The treatment of patients in pulmonary clinics can include not only diagnostics and therapy, but also assistance in dying. In addition to lung cancer, COPD and pulmonary fibrosis are the most common causes of death in patients receiving non-intensive care.

The treatment of patients in pulmonary clinics includes not only diagnosis and therapy of underlying diseases, but also assistance in dying. Among non-intensive care patients, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and pulmonary fibrosis are the diseases that most frequently lead to death, in addition to lung cancer. Patients with lung disease exhibit distressing symptoms such as shortness of breath, anxiety, or weakness early in the course of the disease, even in the presence of non-malignant disease. Therefore, palliative care expertise is essential in a pulmonary clinic.

The assessment of symptom burden, the prescription of symptom-relieving medications, counseling regarding palliative structures, and the involvement of other professions such as palliative care, psychologists, social services, or hospice services are the focal points of palliative medical consultations. For patients with malignant, but also non-malignant, incurable and progressive diseases, treatment by specialized palliative care providers may be required in accordance with the available structures within the framework of a palliative consultation service or on a palliative ward if the symptom burden is high. Even if all available options for symptom relief are taken, symptoms may persist and cause serious distress to the patient. At this point in the care of terminally ill patients, palliative sedation represents an option for symptom relief in cases of refractory symptoms and unbearable suffering. The purpose of this article is to explain the concept of palliative sedation (PS) and to provide guidance on indications as well as implementation. It is not uncommon for the decision-making process for PS to challenge even experienced palliative care providers. This article also aims to explain the differences between PS and physician-assisted suicide in this ethical tension, as well as to address the need for documentation and education.

Definition of “palliative sedation” (PS) and frequency

The comparison between different studies on PS (in English: “continuos deep sedation until death”) is difficult because there is no uniform definition for palliative sedation so far. There is wide variation in the use of sedatives as well as the depth of sedation. Controlled studies are almost completely lacking. Even at the guideline level, the definition is not clearly articulated [1,2]. A commonly used definition is the following: “PS is the use of specific sedatives to relieve intolerable suffering from refractory symptoms by reducing the patient’s level of consciousness” with the following addition: “in a manner that is ethically acceptable to patients, families, and staff” [3]. The Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association defines palliative sedation as the “supervised use of medication that causes various degrees of unconsciousness, but not death, to relieve refractory and intolerable symptoms in immediately dying patients.”

Because of the inconsistent definition, it is difficult to collect valid data on the use of palliative sedation. This is certainly complicated by the large variability in the implementation of PS [4]. For Germany, it is assumed that PS is used for 34% of all patients on a palliative care ward; internationally, the figures vary from 10 to almost 55%. In countries such as the Netherlands, Belgium, and Switzerland, the use of palliative sedation is thought to account for 12-18% of all non-sudden deaths. Data regarding the frequency of palliative sedation use in pulmonary clinics do not exist [5].

Over the past decade, the number of guidelines related to PS has increased, although recommendations regarding the definition and implementation of PS are inconsistent. We present here mainly recommendations from the European Association of Palliative Care (EAPC) guideline, with additions of content from other guidelines [1–3,6,7].

Definition “Unbearable Suffering

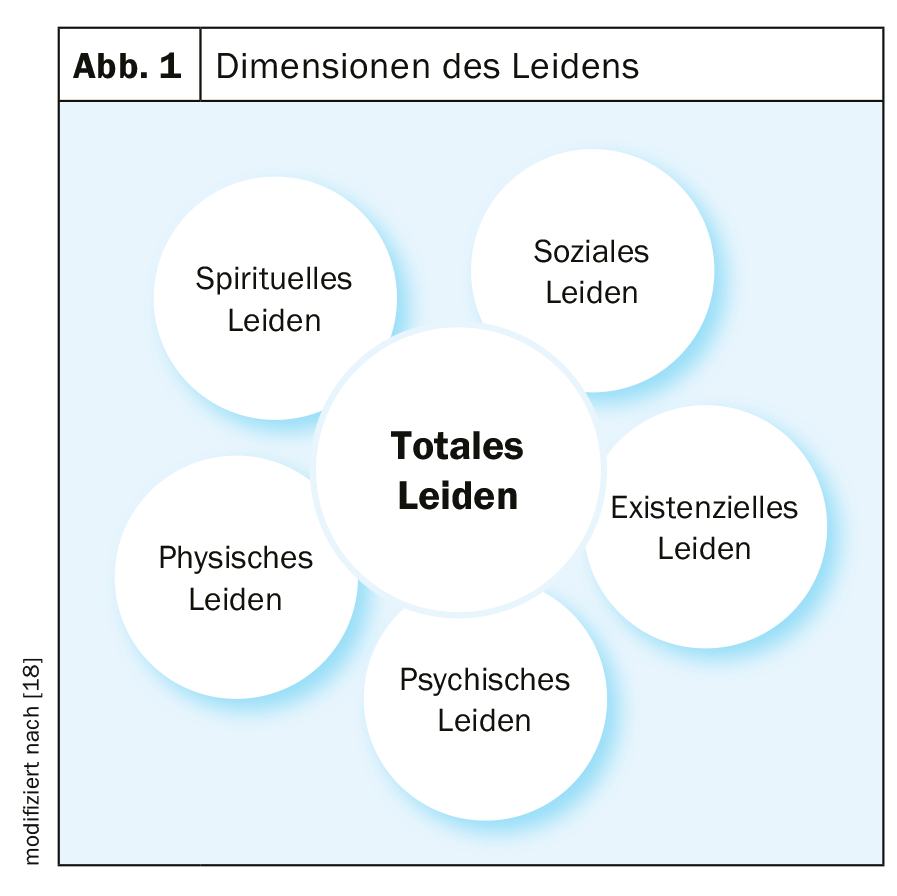

The main indication for PS is relief of “unbearable suffering.” However, this term is also not uniform or even defined in the literature [2]. In this context, ethical debates exist around the question of whether intolerable physical suffering should be equated with mental, social, or spiritual suffering (Fig. 1). Generally, the term “intolerable suffering refers to a symptom or condition mentioned by the patient that he/she does not want to endure.” The assessment of an intolerable condition is primarily the responsibility of the patient and is initially very subjective per se, but in some cases can also be made by loved ones or the treatment team [8].

Definition of “refractory symptom

Clear definition of a refractory symptom is central to the safe, effective, and ethical use of palliative sedation. A refractory symptom is one for which all possible attempts at therapy have failed or there is an assessment that no methods exist for relief within an acceptable time frame and harm-benefit ratio that the patient can tolerate [9]. A refractory symptom can be subjective and sometimes nonspecific. In pulmonology, in addition to malignant tumors, chronic diseases such as advanced COPD or pulmonary fibrosis are diseases that carry a high symptom burden. It is worth noting here that patients with non-malignant diseases not infrequently experience a high symptom burden over a longer disease period than cancer patients [10]. Breathlessness and anxiety are the symptoms that most often lead to palliative sedation, regardless of the underlying disease; at the same time, they are most common in pulmonary patients [11,12]. According to our clinical expertise, anxiety and shortness of breath are the symptoms that mostly require palliative sedation in a pulmonary clinic. However, persistent vomiting or hyperactive delirium are also symptoms that often require sedation in addition to symptomatic therapy. Pain is not an indication for palliative sedation per se, but is often mentioned in the context of refractory symptoms leading to palliative sedation. Patients who are primarily burdened by pain require adequate pain therapy (opiates, etc.); in some palliative patients, the administration of sedative medications is also necessary if symptoms such as agitation or anxiety exist in addition to the pain problem. Most patients requiring palliative sedation have more than one refractory symptom [13].

Not only physical symptoms can occur in the course of an incurable disease, but also psychological, spiritual or existential distress can be “refractory to therapy” and thus a reason for PS. Palliative sedation for psychological or existential suffering often leads to ethical conflicts or increased need for discussion among the treatment team when physical symptoms are not evident. The main reasons for this are a lack of standards for assessing and evaluating mental symptom burden. Before initiating palliative sedation for existential distress, other – treatable – causes must be ruled out (untreated depression, delirium, anxiety). Family conflicts can also put a lot of stress on a patient. Psychiatric co-assessment and case discussions within the treatment team, as well as ethics consultations when appropriate, can assist in decision making [14]. Different health care systems may have different rules for the sensitive issue of palliative sedation for mental or existential suffering.

Definitions of different types of sedation

Palliative sedation aims to reduce the perception of the symptoms causing the unbearable suffering. To achieve this, different types of sedation may be chosen or necessary. These differ in the depth of sedation and in their timing. The depth of sedation is differentiated between light sedation, in which the patient can still communicate verbally, and deep sedation, in which speech is no longer possible. Among the forms of PS differentiated by time course, intermittent sedation with administration of the drugs over a predefined period of time (e.g., only at night) is contrasted with continuous sedation with administration of the sedatives over an unspecified period of time and without interruption [15]. Intermittent sedation is often used as a form of “rest”, especially in cases of severe psychological stress or anxiety. Usually, intermittent sedation is started under the principle of “as light as possible, as deep as necessary.” The sedation protocols used should allow for individual dose adjustment (increase/decrease). Rarely, there is an indication for immediate continuous sedation right at the onset of PS. The reasons for this are mainly emergency situations at the end of life such as final hemorrhage. However, the combination of intolerable suffering and refractory symptoms with severely limited life expectancy (hours/few days) and the patient’s desire for relief may also be indications for immediate deep sedation.

Indication and decision making

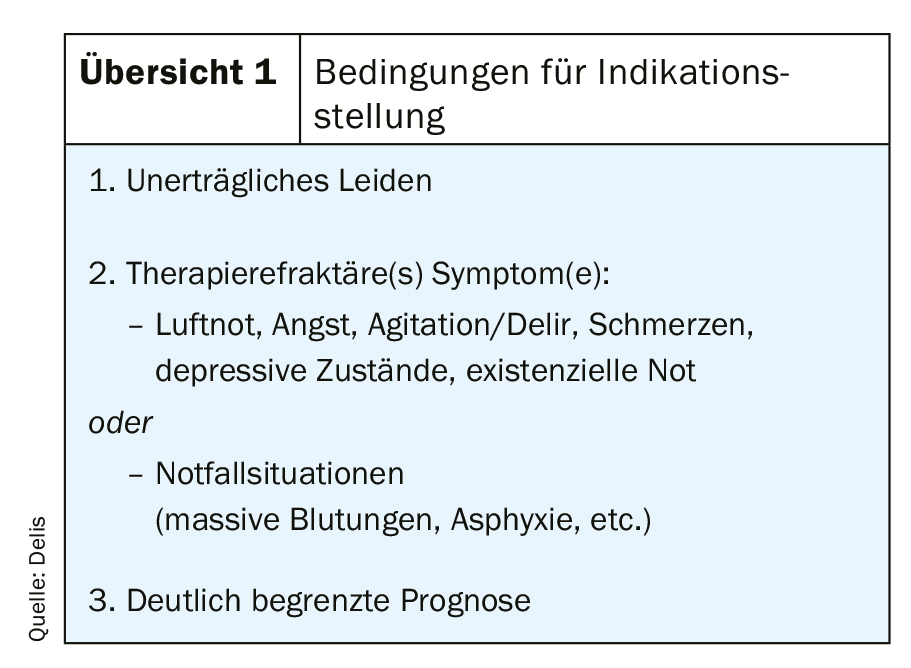

Various guidelines exist to assist in decision making regarding the initiation of palliative sedation. Although the definition and implementation recommendations differ in the various guidelines, there are basic conditions for the indication (overview 1). In addition to therapy-refractory symptoms in an incurable disease, they include the presence of the above-mentioned intolerable suffering. Existing guidelines do not provide a precise recommendation on whether intolerable distress alone is an indication, its relationship to other refractory symptoms, and whether treatment refractoryity relates to intolerable distress or other symptoms.

The decision for a specific form of palliative sedation should be made in close consultation with the patient and his or her loved ones. If possible, the indication should be established by an experienced palliative care team with a multiprofessional setup. Involvement of other care providers, such as the primary care physician or resident oncologist, can be helpful in difficult decision making [2,3].

Medication

The choice of an active ingredient depends largely on clinical preference as well as formal circumstances. In difficult cases, more than one drug may be needed to adequately sedate the patient. Medications designed to induce intermittent sedation may be administered orally, sublingually, rectally, intravenously, or subcutaneously. Subcutaneous or intravenous administration is required to maintain continuous sedation. The form of application should be chosen together with the patient if possible; previous positive experience with on-demand medication can be helpful in deciding on the form of application and type of active ingredient.

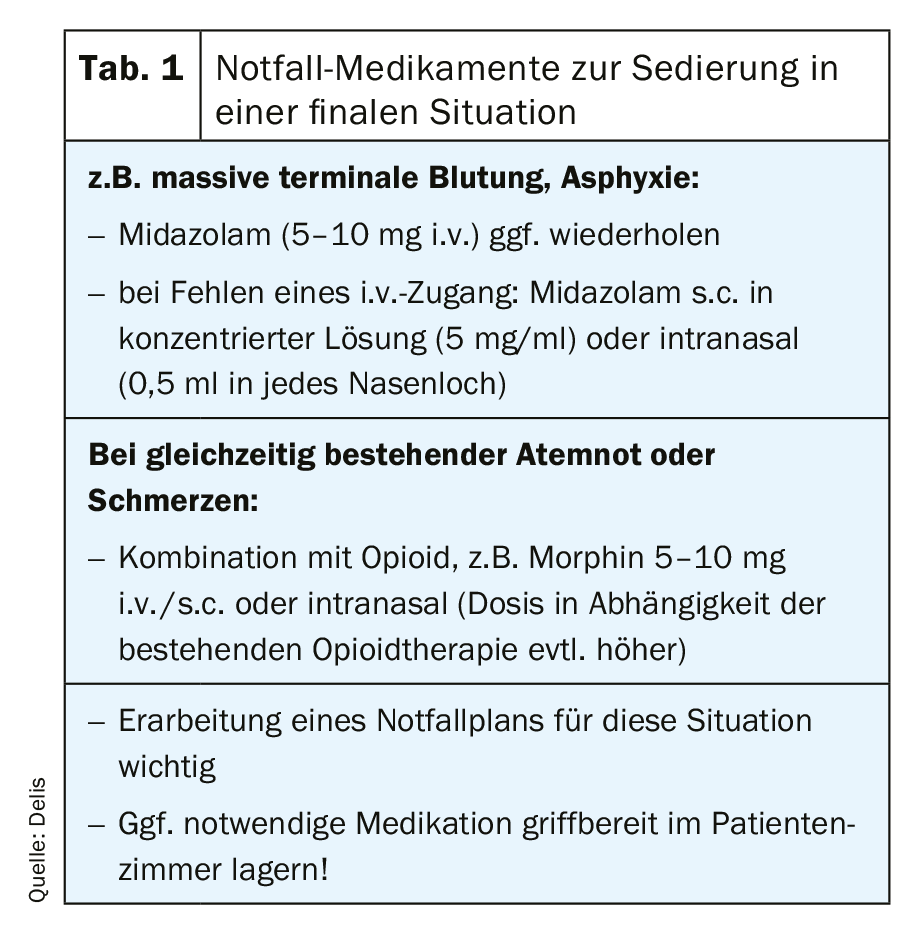

Agents of 1st choice for initiation of PS are benzodiazepines (especially midazolam). Typically, the initial dose is 0.5-1 mg/h i.v. or s.c., with on-demand doses of 1-5 mg. Often, the effective dose is reached at a run rate of 1-5 mg/h (EAPC-LL: up to 20 mg/h). In some cases of inadequate sedation, good symptom relief can be achieved by the additional administration of a neuroleptic with a sedative effect (frequently levomepromazine in Germany). If adequate sedation is not achieved with these measures, a switch should be made to narcotics such as propofol (initial dose 0.5 mg/kg/h, usual effective dose 0.5-2 mg/kg/h). Generally accepted guidelines or protocols exist regarding dose escalation of sedatives. However, the dose of sedative should be increased only if there is evidence of inadequate sedation [2,3]. For rapid initiation of sedation in emergency situations, Table 1 provides an overview.

In addition, opioid administration usually continues after palliative sedation is initiated. Opioids, however, are not suitable as “sedatives.” In the absence of pain and dyspnea, the indication for administration of morphine for refractory symptoms is not clear. In addition, the use of morphine may increase the risk of morphine-induced delirium [16].

Monitoring

There are no uniform recommendations regarding monitoring and documentation when palliative sedation is performed. The use of standardized protocols facilitates the survey of possible side effects of PS as well as the achieved relief of suffering (outcome parameters). Similarly, the depth of sedation as well as the frequency of elevation should be specified in such a protocol. Assistance in establishing such protocols may be provided, for example, by the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) or the RASS-PALL scale. In general, during the initiation phase of PS, sedation control is recommended at least every 20 minutes until adequate sedation is achieved and regularly thereafter, at least 3×/24 h [3,6].

Education and informed consent

The patient – or his legal representative – should be informed about the possibility of PS in an informative discussion with the attending physician. Especially in foreseeable emergency situations, it is important to discuss possible measures to alleviate discomfort in advance. of PS is relieving for patients, close relatives, but also for the treatment team. Here, it is helpful to explain the goals of PS based on the existing situation and the priority complaints. Likewise, the expected course without the use of PS can be estimated. The patient should be informed about the recommended sedation procedure, but also about the risks such as loss of consciousness, inability to communicate, etc. The continuation of existing medication and other care (e.g., parenteral nutrition, fluid substitution) should also be decided during this discussion. In the case of an emergency situation involving a dying patient who is incapable of giving consent and immediate action is required, consent may be waived [3,7].

Difference from killing

Palliative sedation differs from killing (on/without demand) in its primary goal. Palliative sedation has as its primary goal the alleviation of suffering; homicide has as its primary goal the hastening of death. Acceleration of death is not a primary or intended outcome of PS. Important distinguishing features are also the proportionality of the dose as well as the monitoring. For palliative sedation, the dose should be chosen only as high as necessary to relieve suffering. This can be done by documented repeated administrations or a titration with documentation of the effect. In a kill, high doses of a sedating substance are often administered in a single dose (no titration). For the most part, monitoring does not take place. In the case of palliative sedation, a faster death may possibly occur as an accepted “side effect”; the aim is to minimize suffering. In its “Reflections on Physician-Assisted Suicide,” the German Society for Palliative Medicine recommends that patients who wish to be assisted to die discuss, among other things, the options for palliative sedation [17].

Further studies are needed

Palliative sedation is an important option in a pulmonary clinic for symptom relief in the management of critically ill patients. The primary goal of palliative sedation in patients with incurable disease and specific refractory symptoms is to induce temporary or permanent light to deep sleep, but not intentionally death. Here, the clinician should be familiar with terms such as “intolerable suffering” or “refractory symptoms” to decide on the indication for PS. Collaboration among the patient, loved ones, treatment team, and palliative medicine expertise is recommended in determining indications and implementation. Shortness of breath, anxiety, persistent vomiting, and hyperactive delirium are the symptoms that most often require sedation. Most patients requiring palliative sedation have more than one refractory symptom. Midazolam is most commonly used for sedation; however, the combination of several sedatives may be necessary to achieve adequate relief of suffering. It is indispensable to have standard documentation, which includes regular monitoring of the patient’s condition and relief of suffering, in addition to the type and implementation of sedation and the leading symptom.

Unfortunately, the guideline used as a basis for this article shows little evidence regarding the definition of PS or its implementation. In general, very different concepts of PS exist worldwide, which require different ethical approaches. Therefore, further studies on the use of palliative sedation are warranted. Nevertheless, palliative sedation should be considered a valuable and effective measure for the treatment of end-of-life suffering.

Take-Home Messages

- Palliative sedation is an important treatment option for refractory symptoms and limited prognosis.

- Difficult indications should be discussed in a multiprofessional treatment team, if necessary with the help of an ethics consultation.

- When using palliative sedation, regular monitoring and documentation are essential.

Literature:

- Abarshi E, et al: BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017 Sep; 7(3): 223-229.

- Schildmann E, et al: Palliative sedation therapy: a systematic literature review and critical appraisal of available guidance on indication and decision making. J Palliat Med 2014; 17 (5): 601-611.

- Cherny N, et al: EAPC recommended framework for the use of sedation in Palliative Care. Pall Med. 2009; 23 (7): 581-559.

- www.hpna.org/position_PalliativeSedation.asp.

- Ziegler S, et al.: Continuous deep sedation until death in patients admitted to palliative care specialists and internists: a focus group study on conceptual understanding and administration in German-speaking Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2018; 22: 148.

- Schildmann E, et al: Medication and monitoring in palliative sedation therapy: A systematic review and quality assessment of published guidelines. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015; 49 (4): 734-746.

- Alt-Epping B, et al: Sedation in palliative care. Guideline for the use of sedative measures in palliative care. European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC). Pain 2010; 24: 342-354

- Bozzaro C, et al: “Suffering” in Palliative Sedation: Conceptual Analysis and Implications for Decision Making in Clinical Practice. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2018; 56: 288-294.

- Cherny NI, et al: Suffering in the advanced cancer patient: a definition and taxonomy. J Pall Care 1994; 10 (10): 57-70.

- Gore, et al: How well do we care for patients with end stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)? A comparison of palliative care and quality of life in COPD and lung cancer. Thorax 2000; 55: 1000-1006.

- Christensen V, et al: Differences in Symptom Burden Among Patients With Moderate, Severe, or Very Severe Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2016; 51 (5): 849.

- Raghu G, et al: An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 183: 788-824.

- Hasselaar JG, et al: Improving prescription in palliative sedation: compliance with Dutch guidelines. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167: 1166-1171.

- Bozzaro C: The concept of suffering in a medical context: an outline of problems using the example of deep palliative sedation at the end of life. Ethics Med 2015; 27: 93-106.

- Mahon M, et al: National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) Position Statement and Commentary on the Use of Palliative Sedation in Imminently Dying Terminally Ill Patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2010; 39 (5): 914-923.

- Reuzel RP, et al: Inappropiateness of using opioids for end-stage palliative sedation: a Dutch study. Palliat Med 2008; 22: 641-646.

- Materstvedt LJ: Intention, procedure, outcome and personhood in palliative sedation and euthanasia. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2012; 2(1): 9-11.

- Cassell EJ, et al: The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. 1991. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2019; 1(2): 6-9.