The overall number of strokes induced by a patent foramen ovale is small. It is somewhat higher, although still moderate, in cryptogenic ischemic insults. Does a PFO closure help?

Between 20 and 25% of the healthy population has a patent foramen ovale (PFO), although it is symptomatic in only 2%. Although the overall number of strokes caused by PFO is small, younger stroke patients in particular (<55 years) have an increased risk of cryptogenic ischemic insult in the presence of a PFO. PFO-triggered strokes are thought to be caused by paradoxical emboli. In the process, thrombi pass from the venous to the arterial vascular system. The diagnosis is made according to the principle of exclusion. Transesophageal echocardiography is used as an imaging procedure in cases of suspicion.

Harmless or pathogenic?

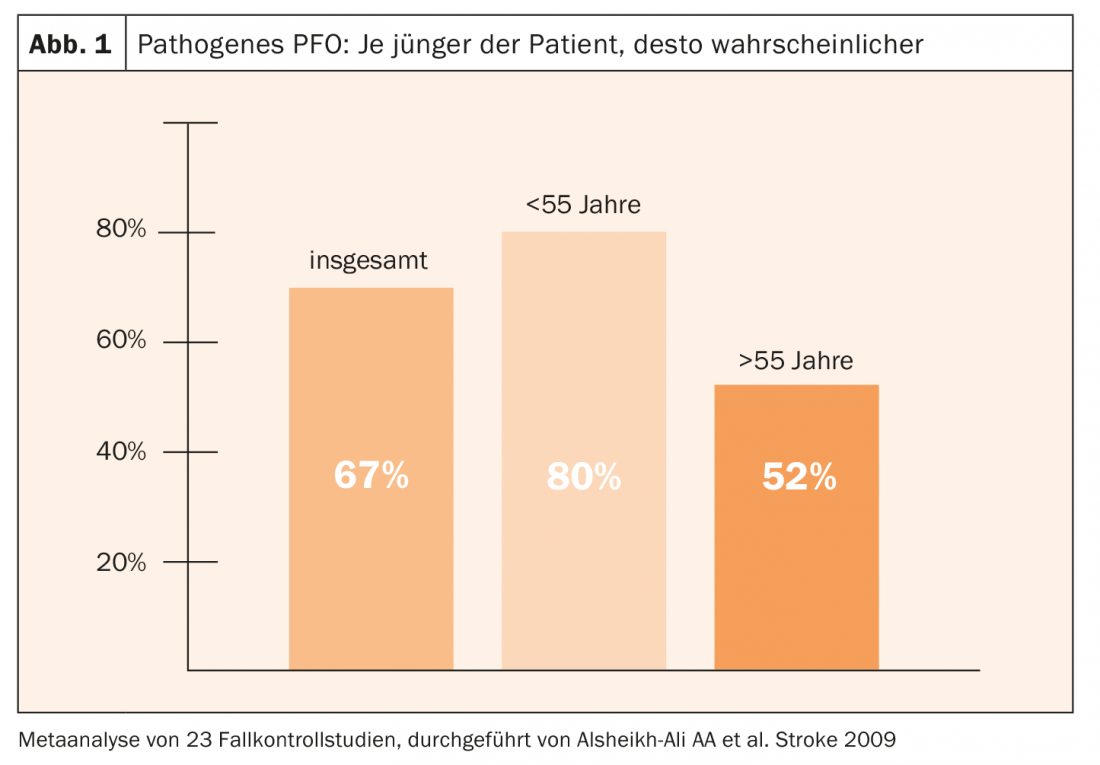

According to a metastudy, the probability of a pathogenic PFO is on average 67% of all PFO sufferers. Younger patients are at higher risk than older patients (Fig. 1) . Characteristic of a pathogenic PFO are an increased right-to-left shunt and an atrial septal aneurysm. Low cardiovascular risk factors combined with younger age also suggest a pathogenic PFO. Clinical clues may also arise from context, such as circumstances suggestive of paradoxical embolism: neurologic symptoms on awakening, migraine, phlebothrombosis or pulmonary embolism, sleep apnea, or preceding Valsalva maneuver. Because of this difficult diagnosis, which is like looking for a needle in a haystack, close cooperation between the neurologist and the cardiologist is central.

Risk of recurrence

In general, the risk of recurrence in stroke patients with PFO varies greatly among individuals and is therefore difficult to predict. Factors favoring recurrence of stroke include older age, septal aneurysm, use of aspirin instead of oral anticoagulants, coagulation disorders, and diameter of the PFO.

Stroke patients with PFO can currently be treated with platelet function inhibitors (TFH), anticoagulation, or PFO closure, although closure does not preclude long-term medical management. But which path is best – and for whom?

Umbrella!

Whether interventional occluder closure reduces the risk of recurrence in stroke patients with PFO compared with medical therapy alone has been the subject of numerous studies.

Three older RCTs-CLOSURE-I (2012), PC-Trial (2013), and RESPECT (2013)-showed no benefit of occluder closure with respect to their primary endpoints and over a relatively short follow-up period. However, the intervention arm had a lower event rate than the drug-treated control group in each case. In the per-protocol analysis of the RESPECT trial, event reduction was significant in the intervention group.

Meanwhile, three recent studies have demonstrated the efficacy of occluder closure with respect to recurrence risk in patients (<60 years) with cryptogenic stroke. “Match-decisive” factors were the longer follow-up, the inclusion of high-risk PFOs (large shunt volume, atrial septal aneurysm), the exclusion of patients with transient ischemic attacks and lacunar cerebral infarction, a lower burden of cardiovascular risk factors, and the use of second-generation devices (“double disk devices”).

The three-arm CLOSE trial (2017) evaluated the treatment effect of PFO closure vs anticoagulation vs treatment with TFH in patients (16-60 years) with PFO and cryptogenic stroke. In a 1:1:1 ratio, 663 patients were randomized into three groups and treated with either PFO closure + TFH, TFH as monotherapy, or oral anticoagulation. The primary end point was stroke. During the observation period of 5.3 years, no stroke occurred in the occluder group, but 14 cases occurred in the TFH group (HR 0.03; 95% CI 0-0.26; p=0.001). In the comparison of anticoagulation vs TFH, there were three vs seven strokes. Thus, there were no significant differences between anticoagulation and TFH therapy, whereas occluder therapy proved superior overall.

REDUCE (2018) compared the treatment success of PFO closure + TFH with TFH therapy alone over an observation period of 3.2 years in 664 patients. Repeat ischemic insults occurred in 6/441 patients in the Occluder group versus 12/223 patients in the TFH group, corresponding to a HR of 0.23 (95% CI 0.09-0.62; p=0.002). New silent infarcts were about equally frequent in both groups.

DEFENSE-PFO (2018, n=60) also indicated the benefit of an occluder: The primary endpoint was met at two-year follow-up in six patients in the drug arm but did not occur in the intervention group. The long-term results of the RESPECT study, whose results were published in 2017 after an observation period of six years, also give cause for optimism.

All results taken together show a relative reduction in stroke recurrence rate of about 75% when PFO closure is performed. However, this only affects patients who are under sixty years of age and have a moderate to large right-to-left shunt. The extent to which patients >60 also benefit from closure remains unclear due to a lack of data.

At the interface between neurology and cardiology

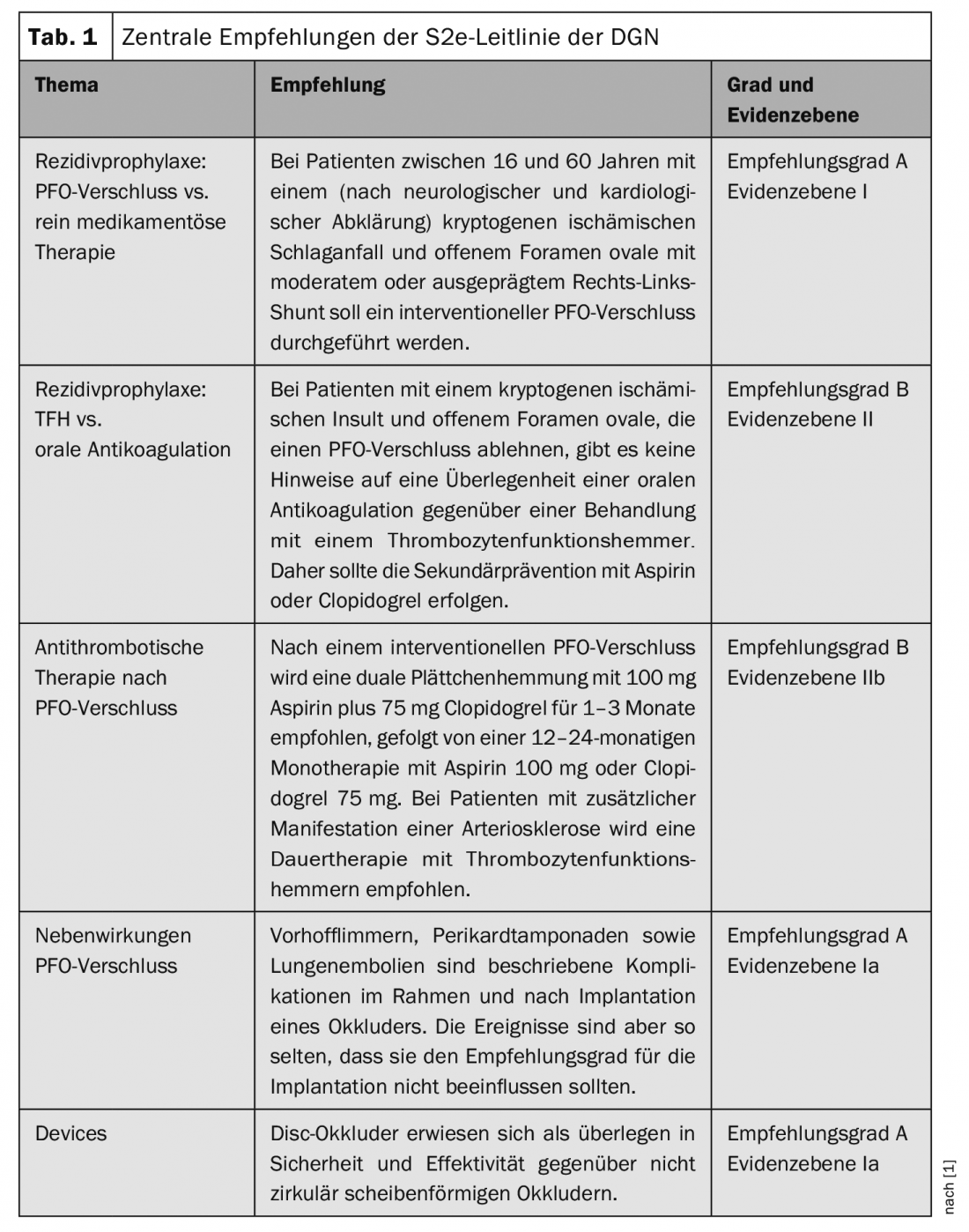

Based on these findings, the German Society of Neurology (DGN), the German Stroke Society (DSG), and the German Society of Cardiology (DGK) have developed a new guideline [1]. It is aimed at both neurologists and cardiologists. The main recommendations are summarized in Table 1.

Side effects

The occluder process is considered safe. Complications during surgery occur in 2.6% of cases, and long-term mortality or risk of cardiac surgery is <0.1%. The most common late complication is device thrombosis (1-2%). Atrial arrhythmias occur in 0.5-15%, mostly during the first 45 days after surgery (self-limiting). Dangerous, but with 0.5-1% not frequent, are pericardial effusions and cardiac tamponade. In about 10-15%, the shunt remains. In this regard, the AMPLATZER® occluder (PC-Trial, RESPECT, DEFENSE-PRO) delivered the best results in studies. GORE® HELEX (REDUCE) and GORE® CARDIOFORM (REDUCE) are also recommended.

Currently, there are no studies that focus on postoperative management. However, according to the available data, dual TFH therapy is recommended for 1-6 months after closure. Simple TFH treatment should continue for a period of five years to minimize the risk for device thrombosis. Furthermore, if an invasive procedure is planned within the first six months after PFO closure, antibiotic prophylaxis should be considered.

Literature:

- Diener HC, et al: Cryptogenic stroke and patent foramen ovale. S2e guideline, 2018. In German Society of Neurology, ed: Guidelines for Diagnostics and Therapy in Neurology. www.dgn.org/leitlinien, last accessed March 12, 2019.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2019; 17(2): 32-34.