The diagnosis of dementia should not be made lightly. It triggers a similar amount in the patient’s social environment as a cancer diagnosis. And yet it is important to educate and train everyone involved early on.

Alzheimer’s dementia, in its mild form, is usually initially noticeable in the social activities of daily life such as going out, meeting friends and family, interacting with neighbors, etc. Over time, instrumental activities of daily living are increasingly affected. Increasing difficulties become apparent in shopping, housekeeping, meals, and managing finances. In addition, aphasia/dysphasia and apraxia may already be present in this moderately severe form. Lastly, dementia in its severe form spreads to the basal activities of daily living, which include dressing and undressing, eating and drinking, personal hygiene, excretions, and transfers, associated with behavioral disturbances, agitation, and day/night reversal.

Physicians, and in particular primary care physicians as the first point of medical contact, are frequently confronted with dementia (and in this case Alzheimer’s dementia in more than half of the cases) when dealing with persons over 65 years of age. Stories about the problems that arise in everyday life are brought to them by the patients themselves, but much more frequently by their relatives. The question arises: How do I diagnose dementia and when is the right time to do so anyway? Should I treat them, and if so, how? Bernard Flückiger, MD, Head of Acute Geriatrics and Internal Medicine at Rheinfelden Hospital, gave an overview.

The assessment

If there is an initial suspicion, and if the indications also come from a relative, it is worthwhile “enlisting” him or her directly for the external anamnesis. For example, using the Mental Capacity Questionnaire for Older Persons (IQCODE), to be completed by the caregiver: on a five-point scale, does the person have more or less trouble remembering things involving family members and friends (such as birthdays, occupations, addresses) compared to two years ago? Does it escape him what day and month it is? Does he find things stored in a different place than usual worse? Does he regulate his finances less carefully resp. independent than before (transfers, bank transactions, pension)? The overall picture is completed by any Spitex, nursing and supervising doctors.

Of course, it is also important to take a clean medical history of the affected patient himself (especially with regard to the medications taken). Three questions can already provide initial clues here:

- Have you noticed lately that your ability to remember new things has diminished?

- Have relatives or friends made comments that your memory has gotten worse?

- Are you affected in your daily life by memory or concentration difficulties?

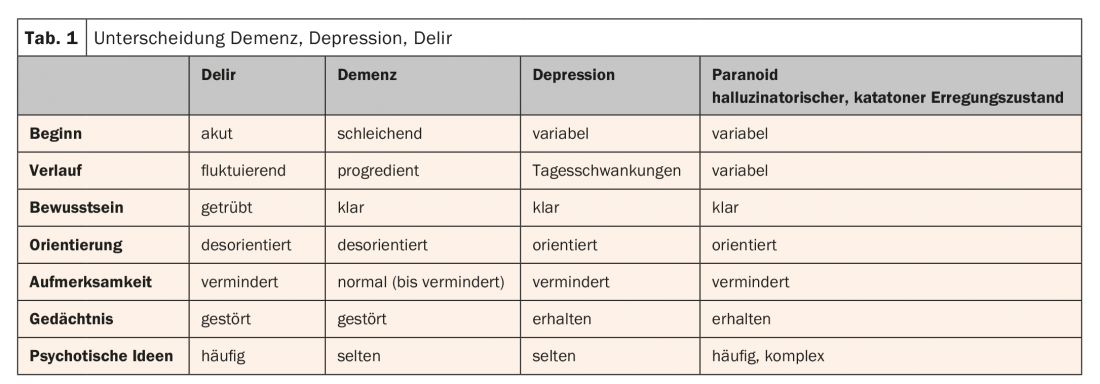

The next step is to look for specific organ disorders. Perhaps other important differential diagnoses such as depression, delirium, or psychiatric conditions can be ruled out by this time. More likely, however, the delineation of the three significant “Ds” of geriatrics, “dementia, depression, delirium,” is anything but straightforward (Tab.1). A geriatric assessment with mobility/gait analysis (e.g., Timed “Up and Go,” TUG), tests of fall propensity (e.g., Dual Tasking), nutrition (e.g., Nutritional Risk Screening, NRS), mood (e.g., Geriatric Depression Scale, GDS), sensory assessment, a medication history, and Confusion Assessment Method (CAM, delirium-specific) may help.

In addition, of course, there are numerous tools available to measure cognition, from the clock test, which is quite sensitive at the onset of dementia, to Mini Mental Status or MoCA (Montreal Cognitive Assessment) – also a good test for early dementia. Many of these are easily performed in a family practice setting.

Diagnosis: Mild dementia – what now?

Once the examinations have been completed, all the “puzzle pieces” have been collected and the overall picture clearly points to an incipient, mild dementia, one should not be afraid to also make the diagnosis, despite or precisely because of the knowledge of the devastating consequences of such a diagnosis. One thing is certain: the word “dementia” has a similar meaning to “cancer”; it will trigger an avalanche of associations, fears, anxieties and uncertainties for everyone involved. For this reason, the diagnostic discussion with the patient and relatives is of central importance. Not only to inform about the clinical picture and its progression, to discuss access to specific therapies and to find contact points or doctors. important contact persons, but also to initiate concrete steps at an early stage, to prepare the affected person and his or her environment for the coming period. It’s a matter of training, educating, advising on legal and social precautions, etc. “Relatives will reach their limits at some point, which is precisely why it’s all the more important to intervene early, develop strategies and provide professional support.”

If there is a certain degree of uncertainty and the tests initially suggest mild cognitive impairment (MCI) rather than mild dementia in the case of possible Alzheimer’s disease, the diagnostic interview is also helpful in explaining the suspected diagnosis and advising, for example, an appointment at the Memory Clinic. Admittedly, anti-dementia therapy should already be considered in this case as well.

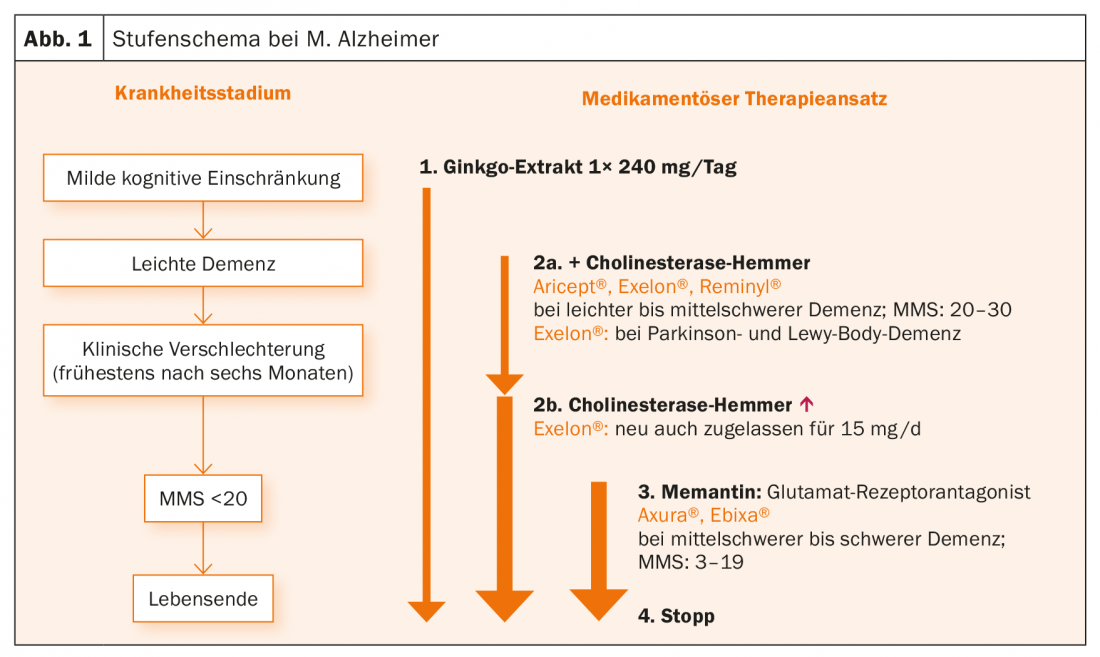

At present (and for some time), the treatment is as follows: Depending on the stage of the disease, Ginkgo biloba extract, cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine are used (Fig. 1). “Anti-dementia therapy should not be withheld from patients,” said the speaker. For MCI, a ginkgo biloba preparation at a dosage of 1× 240 mg/d is currently recommended. Recent studies in particular have clearly demonstrated efficacy in this indication. “You also don’t have to be afraid to introduce such a drug to anticoagulated patients; while it promotes blood flow, it’s not an actual antiplatelet agent. Studies have shown that it does not increase the risk of major bleeding.” For those diagnosed with dementia, a patch can be very useful as a delivery method for a cholinesterase inhibitor, as long as daily changes are not a problem. This reduces the usually extensive collection of tablets that the elderly patient already has to take alongside them. By the way, these should also be checked regularly, i.e. every three to six months. What medications does the older comorbid patient with progressive dementia really still need? The cholinesterase inhibitors delay entry into a nursing home – not by decades, since Alzheimer’s dementia ends in death after an average of ten years anyway, but by several valuable months and years. “I like to give the medications when patients show behavioral problems. They calm and stabilize. If the focus is on nocturnal restlessness, for example, Circadin® (melatonin) can also be considered. Finally, memantine is used for moderate to severe dementia. With this, too, we observe that behavioral abnormalities are favorably influenced (e.g., weepiness, crying or wandering) and neuroleptics and tranquilizers are saved.”

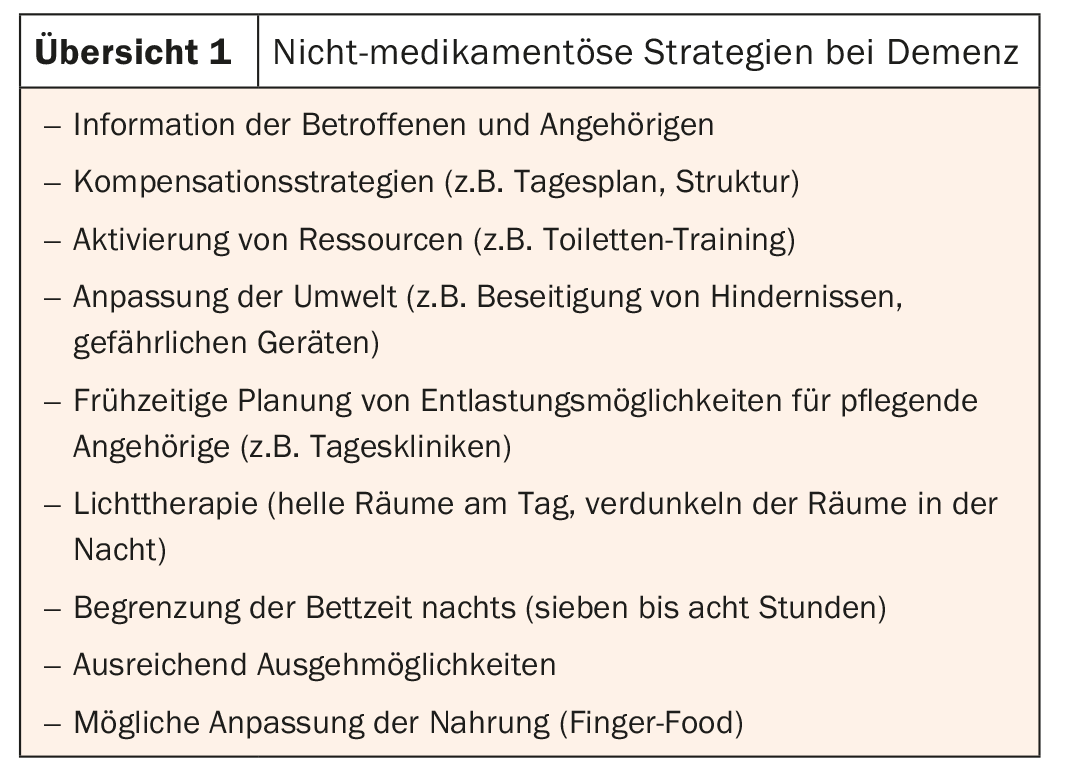

Non-drug strategies are at least as significant as drug strategies. Overview 1 summarizes them.

In conclusion, Alzheimer’s dementia is an extremely important diagnosis (not a secondary diagnosis!) and the disease itself remains a complex, intensively researched topic, which gives hope for further progress and insights into cause and therapy in the coming years.

Source: FomF General Internal Medicine Update Refresher, November 7-10, 2018, Zurich.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2019; 17(1) – published 12/20/18 (ahead of print).