The earliest possible detection of cognitive disorders makes a lot of sense: on the one hand, treatable causes can be discovered, and on the other hand, those affected still have the opportunity to help plan their personal future. Various tools exist for the general practitioner’s office to determine cognitive impairments – the “BrainCheck” is now also available. In the case of people with a high level of education, it must be taken into account that they usually have a large cognitive reserve and therefore limitations in mental performance often only become manifest at an advanced stage of a disease.

Age is the most important risk factor for the development of cognitive disorders. Therefore, due to the rapidly increasing proportion of elderly people in the world population, an equally increasing number of people with brain disorders can be expected. Although recent data from England, Sweden, and the Netherlands indicate that the expected number of dementia patients will not be quite as high as previously expected because the health of the older population will be better than predicted. Nevertheless, cognitive impairment remains a highly relevant and certainly growing health problem.

Why early diagnostics?

For a number of reasons, the earliest possible detection of changes in cognitive performance is indicated. On the one hand, about 10% of the causes are causally treatable and – at least partially – reversible. This concerns, for example, normal pressure hydrocephalus, vitamin B12 deficiency, pronounced affective disorders, or obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. The symptoms of these disorders can usually improve significantly with successful therapy. However, even when cognitive disorders are not causally treatable, effective symptomatic therapies are available. For example, the effects of antidementia drugs – acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine – have been repeatedly demonstrated in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, and Parkinson’s-associated dementia. The achievable delay in deterioration brings a gain in quality of life for those affected and their social environment and also helps to reduce care costs in the long term.

The early identification of cognitive impairments and their differential diagnostic classification also serve to avoid treatment errors. For example, in the early stages of dementia with Lewy bodies, treatment with such substances should be avoided if possible because of increased neuroleptic sensitivity.

The goal of identifying cognitive change is to stabilize – and in some cases even slightly improve – symptomatology. If this is achieved at the earliest possible stage of the disease, those affected still have the opportunity to help plan their personal future, such as their future living or care situation and the writing of a living will or testament. Since cognitive symptoms are usually very stressful not only for the patients themselves but also for their relatives, early recognition and correct differential diagnostic classification allow targeted counseling and support of the social environment as well.

Screening or “case finding”?

So what is a useful way to detect changes in cognition and, if necessary, behavior at an early stage? In an analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, Lin et al. concluded that there is insufficient evidence for or against the benefits of population-based routine screening of older people for cognitive symptoms [1]. In contrast, the American Alzheimer’s Association, in its recommendations for the detection of cognitive symptoms during the annual health examination, indicates that action should be taken in primary care practice when relevant initial evidence of cognitive changes is present, this screening being referred to more narrowly as “case finding” [2]. The indication for “case finding” is always given when patients or relatives report corresponding problems or when one notices corresponding behavior in the daily routine of a doctor’s practice. These include:

- Mental symptoms, e.g., decrease in memory, planning ability, interest, drive

- Behavioral changes, e.g., distancing, irritability, social withdrawal.

- Observations in the office, e.g., missing doctor’s appointments multiple times, inappropriate clothing.

Case-finding in the family practice

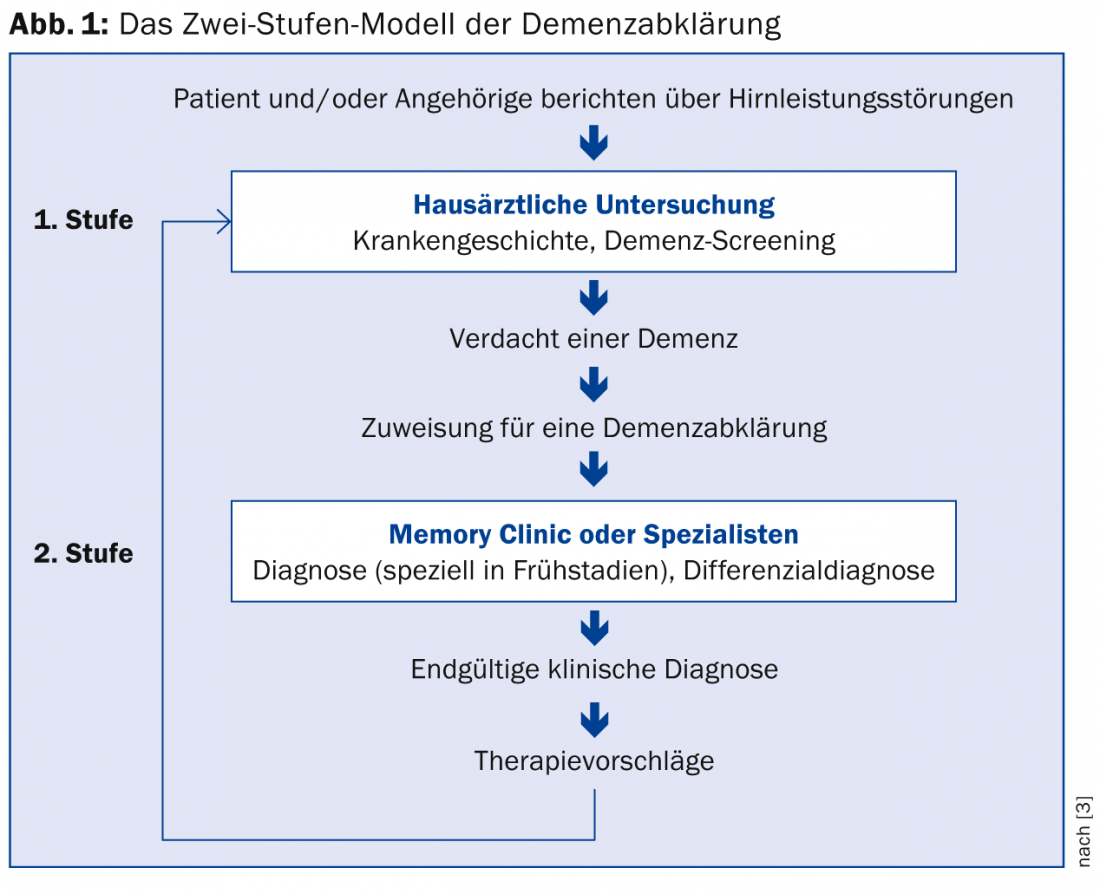

The primary care physician has a very significant role in detecting cognitive symptoms. This is expressed in the so-called two-stage model, which is widely used in Switzerland (Fig. 1) [3]. The Swiss Consensus Criteria for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Dementia emphasize that the assessment by the general practitioner and, if necessary, a subsequent interdisciplinary examination at a memory clinic provide clarity about the extent and cause of mental disorders, so that adequate pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions can be established [4].

For primary care, there is a whole range of screening or Case-finding tools available to identify cognitive deficits. These must then be clarified in a more comprehensive and differentiated manner in a next step. However, it must be emphasized: Screening procedures should not, cannot and must not be used to make diagnoses – under any conditions!

In addition to the best-known tool, the Mini Mental Status (MMS), the clock test or increasingly the MoCA test (Montreal Cognitive Assessment; www.mocatest.org) as well as a whole range of other procedures are used.

In family practice, however, the time required to assess aspects of mental performance is a critical factor, as consultations often involve the assessment of many medical parameters – and this with very limited time resources. In addition, the use of such short tests is often experienced by physicians and patients as unpleasant and confrontational due to the nature of the questions and is therefore refrained from in many cases. In the case of MMS, there is also the fact that a copyright applies to this process and that use is subject to a charge.

So what can help to decide in a time-efficient manner in primary care practice whether a patient’s cognitive performance has changed such that it requires further evaluation, or whether observational waiting is indicated? The proposal by Cordell et al. provides for three sources of standardized information to be obtained at the first indication of cognitive symptoms: Interviewing the patient, a short test, and interviewing relatives.

Testing by means of “BrainCheck

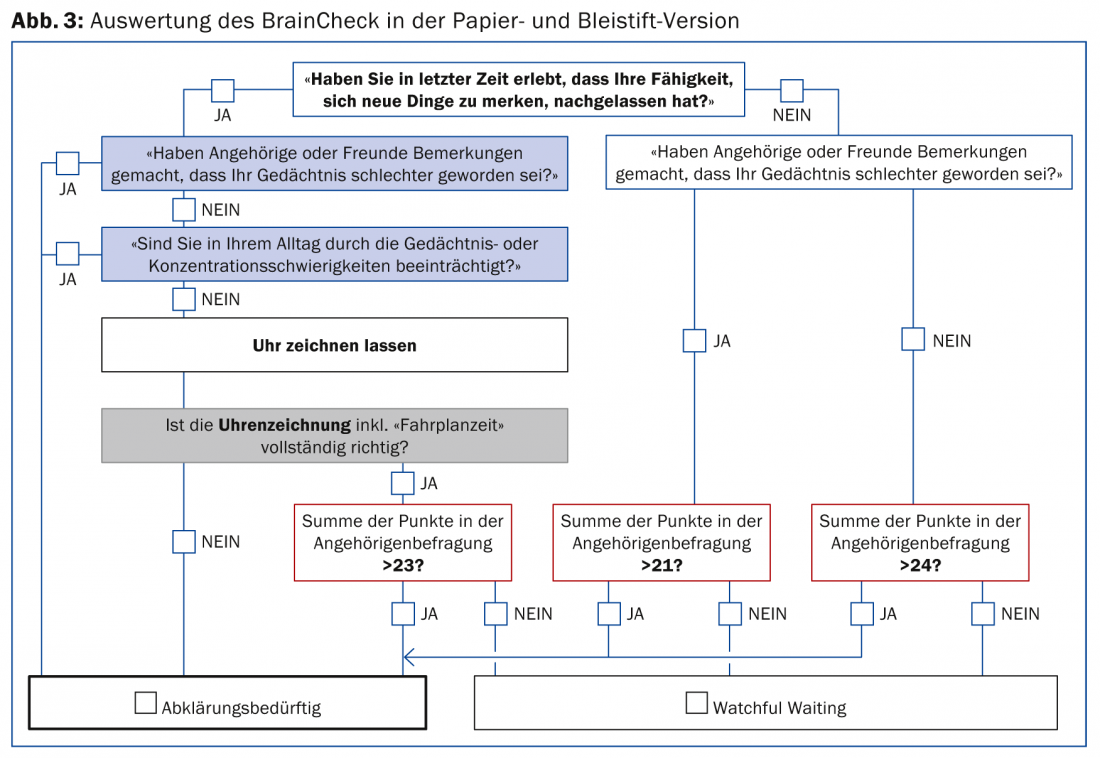

The realization of a short instrument with this combination of information was already the aim of a multi-center study of several memory clinics in Switzerland before the publication of these recommendations. “BrainCheck” was developed, a short tool lasting about five minutes, which – when used in GP practice – gives an indication of how to proceed in a meaningful way [5]. In the case of a conspicuous result, an in-depth, usually interdisciplinary clarification should be carried out; in the case of an inconspicuous result, observational waiting is appropriate, if necessary with repetition of the examination in 6-12 months.

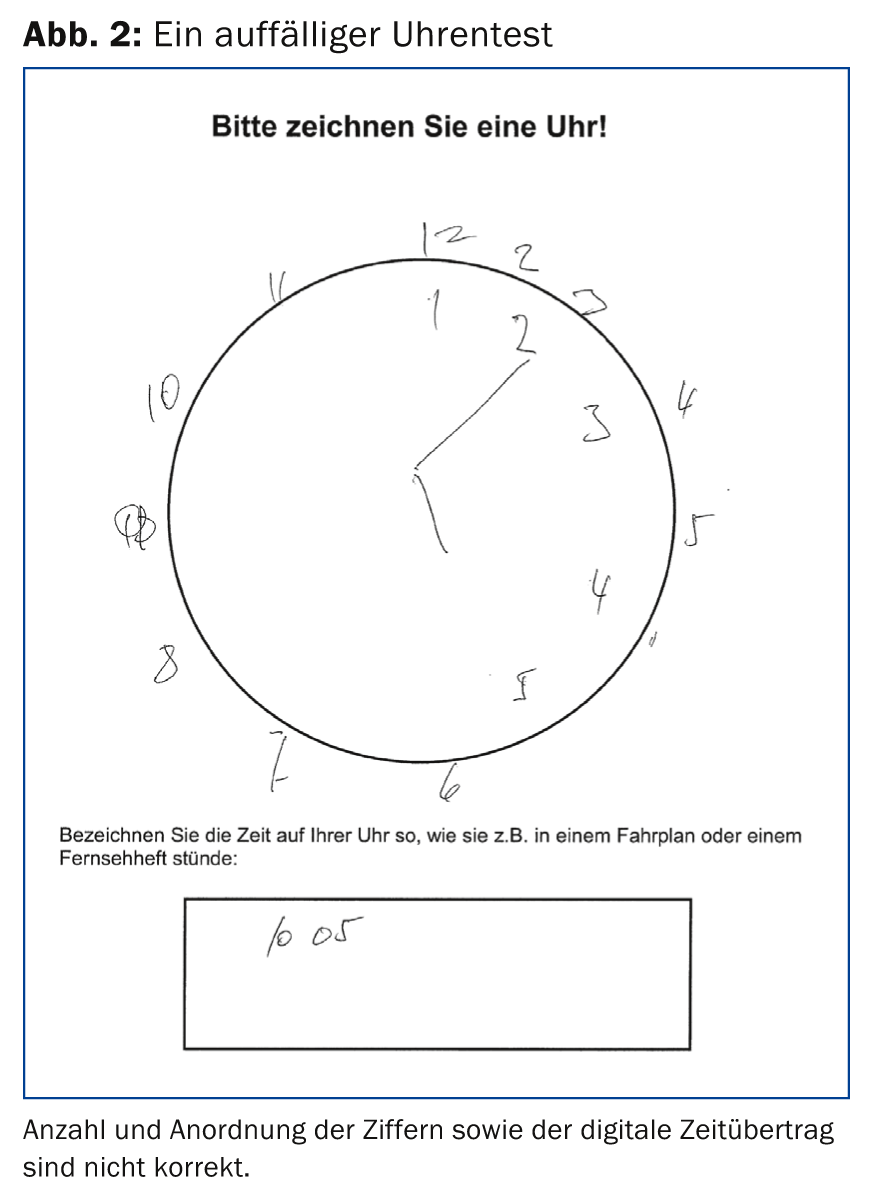

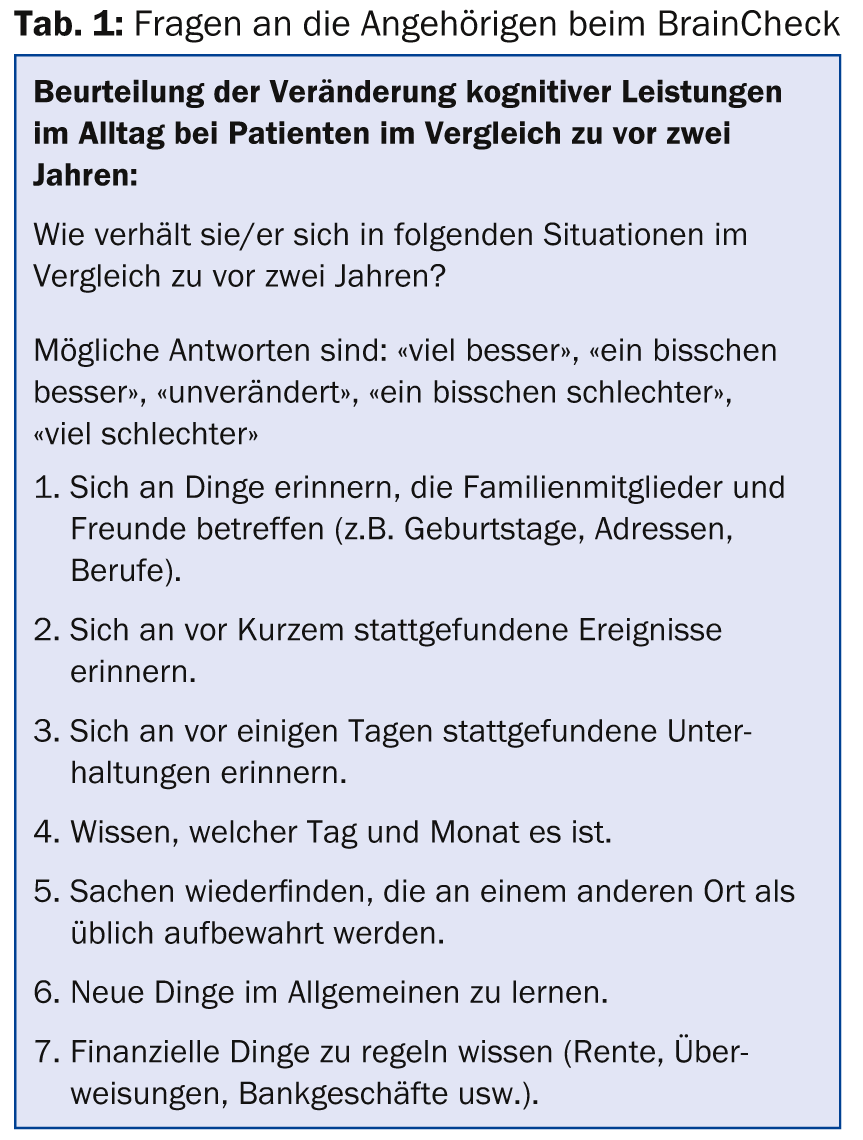

BrainCheck consists of (a) Three questions to the patient, (b) the clock test (Fig. 2) and (c) the interview with a relative regarding changes in the patient within the last two years (Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly, IQCODE) (Table 1) [6,7].

After development of the BrainCheck, its applicability by primary care physicians was tested in a preliminary study. It could then be shown in a further study that with the empirically derived evaluation algorithm (Fig. 3) it is possible to correctly classify individuals from a group of healthy individuals and a group of patients (with mild cognitive impairment, mild Alzheimer’s dementia or major depression) as “normal” or “requiring clarification” in 89% of the cases.

The time required for implementation and evaluation is only a few minutes, which is significantly less than that of other screening tools (the questionnaire can easily be completed by the family member in the waiting room).

Cognitive reserve

Early detection of mental symptoms is not useful only when the criteria for a dementia syndrome are met and there is an indication for drug treatment. A particular challenge arises when the earliest cognitive changes are to be detected in patients with (very) high baseline intellectual levels. It may be significant to perform a more detailed workup even if results of simple short procedures are unremarkable but patients complain of changes in performance.

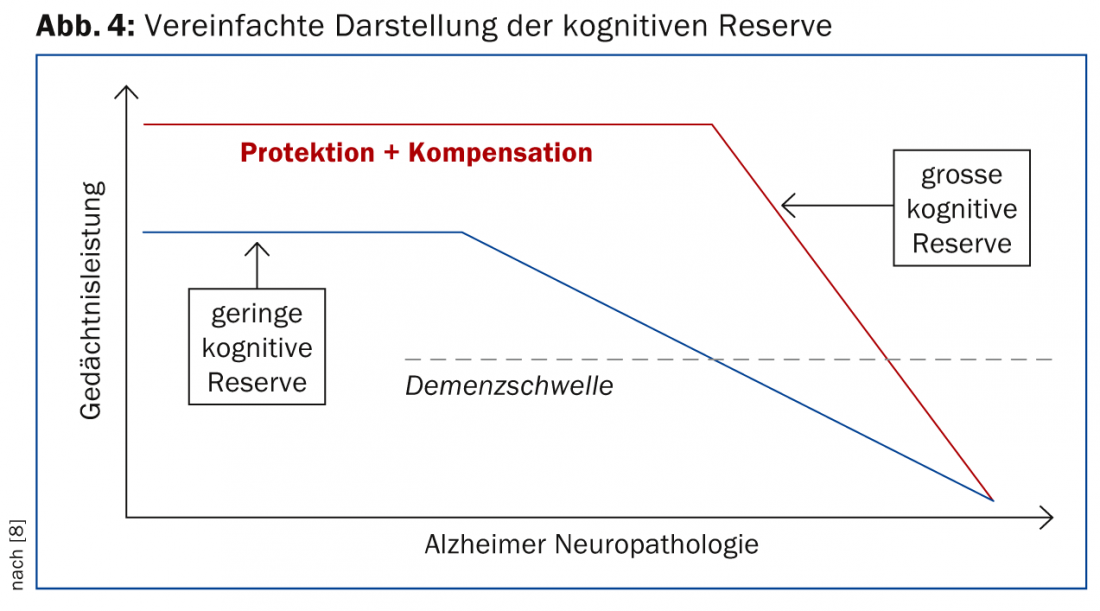

The concept of cognitive reserve assumes that in the presence of a pathological brain process, cognitive networks can be used more flexibly and efficiently in the accomplishment of tasks when people have higher educational and professional qualifications and are mentally active – even if the higher mental activity has occurred only in later stages of life (Fig. 4) [8].

This concept has important significance not only for the diagnostic process, but also for patient care. When brain pathology begins to impair performance in a person with high cognitive reserve, the decline will be more rapid because the extent of the pathology is already very pronounced by that time. This requires closer monitoring so that therapy can be adjusted in a timely manner.

Risk factor therapy

Although causal evidence has not yet been established, epidemiological studies indicate that consistent treatment of potentially modifiable risk factors could significantly reduce the incidence of AD [9]. In addition to improved access to education, these include reducing vascular risk factors – physical inactivity, hypertension, smoking, obesity, diabetes – and depression.

At this year’s Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) in Copenhagen, results of several studies were presented in which the risk factors were countered by means of multimodal, preferably individualized treatment approaches. The recommendations derived from these programs include measures to increase physical and also social activities, healthy eating, and psychological well-being. Although further robust data are needed to demonstrate robust effects, it is clear that only early detection of cognitive changes allows for – then intensified – early intervention, even if no cure for certain cognitive impairments is currently possible. The data on cognitive reserve should be reason to give increasing cognitively beneficial activities an important priority in the future. In addition, it remains clear that the development of better therapeutic options for brain disorders in the elderly must be prioritized in light of demographic trends.

Conclusion for practice

- Early identification of cognitive symptoms is a prerequisite for individualized treatment strategies to maintain and improve the quality of life of those affected and their social environment.

- Many causes of cognitive deficits are not curable, but treatable. This treatment should be done as early as possible.

- Family medicine has a central role in identifying disorders of cognition and behavior.

- Screening procedures do not provide diagnoses, but help to decide how to proceed.

- The “BrainCheck” tool is short, less confrontational, incorporates information from relatives, is easy to evaluate, and achieves a very high rate of correct decisions.

- Non-pharmacological treatment approaches to reduce risk factors must be given greater emphasis in the immediate future.

Dr. Michael Ehrensperger

Literature:

- Lin JS, et al: Screening for Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults: A Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2013; 159: 601-612.

- Cordell CB, et al: Alzheimer’s Association recommendations for operationalizing the detection of cognitive impairment during the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit in a primary care setting. Alzheimers Dement 2013; 9: 141-150.

- Stähelin HB, et al: Early diagnosis of dementia via a two-step screening and diagnostic procedure. Int Psychogeriatr 1997; 9(Suppl. 1): 123.

- Monsch AU, et al: Consensus 2012 on diagnosis and therapy of dementia patients in Switzerland. Praxis 2012; 101(19): 1239-1249.

- Ehrensperger MM, et al: BrainCheck – a very brief tool to detect incipient cognitive decline: optimized case-finding combining patient- and informant-based data. Alz Res Ther 2014; 6: 69. doi:10.1186/s13195-014-0069-y.

- Jorm AF, et al: Assessment of cognitive decline in dementia by informant. questionnaire. Int J Geriatr Psychiatr 1989; 4: 35-39.

- Ehrensperger MM, et al: Screening properties of the German IQCODE with a two-year time frame in MCI and early Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr 2010; 22(1): 91-100.

- Stern Y: Cognitive reserve. Neuropsychologia 2009; 47: 2015-2028.

- Norton S, et al: Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: an analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol 2014; 13: 788-794.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(1): 30-35