The treatment strategy is determined according to the patient’s age and general condition. Younger fit patients receive intensive treatment with induction therapy (at least four cycles), followed by high-dose chemotherapy/autologous stem cell transplantation (early planning!) and, if necessary, short consolidation or longer maintenance therapy. Older patients receive combination treatment including a new agent over a period of 12-18 months. In the case of recurrence, new substances can be used. In young patients, repeat autologous or, in selected cases, allogeneic stem cell transplantation may be discussed. Patients must be monitored for drug side effects and therapy must be adjusted in a timely manner.

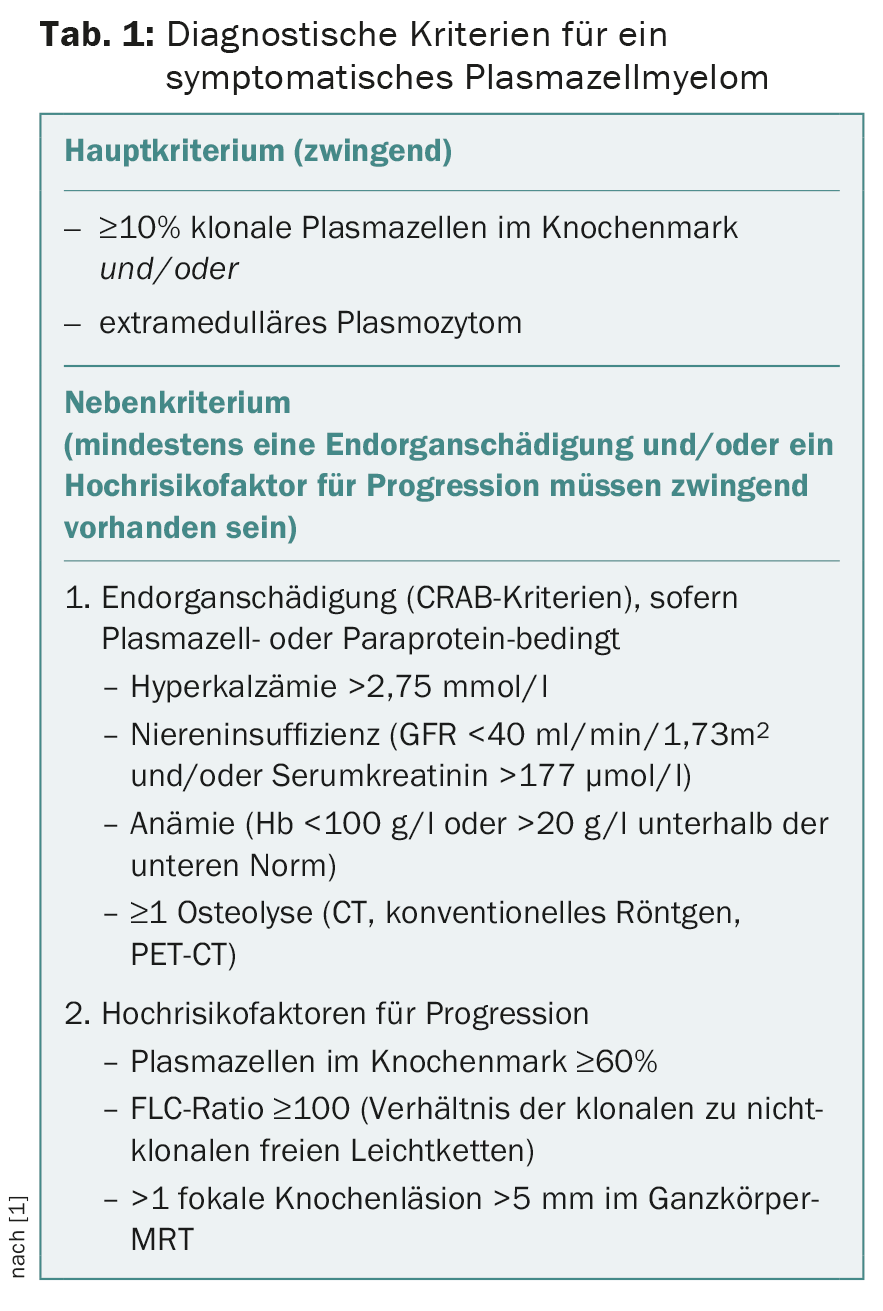

The International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) recommendations for the diagnosis of plasma cell disease were adapted last year [1].

Patients with previously asymptomatic high-risk plasma cell myeloma (progression to a symptomatic stage within less than two years very likely) are now considered to require therapy (Tab. 1).

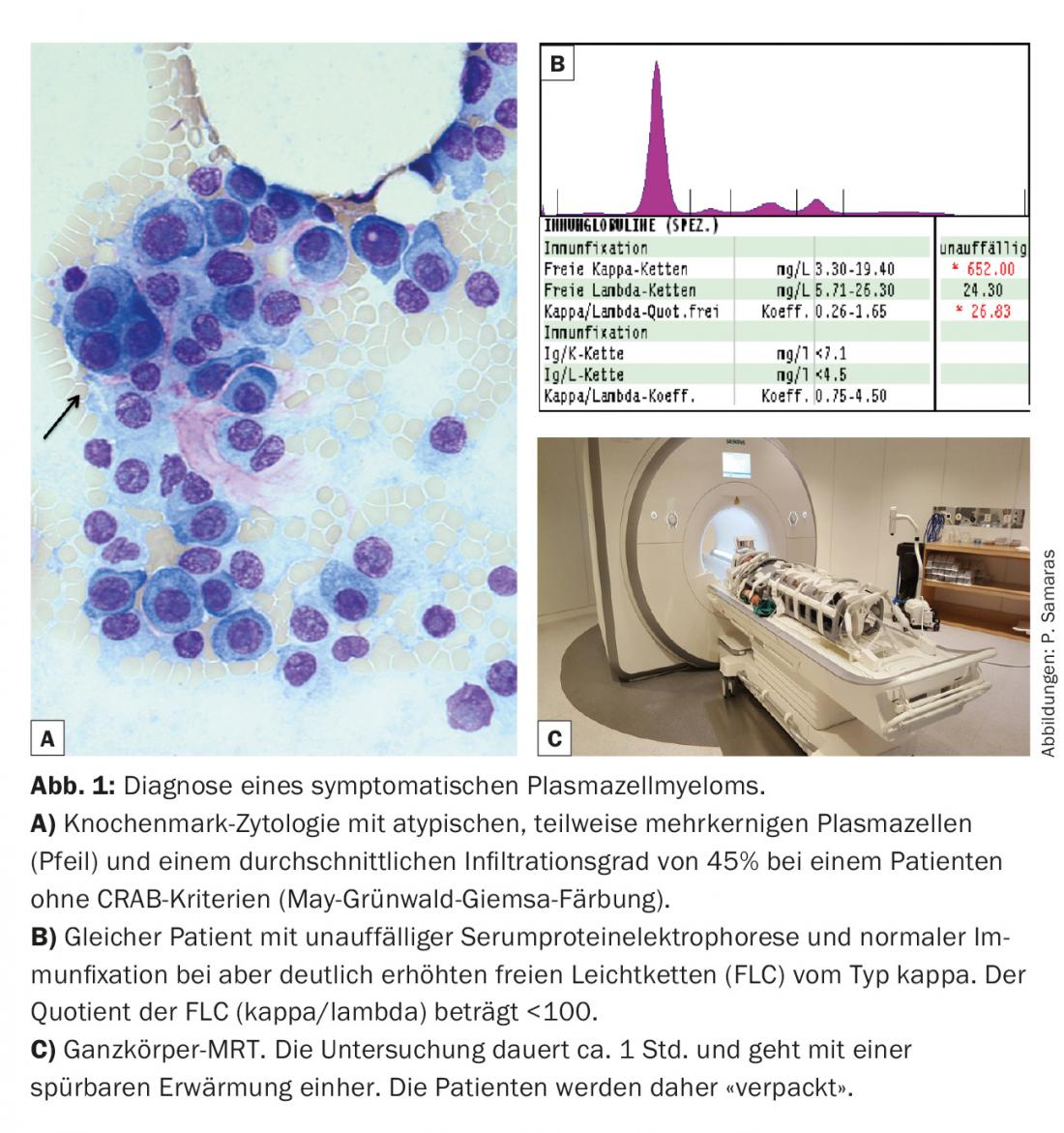

In practice, this means, among other things, that for patients without end-organ damage (CRAB criteria) but with 10-60% plasma cells and a light-chain quotient of <100, whole-body MRI is recommended (Fig. 1). It is worthwhile to ask the local radiology department if this examination is possible. As can be seen from the figure, patients must be appropriately prepared for the examination.

The diagnostic value of the free light chain (FLC) concentration in serum has also been strengthened (Tab. 1). In studies to date, FLC have been measured exclusively using the FreeliteTM test (The Binding Site). Regarding the CRAB criteria, renal function impairment was supplemented by the specification of a minimum creatinine clearance. Formally, only renal function impairment due to cast nephropathy is myeloma-defining, but renal function impairment due to, for example, AL amyloidosis or light chain deposition disease (LCDD) is not.

CT and PET-CT were newly added as possible diagnostic tools for the clarification of osteolysis. CT is currently the method of choice as a screening method for osteolysis.

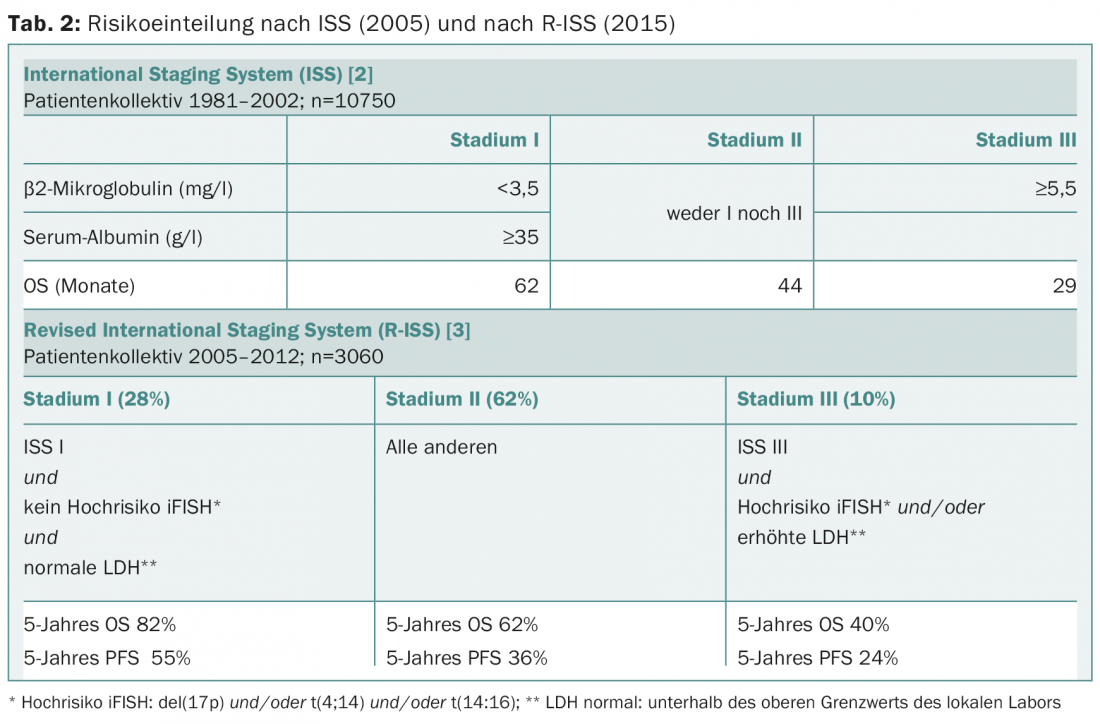

Risk stratification was also adjusted this year as treatment response has improved since the ISS score was published ten years ago [2]. The revised ISS score (R-ISS) now additionally incorporates iFISH analysis and LDH elevation (Table 2) [3]. The R-ISS is applicable to all patients, including the elderly (>65 years) and those not receiving high-dose chemotherapy. The R-ISS has not yet been validated in an additional patient population, and the median follow-up was just under four years.

Frailty is an important factor in assessing treatment capability, adjustment, and prognosis. In clinical practice, we usually use our clinical experience to estimate frailty, but it can also be assessed systematically, e.g., analogous to the IMW recommendation, using an online tool (www.myelomafrailtyscorecalculator.net) [4]. There are also recommendations for therapy management according to fitness, although this approach is expert-based and has not yet been prospectively studied in trials [5].

Further important information on prognosis is obtained only in the course of therapy. For example, achieving a complete response in patients of any age is associated with improved overall survival and progression-free survival.

First-line treatment with autologous stem cell transplantation.

If there is an indication for therapy, the first step is to clarify whether intensive treatment with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation (HDCT/ASZT) is an option for the patient.

Patients who qualify for this intensive therapy strategy are younger than 65-75 years and have no serious comorbidities. In addition to age, various clinically oriented comorbidity scores can be consulted to assess transplant eligibility. Therapy usually consists of a minimum of four to a maximum of six cycles of induction treatment followed by HDCT/ASZT and, depending on response, subsequent shorter consolidation and/or longer maintenance therapy.

The induction was to contain the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib and consist of a total of three compounds. Common combinations in Europe are bortezomib/cyclophosphamide/dexamethasone (VCD) or bortezomib/thalidomide/dexamethasone (VTD), and in the United States bortezomib/lenalidomide/dexamethasone (VRD). If there are contraindications to the use of bortezomib, lenalidomide, a 2nd generation immunomodulator (IMiD) and a further development of thalidomide, can be used instead, also in combination with dexamethasone (Rd) and possibly additionally cyclophosphamide as a third substance (RCD). Since lenalidomide is not yet approved for first-line therapy in Switzerland, the patient must first apply for reimbursement by the health insurance company. Early contact with the transplant center immediately before or shortly after initiation of induction treatment is important to plan stem cell collection and transplantation in a timely manner.

HDCT/ASCT has been considered standard therapy for fit, younger patients since the 1990s [6]. The alkylating substance melphalan is administered at a dose of 200 mg/m2 (MEL200). In patients over 65 years of age and/or with physical limitations such as renal impairment, the dose is usually reduced to 100 or 140 mg/m2 (MEL100 or MEL140). Since treatment nowadays is primarily based on biological rather than calendar age, fit patients aged 65-70 years can still receive full doses of MEL200, provided there are no physical limitations. In case of insufficient response after HDCT/ASCT or in patients with a very unfavorable cytogenetic risk profile (t(4;14), t(14;16) or del(17p), another HDCT/ASCT with melphalan can be performed in the sense of a so-called tandem transplantation at an interval of three months, provided that the first one was well tolerated by the patient.

In patients who have not achieved a complete response after HDCT/ASZT, two additional cycles of therapy may be administered as consolidation therapy. Here, the same drug combination is usually used as already for induction, but the use of a new substance class is also possible. The indication for maintenance therapy with a proteasome inhibitor or an IMiD for several years or until progression must be made on an individual basis. Due to the aggressiveness of the disease, patients with high-risk cytogenetics certainly qualify. Currently, the efficacy of a third-generation oral preoteasome inhibitor, ixazomib, as maintenance therapy after ASZT is being tested in a large international study in which the University Hospital Zurich is also participating (https://clinicaltrials.gov: NCT02181413).

First-line treatment without stem cell transplantation

In elderly patients who are not eligible for HDCT/ASCT, bortezomib- or lenalidomide-based therapy with two- or three-drug combination should be used. Common drug combinations include bortezomib/melphalan/prednisone (VMP), lenalidomide/dexamethasone (Rd), and bortezomib/dexamethasone (Vd). The duration of therapy is crucial for a deep and thus long-lasting response. It should be maintained for a period of 12 (VMP) to at least 18 (Rd) months. Particularly close attention must be paid to therapy-limiting side effects such as polyneuropathy or fatigue, so that the drug dose can be adjusted in time or the treatment paused as needed. In general, bortezomib should be applied only once weekly and subcutaneously, and the dose of dexamethasone should be limited to max. 40 mg per week can be reduced. In this way, early discontinuation of therapy can be avoided, thereby also increasing treatment efficiency [7].

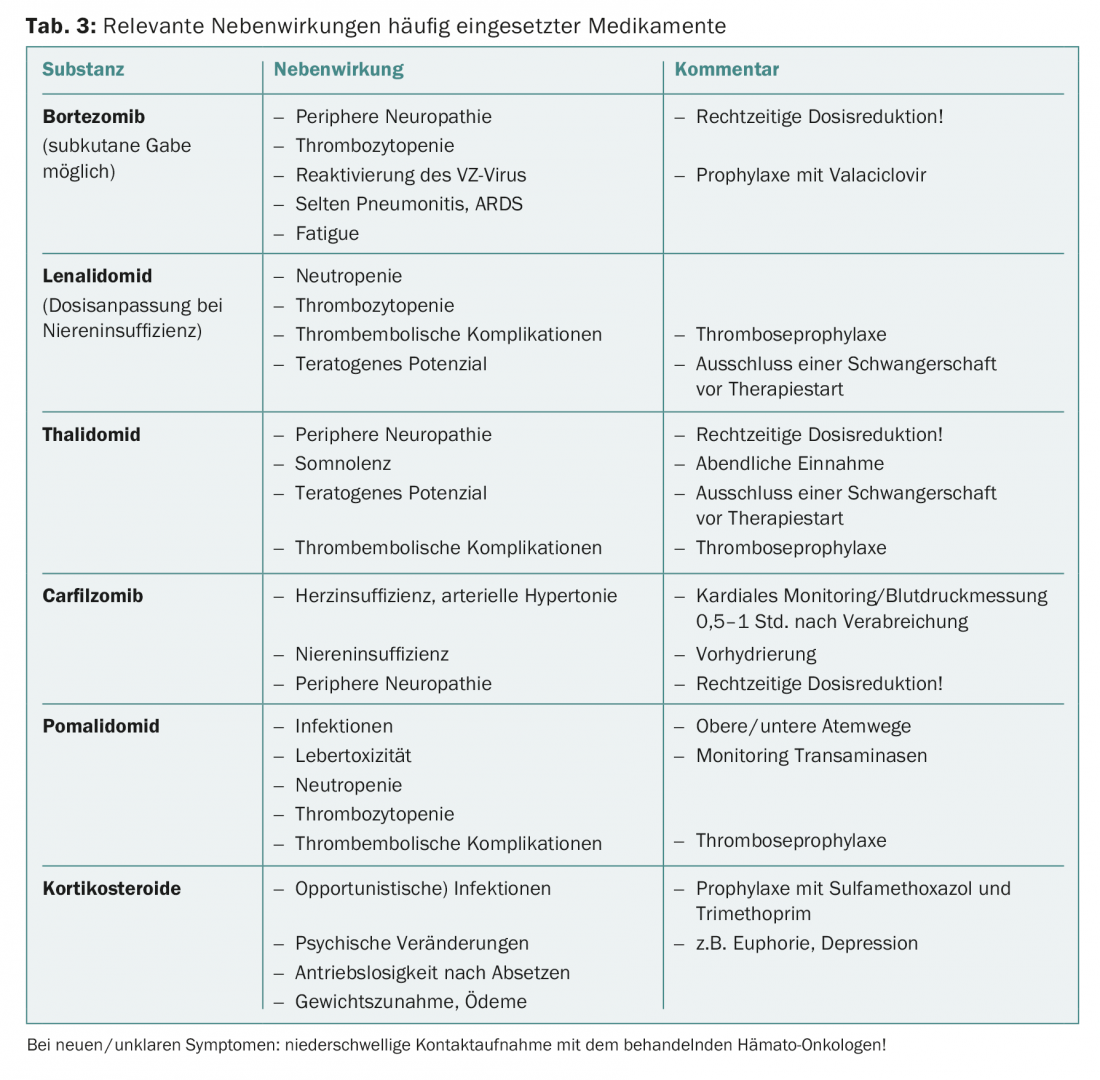

An overview of the most common side effects can be found in Table 3. Guidance on dose adjustment in elderly patients can be found in the literature [8].

All patients diagnosed with plasma cell myeloma requiring treatment should receive additional antiresorptive therapy with zoledronic acid, as this has also been documented to improve overall survival [9].

Second and later lines of therapy

In the case of symptomatic progression of the disease, it is again important to control it with effective therapy over as long a period as possible. Younger transplant-eligible patients who have not received HDCT/ASZT as part of first-line treatment should be offered it at relapse. In patients who have remained progression-free for at least 18 months after HDCT/ASZT, a second HDCT/ASZT can be discussed as salvage therapy after re-induction therapy. For example, a suitable induction regimen is the triple combination of bortezomib/doxorubicin/dexamathasone (PAD). In young patients with early relapse after HDCT/ASZT (<18 months) and/or unfavorable cytogenetic risk profile, the possibility of allogeneic stem cell transplantation can also be discussed with the transplant center in the relapse situation [10].

In non-transplant patients, if there is a good response to first-line therapy and a long progression-free interval, the same agents can be used in the sense of a “re-challenge”. If the progression-free interval is shorter, new substance classes should be used, as a sustained tumor response cannot otherwise be expected. Patients who initially received bortezomib should be treated with lenalidomide in the second line and vice versa. For later lines, other newly available agents may also be used, e.g., bendamustine, pomalidomide (third generation IMiD), or carfilzomib (second generation proteasome inhibitor). Also promising are results with elotuzumab, the first commercially available monoclonal antibody for myeloma therapy, in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone.

Experimental studies have shown that the HIV protease inhibitor nelfinavir can resensitize resistant myeloma cells to previously administered agents. This approach is currently being tested by the Swiss Association for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK) in two multicenter studies in patients with relapsed or refractory plasma cell myeloma. Nelfinavir is combined with lenalidomide/dexamethasone in one study (SAKK 39/10; https://clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01555281) and with bortezomib/dexamethasone in the other (SAKK 39/13; https://clinicaltrials.gov: NCT02188537). For more detailed information on available study results and current treatment recommendations for Switzerland, we also refer to a recently published review [11].

Outlook for new therapeutics

Recently, there has been increasing talk at congresses about the prospect of a cure for plasma cell myeloma patients. Immunotherapies of various kinds (IMiDe, antibody therapies, checkpoint inhibitors, CAR-T cells, “vaccines,” etc.) are raising hopes in this regard. Today, quite good long-term control of the disease is already a reality, and numerous drugs, some with new mechanisms of action, have either already been approved by the FDA and EMA or are at least in an advanced stage of clinical testing. This applies to first-line treatment for newly diagnosed plasma cell myeloma (NDMM) as well as relapsed or refractory plasma cell myeloma (RRMM) and high-risk smoldering myeloma.

New proteasome inhibitors and IMiDe: Four new intravenous and oral proteasome inhibitors are currently being investigated in NDMM and RRMM. Of these, phase III data are already available for carfilzomib (i.v.) (ASPIRE), with more to follow, and phase III trials are also currently underway for ixazomib (p.o.) (TOURMALINE-MM1, -MM2, -MM3). Pomalidomide is also being investigated in new, effective combination therapies.

Antibody therapies: Most common target antigens are CD38, SLAMF7 (CS1), CD138 and BCMA. The anti-CD38 antibody daratumumab and especially the anti-CS1 antibody elotuzumab have already been very well studied. Phase III data are available in RRMM for elotuzumab, which must be combined with other drugs to achieve efficacy (ELOQUENT-2). The same epitopes on plasma cells can also be used for immunotoxins (antibody-drug conjugates, e.g. indatuximab ravtansine) or for CAR-T cells.

Other substance classes: Phase III data are available on the HDAC inhibitor panobinostat in RRMM (PANORAMA1). Studies on specific HDAC6 inhibitors (ricolinostat) are ongoing. Checkpoint inhibitors (PD-1 and PD-L1) are being studied, combined with other T-cell-stimulating immunotherapies; efficacy in monotherapy was not found. Because of the frequency of cyclinD downregulation in myeloma, agents that specifically interfere with the cell cycle are being investigated, such as CDK inhibitors (seliciclib), nucleo-cytoplasmic transport inhibitors (SINE inhibitors, e.g., selinexor), and drugs that target kinesin spindle protein (e.g., filanesib/Arry-520), for which there is also a biomarker (AAG). In addition, as in other areas of hematology and oncology, there are approaches to interfere with signal transduction (PI3K/AKT/mTOR, RAF/MEK/ERK, JAK/STAT, NFkB) and to inhibit anti-apoptotic proteins (Bcl-2, Bcl-xL) (e.g. using ABT-199).

Due to the abundance of therapeutic options, finding the right combination and sequence of therapies for the right patient will be crucial in the future.

Literature:

- Rajkumar SV, et al: International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol 2014; (12): e538-548.

- Greipp PR, et al: International staging system for multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23(15): 3412-3420.

- Palumbo A, et al: Revised International Staging System for Multiple Myeloma: A Report From International Myeloma Working Group. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33(26): 2863-2869.

- Palumbo A. et al: Geriatric assessment predicts survival and toxicities in elderly myeloma patients: An International Myeloma Working Group report. Blood 2015; 125(13): 2068-2074.

- Larocca A, Palumbo A: How I treat fragile myeloma patients. Blood 2015.

- Attal M, et al: A prospective, randomized trial of autologous bone marrow transplantation and chemotherapy in multiple myeloma. Intergroupe Francais du Myelome. N Engl J Med 1996; 335(2): 91-97.

- Palumbo A, et al: Autologous transplantation and maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2014; 371(10): 895-905.

- Wildes TM, et al: Multiple myeloma in the older adult: better prospects, more challenges. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32(24): 2531-2540.

- Terpos E, et al: International Myeloma Working Group recommendations for the treatment of multiple myeloma-related bone disease. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31(18): 2347-2357.

- Giralt S, et al: American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplant, European Society of Blood and Marrow Transplant, Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network and International Myeloma Working Group Consensus Conference on Salvage Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation in Patients with Relapsed Multiple Myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2015.

- Samaras P, et al: Current status and updated recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of plasma cell myeloma in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly 2015: 145: w14100.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2016; 4(1): 24-29.