Switzerland now has a meaningful registry on dialysis patients and treatments. This not only gives a good impression of the demographic situation and development of the Swiss dialysis population, but also enables important epidemiological and health policy questions to be answered in the medium to long term. Thus, it makes a relevant contribution to the medical care of these patients and to gaining new insights into disease mechanisms in chronic renal failure. Basically, it can also be used for quality control and improvement as well as a benchmarking tool.

In 2015, 296 million Swiss francs were spent on dialysis treatment for approximately 4500 patients with chronic kidney failure in Switzerland. This represents 0.4% of health care costs in our country. It is understandable that both health authorities and payers assert a need for data on the quality and effectiveness of the agents used in this area. In addition, however, it is also a key concern of nephrologists to have demographic data and outcome measures on the dialysis population in Switzerland. In contrast to the U.S., for example, where detailed surveys on dialysis treatments have been available for decades, corresponding information was lacking in Switzerland until a few years ago. In 2006, the Swiss Dialysis Registry was therefore founded (Swiss Renal Registry and Quality Assessment Program, srrqap). It is only since 2013, with the introduction of a contractual obligation to collect data, that largely complete data on dialysis patients and treatments treated in Switzerland are now available. The purpose of this article is to present the key findings from the available analyses of the first three years.

Demographics of the Swiss dialysis population

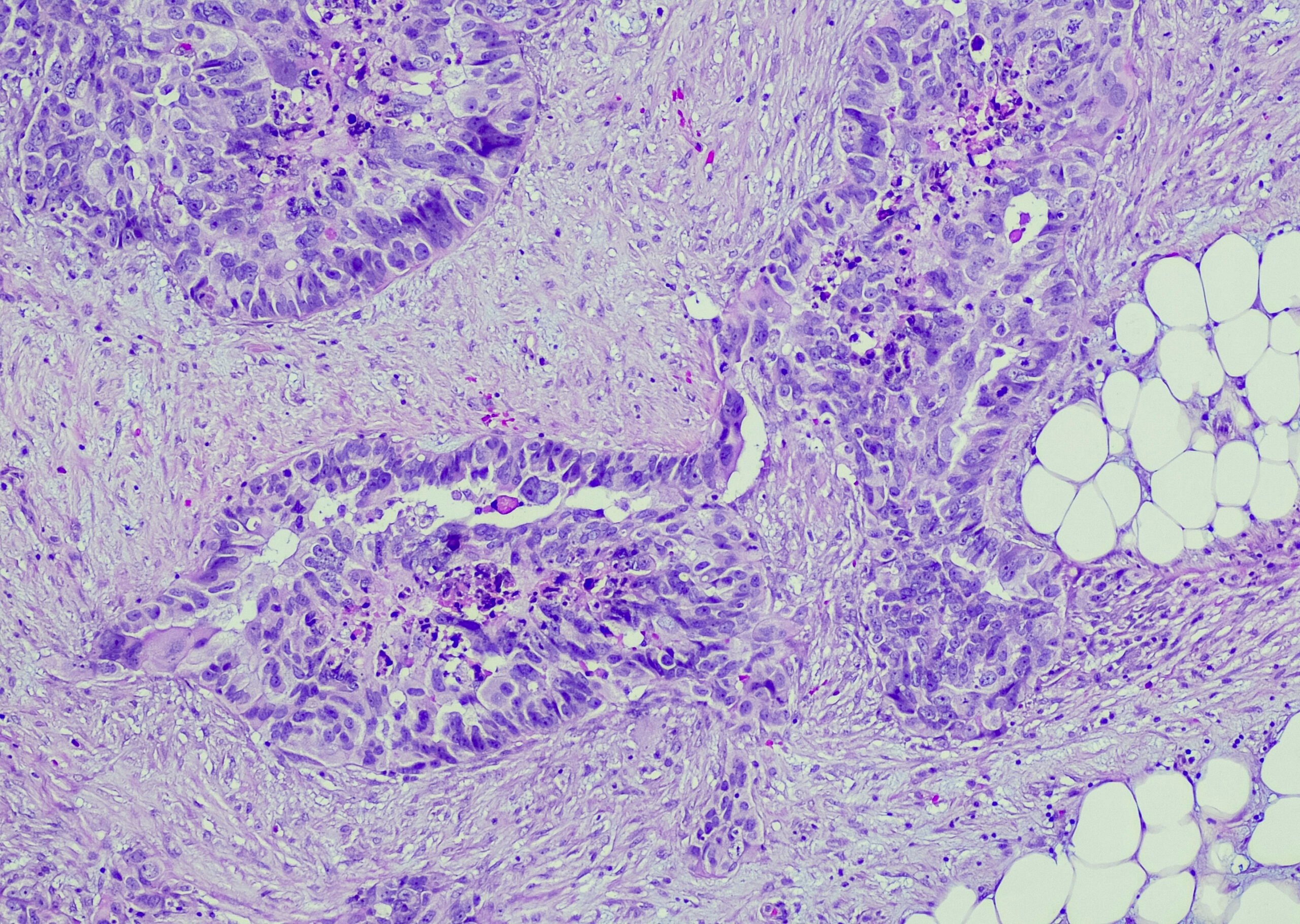

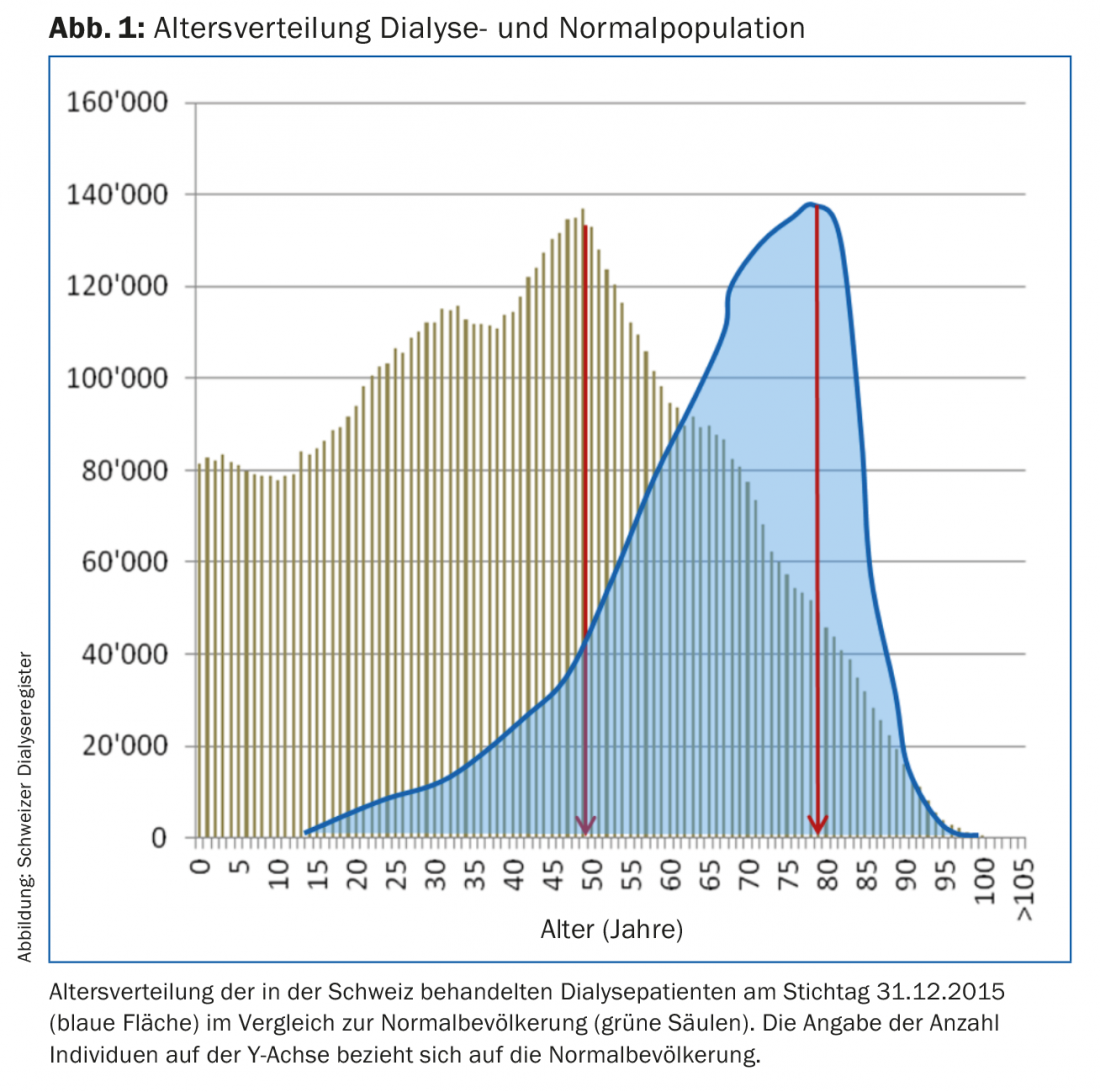

In 2015, 4453 dialysis patients were recorded in Switzerland. Based on a comparison with the insurers’ cost data, it can be assumed that the survey is nearly 100% complete. Compared with the previous year, this represents an increase of 5.6%. The average age in 2015 was 67.9 years, with one in two patients older than 70.8 years (Fig. 1).

Since 2013, the age structure changed by +0.6 years for both mean and median age. The question thus arises as to whether this increase is the result of longer survival on dialysis or older age at the start of renal replacement therapy. For this purpose, the age structure of existing patients (prevalent) and new patients admitted to a dialysis procedure (incisional) can be used. This shows that the prevalence of those aged ≥75 years increased from 37.2 to 40.7% between 2014 and 2015, whereas the incidence in this age category decreased from 36.8 to 30.7%. This means that patients with new-onset chronic renal failure tended to be younger during this period, and those on dialysis for more than a year tended to be older. However, due to the short observation horizon, these conclusions should be taken with reservations. In particular, it remains to be seen whether this will lead to an increasingly longer survival of dialysis patients. Information on survival resp. on mortality will only be meaningful once evaluations over several years are available. For patients who started dialysis in Switzerland in 2014, a 1-year survival of 91.7% was calculated. In comparison, this was only 82.7% in Europe (data from the European Renal Association/European Dialysis and Transplant Association registry, ERA-EDTA). This difference in favor of Switzerland is mainly due to a better outcome in the higher age groups of 65-74 years and in the ≥75-year-olds (CH: 91.6 and 86.9%, respectively; ERA-EDTA: 82.1 and 72.7%, respectively).

Causes and comorbidity of renal failure requiring dialysis.

Chronic renal failure is to a large extent a consequence of systemic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. For the first time, more precise information is now available on the cause and concomitant diseases of dialysis patients in Switzerland. Thus, in each of approximately 17% of patients, vascular ischemic resp. diabetic nephropathy declared as underlying renal disease. Accordingly, about one third of dialysis patients suffer from coronary heart disease or type 2 diabetes mellitus, as an expression of high cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, respectively. cardiovascular risk constellation in this population (Fig. 2).

Especially in the older age groups above 70 years, about half of the patients have a higher grade comorbidity based on the calculation by Charlson score. Thus, one in four dialysis patients in Switzerland is old and relevantly polymorbid. This is a circumstance that increasingly affects the care of these people. Not only is dialysis treatment itself more costly under these circumstances, but the medical care in general that patients require is becoming more demanding. Nevertheless, the results of dialysis therapy in our country are encouraging. As shown above, survival seems to be substantially higher compared to other European countries, at least for the available data on the first year after treatment initiation. Based on other published data from Switzerland, median survival from 2000 to 2010 was approximately six years after dialysis initiation, and 95% of 67-83-year-olds survived as long as 3.2-4.4 years [1].

In 2015, 560 or 12.6% of dialysis patients in Switzerland died. The most common cause of death was cardiac arrest/sudden cardiac death, at approximately 12%. Overall, cardiovascular complications led to death in more than 25% of patients. Other common causes were neoplasms (about 10%) and infections (about 9%). However, the second most common reason for death was dialysis discontinuation at the patient’s request (nearly 11%). This high proportion can certainly be explained by the age structure and polymorbidity of the Swiss dialysis population.

Encouraging developments can be seen with regard to transmissible infectious diseases, especially viral hepatitis. Compared to a nationwide survey in 1999, the proportion of hepatitis C-positive patients has been halved from 5 to currently 2.5% [2]. This is all the more positive as there is still no active vaccination available against HCV. In contrast, the prevalence of HBV has increased from 1.44 to 2.5% since 1999, but is still low by international standards.

Special aspects

A registry also always offers the opportunity to uncover and analyze special constellations in a patient collective. For example, it is noticeable that men clearly predominate in terms of proportion, accounting for 64% of the Swiss dialysis population (Fig. 3). The European average is around 60%, with all nations participating in the ERA-EDTA registry showing a clear majority of men (maximum: Norway 65%; minimum: Romania 56%). A more in-depth analysis of gender differences in the Swiss data shows that women are on average about four months older and almost eight months longer on dialysis. Also striking is a significantly lower morbidity with regard to cardiovascular diseases and risk factors. Thus, only 28.5% of women have CHD (men 41.5%), and only 27.8% have type 2 DM (men 33.8%) (Table 1).

Accordingly, “only” 20.5% of women but 23.2% of men died from cardiovascular complications in 2015. This is also interesting because the reverse is observed in the general population (in women, a cardiovascular cause was declared in 35% of deaths, compared to only 31.1% in men according to Healthcare Switzerland, Interpharma, 2016). Such epidemiological observations can generate scientific hypotheses, such as whether the uremic milieu modifies sex-specific risk for certain diseases. Similarly, from an epidemiological and health economic perspective, it is likely to be important to investigate the reasons for the higher prevalence of men on dialysis. Possible causes could be a lower burden of chronic kidney injury in female sex, or greater reluctance to initiate renal replacement procedures in women. To clarify the first possibility, more comprehensive data on the prevalence of CKD in Switzerland would be needed, which systematically do not exist. However, small studies do not indicate that there is a relevant sex difference, at least for early stages of chronic renal failure. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that, in the presence of established renal damage, men may have a more rapid progression of renal impairment due to a higher cardiovascular burden.

Another exciting aspect of the breakdown of gender-specific characteristics is that female dialysis patients in Switzerland are proportionally significantly more likely to have familial/hereditary or congenital kidney disease than men. While all other forms of renal impairment are distributed approximately 1:1 between women and men, the ratio for familial/hereditary and congenital disorders is approximately 1.5 “in favor” of female dialysis patients. Based on this observation, we performed the same analysis using European registry data in almost 300,000 patients – an analogous picture emerges. Again, the interpretation of these findings remains open for now. In particular, it will be necessary to scientifically investigate whether women are more likely to suffer from inherited and congenital renal disorders, or whether these are associated with a higher risk of developing renal failure in female gender.

One of the efforts of recent years has been to promote home dialysis treatments, the majority of which are performed independently by the patient in the form of peritoneal dialysis (“peritoneal dialysis”) or, in smaller numbers, home hemodialysis. Compared to center hemodialysis in a hospital or specialized medical practice, home treatments allow greater independence for the patient and are also generally less expensive. In 2015, a total of 10.4% of dialysis patients living in Switzerland performed home dialysis. The proportion of patients who started treatment for the first time this year was as high as 20%, which means that the target set by the contract partners (payers and service providers) has been achieved. Whether the proportion of self-treatments can be increased even further seems questionable, since home dialysis not only enables but also requires a high degree of independence. Accordingly, patients in this category are also significantly younger (age: 61.2 vs. 68.7 years) and less polymorbid (Charlson score: 3.8 vs. 4.5) than those treated with center hemodialysis.

Literature:

- Rhyn Lehmann P, et al: Epidemiologic trends in chronic renal replacement therapy over forty years: A Swiss dialysis experience. BMC Nephrol 2012 Jul 2; 13: 52.

- Ambühl PM, Binswanger U, Renner E: Epidemiology of chronic hepatitis B and C in dialysis patients in Switzerland. Schweiz Med Wochenschrift 2000; 130: 341-348.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(3): 22-26