Along with depression, social phobia is one of the most common mental illnesses. Early diagnosis and treatment are important. The latter can be psychotherapeutic or medicinal.

In both ICD-10 and DSM-5, Social Anxiety Disorder is classified under Phobic Disorders. Phobic fears are experienced predominantly or exclusively in narrowly defined, actually harmless situations. Outside of these anxiety situations, there is typically freedom from symptoms. People with social phobia are afraid of situations in which they are the center of attention. These may include public speaking, speaking in front of superiors, dealing with authorities, or team meetings. The focus is on the fear of being judged negatively or of behaving embarrassingly or awkwardly in these situations because of one’s own behavior or the appearance of feared symptoms (e.g., blushing).

Corresponding situations are therefore avoided or only endured with strong fear. Due to sometimes pronounced avoidance or safety behavior (e.g., meticulous preparation to regulate fear of failure in the short term), the quality of life is permanently impaired.

Before a diagnosis of social phobia is made, physical causes and diseases that can cause anxiety and anxiety-like symptoms must be ruled out. The key points here are a good medical history (including medication and substance history) as well as a physical examination and technical clarifications, such as ECG, blood pressure measurements and basic laboratory including thyroid values.

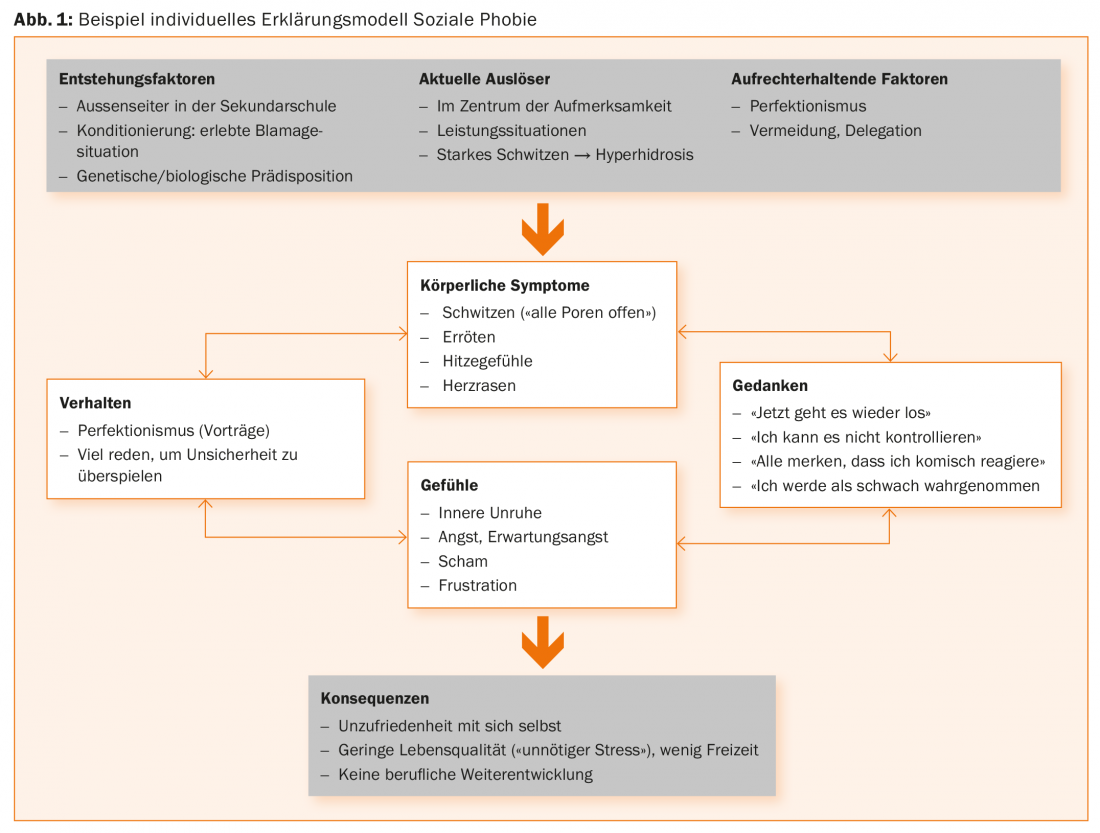

An important component of the diagnosis and analysis of anxiety symptoms is the detailed recording of an explanatory model of the anxiety disorder. In addition to identifying the personal factors that cause and maintain anxiety, this also includes the four components of anxiety. These four shares are:

- Physical symptoms

- Thoughts accompanying the fear

- Feelings accompanying the fear

- Behavior

The consequences of the person’s behavior are also verbalized with the person concerned.

Figure 1 shows such an explanatory model with examples.

Neurobiological explanatory model

Modern psychotherapy increasingly integrates neurobiological models into its explanatory models, which can help to understand the development and maintenance of anxiety symptoms. Therefore, at this point we would like to give a brief insight and in a later section we will show specific effects of group therapy on brain structure and function of people with social phobia. The amygdala or tonsil nucleus, located medially in the temporal lobe, plays a central role in the detection of a threat. Once the amygdala has “perceived” a stimulus as threatening, regions located in the midbrain and brainstem are activated, which then trigger the typical physiological symptoms of anxiety: Increase in respiratory and heart rate and blood pressure, muscular tension, sympathetic tone, activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical system (cortisol), and others. In parallel, other cognitive systems responsible for perceiving and processing stimuli are affected: attention and thinking are focused on potentially threatening stimuli, other content recedes into the background. On the neurobiological level, these two processes (peripheral-physiological, cognitive) are reflected in increased activations in the insular cortex on the one hand and in prefrontal and parietal cortical regions on the other. Such a fear response is regularly found when people are confronted with fear-inducing stimuli. In social phobia, however, these systems are involved to a greater extent and they also react to stimuli and situations that do not trigger a fear response in healthy individuals. Thus, increased activity and reactivity of the amygdala, insular cortex, and in prefrontal regions is generally found in social phobia [1,2]. In healthy individuals, prefrontal regions regulate emotion-processing structures such as the amygdala. In social phobia, studies examining changes in brain structure in social phobia found evidence that the connection between these prefrontal brain regions and the amygdala may be disrupted [3,4]. In addition, or perhaps in response, the cortex was thicker in certain prefrontal and parietal brain regions than in healthy individuals [5].

Psychotherapy

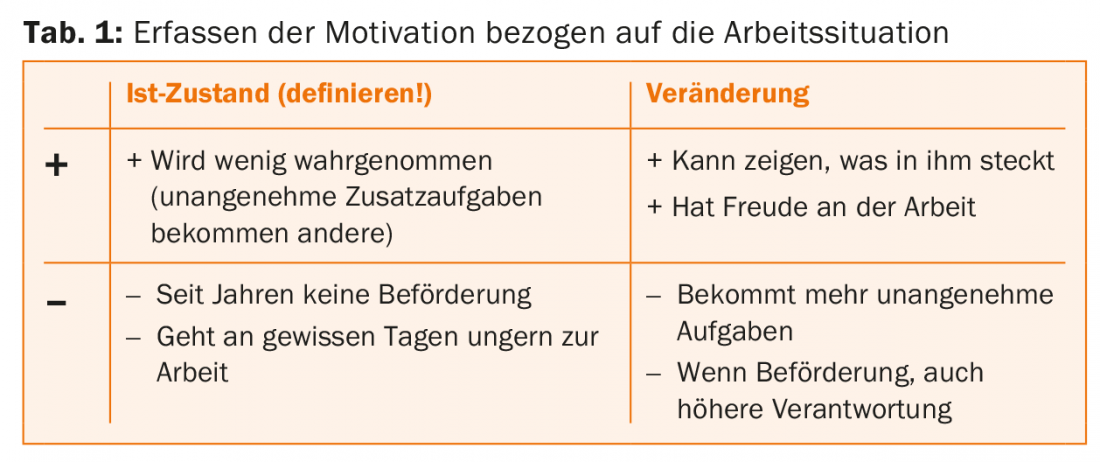

Once the diagnosis of social phobia is confirmed, cognitive-behavioral therapy should be provided as soon as possible. At the beginning of this it is necessary to clarify motivation and set realistic therapy goals. Motivation can be clarified, for example, with a 4-field board on advantages and disadvantages of the current and the improved situation. An example can be seen in table 1.

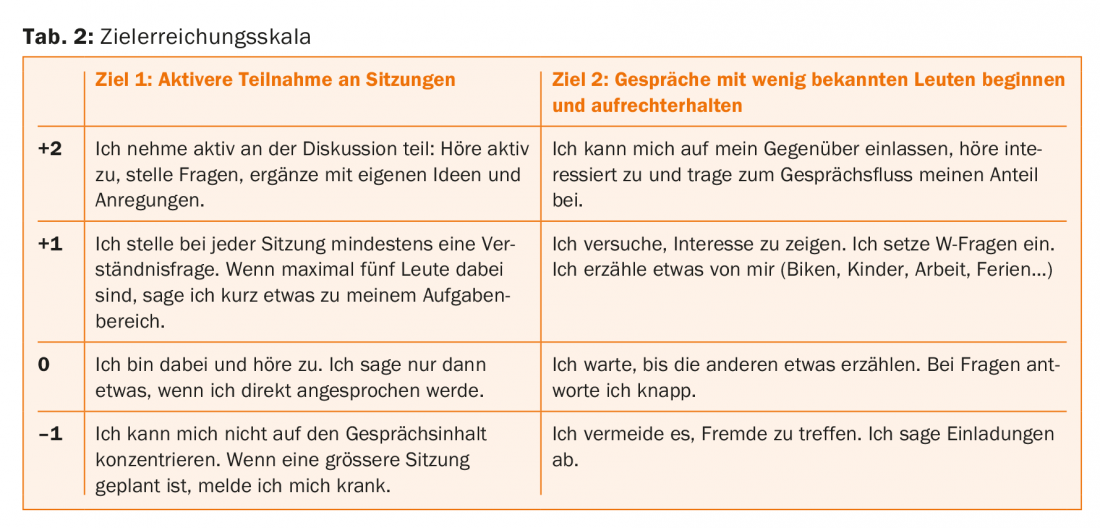

Therapeutic goals should be determined on an individual basis. Care should be taken to ensure that the goals reflect the patient’s daily life and are realistic. Graduation can be done with the help of a target achievement scale (Tab. 2).

Another central component of the therapy is exposure exercises, which should be carried out as close as possible to the everyday events of the affected person. However, since people with social phobia often avoid going to certain social situations and hardly trust themselves to do so at the beginning of therapy, group therapy is a good therapy option. The goal of therapist-led group therapy is to provide individuals with a protected exercise space with a variety of social interaction partners that allows them to engage in corrective learning experiences in group situations. Learned alternative strategies for dealing with anxiety can then be integrated piece by piece into everyday life according to individual goals. But even such a protected setting cannot always prevent sufferers from dropping out of therapy, especially if one or two sessions have already been missed for various reasons. Particularly for patients with social anxiety, there is a risk that absences may increase fear of future critical evaluation (“the group might think I missed on purpose because I’m sicker and overwhelmed”), making it more difficult to return to the group.

E-mail support in the course of group therapy: In a study we conducted, we investigated whether semi-individualized e-mail support between group sessions had an impact on the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral group therapy and on dropout rates in a sample of 91 patients with social phobia [6]. For the overall sample, we found that both interventions (group therapy only or group therapy with additional e-mail support) resulted in very good outcomes that were sustained over the twelve-month observation period. However, in a subset of patients with two or more missed group sessions, only those with additional email support were found to achieve significant and sustained symptom reduction (Fig. 2). Patients with two or more absences who did not receive additional email support appeared to stagnate and tended to show a higher dropout rate (47% without email support vs. 20% with email support; dropout rate overall sample: 19% without email support vs. 11% with email support). These results validate weekly email support between sessions as a way to reach patients at increased risk of dropout and thus support continuation of the therapeutic process even during repeated absences.

Neurobiological changes in the context of group therapy: As described, people with social phobia show changes in brain regions associated with fear. Accordingly, the question arose for us whether a “normalization” could be achieved with group therapy. Previous studies have found primarily reduced activations in occipital and temporal regions with behavioral therapy and also mindfulness-based group psychotherapy for social phobia [1]. In previous studies, after psychotherapy and after pharmacotherapy, amygdala activity was reduced, i.e., normalized. However, the question arose whether brain structural changes also regressed during ten to twelve weeks of group therapy. Twenty-four patients suffering from social phobia were therefore examined by magnetic resonance imaging before and after cognitive-behavioral group therapy [7]. After therapy, cortex thickness was reduced in parietal and prefrontal regions, and fiber connections between cortex and amygdala had also changed in the direction of normalization. The change in prefrontal cortex thickness correlated with the treatment success, the clinical symptom reduction (Fig. 3) . Using a network-based approach, we further showed that therapy increased structural connectivity in a network comprising frontal and limbic brain regions.

Drug therapy

Although cognitive behavioral therapy is often the therapy of choice [8,9], not all sufferers desire it. Accordingly, drug therapy should also be considered. In addition, drug therapy should be considered if the patient is severely impaired and cognitive behavioral therapy alone has not produced the desired effect. Other comorbid disorders (e.g., major depression) or existing contraindications (e.g., fresh myocardial infarction contra exposure) may also argue for drug therapy.

First and foremost, antidepressants may be considered. Of these, the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) paroxetine, sertraline, and escitalopram have the best evidence. Among selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSNRIs), this is the case for venlafaxine. Although benzodiazepines are effective in the short term, they should still not be offered. Benzodiazepines can only be given in justified individual cases (e.g., contraindication to standard medications), subject to a risk-benefit assessment. In order to ensure therapeutic success in the long term, whenever possible and desired by the affected person, drug treatment should be combined with cognitive behavioral therapy.

Take-Home Messages

- Social phobia is one of the most common anxiety disorders. Thus, along with depression, it is one of the most common mental illnesses.

- Early diagnosis and initiation of adequate treatment are important to prevent chronicity.

- Depending on the preference of the affected person, therapy can be psychotherapeutic or medicinal. The psychotherapy of choice is cognitive behavioral therapy, which can be delivered in an individual or group setting.

Literature:

- Bruhl AB, et al: Neuroimaging in social anxiety disorder – a meta-analytic review resulting in a new neurofunctional model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2014; 47(0): 260-280.

- Weidt S, et al: Common and differential alterations of general emotion processing in obsessive-compulsive and social anxiety disorder. Psychol Med 2016; 46(7): 1427-1436.

- Baur V, et al: White matter alterations in social anxiety disorder. J Psychiatr Res 2011; 45(10): 1366-1372.

- Baur V, et al: Evidence of frontotemporal structural hypoconnectivity in social anxiety disorder: A quantitative fiber tractography study. Hum Brain Mapp 2013; 34(2): 437-446.

- Bruhl AB, et al: Increased cortical thickness in a frontoparietal network in social anxiety disorder. Hum Brain Mapp 2014; 35(7): 2966-2977.

- Delsignore A, et al: E-mail support as an adjunct to cognitive-behavioral group therapy for social anxiety disorder: Impact on dropout and outcome. Psychiatry Res 2016; 244: 151-158.

- Steiger VR, et al: Pattern of structural brain changes in social anxiety disorder after cognitive behavioral group therapy: a longitudinal multimodal MRI study. Mol Psychiatry 2016 Dec 6. DOI: 10.1038/mp.2016.217 [Epub ahead of print].

- Keck M, et al: The treatment of anxiety disorders. Switzerland Med Forum 2013; 13(17): 337-344.

- Bandelow B, et al: S3 guidelines treatment of anxiety disorders. 2014.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2017; 15(5): 24-28.