Opioids are an important component of therapy for severe chronic pain. Despite their good efficacy and lack of toxicity to internal organs, treatment is often discontinued due to undesirable side effects. One of these is opioid-induced constipation (OIC), which is often difficult to treat. In laxative-refractory OIC, µ-opioid receptor antagonists (“peripherally acting µ-opioid receptor antagonists”, PAMORAs) may provide relief.

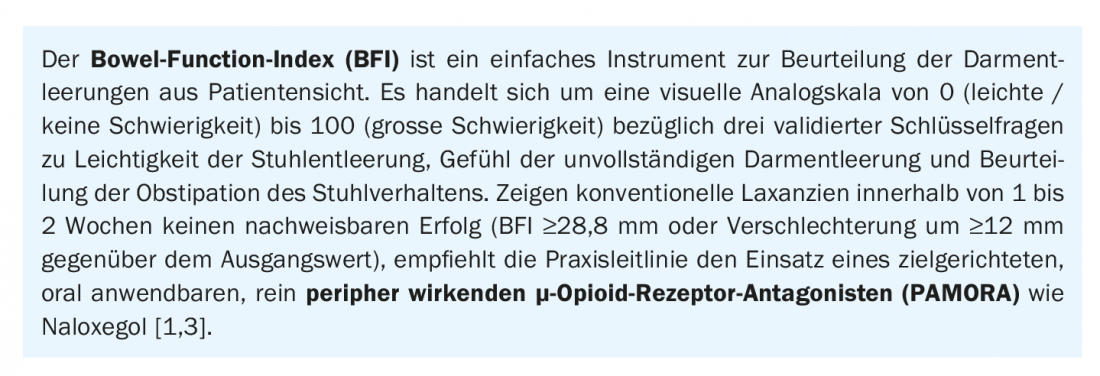

Many patients rely on potent opioids for effective pain relief, but it is not uncommon to experience gastrointestinal side effects. Opioid-induced constipation (OIC) is a common side effect of opioid therapy. It is a particular form of constipation caused by the activation of µ-opioid receptors in the intestine. The affected patients suffer from a significant reduction in quality of life. Low stool frequency (<3x/week), hard stools, inappetence, nausea, vomiting and flatulence are among the typical symptoms of OIC. These are so distressing for many patients that they reduce their opioid dose or even discontinue therapy altogether. To improve patient quality of life and maintain adequate analgesia, early diagnosis of OIC is central. This requires a careful stool anamnesis and active inquiries on the part of the physician. The practical recommendations for action of the German Society for Pain Medicine appeared in 2019 in an updated version [1]. This proposed the use of the Bowel Function Index (BFI) as a simple tool to assess bowel function from the patient’s perspective (box).

Macrogol as first-choice laxative

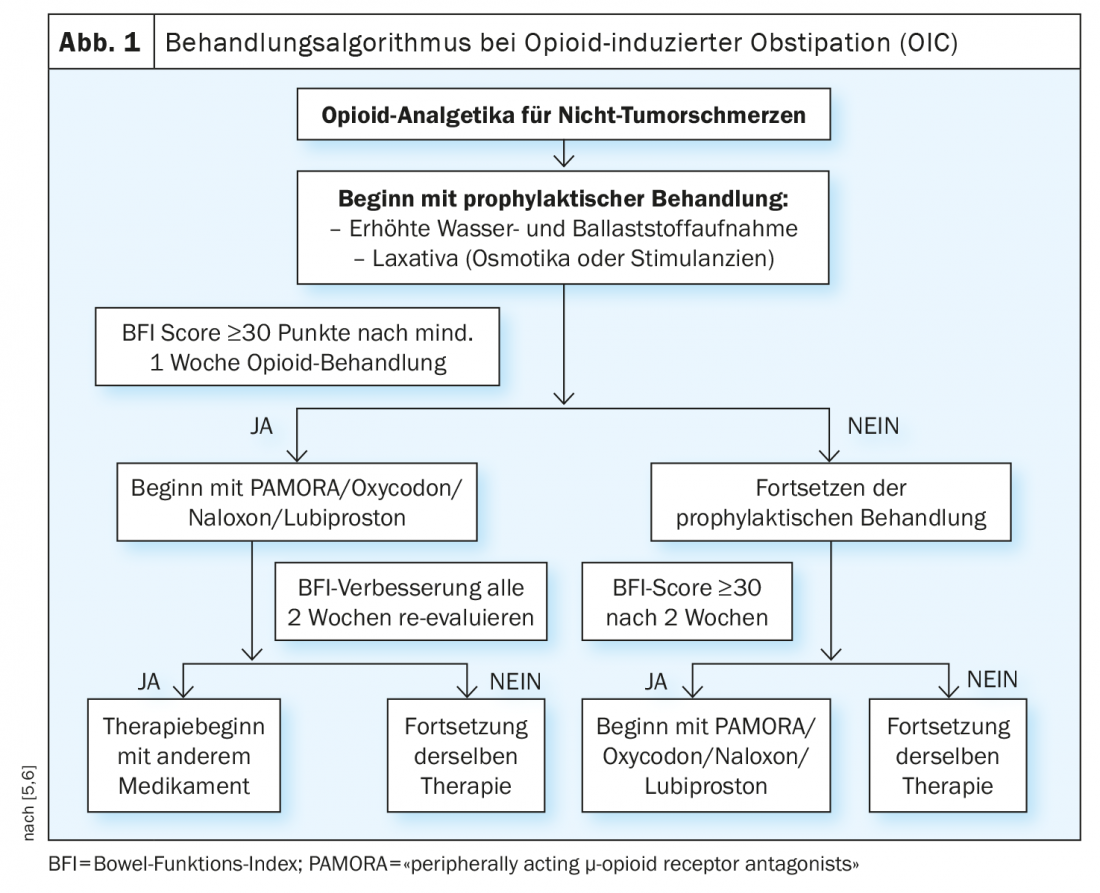

Conventional laxatives still count internationally as first-line therapy for the treatment of OIC. However, these do not bring satisfactory treatment success in about half of those affected. This can be explained by the nonspecific mechanism of action, which in OIC is outweighed by the specific effects of opioids on the autonomic enteric nervous system. The guideline recommends that patients be prescribed macrogol (polyethylene glycol) along with opioids as a concomitant medication early in therapy. In a randomized trial, macrogol was shown to be superior to placebo in the treatment of methadone-induced constipation [2]. Other conventional laxatives used in OIC include bisacodyl, sodium picosulfate, and senna preparations. Response to a laxative varies interindividually. If the use of an active substance – if necessary in an adjusted dosage – proves not to be effective, it is advisable to switch to a different class of active substance.

Treat laxative-refractory OIC with PAMORA.

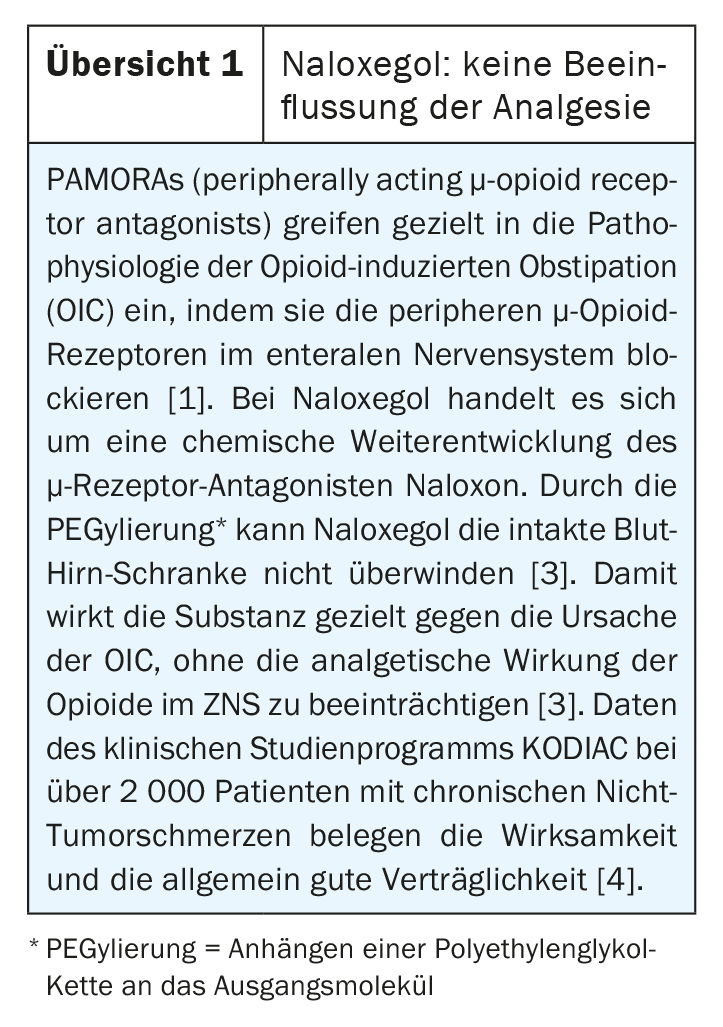

If conventional laxatives do not result in significant improvement in OIC (e.g., BFI >28.8 mm VAS, and/or decrease <12 mmVAS, etc.), the guideline suggests treatment with a peripherally acting µ-opioid receptor antagonist (PAMORAs). PAMORAs such as naloxegol, methylnaltrexone and naldemedine significantly alleviate the symptoms of OIC according to placebo-controlled clinical studies and were found to be well tolerated. PAMORAs exert their effect by blocking the peripheral µ-opioid receptors. As PAMORAs do not cross the (intact) blood-liquor barrier due to their molecular structure, there are no central effects, so that there is no measurable impairment of the analgesic effect of the opioids, as has been demonstrated in clinical studies [1]. “The extent to which peripherally mediated analgesic effects of opioids that are necessary in specific individual cases can nevertheless be prevented by PAMORA is currently under discussion,” the guideline authors said. The risk is low, but cannot be completely ruled out, he said.

In individual cases in which monotherapy is insufficiently effective and if the use of peripherally acting µ-opioid receptor antagonists (PAMORAs) is not an option, a combination of preparations with different modes of action may be considered for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation. Good combinations are, for example, macrogol (polyethylene glycol) and the hydragogic laxative bisacodyl.

Literature:

- DGS Practice Guideline: Opioid-Induced Constipation, 2019, https://dgs-praxisleitlinien.de/opioidinduzierte-obstipation (last accessed May 31, 2021).

- Freedman MD, et al: Tolerance and efficacy of polyethylene glycol 3350/electrolyte solution versus lactulose in relieving opiate-induced constipation: a double-blinded placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Pharmacol 1997; 37(10): 904-907.

- Swissmedic: Expert information Moventig®; www.swissmedicinfo.ch (last accessed 31.05.2021)

- Chey WD, et al: Naloxegol for opioid-induced constipation in patients with noncancer pain. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 2387-2396.

- Nelson AD, Camilleri M. Opioid-induced constipation: advances and clinical guidance. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2016; 7(2): 121-134.

- Argoff CE, et al: Consensus Recommendations on Initiating Prescription Therapies for Opioid-Induced Constipation. Pain Med 2015; 16(12): 2324-2337.

Further reading:

- Farmer AD, et al: Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018; 3(3): 203-212.

- Murphy JA, Sheridan EA: Ann Pharmacotherapy 2018; 52(4): 370-379.

- Sridharan K, Sivaramakrishnan G: J Pain and Symptom Manage 2018; 55: 468-479.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(6): 22-24