The treatment decision after cruciate ligament injury remains difficult. Instrumented stability measurement is an additional valuable parameter. Concomitant injuries to the meniscus and cartilage argue for (rapid) surgical treatment of all injured structures. Cruciate ligament preserving surgical techniques are a promising new option in the treatment of fresh anterior cruciate ligament injury. Diagnosis, treatment decision and surgery must be performed quickly to enable cruciate ligament preservation. In cruciate ligament reconstructions, technique and graft selection should be tailored to the needs of the individual patient.

Tearing of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) remains the most common sports injury leading to surgical intervention. The significance for the future development of a knee joint injured in this way should still not be underestimated, despite technical advances in surgical techniques. Especially in the presence of concomitant injuries to menisci and cartilage, the risk of posttraumatic osteoarthritis remains high [1].

Therapy of anterior cruciate ligament rupture – what’s new?

New aspects in the treatment of anterior cruciate ligament rupture have emerged in the last five years mainly due to the resurgence of cruciate ligament preserving interventions as well as technical improvements in cruciate ligament reconstructions, which have further reduced the invasiveness of surgery. Certain changes also occurred in graft selection.

On the other hand, the main problem in ACL injuries – i.e., the question of which patient requires surgical intervention at all – does not contain any new scientifically substantiated aspects. On the contrary, the new possibilities of cross-banding make this question even more difficult to answer at present.

Cruciate ligament preserving interventions

Primary cruciate ligament sutures, sometimes reinforced by synthetic augments, were propagated until the 1980s [2]. The sometimes high failure rate and the advent of arthroscopic cruciate ligament reconstruction led to a de facto displacement of these techniques [3]. At the same time, preserving the torn cruciate ligament would have clear advantages over replacement surgery, at least in theory. Thus, the proprioceptive capabilities of the ligament with its receptors and free nerve endings could be preserved, resulting in improved neuromuscular control of the knee. This in turn is considered important in the prevention of post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Additionally, there is no need for graft harvesting, which is associated with specific morbidity with any graft choice. The invasiveness in the joint is also significantly reduced, as no large bone tunnels have to be drilled into the joint.

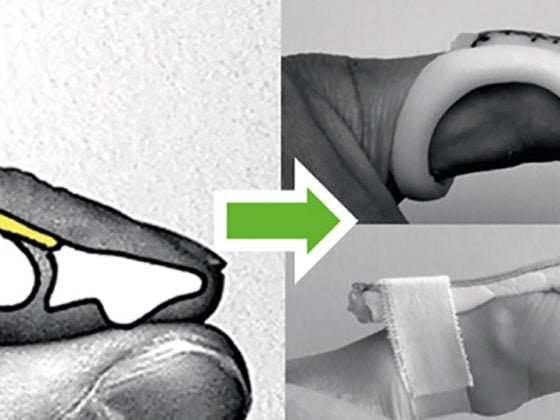

The main representative of these cruciate ligament-preserving techniques at present is certainly dynamic intraligamentary stabilization (DIS) (Ligamys™, Mathys AG) [4]. The philosophy behind this technique is that, on the one hand, the torn ligament is reduced to its anatomically correct position with transosseous sutures. On the other hand, these sutures are protected with a mechanically loadable construct, since their primary stability is very low compared to the forces involved. This also led to the well-known failure of cruciate ligament sutures alone. However, mechanical stabilization is not trivial because, on the one hand, a certain change in the length of the ligament augment during movement (anisometry) must be compensated for in order to prevent cyclic loading and thus failure of the augment. On the other hand, there must also be a continuous increase in the load on the healing ligament, as the mechanical properties of the ligament tissue adapt to the forces that occur. These properties are ensured by an implant system that contains a dynamic element (i.e., a spring) in addition to a polyethylene band that runs parallel to the ACL in the joint (Fig. 1). As a result, length changes of up to 8 mm can be compensated without losing the protective force for the ACL. The mid-term results of this technique are promising [5].

The Internal Brace™ (Arthrex, Inc.) follows a similar philosophy. In this case, primary reduction of the ligament is also achieved via a ligament suture, but stabilization is achieved by means of a static augment, in contrast to DIS [6].

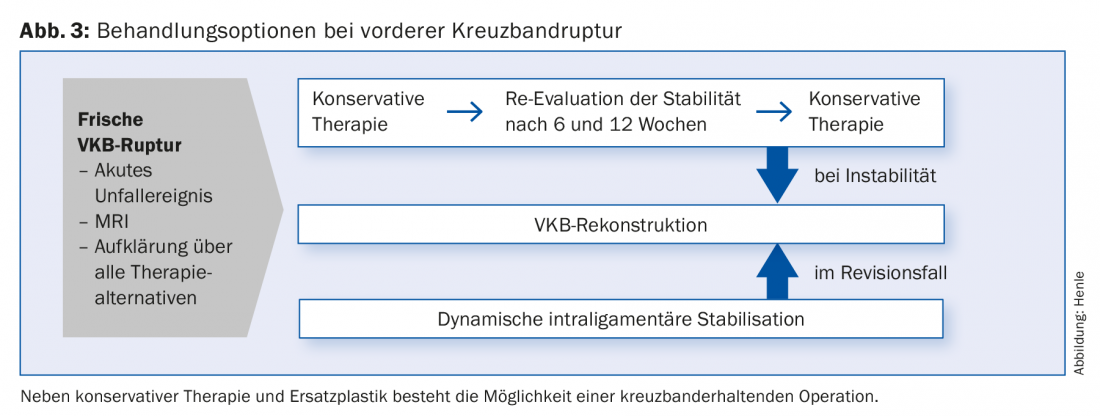

The difficulty of the new cruciate ligament preserving techniques is mainly the short time period in which the surgery must be performed after the injury – generally a maximum of three weeks. This places increased demands on logistics. Initial patient contact, MRI imaging, referral to the surgeon, and planning of surgery must be accommodated within this short interval. Conservative therapy “on trial” is thus also no longer feasible. Both lead to noticeable changes in patient management. Which patients are ideal candidates for cruciate ligament-preserving techniques is currently unclear.

Graft selection for cruciate ligament replacement surgery

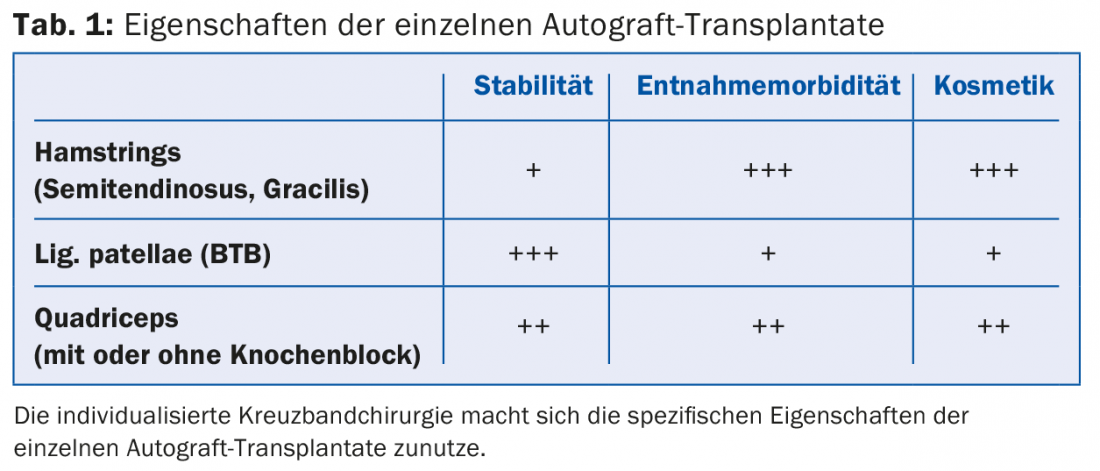

The debate over graft choice in cruciate ligament arthroplasty also continues. After a steady increase in the proportion of cruciate ligament reconstructions with hamstring grafts in recent years, the major registries now show some reversal of this trend, although the vast majority of cruciate ligament reconstructions continue to be performed with either the semitendinosus tendon alone or a combination of semitendinosus and gracilis tendons [7]. The proportion of primary ACL reconstructions with a quadriceps tendon graft in particular has increased significantly in recent years. Until now, the quadriceps tendon has been considered more of a revision graft, although it combines good mechanical properties (comparable to a patellar tendon graft) with lower harvest morbidity. This sometimes manifests itself in anterior knee pain in patients with a patellar tendon graft, particularly in kneeling positions. The reason for this may be that it is becoming apparent that somewhat better stability can be achieved with grafts from the extensor apparatus (lig. patellae or quadriceps tendon). Whether these small statistical differences are clinically relevant is difficult to assess. The different advantages and disadvantages of the individual grafts can be used consciously, which is subsumed under the aspect of individualized cruciate ligament surgery (Tab. 1).

The use of allografts for cruciate ligament reconstruction has declined sharply following the publication of large studies from the United States showing significantly increased revision rates. In the revision situation, when suitable autografts are no longer available, their use is certainly still a valid option.

Double Bundle

The idea of double-bundle reconstruction of the ACL is based on the fact that even in the anatomical cruciate ligament, functionally-anatomically different areas can be defined, which, depending on their course, stabilize the knee more in the antero-posterior direction (anteromedial parts, rather steep course) or rotational direction (posteromedial parts, rather flat course). With the double-bundle technique, these ligament components are now stabilized separately – this means that femoral and tibial two bone drills each have to be created. This makes the surgical technique much more demanding and the likelihood of intraoperative complications is greater. Revisions of double-bundle reconstructions are also usually more difficult due to more extensive bone loss. In technical measurements a better rotational stability could be shown by double bundle reconstructions. However, this did not result in a clinically relevant improvement of the outcome in terms of subjective stability, functional scores, or rupture rate. As a result, the number of double bundle reconstructions has again decreased significantly in the past three years and is currently practically negligible.

Which patient needs surgery?

The established treatment strategies are still conservative therapy with a rehabilitation program focused on improving neuromuscular control of knee function on the one hand, and surgical reconstruction in terms of ACL replacement surgery on the other. Although the options within surgical therapy regarding timing of surgery, choice of graft, fixation options, type and speed of postoperative rehabilitation are subject to continuous debate, the main issue remains in deciding which patient needs surgical therapy in the first place. Despite analyses of large patient collectives, it is still not possible to identify clear and objectifiable indication parameters to make a knowledge-based decision on a surgical procedure in the acute phase. A synthesis of history, clinical examination, and imaging is required, which then also leads to the therapeutic decision through a subjective evaluation by the physician.

In addition to patient age and activity level, quantification of instability is certainly a parameter that should be considered. With simple tools such as the Rolimeter™ (Aircast®, Allenspach Medical), the anterior laxity (Lachmann test) can be measured in comparison to the uninjured opposite side (Fig. 2) . Differences of more than 3 mm are more indicative of clinically relevant instability. For further prognosis of the knee joint, the rotatory instability recorded in the pivot shift test would be more informative than the Lachmann test. In the acute situation, however, this test is practically never feasible on the awake patient.

The evaluation of concomitant injuries to cartilage and menisci is also essential. The risk of posttraumatic arthrosis is disproportionately increased in combined ACL and meniscal injuries, so that reconstructable meniscal injuries clearly argue for a surgical approach with one-stage treatment of both injuries. Meniscal sutures performed early after injury and in combination with ACL reconstruction show significantly higher healing rates than meniscal sutures without ACL reconstruction. This is most likely explained by postoperative hemarthrosis, which increases biological activity in the knee.

From all of this information, an overall picture of the patient with their injury and activity needs emerges. The final decision on whether to proceed with surgery then also arises from interaction with the informed patient. Often young patients come to the consultation with quite precise, but not always correct information and ideas. It is important to explain the patient’s own decision-making process and to involve him or her in it. If the patient has made a decision with self-confidence, he or she will later be more willing to accept the resulting consequences.

The additional option of cruciate ligament-preserving surgery tends to make the treatment decision even more difficult, since a decision must be made directly in the acute situation as to whether or not the patient is suitable for such an intervention. The following parameters can be a decision-making aid: If the translational difference is 3 mm or less, there are no concomitant injuries, and the patient refrains from sports with stressful rotational movements (pivot mechanism), conservative therapy can be recommended. All other cases tend to argue for a surgical approach.

An overview of treatment options for anterior cruciate ligament rupture is shown in Figure 3.

Literature:

- Chalmers PN, et al: Does ACL reconstruction alter natural history? A systematic literature review of long-term outcomes. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014 Feb 19; 96(4): 292-300.

- Paessler HH, et al: Augmented repair and early mobilization of acute anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Am J Sports Med 1992 Nov-Dec; 20(6): 667-674.

- Fruensgaard S, et al: Suture of the torn anterior cruciate ligament. 5-year follow-up of 60 cases using an instrumental stability test. Acta Orthop Scand 1992 Jun; 63(3): 323-325.

- Henle P, et al: Dynamic Intraligamentary Stabilization (DIS) for treatment of acute anterior cruciate ligament ruptures: case series experience of the first three years. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2015 Feb 13; 16: 27. doi: 10.1186/s12891-015-0484-7.

- Eggli S, et al: Dynamic intraligamentary stabilization: novel technique for preserving the ruptured ACL. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015 Apr; 23(4): 1215-1221.

- Heitmann M, et al: Ligament bracing – augmented primary suture repair in multiligamentous knee injuries. Oper Orthop Traumatol 2014 Feb; 26(1): 19-29.

- Swedish Cruciate Ligament Register, Annual Report 2014, www.aclregister.nu.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(8): 14-18