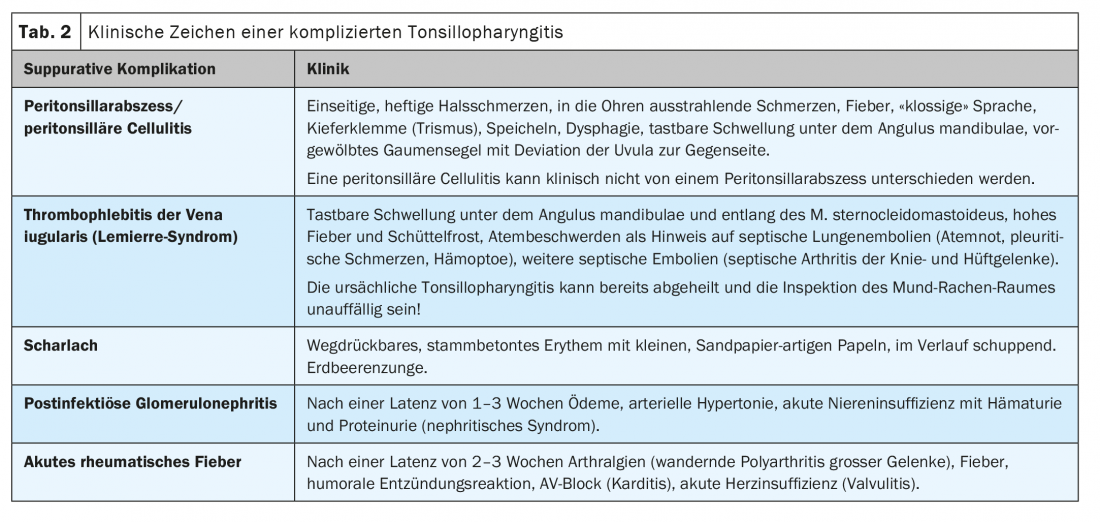

Complications of acute tonsillopharyngitis are fortunately very rare. A distinction can be made between immunologic and suppurative complications:

Immunologic complications include acute rheumatic fever, acute postinfectious glomerulonephritis, scarlet fever, and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. Immunologic complications are caused by certain strains of Strep A and primarily affect children. Acute rheumatic fever is very rare with an annual incidence of <2/100,000 in developed industrialized countries. Scarlet fever and postinfectious glomerulonephritis, although more common, are usually self-limiting.

Suppurative complications include, on the one hand, locally invasive diseases ranging from peritonsillitis (peritonsillar cellulitis) and peritonsillar abscess to thrombophlebitis of the iugular vein (Lemierre’s syndrome) and necrotizing fasciitis, and, on the other hand, otitis media and sinusitis. The latter, although more common, represent separate clinical entities, which we will not discuss in detail here. Peritonsillar abscess occurs primarily in young adults, with an annual incidence of up to 160/100,000, and affects 0.2% to 0.5% of patients with acute tonsillopharyngitis [2]. Suppurative complications show a similar spectrum of pathogens as in uncomplicated tonsillopharyngitis, with Fusobacteria outranking Streptococci here as well [3]. Viral pathogens, especially EBV, can also cause suppurative complications.

Diagnosis

Clinic

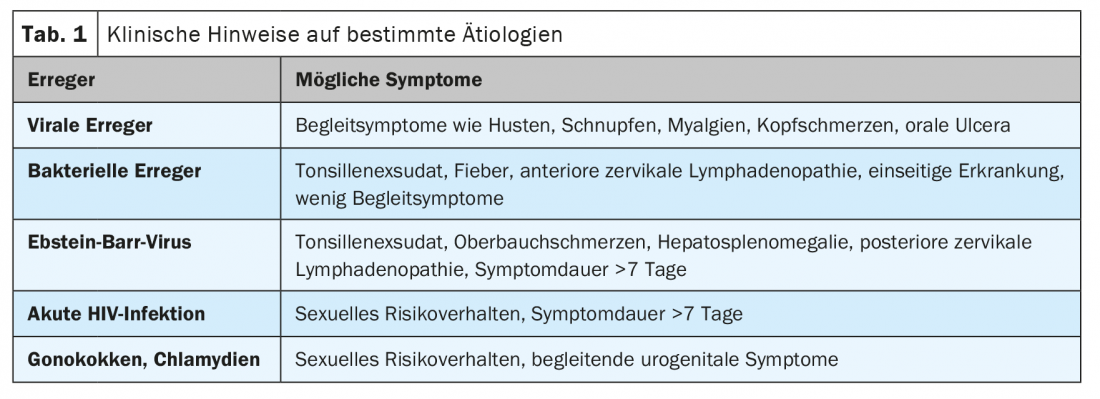

The diagnosis of acute tonsillopharyngitis is clinical. Although the etiology cannot be determined on the basis of history and clinic alone, it seems important to record corresponding indications and to include them in the differential diagnostic considerations (Table 1).

In the medical history, accompanying symptoms, symptoms of possibly already manifested and life-threatening complications as well as risk factors, in particular nicotine abuse and sexual risk behavior, should be inquired about (Tab. 2). At a minimum, a local status should be obtained in the physical examination (inspection of the oropharynx, palpation of the soft tissues of the neck) to identify manifest complications (Tab. 2). Depending on the situation and history, further targeted examinations may also be indicated: pulmonary and cardiac auscultation, abdominal palpation, complete lymph node status, and otoscopy. The structured recording of vital parameters, especially blood pressure, is useful in any consultation anyway in terms of cardiovascular prevention.

Microbiology, laboratory and imaging diagnostics

The value of rapid Strep A antigen tests in throat swabs is increasingly being critically questioned in terms of the epidemiology outlined, and is now only explicitly recommended in pediatrics [4]. Other pathogens can be detected in the culture, in particular β-hemolytic streptococci of groups C and G. It should be noted that a selective culture medium is required for the detection of Fusobacteria, which is not used as standard and must be explicitly requested. Since therapy is based on the clinic and less on pathogen detection, throat swabbing (both antigen rapid and culture) is inconsequential and, in our opinion, should not be performed as standard practice. Smear testing is also questionable in children, especially since even the Association of Cantonal Physicians no longer recommends specific preventive measures such as school exclusion in their latest recommendations [5].

If sexually transmitted diseases are suspected, appropriate PCR tests (chlamydia, gonococci) or serological screening tests (HIV) are available. If infectious mononucleosis is suspected, the diagnosis can be confirmed by both rapid antigen testing and serology, although both tests have poor sensitivity during the first week of illness.

Laboratory chemistry tests, particularly blood count and CRP, do not significantly increase diagnostic accuracy and should not be routinely determined [6]. CT of the soft tissues of the neck may be helpful in differentiating peritonsillar cellulitis from peritonsillar abscess or other invasive infections, but this is also not routinely indicated.

Therapy

Symptomatic therapy

Symptomatic therapy focuses on analgesia, and paracetamol and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be used in particular. Metamizole has not been tested in this indication and should not be used in the first line. Supportive local anesthetics in the form of sprays for local application can be used.

A systematic review with meta-analysis of multiple randomized trials showed that corticosteroids do reduce the time to symptom relief by 2-7 hours compared with placebo. However, no difference was demonstrated in symptom freedom at 24 and 48 hours. Also, no reduction in the number of days absent from work or antibiotic prescriptions was demonstrated. Most studies used dexamethasone per os at a dose of 10 mg (0.6 mg/kg in children). Whether the use of corticosteroids is appropriate in individual cases should be discussed with the patient according to the principle of participatory decision making [7].

Antibiotics

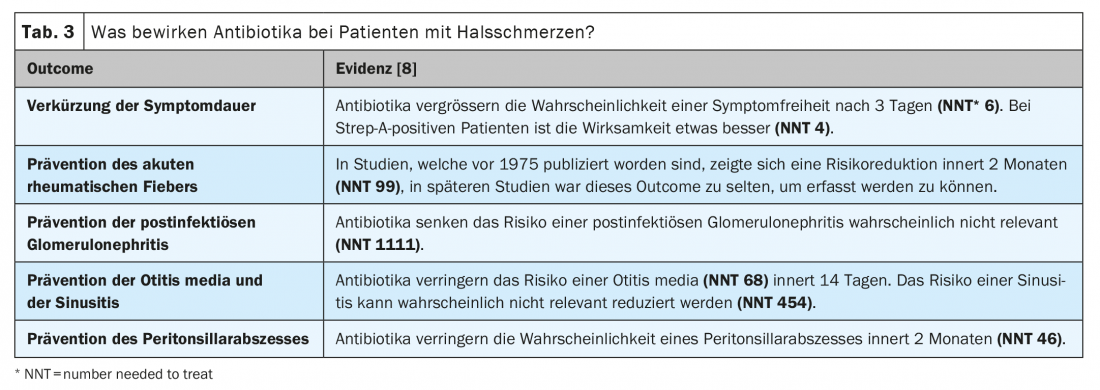

The use of antibiotics has also been reviewed several times in systematic reviews in the Cochrane Library [8]. A compilation of the results is shown in Table 3 . It should be noted that the work includes numerous studies from the 1950s. To what extent findings from these studies are still valid in today’s epidemiological context is unclear. A subgroup analysis of the more recent studies was performed only for the outcome “rheumatic fever.”

The best evidence of efficacy is for symptom duration reduction. However, since symptomatic therapies are available for symptom reduction, we do not believe this is an adequate indication. Although antibiotics can prevent certain complications, the rarity of these complications means that many patients (using peritonsillar abscess as an example: 46) must be treated unnecessarily to prevent a single complication. By comparison, in uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women, approximately 25 patients must be treated to prevent pyelonephritis.

Various European guidelines no longer consider the prevention of suppurative and immunologic complications as an adequate indication for antibiotic therapy. A review paper on this topic was also recently published in Switzerland with the recommendation to use antibiotics only in cases of manifest or impending complications (strictly unilateral, severe tonsillitis, unusual course, poor general condition, immunosuppression, advanced age, and significant comorbidities) or risk factors for relevant immunologic complications (scarlet fever, condition after acute rheumatic fever, immigration from developing countries) [9].

However, since in clinical practice we have to take into account not only medical-scientific factors but also the expectations and preferences of our patients, the use of antibiotics should be discussed with the patient according to the principle of participatory decision-making, whereby patient autonomy must of course be weighed against the increasing problem of anti-biotic resistance.

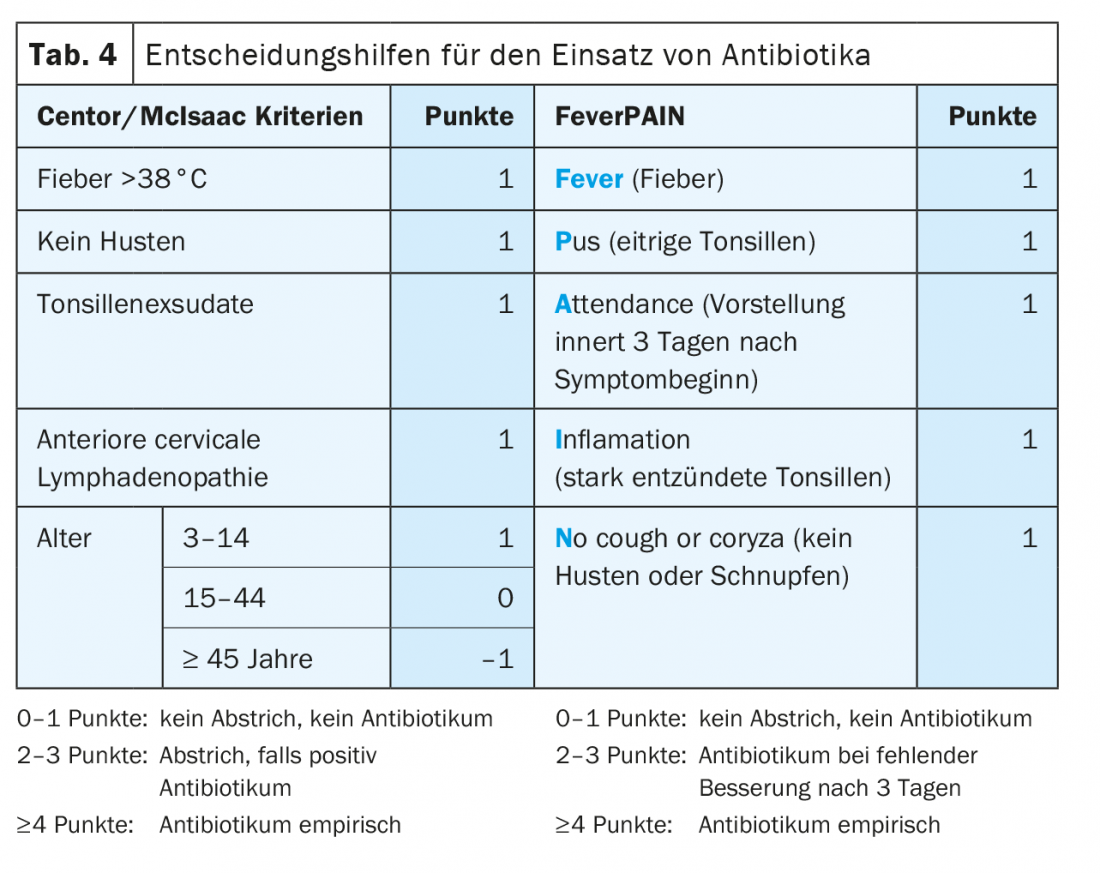

The Centor criteria, which estimate the probability of Strep A infection, have been used as a decision-making tool for 40 years now. According to McIsaac, these can be supplemented with an age criterion (Table 4) . Depending on the guideline, a Strep A rapid test should be performed from a score of 2-3 or empirical treatment from a score of 3-4. It should be noted, however, that although the Centor criteria correlate significantly with the risk of suppurative complication, they lead to many false-positive results because of their moderate specificity (approximately 68%). The somewhat younger and less well-known FeverPAIN score (Table 4) does not perform any better [6].

If antibiotics are used, penicillin or amoxicillin should be prescribed in the first instance. A 5-day therapy duration is not inferior to the common 10-day therapy duration. In case of penicillin allergy, an oral cephalosporin, macrolide or clindamycin may be used as an alternative. Broad-spectrum antibiotics such as co-amoxicillin should be avoided in uncomplicated illness. To avoid a duration of therapy differentiated according to age and agent, the Swiss Society of Infectious Diseases generally recommends 6 days of antibiotic therapy for simplicity [10].

Conclusion

Tonsillopharyngitis is a common and usually self-limited condition. Common treatment strategies date back to the 20th century and focus on the eradication of group A streptococci, which can cause serious immunologic complications. However, these are rare and antibiotics should now only be used when complications are manifest or imminent.

Take-Home Messages

- Acute tonsillopharyngitis is a common and usually self-limiting disease.

- The treatment depends on the clinic. Pathogen detection by rapid Strep A antigen test or culture is not necessary in uncomplicated disease.

- In case of corresponding risk factors, a clarification for sexually transmitted diseases should be carried out (chlamydia and gonococcal PCR, HIV screening test).

- The Centor/McIsaac criteria are nonspecific and result in many unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions.

- Antibiotics should now be used only in cases of impending or manifest complications (strictly unilateral, severe tonsillitis, unusual course, poor general condition, immunosuppression, advanced age, and significant comorbidities) or risk factors for relevant immunologic complications (scarlet fever, condition after acute rheumatic fever, immigration from developing countries).

Literature:

- Centor RM, Atkinson TP, Ratliff AE, et al: The Clinical Presentation of Fusobacterium-positive and Streptococcal-positive Pharyngitis in a University Health Clinic. Ann Intern Med 2015; 162: 241; doi: 10.7326/M14-1305.

- Little P, Stuart B, Richard Hobbs FD, et al: Predictors of suppurative complications for acute sore throat in primary care: prospective clinical cohort study. BMJ 2013; 347: 1-14; doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6867.

- Klug TE: Peritonsillar abscess: clinical aspects of microbiology, risk factors, and the association with parapharyngeal abscess. Dan Med J 2017; 64.

- Pediatric Infectious Disease Group of Switzerland. Recommendations of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Group of Switzerland for the diagnosis and treatment of acute otitis media, sinusitis, pneumonia, and tonsillopharyngitis in children 2010; www.pigs.ch/pigs/05-documents/doc/reco2010-d.pdf (last accessed August 5, 2021).

- Association of Cantonal Physicians of Switzerland. Recommendations for (pre)school exclusion for communicable diseases and parasitoses 2020; www.vks-amcs.ch/fileadmin/docs/public/vks/Schulausschluss__def_20200505_d.pdf (last accessed July 27, 2021).

- Helfenberger L, Fischer R, Giezendanner S, Zeller A: Risk factors for peritonsillar abscess in streptococcus A-negative tonsillitis: a case control study. Swiss Med Wkly 2021; 151: w20404; doi: 10.4414/smw.2021.20404.

- Sadeghirad B, Siemieniuk RAC, Brignardello-Petersen R, et al: Corticosteroids for treatment of sore throat: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ 2017; 358: j3887; doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3887.

- Spinks A, Glasziou PP, Del Mar CB.: Antibiotics for sore throat. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013: CD000023; doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000023.pub4.

- Hofmann Y, Berger H, Wingeier B, et al: Treatment of streptococcal angina. Swiss Med Forum 2019; 19: 481-488.

- Huttner B, Albrich W, Berger C, Boillat Blanco N: Pharyngitis. SSI Guidel 2020; https://ssi.guidelines.ch/guideline/2408/9530 (last accessed August 5, 2021).

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(11): 16-19