Recommendations and counseling on career exploration and vocational suitability must be provided to patients with congenital heart defects during adolescence and are important prerequisites for a successful career and vocational path. Vocational counseling must be realistic and take into account both physical and mental capacity. The anticipated long-term course of the underlying heart defect in adulthood must be considered. In principle, children, adolescents and adults with congenital heart defects should be encouraged to exercise regularly. Advice on suitable types of sport and intensity of exercise must be given on an individual basis, taking all aspects into account. The extent of recommended physical activity depends on the severity of hemodynamically active lesions as well as daily symptoms and should be evaluated on an individual basis.

Due to the successes of pediatric cardiac surgery and steadily improving postinterventional care and follow-up, most patients with congenital heart defects now survive. This has led to the fact that there are now more adults than children living with congenital heart defects in Switzerland. However, these adults are not cured and many have residual hemodynamically unfavorable findings and/or reduced exercise capacity. Many are also pacemaker or intracardiac defibrillator wearers. These factors have a decisive influence on job suitability. Therefore, career counseling by the specialized medical profession has an important role to play in optimal career choice and planning.

In addition to career choices, leisure activities and sports are also important aspects of shaping one’s life. In this regard, it is also important to carefully assess the performance spectrum and possible complications already in childhood and adolescence in order to be able to make individualized recommendations for leisure activities and sports activities. This article reviews existing recommendations in patients with congenital heart defects.

Fitness for employment

Learning a suitable profession and lasting professional activity in this profession are important aspects for satisfaction in life. Of course, this also applies to patients with a congenital heart defect. Gainful employment is important for a steady income and social status. In our society, it is also a central component of social integration and self-esteem. However, the ability to obtain and maintain employment does not depend solely on physical ability. Mental capacity, motivation, and interaction with peers, as well as potential discrimination from society, are important factors in finding (or not finding) a suitable occupation. Although the majority of adults with congenital heart defects have learned a trade and can also find a job, more patients work part-time compared to the heart-healthy population. Several studies have shown that work participation depends on the severity of the heart defect and the educational level of the patients [1,2]. For example, patients older than 25 years with a complex heart defect are significantly more likely to be out of paid work compared to the normal population. However, patients with paid work also face various problems in their career advancement: lack of protection from discrimination based on physical disability (especially among private employers), limitation in the choice of profession, lack of opportunities for promotion, and lack of advancement (partly due to frequent absences for medical reasons, doctor’s visits, hospitalizations, etc.). In one survey, more than half of patients reported at least one career-related obstacle, and the most common reasons for job abandonment were physical disability, fatigue, and emotional instability [1].

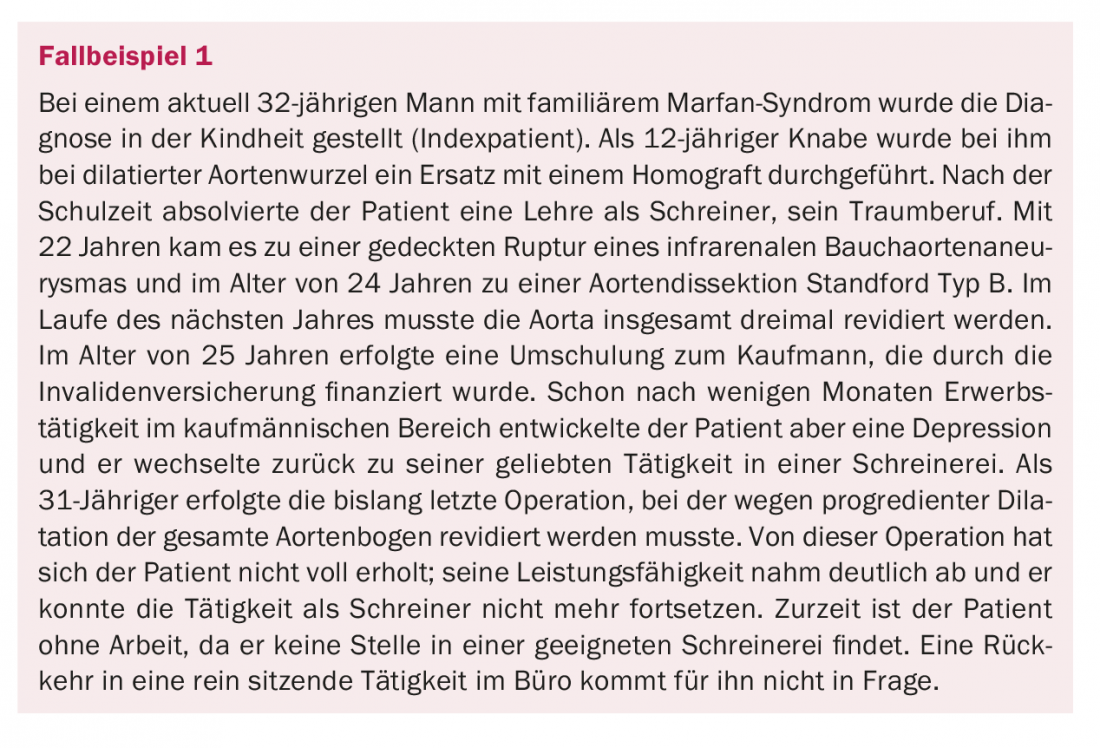

Appropriate vocational counseling is part of the responsibility of the treating physicians. Advice must be realistic and take into account both physical and mental capacity. It is important to also anticipate the expected course of performance in adulthood to allow the patient to make an “informed career choice.” The consultation should be individual. A simple categorization of career choice recommendations based on the presenting cardiac defect alone falls short because of the variation in severity within an entity and the variability in clinical courses. Specific clinical pictures and problems (e.g. cardiac arrhythmias, aortic diseases, connective tissue diseases, mechanical valve prostheses, etc.), where a priori certain activities are not recommended, need special attention. As described in Case Study 1 , physically demanding work (e.g., carpenter, forester, construction worker) is not appropriate for patients with connective tissue disease (e.g., Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome) and other aortopathies, and this recommendation should be discussed at the time of career exploration in adolescence. Patients with existing arrhythmias or with a high risk of suffering arrhythmias must be advised against occupations where there is a danger to self or others due to a concentration disorder caused by the arrhythmia (drivers of motor or transport vehicles, construction workers, especially roofers).

In Switzerland, protection against discrimination on the basis of disability in employment is relatively weak, especially in the private sector. However, those affected do not have to inform their employer about all health impairments. There is only a duty to inform if the heart defect has an influence on the required work performance or if a deterioration in health must be expected. In case of doubt, it is advisable to point out physical and emotional impairments (difficulty concentrating, fatigue after several hours of work) already at the time of hiring, so that specific adjustments can be made together with the employer (flexible working hours, reduced time pressure, freer organization of work). However, private employers are not required to implement these adjustments.

If there is a mental or intellectual impairment, e.g. in the context of a syndrome (trisomy 21, William Beuren syndrome, etc.), professional integration should be promoted in cooperation with support institutions. Various institutions can be consulted for advice on questions and support with career choices and work-related problems. Worth mentioning is the association “Supported Employment Switzerland” (www.supportedemployment-schweiz.ch), which has set itself the goal of “supporting people with disabilities or from other disadvantaged groups in obtaining and maintaining paid work in companies of the general labor market”. Advisory support is also provided by the Procap Association (Association for People with Disabilities, www.procap.ch).

Sports fitness

Counseling of children and adolescents with congenital heart defects has changed over the past few decades. Whereas in the past rather restrictive behavioral measures regarding sports activities were applied [3], the recommendations for patients today are much more liberal. In principle, children, adolescents and adults with congenital heart defects should be encouraged to engage in regular physical activity. “Sports bans” are indicated only in very few cases [4]. Sudden cardiac death is a rare event overall in patients with known congenital heart defects [5] and participation in sports activities is not associated with more cardiovascular complications [6]. Therefore, non-competitive sports activities are usually suitable for most patients.

Nevertheless, adults with congenital heart defects are less involved in sports activities than the heart-healthy population [6]. Especially in children and adolescents, overly protective behavior often leads to late effects. Social isolation, lack of self-confidence, and obesity (with consequent late cardiovascular complications) may be facilitated by lack of exercise.

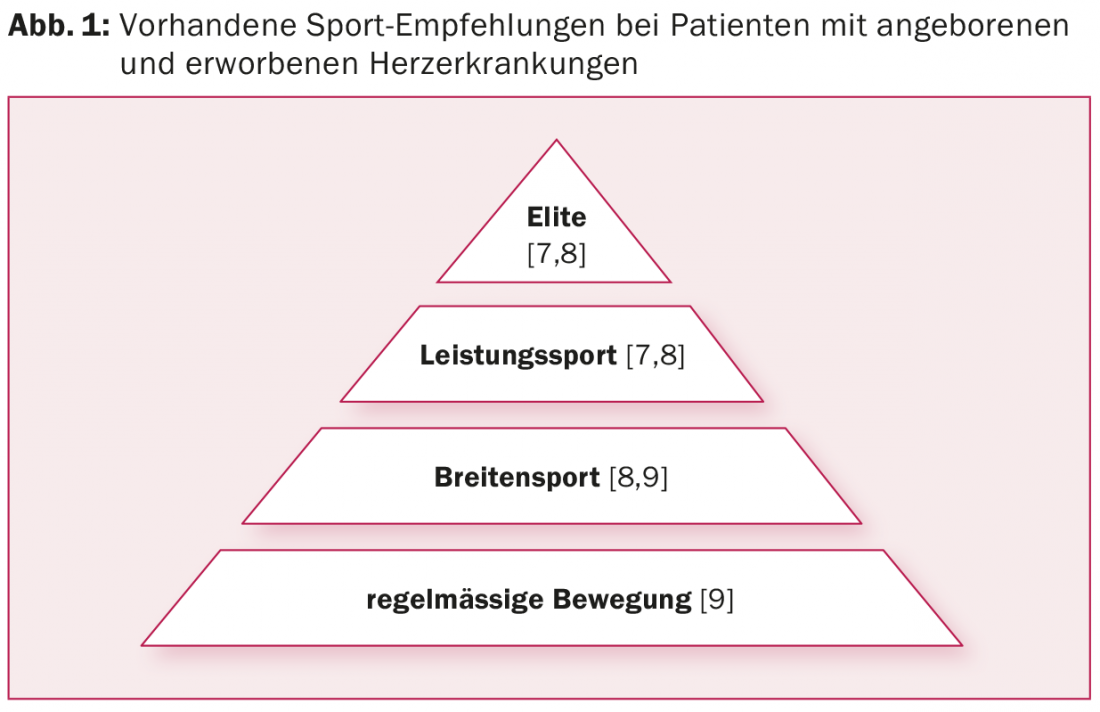

The extent of recommended physical activity depends on the severity of hemodynamically active lesions and daily symptomatology. There are various guidelines and recommendations for assessing fitness for sport and for sporting activity – both for healthy people and for people with heart disease, for recreational athletes as well as for athletes (Fig. 1) [7,8].

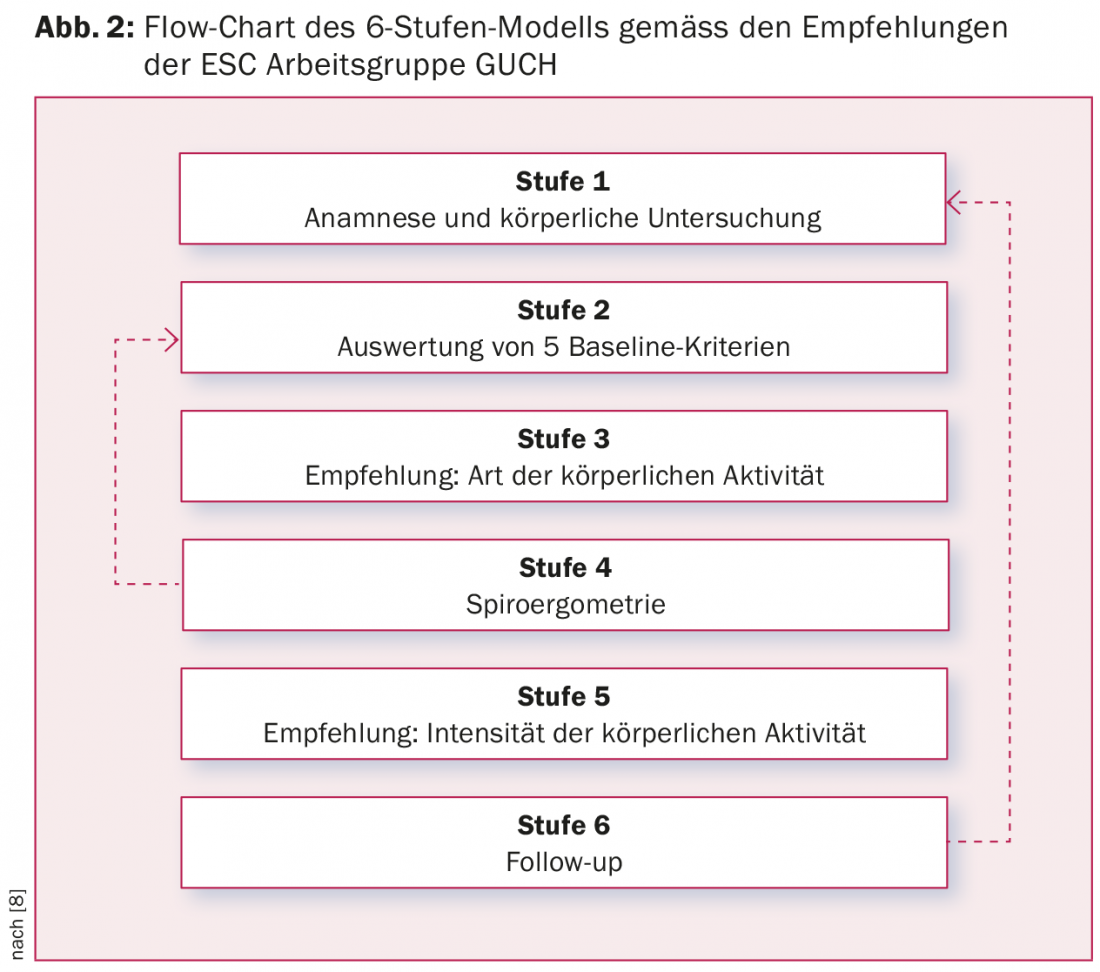

However, patients with congenital heart defects are not specifically mentioned in these guidelines. A recent paper from the GUCH working group of the ESC attempts to fill this gap with individualized exercise recommendations for adults with congenital heart defects [9]. The recommendations are based on a 6-stage model (Fig. 2) and, in addition to history and diagnosis, take into account five key clinical performance parameters (ventricular function, pulmonary arterial pressure, aortic pathologies, arrhythmias, and oxygen saturation), type of performance (static vs dynamic exercise), objective spiroergometry parameters, and exercise intensity.

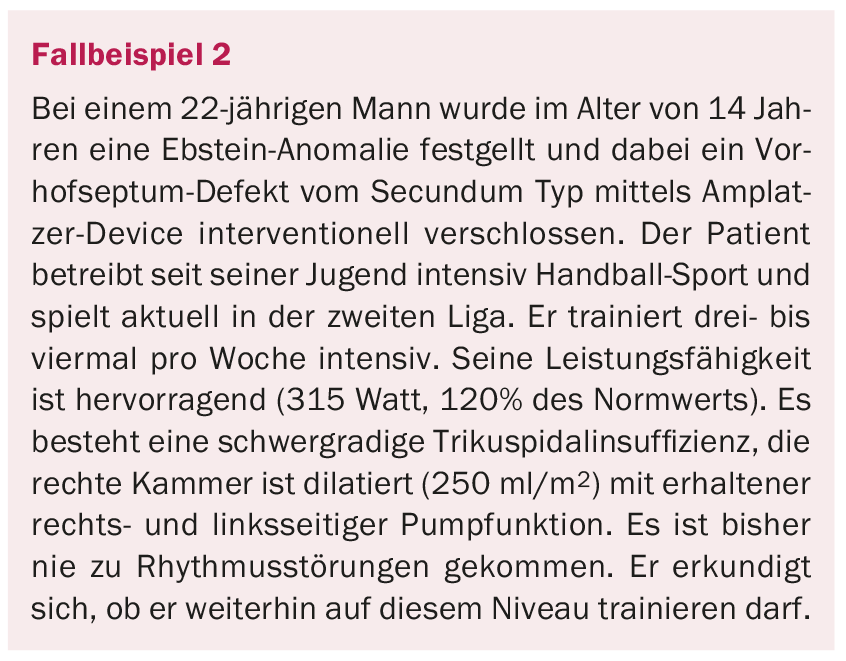

Based on these recommendations, the patient from case study 2 is likely to continue to participate in high-intensity sports.

Special recommendations apply to patients with pacemakers and intracardiac defibrillators. Also not mentioned are recommendations for diving in patients with shunt vitias or patent foramen ovale (PFO). Detailed guidelines on this can be obtained from the Society for Underwater and Hyperbaric Medicine (SUHMS) at www.suhms.org.

Finally, it should be pointed out that the sports assessment and the resulting recommendations in all patients with complex congenital heart defects should be performed by cardiologists specialized in this field, taking into account all individual aspects.

Literature:

- Kamphuis M, et al: Employment in adults with congenital heart disease. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002; 156: 1143-1148.

- Kokkonen J, Paavilainen T: Social adaptation of young adults with congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol 1992; 36: 23-29.

- Gutgesell HP, et al: Recreational and occupational recommendations for young patients with heart disease. A Statement for Physicians by the Committee on Congenital Cardiac Defects of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart Association. Circulation 1986; 74: 1195A-1198A.

- Graham TP, et al: Task Force 2: congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 45: 1326-1333.

- Garson A, et al: Ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death in children. J Am Coll Cardiol 1985; 5: 130B-133B.

- Opic P, et al: Sports participation in adults with congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol 2015; 187: 175-182.

- Pelliccia A, et al: Recommendations for competitive sports participation in athletes with cardiovascular disease: a consensus document from the Study Group of Sports Cardiology of the Working Group of Cardiac Rehabilitation and Exercise Physiology and the Working Group of Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2005; 26: 1422-1445.

- Takken T, et al: Recommendations for physical activity, recreation sport, and exercise training in paediatric patients with congenital heart disease: a report from the Exercise, Basic & Translational Research Section of the European Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation, the European Congenital Heart and Lung Exercise Group, and the Association for European Paediatric Cardiology. European journal of preventive cardiology 2012; 19: 1034-1065.

- Budts W, et al: Physical activity in adolescents and adults with congenital heart defects: individualized exercise prescription. Eur Heart J 2013; 34: 3669-3674.

CARDIOVASC 2015; 14(3): 9-12