In the course of its disease, rheumatoid arthritis leads to hand and foot destruction in affected patients in particular. In the area of the foot, the forefoot is affected more frequently than the hindfoot. Current basic medical procedures are now very effective in reducing inflammatory rheumatic activity, but this means that patients often present very late.

In the course of its disease, rheumatoid arthritis leads to hand and foot destruction in affected patients in particular. In the area of the foot, the forefoot is affected more frequently than the hindfoot. Current basic medical procedures are now very effective in reducing inflammatory rheumatic activity, but this often results in patients presenting very late, but then with irreversible joint destruction.

Especially the foot deformities lead to a considerable restriction of the mobility and independence of the rheumatic patient. The treatment is carried out depending on the stage, taking into account the wishes and expectations of the patient and in particular also with regard to the frequent multimorbidity of the rheumatic patient. In addition to basic medication, conservative physical therapy and physiotherapy are carried out in the early stages, as well as technical shoe care with insoles, shoe fittings and even orthopedic custom-made shoes.

After exhaustion of conservative therapy and already advanced foot deformities, there is then an indication for surgical therapy. Resection arthroplasties in the forefoot, which have been tried and tested for decades, are still used here as the “gold standard”. Surgical therapy in particular must be prepared very carefully, since the risk of foot surgery is always increased and is further increased in rheumatic patients, especially due to the cortisone therapy, which often lasts for years, and the overall fragile skin and circulation conditions.

Etiology and clinic of rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an inflammatory, often chronic and progressive systemic disease of the connective tissue. It can affect both the truncal and peripheral small joints and, in addition, the tendon sheaths and bursae lined with synovialitis. In the case of a long-term course, infestation of internal organs is also possible. The disease can occur at any age. The main age of manifestation is between 30 and 50 years of age, with women being affected 3 times more often than men. The clinical picture is highly variable. In most cases, the disease begins insidiously, but not infrequently (15 to 30%) acutely with episodes of fever and a pronounced feeling of illness. The joint involvement pattern can also be highly variant and can be monoarticular, oligoarticular, or polyarticular. The symmetrical joint involvement typical of RA is absent in the early stages in approximately 30% of patients. Just like the onset of the disease, the course of disease development can vary widely. The actual manifestation of RA is often preceded by a series of prodromal syndromes. These include, for example, fatigability, loss of appetite, weight loss, increased sweating of the hands, transitory joint and muscle pain, morning stiffness, and intermittent joint swelling [1].

These symptoms can develop over a long period of time. In addition to these nonspecific symptoms, rheumatoid arthritis is characterized by typical symptoms such as chronic synovialitis, usually of several joints. Clinically, the inflamed joints are swollen, hyperthermic, often pressure-dolent, and painful to move. The metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints of the fingers, wrists, and metatarsophalangeal joints of the toes are particularly affected. Laboratory chemistry reveals elevated levels of inflammation, such as blood cell sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP), as well as evidence of rheumatoid factor (RF) or anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies. Radiologically, usures and erosions, joint deformities such as ulnar deviation of the long fingers, buttonhole or swan-neck deformities of the fingers, and in the foot, deformities with buckling splayfoot and claw toes appear during the course of the disease [4].

Pathogenesis of the rheumatoid forefoot

If one deals with the pathogenesis of the rheumatic forefoot, one must not disregard the changes in the area of the hindfoot. Changes in the hindfoot always have an influence on the overall foot and especially on the deformities of the forefoot. This has further consequences when it comes to surgical treatment of rheumatoid forefoot deformities [10].

As is always the case with rheumatologic joint deformities, synovialitis is also prominent in forefoot deformities. Accompanying tenosynovialitis of the flexor tendons is often found. The spread position of the MTP joints is initiated by the changes in the rheumatoid hindfoot and midfoot. As a result, the transverse arch of the forefoot is lost. As a result, the MTP joints leak plantarly and cause painful, often pronounced inflammatory pressure calluses with bursae. The metatarsal heads continue to advance plantarly, while the proximal phalanx bases subluxate dorsally due to weakening of the plantar capsule and the inserting short flexor tendons. This results in increased tension of the long flexor tendons, which then cause the usually accompanying claw position of the peripheral toes. As a result, the long flexor tendons shift interdigitally to dorsal fibular. In the final stage of forefoot deformity, progressive inflammation occurs in the area of the plantar joint capsule, the so-called plantar plate, due to both joint synovialitis from dorsal and progressive bursitis from plantar. Eventually, plantar perforations of the skin with synovial fistula formation may occur. Ruptures of the long flexor tendons are also frequently associated with this. Of critical importance is understanding the interaction between changes in the hindfoot and midfoot and those in the forefoot. Thus, rearfoot changes can be considered the cause of forefoot deformity, but also as its consequence. In principle, the same considerations apply to the changes in the back and midfoot area. Joint synovitis causes loosening of the capsular ligamentous apparatus and instability of the talonavicular joint. The talus migrates plantar medial with concomitant rotation and valgus axis deviation of the calcaneus. This results in the typical valgus axis malposition of the hindfoot in combination with flattening of the longitudinal arch of the foot in the midfoot and forefoot region. The combination of the described deformities leads in the final stage to the “pied rond rhumatismale”. Patients complain of rolling pain, and some complain of pain at rest at night. Mobility and quality of life are increasingly limited by a small-stepped and awkward gait pattern [9] (Fig. 1-4).

Orthopedic shoe care options

Of central importance for inflammatory rheumatic foot deformities and complaints is conservative therapy with the provision of insoles, shoe adjustments or fitting of a custom orthopedic shoe. This care is important both to avoid surgical measures and to maintain the mobility of the rheumatic patient and postoperatively to stabilize and maintain therapy results in the long term. Inflammatory foot deformities can be divided into three stages [5,6]:

Stage I: Functional disturbances with preserved possibility of active correction during weight bearing in standing position.

Stage II: Dysfunction with the possibility of passive correction or active correction in relief.

Stage III: Fixed foot deformities without possibilities of passive or active correction.

Depending on the principle of action, a distinction is made between corrective, supportive and bedding insoles. Rheumatism patients generally require a so-called sandwich insole made of materials of different degrees of hardness, which on the one hand meet the requirement for firm supporting elements, and on the other hand allow soft bedding over prominent and painful areas with inflammatory changes. It is important to warn against metatarsal supports that are too high and too hard or too far distal, which are often not accepted in rheumatic patients due to the sensitive skin conditions.

Shoe finishes are recommended mainly on the sole, the toe cap and the upper leather. In particular, rolling techniques are used for shoe trimming on the sole. The normal roll-off point in a shoe is just behind the metatarsal heads. The more proximally the joints are arthritically altered, the more the rolling point of the foot can be shifted back in the sense of a midfoot roll or a recessed midfoot roll. The basic requirement for this is that there is a slightly increased toe lift of the shoe. Earlier rolling of the shoe relieves pressure on the proximal joints. To relieve the proximal joints, a buffer heel can also be inserted as a cushioning element, among other things. To improve the stability of the rheumatism patient, a continuous sole in the sense of a wedge heel is recommended.

Sole stiffening in combination with a rolling aid is an important aid for painful destruction of the rheumatoid foot. It guarantees that the plantar surface of the foot is essentially immobilized and painful flexing of the foot in the rolling act of the shoe is prevented. The widely used butterfly roll is not without problems in rheumatoid foot. On the one hand, it leads to a significant reduction in pain over the relieved areas; on the other hand, it involves the risk that, in the case of flexible deformity, the affected metatarsal heads will dip into the soft area of the butterfly roll, thus increasing the deformity. In a purely flexible rheumatoid forefoot deformity, a butterfly roll is rather contraindicated [2].

In the case of complex rheumatic foot deformities in the final stage, which can no longer be adequately treated by insoles and shoe fittings, an orthopedic custom shoe is then indicated. For all shoe-related fittings, it must be remembered that the rheumatic patient also has disabilities in the upper extremities, especially in the hand area, which prevent the shoes from being laced up independently. Therefore, appropriate shoes should be equipped with Velcro fasteners or quick-release fasteners.

Surgical procedures of the rheumatic forefoot

After exhaustion of all conservative measures, in particular basic drug therapy, physical therapy and physiotherapy, infiltration techniques and orthopedic shoe fitting, the indication for surgery should be considered if painful functional limitations and malpositions persist. The surgical goals are pain-free walking and shoelessness of the feet, if possible also the restoration of walking and rolling function [3].

The preparation for surgery should always be made with restraint, also in view of the multimorbidity of the rheumatic patient. In consultation with the internal rheumatologist, the basic medication to be paused perioperatively must also be discussed. Contraindications for surgical procedures on the rheumatoid forefoot are infections, circulatory disorders, poor general condition with serious comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, and when cosmetic aspects of the patient alone are the primary consideration. Furthermore, hindfoot deformities must also be considered, which usually require surgical treatment with a stabilizing arthrodesis or a functional ankle joint endoprosthesis before forefoot deformities. Before an electively planned surgical intervention, a radiological examination with conventional radiographs must be performed in addition to the clinical examination. This reveals the typical radiological changes with joint space narrowing, demineralization near the joint, and joint erosions documented in the five different stages according to Larsen, Dale, and Eck (LDE). The operation is performed in the supine position on the operating table. Special care must be taken with the multiple joint involvement of the rheumatic patient and the possibly limited functions and contractures of the other extremities. Furthermore, the skin of the rheumatic patient is particularly vulnerable to years of cortisone use with regard to the application of blood-emptying cuffs and the application or removal of adhesive sheets. Isolated surgical procedures such as sole synovialectomy of the toe joints or tenosynovialectomies of the flexor and extensor tendons are rarely indicated. Similarly, isolated bursitis at the 1st ray and plantar over metatarsal heads II to V is often combined with other procedures. Rheumatoid nodules occur much less frequently on feet than on upper extremities. Rheumatoid nodule excision should be performed only in cases of mechanically troublesome nodules, as recurrences can often occur. As a result of the significant improvement in basic medical therapy in recent years, shoe-related care and the patient’s understandably reticent willingness to undergo surgery, multiple advanced joint destructions with malpositions in the forefoot often become apparent, requiring complex surgical therapy. Resection arthroplasty of the MTP joints according to Hoffmann/Tillmann (MT II to V) and Hueter/Mayo (MT I) has been the method of choice for many decades and can be described as the “gold standard” in rheumatism surgery. [7,8] (Figs. 5 and 6). Destruction of the forefoot causes the metatarsal heads to protrude plantarward and results in complete depletion of the fat pad. In the original method according to Hoffmann/Tillmann and Hueter/Mayo, all MT heads are resected so that rolling of the foot is possible again without pain.

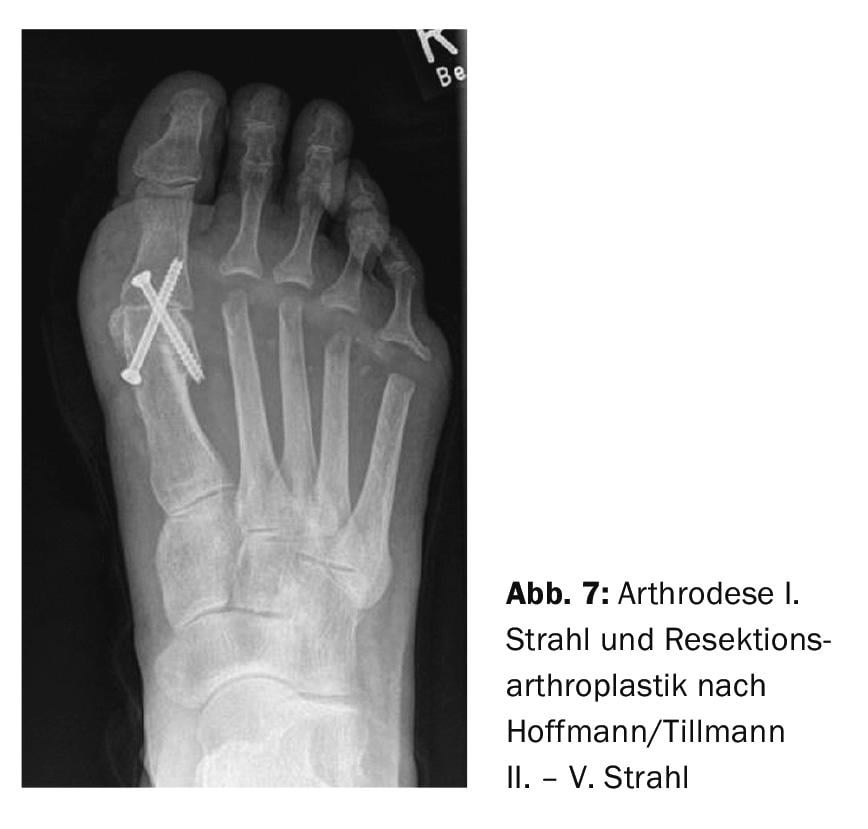

During subcapital resection of all MT heads of the 1. to 5. beam, it must be ensured that the load capacity of the 1st beam is preserved. Otherwise, if the resection is too extensive, the procedure leads to functional amputation of the forefoot. Since especially for the rolling behavior the load capacity of the 1st beam is of decisive importance, the identical technique according to Hoffmann/Tillmann is meanwhile used on the 2nd to 5th rays combined with arthrodesis of the metatarsophalangeal joint of the big toe (Fig. 7).

Arthrodesis leads to a secure alignment of the 1st ray with good ground contact and thus improves the load bearing capacity, which is important for rolling. An alternative to metatarsophalangeal joint arthrodesis is endoprosthesis implantation using Swanson Silastic Spacers. This avoids shortening of the 1st ray and even if the spacer fails, fibrinous capsule stabilization usually occurs. An alternative with a similar principle are the Scaffold polylactide spacers developed in recent years. In contrast, metatarsophalangeal joint arthroplasties made of metal or ceramic are not used in rheumatoid feet because of the osteoporotic conditions that often occur close to the joint.

Modern drug therapies (biologics) seem to improve the course of the disease with less destruction, so that joint-preserving techniques are increasingly used in rheumatoid surgery. Thus, the scarf and chevron osteotomy of the great toe, which have proven successful in hallux valgus surgery, as well as the Weil osteotomy of the 2nd to 5th metatarsophalangeal joint are now also performed (Figs. 8 and 9).

It is always important to combine joint-preserving surgery with joint synovialectomy, if necessary. also with extensor tendon extension for plantarization of the often dorsally fixed 2nd to 5th toe. To stabilize the positioning and axis alignment of the toes, if necessary. temporary axial Kirschner wire fixation is also useful. The patient must be informed that – due to the systemic disease and the progression of joint destruction – joint-preserving interventions often require revision and resection arthroplasty in later years.

Another little-known procedure in rheumatoid forefoot surgery is resection arthroplasty at MTP II to V according to Stainsby. In contrast to the resection arthroplasty according to Hoffmann/Tillmann, the metatarsal heads are preserved and instead the base of the proximal phalanx is resected with joint synovectomy and transposition of the proximally separated extensor tendon onto the plantar plate or onto the flexor tendon at the level of the joint space. With this surgical technique, there is not yet sufficient experience for the rheumatoid foot. The disadvantage, however, is certainly on the one hand the retention of the metatarsal heads as the disease progresses, and on the other hand the severing of the extensor tendons, which no longer allow active lifting of the toes.

Postoperatively, all forefoot corrections are followed by the application of a redressing compression bandage for 2 to 3 days with decongestant measures and elevation of the foot. This is followed by further redressing dressings until suture removal. The temporary Kirschner wires inserted for axial alignment of the toes are removed after 6 weeks. During this time, the patient is mobilized with the help of a bandage shoe or a forefoot relief shoe. Overall, a splint fitting or bandages must be worn for 3 months to stabilize the forefoot corrections.

Conclusion

Although rheumatoid arthritis can be effectively treated at an early stage with efficient, modern basic medical treatment, there is still considerable destruction of certain joints in the course of the disease. The forefoot is particularly frequently affected. After exhausting all conservative, especially shoe-related, treatment, differentiated surgical measures should be considered. There are no uniform standards for the surgical treatment of the rheumatoid forefoot due to the different patterns of involvement. Based on many years of experience, the combination between stable 1st ray with arthrodesis of the metatarsophalangeal joint of the big toe and the gentle resection arthroplasty of the remaining metatarsophalangeal joints still appears to be the “gold standard”. Joint-preserving techniques of general foot surgery are recommended if the pattern of involvement is only slight, but especially in younger patients.

The ultimate goal of all therapeutic measures is the satisfaction of the rheumatic patient with preservation of mobility and quality of life.

Take-Home Messages

- Think rheumatism if there are multiple painful swollen joints in the hands and feet with morning stiffness for weeks and months with elevated inflammation levels, ESR and CRP.

- Early treatment of the rheumatoid foot with insoles and shoe fitting in collaboration with an orthopedic shoemaker to maintain the patient’s mobility and avoid surgery.

- Regular clinical and radiological joint checks in order to detect progressive changes and perform surgery at an early stage, if necessary. to intervene in a joint-preserving manner.

- In the case of multiple joint surgery, the strategy is usually from the trunk (shoulder, hip) to the periphery (elbow, hand/knee, foot).

Literature:

- Droste U: Differential diagnosis and clinic of rheumatoid arthritis, Praktische Rheumaorthopädie, ed. Thabe H. Chapmann & Hall 1997; 13-15.

- Greitemann B, Kemmerling M: Orthopädietechnik und orthopädietechnische Versorgung, Orthopädische Rheumatologie, ed. Rehart S. Sell, S. Thieme 2016; 123-125.

- Henniger M, Rehart S: Forefoot. Orthopedic Rheumatology, ed. Rehart S, Sell S. Thieme 2016; 325-334.

- Kuipers JG, Köhler L: Rheumatoid arthritis symptoms and differential diagnosis, Orthopedic Rheumatology, ed. Rehart S, Sell S. Thieme 2016; 20-22.

- Nawaczenski DA, Saltzman CL, Cook TM: The effect of foot structure on the three-dimensonal kinematic coupling behavior of the leg and rear foot. Phys. Ther 1998; 78 (4): 404-416.

- Stinus H: Orthopaedic care strategies of the rheumatoid foot, Foot and Ankle 2012; 10: 242-246.

- Tillmann K. Der rheumatische Fuss und seine Behandlung, Enke 1977.

- Tillmann K: Forefoot correction, Orthopaedics 1973; 2: 99-100.

- Wolfram U: The Ankle Joints – Pathophysiology, Pract. Rheumatic Orthopaedics, ed. Thabe H. Chapmann & Hall, 264-265.

- Wolfram U: The forefoot – pathophysiology, Clin. Image, Pract. Rheumatic Orthopaedics, ed. Thabe H. Chapmann & Hall, 280-283.

InFo PAIN & GERIATURE 2019; 1(1): 16-20.