At first glance, all exanthemas look the same. But there are many possibilities: Is it incipient drug exanthema, reactive exanthema, viral exanthema, disseminated contact allergy? A combined clinical, laboratory, and pathology system is designed to help the reader make a diagnosis, initiate the correct therapy, and discontinue and replace suspected medications. Or even to do nothing.

The development of acute exanthema is dramatic and sometimes threatening to the patient. It often occurs at an unfavorable moment, postoperatively, during hospitalization, in the course of a necessary antibiosis, an infection. It is often associated with accompanying symptoms, general symptoms, and abnormal laboratory and blood work. For the clinician, the question at that moment is whether it is incipient drug exanthema, reactive exanthema, or some other skin condition, whether the medication may be continued, or which drug may be to blame. People often assume an allergic reaction, leading to far too high a rate of drug allergy diagnosis. In a retrospective study, 612 hospitalized patients with acute exanthema were shown to have reactive or other exanthema in almost half [1]. A systematic approach is required here and the help of the dermato-allergist is called for. In some cases, the diagnosis can only be made by combining history, clinical examination, laboratory, histopathology, and skin testing.

The anamnesis

The first thing to know is the exact day, at best with the help of the care curves: when and where did the exanthema start, with itching or not? Have any new medications been started or restarted after an interruption? Has surgery been performed? After how many days, minutes, or hours did the symptoms begin? Have herbal medicines been taken, contrast agents administered? Are associated symptoms present, fever, joint pain, gastrointestinal symptoms present? Has there been a prior bout of flu, another infection, or multiple infections in the past? How long ago? Did unprotected sexual intercourse take place? Is there a risk of HIV, have there been foreign visits, have there been injuries, animal bites or stings?

The investigation

Here, attention should be paid to the distribution of the exanthema (localized/generalized/symmetrical), the primary florescences: are they maculopapules, papulovesicles, wheals, pustules, blisters, an erythema? What is their size? Are accompanying symptoms such as oozing, crusts, petechiae present? Are the mucous membranes affected, the flexures, perianal, genital, palmoplantar? What is the dynamic? Can bubbles be displaced (Nikolsky phenomenon)? Other features such as confluent, erythrodermic, cocardiform lesions? Is there swelling of the lymph nodes?

The histopathology

Histopathology is an important tool for distinguishing the different drug exanthems, but at best it can also help diagnose contact allergic, reactive viral or bacterial exanthema, provide information about the presence of vasculitis, neutrophils, epidermal involvement and epidermal necrosis (a sign of fulminant development into possible toxic epidermal necrolysis [TEN], or staphylococcal toxin-associated severe blistering). The presence of neutrophils indicates a response to steroids, eosinophilia near the epidermis indicates an allergic or autoimmune bullous event, vasculitis without eosinophilia indicates a reactive event (viral, streptococcal, rickettsial) or systemic autoimmune disease.

The tests and results

The basic examination includes clinical chemistry (liver values: drugs, viral), blood count: lymphopenia (viral disease), leukocytosis (infection, vasculitis, hypersensitivity syndrome), eosinophilia (allergy), and CRP (infection, vasculitis). Specific IgM only make sense in case of infections in the first four weeks and in case of important information about possible infectious pathogens (e.g. because of pregnant women) or in case of specific suspicion of a pathogen like HIV, EBV or parvovirus B19. Since viral exanthema occurs relatively late (in some cases after 2 weeks, infectious reactive in some cases after 3 weeks), the seroconversion with detection of spec. IgG as early as 1-2 weeks after onset of exanthema, possible about four weeks after infection. In streptococcal infections, antiStrepto-dornase B-AK is more indicative of an active infection than ASLO-AK, which then persists more as a seromarker. Further specific examinations such as X-ray or quantiferon should only be added if there are corresponding clinical symptoms (cough, night sweats), indications from histology or persistence of the exanthema (tuberculid reaction, lichen scrofulosorum e.g. = Tbc).

Skin testing/allergy laboratory

In principle, all drugs can cause allergies of the immediate or late type. Thus, the classification of the exanthema helps determine the type of testing; intradermal, scratch and prick testing for immediate type reactions and for late type scratch-patch or epicutaneous testing with readings after 24 and 48 hours. However, standardization of testing is poorer the less frequently the drug has been described for an allergic reaction. Similarly, sensitivity can vary widely, but fortunately is very high for commonly accused drugs (penicillins, novaminsulfon, heparins, imidazoles, and others). Skin testing is not recommended in very severe drug reactions to avoid a theoretical recurrence of the exanthema. However, recent studies showed hazard-free skin testing in TEN and Steven-Johnson syndrome (SJS).

Another test option is to perform lymphocyte transformation testing in specialized laboratories (well standardized, but proven especially for antibiotics, semi-quantitative evaluation). Basophil activation assays and histamine release of basophils after incubation with drugs or natural allergens (plants, insect venoms) also show different reliable results. Specific IgE testing finds some immediate-type allergy to penicillins and cephalosporins, but no late-type allergy.

Drug exanthema and reactive exanthema

Based on a prospectively collected clinical survey, histopathologic examination, testing, and laboratory in patients with initial symptoms of generalizing exanthema, we were able to identify clear differences between allergic and reactive exanthema [2].

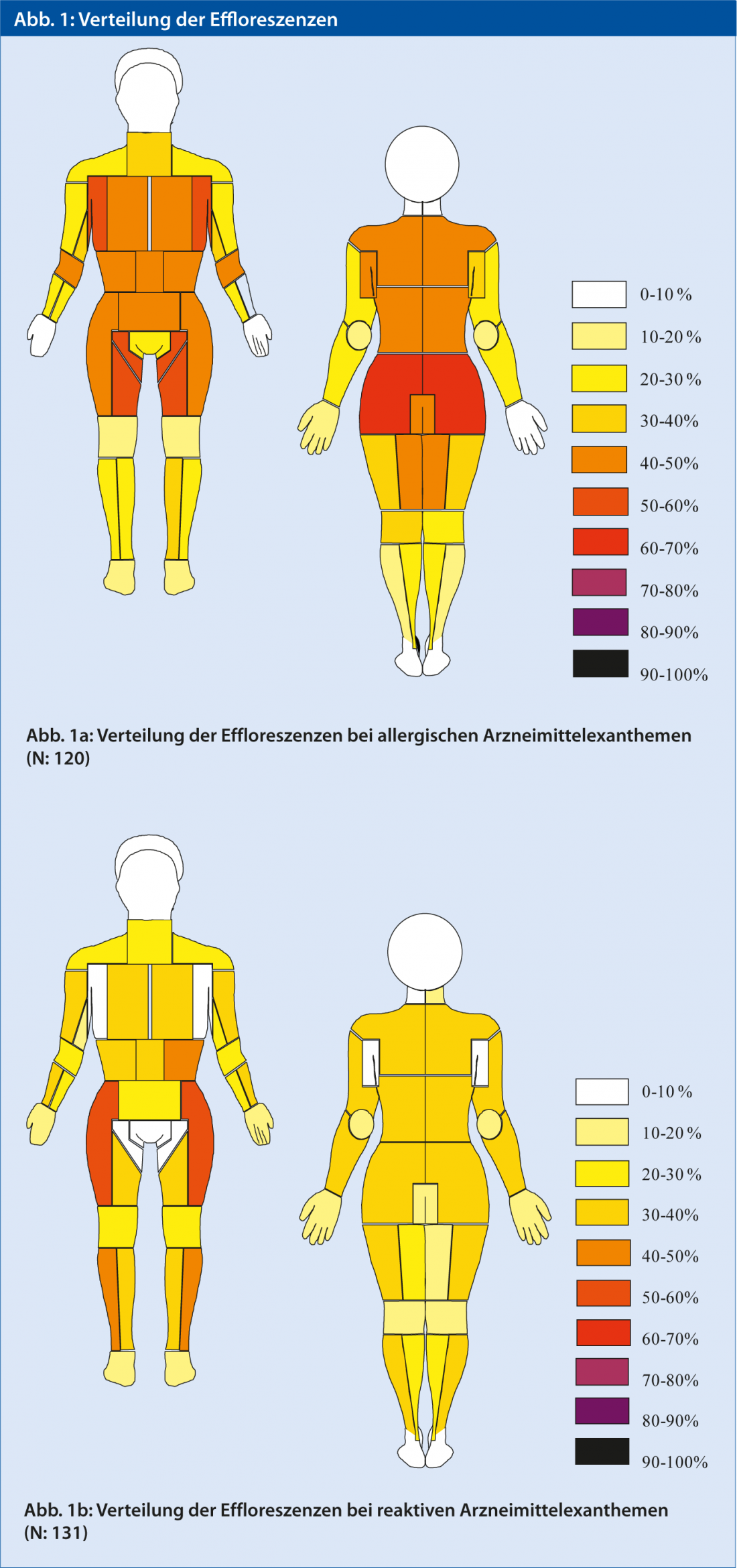

More frequently, the allergic reactions to drugs show onset and accentuation of the flexures (axilla, inguinal, ulnar, and popliteal), inner arms and legs, buttocks, and neck ( Fig. 1a). The reactive exanthemas, on the other hand, are found more on the outer extremities, palmoplantar and flanks (Fig. 1b). [3]. Histopathology provides a decisive clue with a stronger involvement of the epidermis and eosinophilic granulocytes close to the epidermis. Nevertheless, the various drug exanthems and also the reactive exanthems differ from each other by activation of individual cell populations and the drug exanthems in particular by partly characteristic epidermal changes. The laboratory may show eosinophilia in the drug allergies. An increase in liver enzymes can also occur in viral infections. Finally, skin tests and laboratory methods must be used to confirm or rule out allergies to medications started during this period.

Various drug exanthema.

Three questions arise here:

- Is it a dangerous reaction?

- What form of drug exanthema is it?

- What is the triggering drug?

Although certain drugs predispose to certain forms of exanthema, in principle all drugs and also herbal products or additives can lead to any form of drug exanthema. However, the usual suspects are antibiotics, analgesics, antiepileptics, and contrast agents. The drugs to be suspected have been given either 1-2 days ago in case of pre-existing sensitization (urticaria: within 2 hrs, contrast often after 12 hrs) or after seven (acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis [AGEP], allergic vasculitis) to ten days (maculopapular exanthema, TEN, SJS, eczema-type drug exanthema). The exception here is the “drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic signs” ([DRESS], formerly: hypersensitivity reaction), which occurs two to twelve weeks after the start of medication (usually antiepileptic drugs).

It is important at this moment to recognize potentially severe drug reactions, namely AGEP, DRESS, SJS, and TEN. The latter is associated with a mortality of up to 50%. While DRESS is characterized by markedly high eosinophilia, hepatic elevations, and involvement of other organs (heart, lungs), the others differ clinically or histopathologically.AGEP usually begins with universal erythema on the trunk and face and pustules no larger than the size of a pinhead, often discovered only histopathologically because of their small size, and neutrophil-rich inflammation indicating a response to systemic steroids. SJS and TEN are defined by the area of blistering (SJS <10%, SJS/TEN overlap >10%, TEN >30%) and begin with flat (as opposed to erythema exsudativum multiforme [EEM]) targetoid macules with dusky centers and early involvement of the face and mucous membranes. An early biopsy may reveal the expected extent of epidermal necrosis with perishing basal keratinocytes without much inflammation and thus this diagnosis. However, maculopapular exanthema(Fig. 2) and SDRIFE are the most common, which is almost always maximal on the buttocks, inguinal, and genitoanal.

In all drug exanthemas with a selection of possible triggers, severe drug exanthemas, and the need to elicit alternative medications, allergologic workup is indicated beginning four weeks after exanthema(Fig. 3).

Fig. 2: Flexural maculopapular drug eruption.

Fig. 3: Positive skin test (scratch-patch) after 24 hrs for simvastatin.

Reactive exanthema

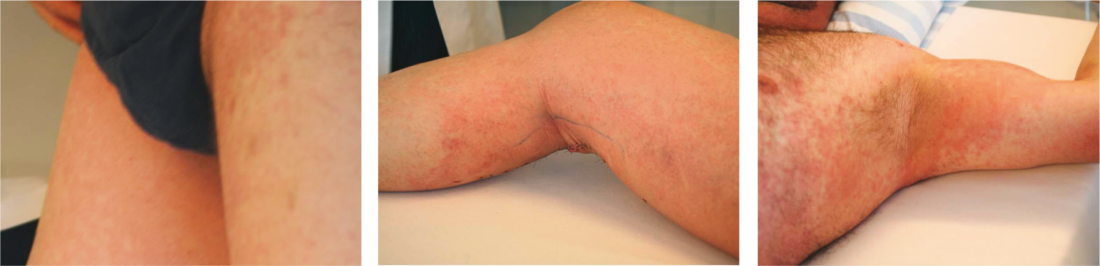

Many viral diseases and streptococcal infections show a typical pattern of single morphs (e.g., morbilliform, scarlatiniform, etc.) and a typical sequence with a defined latency to the time of infection, as well as a distribution pattern that often corresponds to that of other reactive exanthemas(Fig. 4). It is mainly the viral infections as well as the EEM that can also go to the mucous membranes, show palmoplantar lesions and affect more the outer sides of the extremities. Except in the case of the EEM, the trunk is also often involved (see above). Certain viral exanthems such as measles with the strong reaction on the mucous membranes and the onset of the exanthema behind the ears, or parvovirus B 19 with the reticular petechial seeding on the extremities(Fig. 5) are quite characteristic. Evidence is also provided by elevated CRP, monocytosis and lymphopenia in the blood count, and reactive lymphocytes. The histopathology of viral exanthema shows mostly superficial inflammation with reactive lymphocytes and, in contrast to drug exanthema, little involvement of the epidermis. Hemorrhage and vasculitis are not uncommon.

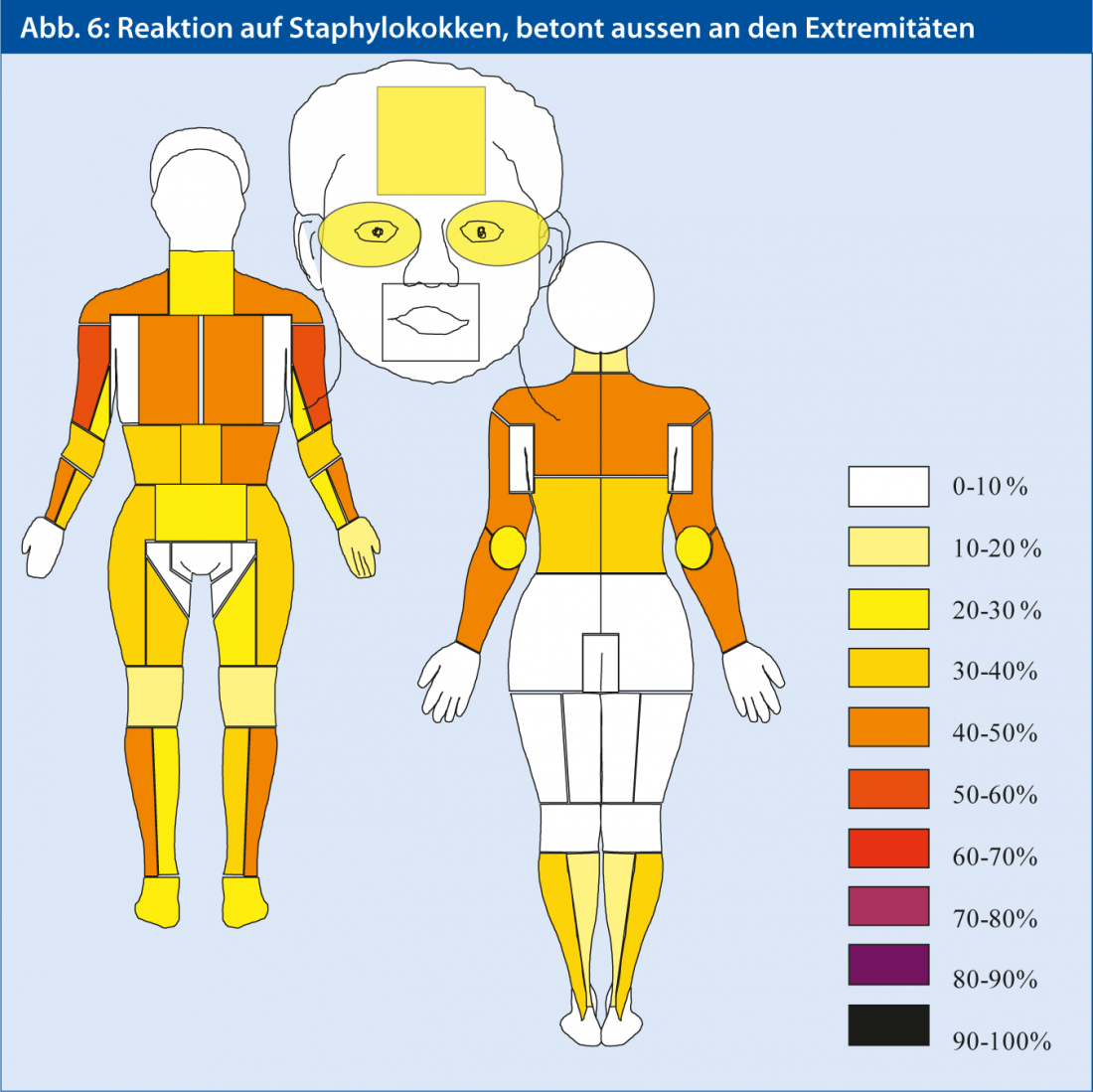

In addition, we often find other situations and bacterial pathogens, which lead to a skin reaction. Who is predisposed to such reactive exanthema of non-viral etiology? We often find the reactive exanthema in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, repeated bowel surgery, superinfections of the skin, or recurrent infections. In this case, the bacterial antigens or toxins lead to an “infectious allergy” through presumed sensitization and recognition by the adaptive immune system. Reactions are urticarial, maculopapular, eczematous, or multiform and occur rapidly (1 to several days) after a procedure or when antibiotics are started. Staphylococci occupy a special position, leading to a seeding of eczematous or confluent maculopapular efflorescences in superinfected wounds and dermatoses (so-called staphid), similar to a scattering contact dermatitis(for distribution, see Fig. 6). Histopathologically, the infiltrate is deeper in reactive bacterial exanthema than in drug exanthema, in recruitment of lymphocytes from deeper dermal vessels, and especially in staphylococcal-triggered reaction (where eosinophilic granulocytes are also present). Biopsied directly at superinfection, of course, one finds a neutrophil-rich infiltrate and/or evidence of impetigo.

Fig. 4: Viral exanthema, with petechiae, sparing the flexures.

Fig. 5: Characteristic lightning figure-like exanthema in parvovirus B19.

Limitation

Difficulties in diagnosis nevertheless remain, clinically in erythroderma, which could be the expression of a generalized dermatosis such as eczema or lymphoma. Moreover, some drug exanthems, especially DRESS syndrome, are expressions of viral reactivation and show their own laws especially with involvement of internal organs, or drug exanthema is dependent on the presence of a viral infection (day 10 exanthema in EBV with penicillin) [4]. Other problems include the lack of standardization or data on sensitivity or specificity of allergy skin testing or LTT for many drugs. Treatment with steroids can greatly alter the histopathological picture and lead to a rapid disappearance of eosinophil granulocytes, neutrophils and vasculitis.

Conclusion

We have often relied on our instinct in the evaluation of exanthema and have often made the right decision. A systematic approach and the interplay of anamnesis, collection of clinical symptoms, distribution patterns and characteristics of the skin lesions make it possible to set an early course and distinguish between allergic and other exanthemas. Further pillars of the clarification are the analysis of skin biopsies, laboratory tests and, at a later stage, allergological clarifications. Medications should always be taken into account, but patients with recurrent infections and chronic intestinal inflammation, for example, also experience non-allergic reactions.

Distinguishing drug reactions from reactive exanthema helps in the proper choice of therapy and medications. Prompt action on drug allergies can significantly shorten severe skin and mucosal reactions and improve prognosis.

Mark David Anliker, MD

Literature:

- Heinzerling LM, et al: Is drug allergy less prevalent than previously assumed? A 5-year analysis. Br J Dermatol 2012; 166: 107-114.

- Anliker MD, et al: Different distribution and clinical patterns in allergic drug reactions vs. reactive/parainfectious exanthemas. Posterpresentation at Annual meeting of the SGDV 2012, Berne, Switzerland.

- Winnicki M, et al: A systematic approach to systemic contact dermatitis and symmetric drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema (SDRIFE): a closer look at these conditions and an approach to intertriginous eruptions. Am J Clin Dermatol 2011; 12: 171-180.

- Descamps V, et al: Saliva Polymerase Chain Reaction Assay for Detection and Follow-up of Herpesvirus Reactivation in Patients With Drug Reaction With Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS). JAMA Dermatol 2013; 149: 565-569.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2013, issue 4; 10-14