Urinary incontinence is one of the most common conditions in women. For example, the prevalence of urinary incontinence is 17% in women between 30 and 49 years of age, 23% between 60 and 79 years of age, and may exceed 50% in those over 80 years of age [1]. We speak of a disease when incontinence leads to hygienic and social problems. Incontinence is unsettling, affects the quality of life and can even lead to withdrawal from social life. Especially in the care of the elderly, it also causes high costs. The general practitioner already plays a key role in effective prophylaxis, but also in early detection of the disease and initiation of basic therapy, as well as in interdisciplinary cooperation with urogynecologists and incontinence specialists.

Fear of frequent urination often causes sufferers to reduce the amount they drink. The resulting dehydration can lead to dizziness, headaches, confusion, and even falls. The reduced drinking quantity leads to a reduction of the bladder capacity and to a stronger concentration of the urine, thus consecutively to irritable bladder symptoms.

Incontinence problems are still too rarely discussed; by patients out of shame, by doctors out of a certain helplessness. Different forms of urinary incontinence are addressed below.

Forms of urinary incontinence

The two most common forms of incontinence in women are stress incontinence (up to 50%) and hyperactive bladder/urge incontinence (20-30%), with mixed forms being common (20%). Rarer forms of incontinence are overflow incontinence, e.g., due to obstruction (prolapse, postoperative) or peripheral bladder denervation (<10%), reflex inc ontinence, e.g., due to multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, or Parkinson’s disease (<10%), and extraurethral incontinence, e .g., due to vesicovaginal fistulas.

In this article, we will focus on the two most common forms of incontinence seen in family practice – stress and urge incontinence and their mixed forms.

Stress incontinence: Leakage of urine during physical exertion – when coughing, sneezing, laughing, lifting weights or exercising – is called stress incontinence (formerly stress incontinence). In this form of urinary incontinence, there is a pelvic floor weakness resp. a too low urethral occlusion pressure compared to the intravesical pressure. Depending on the severity of the incontinence, urine is then lost in the form of drops, splashes or gushes.

The Ingelman-Sundberg grading commonly used in the literature is based on anamnestic criteria and divides stress incontinence into three degrees of severity:

- Grade I: urine leakage during coughing, sneezing and laughing

- Grade II: Urine leakage when lifting heavy loads, climbing stairs and walking

- Grade III: Urine leakage when standing, but not when lying down.

- For clinical routine, the classification according to Schüssler and Alloussi with cough test in case of filled bladder has proven to be effective:

- Grade I: dribbling when standing, no urine output or dribbling when lying down.

- Grade II: stream when standing, no urine output or dribbling when lying down.

- Grade III: gushing while standing and lying down.

The causes of muscle and connective tissue weakness are manifold. Childbirth, obesity, severe intra-abdominal pressure increases due to chronic coughing or constipation lead to an overload of the pelvic floor muscles. Lack of pelvic floor muscle training, tissue atrophy due to hormone deficiency, and age-related degenerative changes can also contribute.

Hyperactive bladder (urge incontinence, irritable bladder): Urge incontinence, on the other hand, is an uncontrolled loss of urine with an imperative urge to urinate.

Urge incontinence can occur as part of the syndrome of hyperactive bladder (OAB, “overactive bladder”). According to the ICS (International Continence Society), this is defined as a typical symptom complex of imperative urination, pollakiuria and nocturia, which can occur with urinary leakage (OAB “wet”) or without urinary leakage (OAB “dry”) [2].

Pathophysiologically, urge incontinence is usually due to overactivity of the detrusor. Detrusor overactivity, in turn, depends on several factors, but most often it is idiopathic. Other causes include eating and drinking habits, recurrent urinary tract and genital infections, genital hormone deficiency, and descensus conditions (cystocele). Bladder tumors, foreign bodies, interstitial cystitis (persistence of typical infection symptoms with aseptic urine), and metabolic diseases should be excluded. Urge incontinence can also be the initial symptom of a neurological disease such as multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease or the result of radiation therapy. Insufficient drinking, stimulant drinks, medications, excessive alcohol and nicotine use can promote hyperactive bladder.

Diagnosis of urinary incontinence

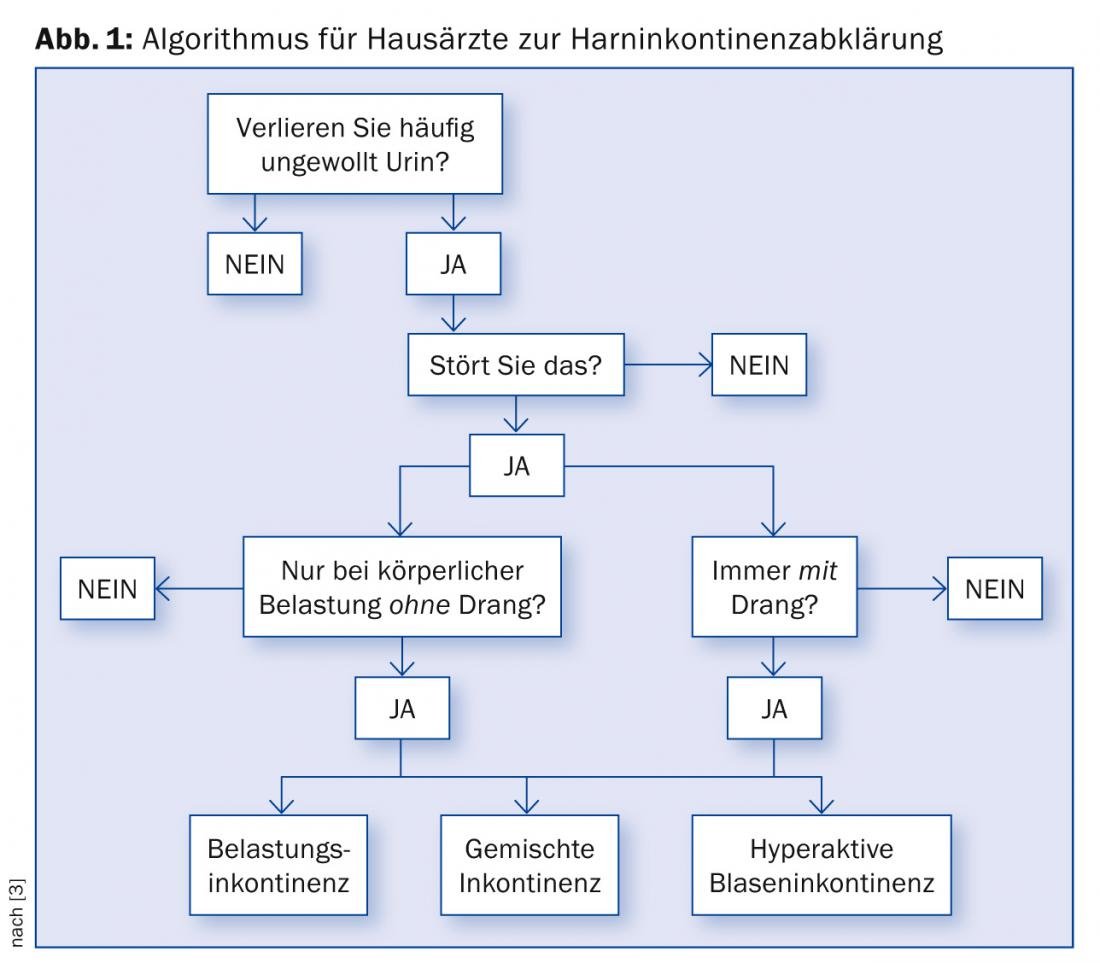

Basic diagnostics are already performed in the primary care physician’s office. With the medical history, the correct diagnosis can already be made in 70% and the effect of the disease on the quality of life can be recorded. The questions relate to micturition frequency, urge, incontinence during urge or coughing/sneezing/laughing, drinking quantity, nocturia, hematuria, dysuria, suffering pressure, medication (antidepressants), previous therapies/preoperative pelvic surgery, radiation therapy, and concomitant diseases. Figure 1 shows a corresponding algorithm [3]. Standardized questionnaires can also be helpful for objectification and progress monitoring.

A simple but important diagnostic tool is the drinking and micturition calendar (at www.blasenzentrum-frauenfeld.ch). This quickly gives us clear indications of the daily drinking quantity, micturition volumes and frequency of nocturia. For example, urge incontinence typically leads to frequent nocturia and thus disturbed sleep. It is also important to pay attention to nocturnal micturition volumes (50 or 500 ml). In this case, the primary care physician is offered the differential diagnosis of heart failure, which should then be further clarified and treated.

Urine stix and culture of midstream urine can be used to rule out urinary tract infection. Furthermore, abdominal ultrasonography can be used in the general practitioner’s office to determine residual urine or to detect renal ectasia and possibly a foreign body in the bladder.

Further diagnostic steps take place during a urogynecological examination . Genital atrophy, pelvic floor anatomy and the question of prolapse are elicited. Furthermore, the pelvic floor test assesses pelvic floor contraction and the cough test assesses urethral obstruction and the extent of stress incontinence with a full bladder.

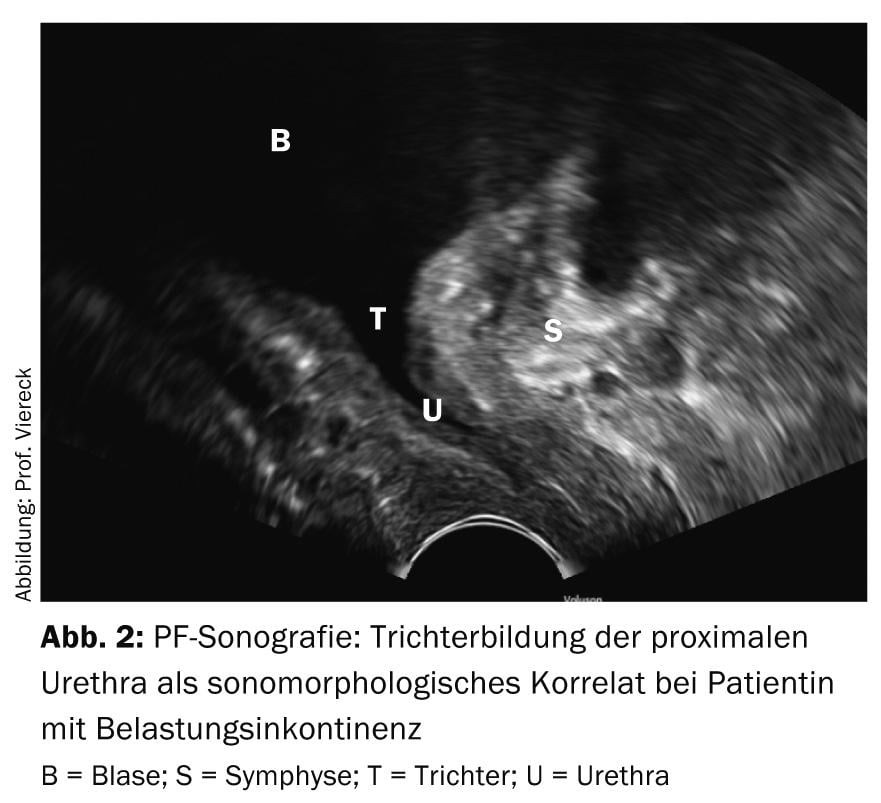

Pelvic floor ultrasonography is used to examine the entire lesser pelvis with the anterior, middle, and posterior compartments in two planes each at rest, during pushing/coughing, and under pelvic floor voluntary contraction [4]. Thus, the anatomy of the bladder, urethra, uterus, vagina, and rectum is visualized and assessed, e.g., whether the bladder neck funnels during squeezing (Fig. 2), whether descensus genitalis is present, and how high the residual urine volume is. For accurate planning of incontinence surgery, urethral length, urethral mobility, and paraurethral sulci height are relevant.

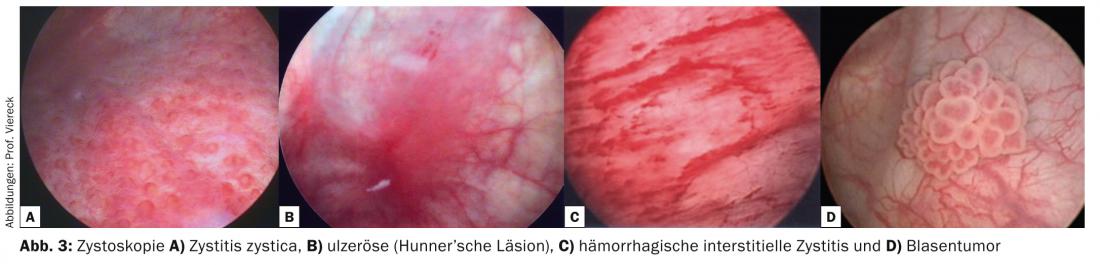

Swabs from the vagina and urethra can be used to rule out infections. Urethrocystoscopy provides information about residual urine, bladder capacity, and also bladder wall changes such as inflammation, chronic bladder wall infections (cystitis cystica) and barred bladder markings, pseudodiverticula, urothelial protective layer defects, interstitial cystitis with Hunner’s lesions, tumors, and bladder stones (Fig. 3) [5]. With this step-by-step diagnosis, the diagnosis is made and conservative therapy is initially initiated.

If the therapeutic success achieved is not satisfactory, surgical therapy is considered – if it is a recurrent situation, the next diagnostic step is urodynamics (step-by-step diagnostics). Urethrocystotonometry measures intravesical as well as intraurethral pressure simultaneously. Here, early first urge to urinate, decreased bladder capacity, deep compliance of the bladder, and occurrence of spontaneous or cough-induced detrusor contractions are among the indications of urge incontinence [6]. Urethrotonometry with deep urethral closure pressure and decrease or negativity of urethral closure pressure during coughing are indicative of stress incontinence. The measurement of urine flow – uroflow – enables the clarification of micturition disorders/stenoses. To determine the extent of incontinence, a pad test can be performed as an option to the cough test ( Fig. 4).

Therapy of stress incontinence

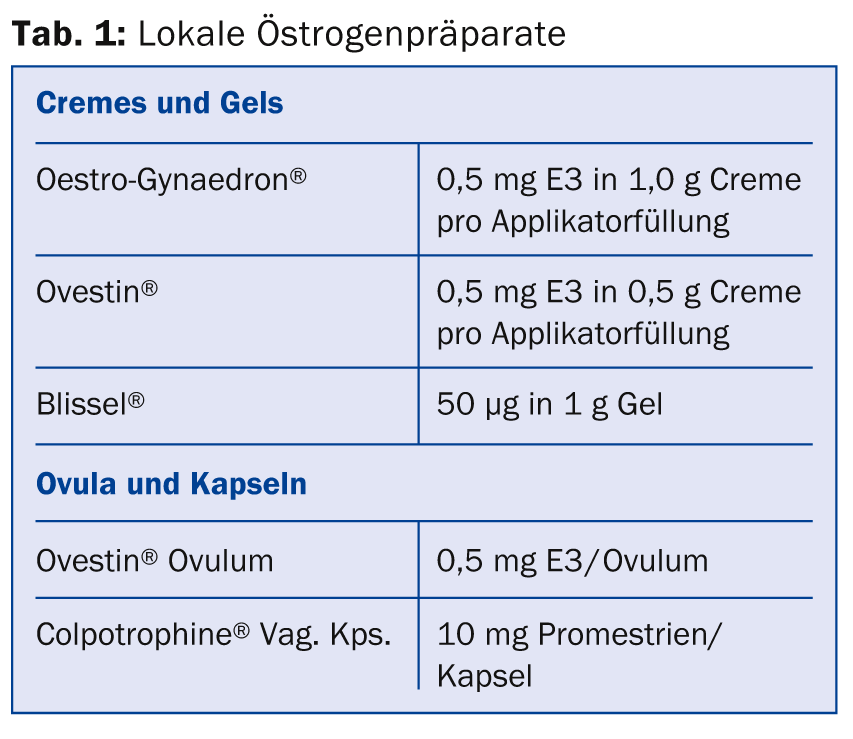

Both the German and English guidelines initially recommend conservative measures [7]. Depending on the BMI, these are weight reduction and local application of hormone preparations for epithelial proliferation (Tab. 1).

Physical therapy is supplemented with electrostimulation, biofeedback, or whole-body vibration therapy as appropriate [8]. This is to strengthen the pelvic floor muscles and optimize muscular coordination. Pessaries (cubes or rings made of silicone, disposable pessaries) serve as urethral restraints, are inserted together with an estrogen cream and are suitable for daily independent change by the patient (Fig. 5).

If these measures do not produce satisfactory improvement or healing after three months and the tissue is well built up with local estrogens, surgery is recommended. This has become much more individualized and differentiated as a result of developments in recent years.

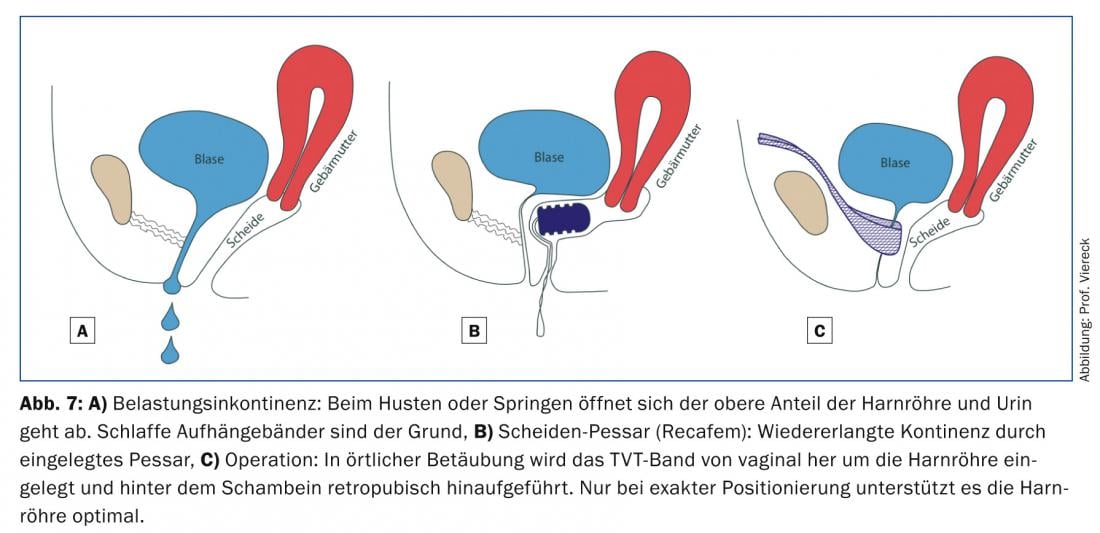

The goal of incontinence surgery is to restabilize the urethra through a less invasive procedure despite sagging suspensory ligaments and pelvic floor weakness. This is achieved by means of a sling operation (e.g. TVT band operation), which has largely replaced the previous colposuspension via abdominal incision. The polypropylene band (Fig. 6) is inserted retropubically (Fig. 7) under local anesthesia and analgesia.

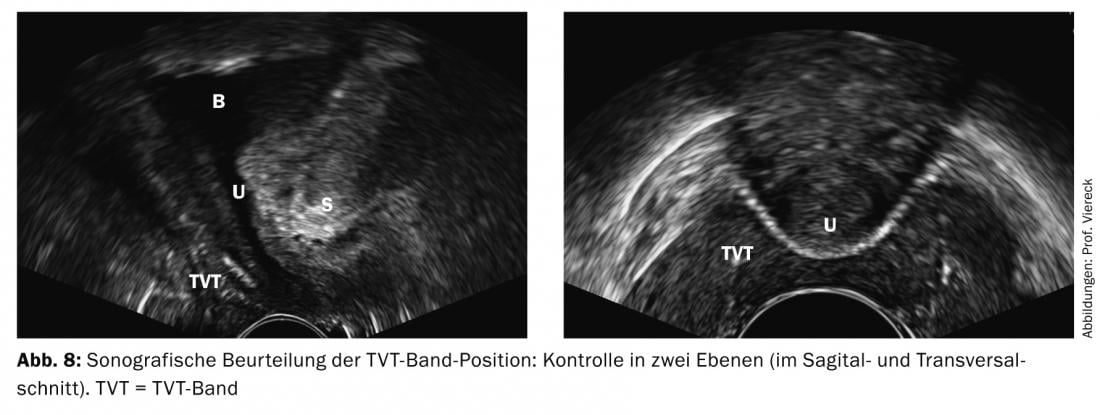

TVT stands for “Tension Free Vaginal Tape” – a tension-free synthetic tape that supports the urethra in the functionally relevant midsection. The TVT snare operation was developed by Professor U. Ulmsten from Sweden in the mid-1990s [9]. Other tapes with different insertion and fixation techniques have appeared on the market in recent years (TVT-O and TVT-Abbrevo tape with transobturator access and mini slings). Sonographic findings also allow very precise recommendations on surgical indications down to surgical details (Fig. 8). The preoperative sonographic assessment of urethral mobility and the level of the sulci paraurethrales is decisive for the surgical method. If the urethra is not very mobile and sulci are high, optimal results are more likely to be achieved with the retropubic TVT band. Due to their horizontal course, the transobturator loops have a low effect in a less mobile urethra and may arode into it from the inside at high sulci.

The latest figures in Switzerland therefore show a clear trend for the use of the classic retropubic TVT tapes – the old standard is becoming the new standard.

The insertion of a band is subject to strict criteria. If the tape is not lying correctly (dystop), it is important that the error is detected early and corrected [10]. PF ultrasonography proves to be essential especially in the so-called “failures of the method” or postoperative complications. The most common postoperative complications include, in addition to persistent stress incontinence (surgical failure), obstructive voiding symptoms, residual urine formation with/without recurrent urinary tract infections, and de novo urge incontinence.

The recovery time after this surgery is short and the surgical scars are minimal. Long-term data show that the objective cure rate is 83 and subjective satisfaction is a high 95% [11]. Today’s modern surgical procedures are less invasive and yet very successful, which is a great advantage.

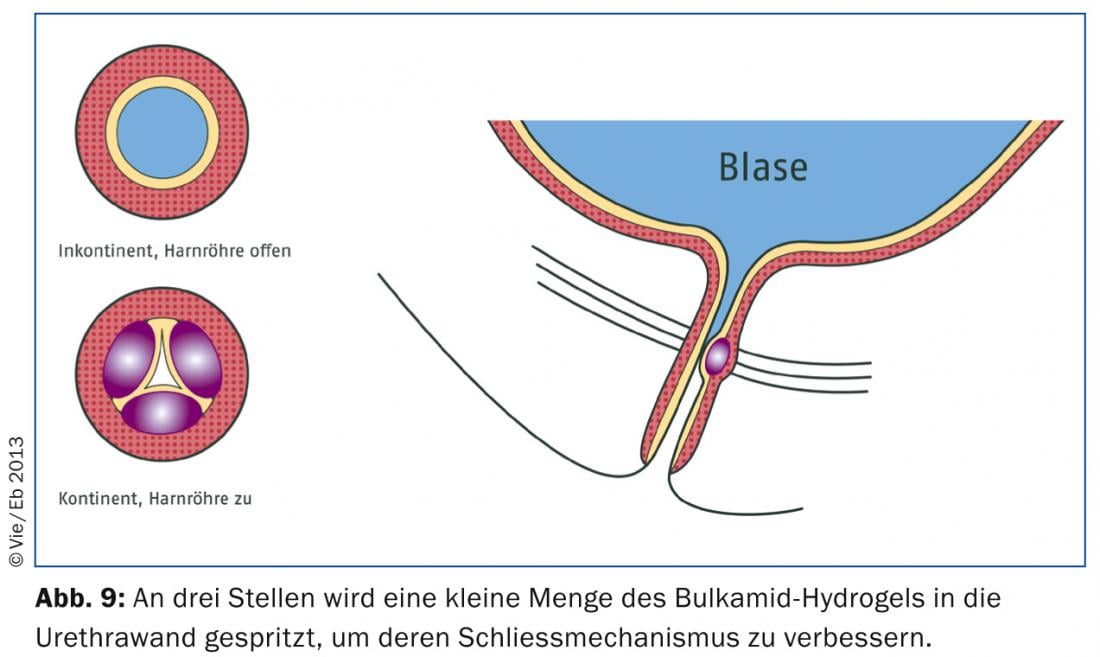

A surgical treatment alternative for stress incontinence is periurethral injection with bulking agents (Bulkamid) . It is used in therapy failures after colposuspension, band insertions with immobile urethra and in the very elderly woman. Injection around the urethra is usually performed under local anesthesia only, making it the least invasive incontinence technique. A small depot of Bulkamid hydrogel is injected into the urethral wall at three points (Fig. 9) . This constricts the urethra (coaptation). Due to lack of long-term data, there is no consistent recommendation for primary therapy to date.

Therapy of urge incontinence

The conservative measures for urge incontinence are good drinking amounts, few stimulant drinks such as coffee, bladder training (by suppressing urge episodes and gradually lengthening micturition intervals), phytotherapy with cranberry juice, gentle intimate care, and comprehensive infection prophylaxis and sanitation. Because a variety of medications can trigger hyperactive bladder, the primary care physician should review the side effect list of medications taken. Furthermore, constipation should be treated and the patient should be supported in stopping smoking, for example.

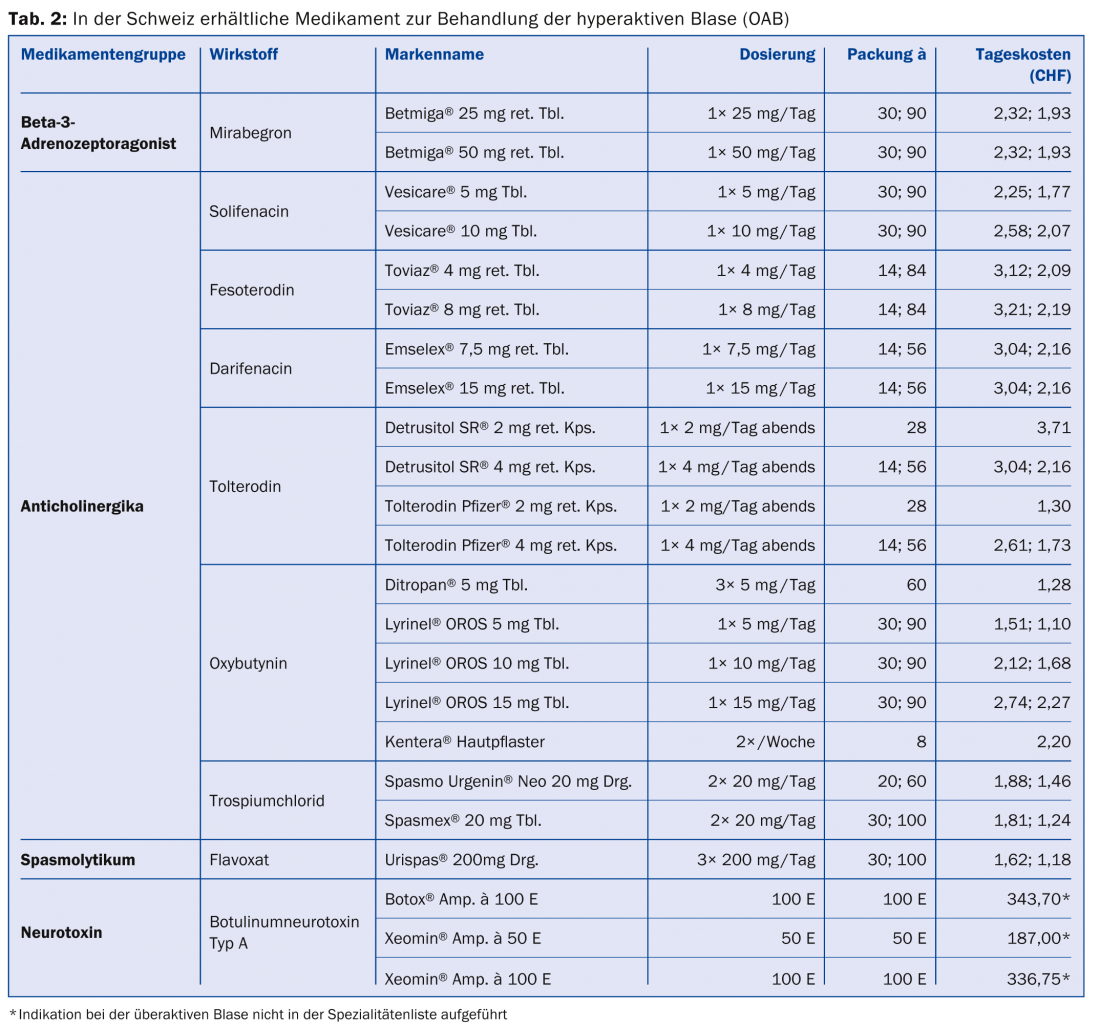

Local estrogenization as well as pelvic floor training with relaxing electrostimulation or Galileo vibration training are important aspects of treatment. Bladder relaxation with medication (Table 2) supports primary therapy.

The drugs have anticholinergic and thus detrusor-relaxing effects. They reduce incontinence and urge episodes as well as micturition frequency and increase micturition volume. Possible side effects include dry mouth, constipation, or visual disturbances. In the elderly, cognitive performance may be impaired. Contraindications to anticholinergics are narrow-angle glaucoma and tachyarrhythmia.

Recently, there has also been another drug therapy approach. The active ingredient mirabegron (Betmiga®) is a beta-3-adrenoceptor agonist and has been available in Switzerland since August 15, 2014. It is the first representative of a new class of substances with a novel mechanism of action in 30 years. Data to date show very good efficacy and few, especially no, anti-cholinergic side effects [12].

If the desired effect fails to appear, instillation therapy with intravesical application of anti-inflammatory and bladder-relaxing drugs is performed.

As a last step in therapy-resistant invalidating urge incontinence without residual urine formation, botulinum toxin A can be injected into the bladder trabeculae. Side effects are usually mild, but occasionally there may be temporary residual urine formation and even urinary retention.

Since genital descensus leads to urge incontinence in 29.8% of affected individuals, the descent must be addressed surgically after unsuccessful conservative therapy. However, stretching of the vagina and elevation of the bladder floor may result in delarious stress incontinence postoperatively. In this case, we recommend the insertion of a TVT band on both sides.

Sacral neuromodulation should also be mentioned as an ultima ratio after failure of classical therapy concepts for bladder dysfunction and chronic pelvic pain syndrome. A reduction in urge and incontinence symptoms is achieved by stimulating the sacral nerves with weak electrical impulses.

Therapy of mixed urinary incontinence

In women with mixed stress and urge incontinence, it is important to filter out the dominant symptoms and then address them primarily conservatively or surgically.

Overall, it must be said that a multimodal therapy-prophylaxis concept is the best way to reach the goal [13,14]. With well-coordinated individual treatment and support for the patient, incontinence problems can usually be cured or significantly alleviated. This spares those affected a great deal of suffering and shame. Quality of life and social integration are improved, care is facilitated and, last but not least, healthcare costs are reduced.

Irena Zivanovic, M.D.

Literature:

- Nygaard I, et al: Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. Pelvic Floor Disorders Network, JAMA 2008; 300(11): 1311.

- Haylen BT, et al: An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourology and Urodynamics 2010; 29: 4-20.

- Schuessler B: How can pelvic floor problems be meaningfully integrated into family practice? Therapeutic Review 2010; 7-9.

- Kociszewski J, Viereck V: Stress incontinence – individual treatment thanks to optimal diagnosis. Urol Urogynecol 2010; 17(3).

- Viereck V, Kociszewski J, Eberhard J: Preoperative urogynecologic diagnosis. Urol Urogynecol 2010; 17(4).

- Schär G, Sarlos D: Urinary incontinence in women – pathophysiology and diagnostics. Therapeutic Review 2003; 60: 249-256.

- Reisenauer C, et al: Interdisciplinary S2e guideline diagnosis and therapy of stress incontinence in women. Geburtsh Frauenheilk 2013; 73.

- Von der Heide S, Viereck V: Vibration therapy. In: Carrière, B, Brown C (eds.): Pelvic floor, physiotherapy and training. Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2012 (2nd, updated and expanded ed.).

- Ulmsten U, et al: An ambulatory surgical procedure under local anesthesia for treatment of female urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J 1996; 7: 81-86.

- Viereck V, Eberhard J: Incontinence surgery – indications, choice of surgical method, surgical technique, management of early and late complications. J Urol Urogynecol 2008; 15(3).

- Kociszewski J, et al: Tape functionality: Sonographic tape characteristics and outcome after TVT incontinence surgery. Neurourol Urodyn 2008; 27: 485-490.

- Khullar V, et al: Efficacy and tolerability of mirabegron, a β(3)-adrenoceptor agonist, in patients with overactive bladder: results from a randomised European-Australian phase 3 trial. Eur Urol. 2013 Feb; 63(2): 283-295.

- Viereck V: Urogynecologic problems in the senior to the very old. info@gynecology 2012; 2.

- Eberhard J, Viereck V: Simple diagnostics – multimodal conservative therapy. Family Practice 2008; 7: 9-14.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- Urinary incontinence, bladder and intimate discomfort are among the most common women’s conditions. They can occur at any age and almost always have multiple causes.

- A basic diagnostic consists of a focused history, exclusion of infection, residual urine determination, and keeping a drinking-micturition calendar.

- Successful therapies of urogynecological diseases are based on multimodal stepwise concepts, which are individually tailored to the patients.

- In case of failure of basic therapy, complex complaints in the context of urinary incontinence and before surgical therapy, referral of patients to a urogynecological center is required.

- The success of surgery is favorably influenced by adequate tissue preparation, careful diagnostics, optimal selection of the surgical method, and good postoperative follow-up. Continued conservative measures such as drink training and local hormone application serve as long-term prophylaxis.

A RETENIR

- L’incontinence urinaire, les douleurs vésicales et intimes font partie des maladies gynécologiques les plus fréquentes. Elles peuvent survenir à tout âge et ont presque toujours des causes multiples.

- Un diagnostic de base repose sur une anamnèse ciblée, une exclusion d’une infection, une détermination des urines résiduelles et la mise en place d’un calendrier mictionnel.

- La réussite des traitements des maladies uro-gynécologiques repose sur des concepts de traitement progressifs multimodaux qui sont adaptés individuellement aux patientes.

- En cas d’échec du traitement de base, des symptômes complexes dans le cadre de l’incontinence urinaire et avant une intervention surgicale, il est indispensable d’adresser les patientes à un centre d’uro-gynécologie.

- The success of the operation is favorably influenced by adequate preparation of the tissues, quick diagnosis, optimal choice of surgical technique and adapted post-operative care. Des mesures conservatoires durables telles que l’entraînement à boire et une hormonothérapie locale servent à la prophylaxie à long terme.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(11): 24-32