The symptoms of hyponatremia vary from mild to life-threatening. In recent years, therapeutic options for the treatment of hyponatremia have expanded. The therapeutic approach is based primarily on the severity of symptoms. It is important to identify and eliminate remediable causes. Short- and long-term treatment strategies should be individualized.

Whether in the ICU, emergency department, or family practice, hyponatremia is the most common electrolyte and water balance disorder. It is a heterogeneous and often multifactorial disorder [1]. According to the current European guideline, a serum sodium level below 135 mmol/l is considered hyponatremia, distinguishing between a mild (130-135 mmol/l), a moderate (<130 mmol/l), and a severe (<120 mmol/l) form [2]. While mild and moderate symptoms manifest as depression or mild gait unsteadiness, respectively, nausea, confusion, or gait disturbance, severe hyponatremia is associated with significantly increased morbidity and mortality [4]. Seizures and coma may occur, and the tendency to fall and fracture rate are increased. Therefore, chronic hyponatremia is of particular importance in geriatrics [3].

ADH regulates water and electrolyte balance

Hyponatremia is usually not due to sodium deficiency but primarily to a disturbance in the body’s fluid balance [4]. By determining the antidiuretic hormone in the blood (ADH or vasopressin), conclusions can be drawn about a disturbance in the body’s fluid balance. Hyponatremia is almost always also associated with impaired ADH secretion [4]. ADH is formed in the hypothalamus, stored in the pituitary gland and released from there into the blood. It regulates water and electrolyte balance in the body, acting mainly on the kidneys. There are many causes of hyponatremia, and the risk increases with age [4]. Certain medications, concomitant conditions, and diseases are trigger factors. Careful differential diagnostic considerations are an important basis for choosing the appropriate treatment strategy [5]. In addition to causal therapy, these include administration of fluid volume, fluid restriction, or delivery of hypertonic fluid. In addition, vaptans – AVP receptor 2 antagonists – are increasingly used to treat chronic hyponatremia [5].

Differentially examine for endocrine causes

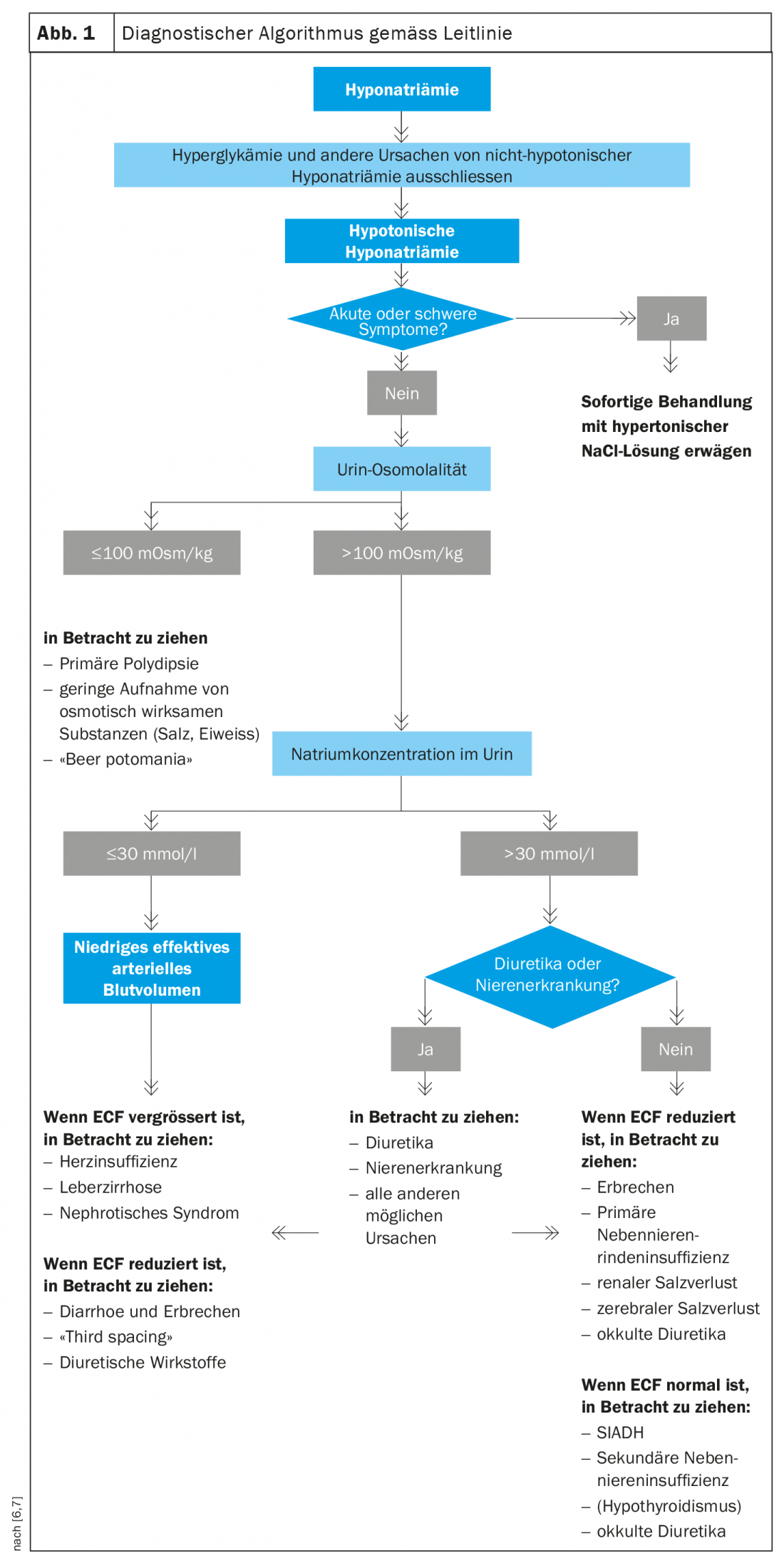

As part of the diagnostic workup (Fig. 1), urine sodium, plasma osmolality, and urine osmolality should be measured first after determining volume status. The latter serves to exclude primary polydipsia. Endocrine conditions that can lead to normovolemic hyponatremia include hypothyroidism and secondary adrenal insufficiency [4]. Primary adrenal insufficiency leads to hypovolemic hyponatremia due to aldosterone deficiency (renal sodium loss). If endocrine causes of hyponatremia can be excluded, further differential diagnosis can be made in the presence of syndrome of inadequate ADH secretion (SIADH). Malignant tumors, neurological diseases, drugs or pulmonary diseases are also possible causes of hyponatremia.

Syndrome of inadequate ADH secretion (SIADH)

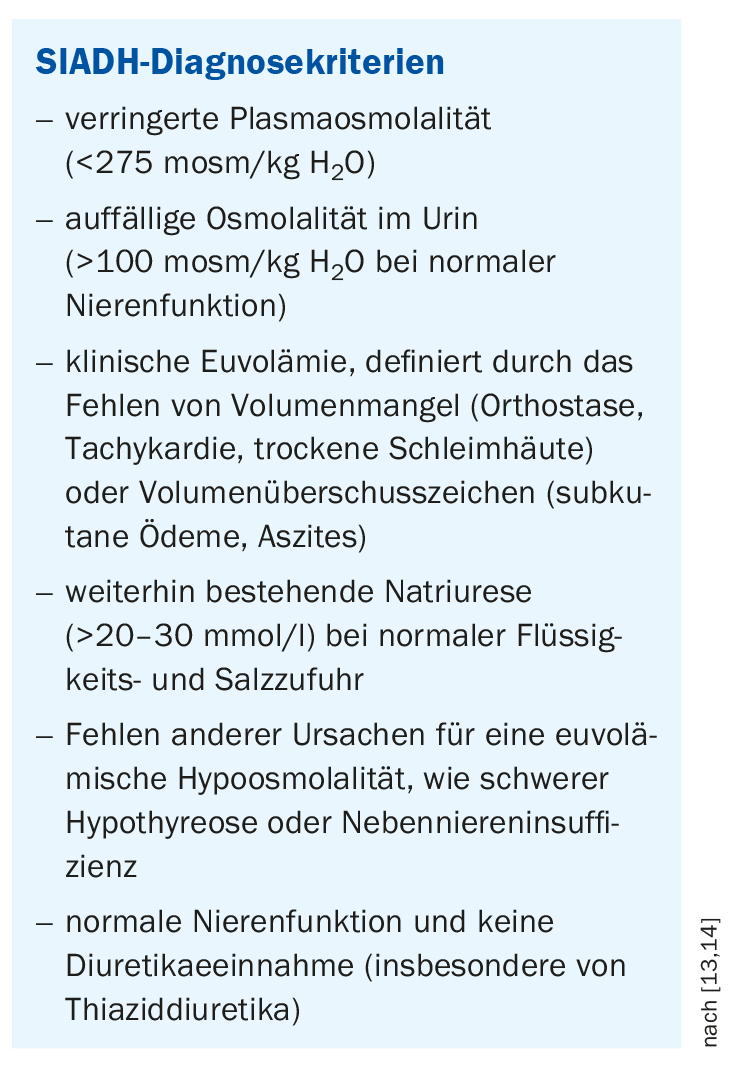

SIADH, also known as Schwartz-Bartter syndrome, is the most common form of hyponatremia. Due to an inadequately high release of ADH in the pituitary gland in relation to the osmolality of the blood plasma and the arterial volume ratios, too little water is excreted by the kidneys. This leads to a relative water excess and compensatory increased renal sodium excretion. [12]. This can cause hyponatremia and thus promote a dementia-like syndrome or delirium [15]. SIADH is relatively common in the elderly and in hospitalized individuals and can be identified by certain criteria (box). SIADH can occur when vasopressin is produced outside the pituitary gland, as in some cancers, but also in severe and infectious diseases of the lung and central nervous system [12]. Other trigger factors that may be considered are severe pain, anesthesia, stress, and trauma. However, numerous drugs can also induce increased pituitary ADH release and thus SIADH (e.g., certain antiepileptic drugs, antidepressants, neuroleptics, chemotherapeutic agents).

Therapy depends on the severity of symptoms

In addition to treatment of the precipitating cause, therapy with hypertonic saline should be given in cases of severe symptoms of hyponatremia (e.g., seizures, coma). The extent and speed of NaCl infusion are critical issues regarding efficacy and safety. Compensating for hyponatremia too quickly can lead to pontine myelinolysis. In patients with moderate and severe hyponatremia, rapid intermittent bolus infusion is preferred over slow continuous. The results of the prospective, multicenter SALSA (Efficacy and Safety of Rapid Intermittent Correction Compared With Slow Continuous Correction With Hypertonic Saline in Patients With Moderately Severe or Severe Symptomatic Severe Hyponatremia) study support this [16]. Current guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hyponatremia recommend an i.v. infusion of 100 ml of 3% saline over 10 minutes, which may need to be repeated depending on symptoms [6,7].

In patients with confirmed SIADH, in whom easily remediable precipitating causes can be excluded, drinking restriction is recommended. However, according to a prospective randomized study published in 2020, this can only result in a small increase in serum sodium levels [8]. High urine osmolality was identified as a parameter for nonresponse to fluid restriction in a prospective study [9].

There are also drug treatment options – one active substance approved in Switzerland for several years is tolvaptan (Samsca®, Jinarc®) [10]. This vasopressin antagonist can be used in adults to treat hyponatremia secondary to SIADH [10]. Because a dose titration phase with close monitoring of serum sodium levels and volume status is necessary, treatment with tolvaptan must be initiated in the hospital. Tolvaptan blocks the action of vasopressin at the V2 receptor on the kidney. This results in pure water diuresis without simultaneous sodium and potassium excretion [11].

Congress: SGAIM Lausanne

Literature:

- Holland-Bill L, et al: Eur J Endocrinol 2015; 173: 71-81.

- Spasovski G, et al: Eur J Endocrinol 2014; 170: G1-47.

- Gankam Kengne F, et al: Mild hyponatremia and risk of fracture in the ambulatory elderly, QJM 2008; 101: 583-538.

- Drug Commission of the German Medical Association (AKDAE) 2016, www.akdae.de/fileadmin/user_upload/akdae/Arzneimitteltherapie/AVP/Artikel/201604/188.pdf (last accessed 21.07.2022).

- Fenske W, Christ-Crain M: Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2016; 141: 457-460.

- Spasovski G, et al: Eur J Endocrinol 2014; 170: G1-47.

- “How to: Assessment and Therapy of Hyponatremia”, SGAIM, 01.06.2022.

- Garrahy A, et al: J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020; 105(12):dgaa619.

- Winzeler B, et al: J Int Med 2016; 280: 609-617.

- Drug Information,www.swissmedicinfo.ch, (last accessed 07/21/2022).

- Schrier RW, et al: N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 2099-2112.

- Wishes F: Hyponatremia: sodium and water imbalance, www.pharmazeutische-zeitung.de/ausgabe-492017/natrium-und-wasser-im-ungleichgewicht, (last accessed 07/21/2022).

- Demars Y, et al: Swiss Med Forum 2019; 19(3536): 584-587, https://medicalforum.ch/de/detail/doi/smf.2019.08074, (last accessed 07/21/2022).

- Verbalis JG, et al: The American Journal of Medicine 2013;126(10): S1-42.

- Neuner-Jehle S, Senn O: Polypharmacy, 11/2021, Medix Guideline, www.hausarztmedizin.uzh (last accessed 07/21/2022).

- Baek SH, Kim S: Kidney Res Clin Pract 2020; 39(4): 504-506.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2022; 17(8): 24-26

CARDIOVASC 2022; 21(3): 36-37