In the case of the leading symptom of dizziness, a structured procedure incl. targeted questioning of the duration and frequency of episodes as well as provocation factors and a focused neuro-otological examination including the search for subtle oculomotor signs is essential. Identifying dangerous, potentially life-threatening causes is a priority. In acute vestibular syndrome, these are mainly vertebrobasilar ischemias, in episodic vestibular syndrome cardiac arrhythmias, and in chronic vestibular syndrome neoplasms. Additional examinations such as MRI, CT or vestibular testing are often of decisive help if used in a targeted manner. In addition to causal therapy measures, balance training (“vestibular physiotherapy”) has proven particularly effective for treatment.

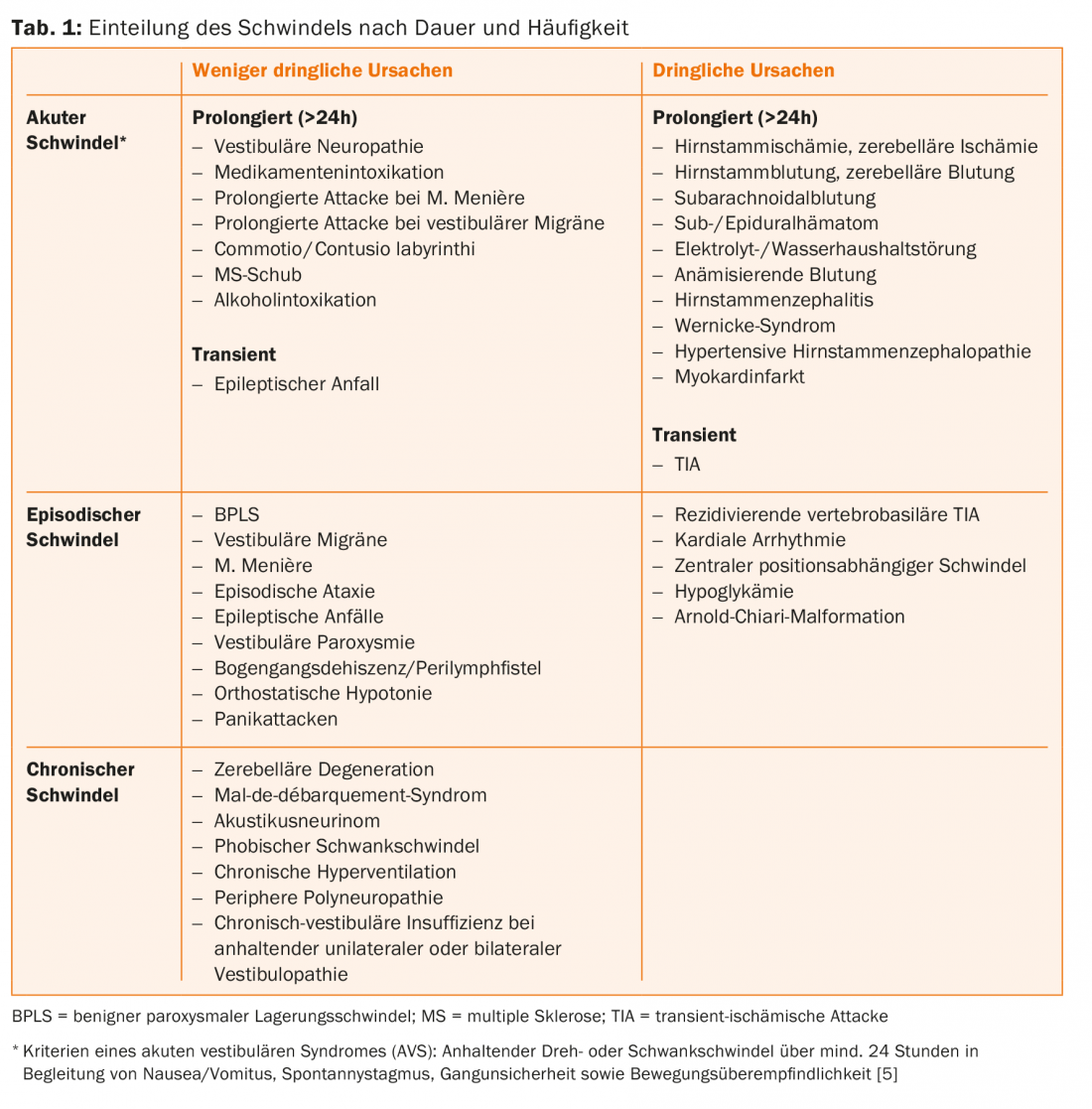

Dizziness is one of the most common leading symptoms and is present in 3-6% of all emergency consultations [1,2]. Because of the extremely broad differential diagnosis, clinicians from a wide variety of specialties are confronted with this symptom. Clear classification is complicated by the fact that no single cause accounts for more than 5-10% of all vertigo diagnoses [1] and terms such as spinning, staggering, or elevation vertigo are used differently. It is important to emphasize that a distinction between “dangerous” and “benign” vertigo, based on the type of vertigo, cannot be reliably made. On the one hand, because patients often do not describe their vertigo symptoms precisely [3], and on the other hand, because all forms of vertigo can have dangerous causes. In 10-15% of patients with leading symptoms of dizziness, there is a serious condition [1]. The initial assessment must prioritize the identification of patients who urgently require further diagnostic and therapeutic intervention (Table 1).

Medical history in patients with vertigo

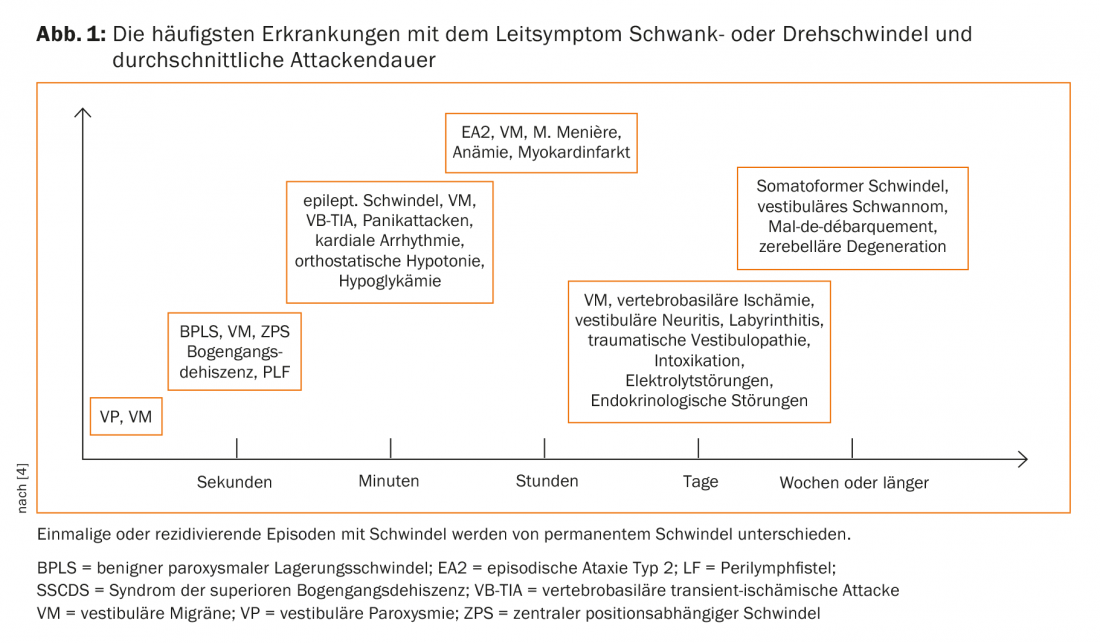

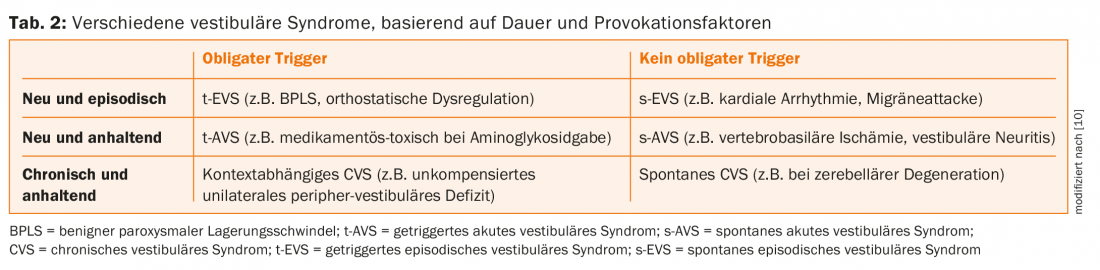

The history focuses on questions about the duration and frequency of attacks (Fig. 1, Tab. 2), their onset, accompanying symptoms, provoking factors, trauma, and medication.

An attack-like occurrence after changes in the position of the head (turning in bed, standing up/lying down, turning the gaze up/down) is indicative of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPLS), isolated occurrence after standing up quickly is indicative of orthostatic vertigo, and situational occurrence in busy places (e.g., department store, public places) is indicative of phobic vertigo. Head or neck injuries and manipulations (chiropractic treatment) should be specifically inquired about, as these can lead to vascular dissection. Each patient’s existing medication and recent dose adjustments should be collected. The range of causative drugs is long and includes neurodepressants (neuroleptics, antiepileptics, benzodiazepines, antidepressants), diuretics, and antihypertensives, among others.

Clinical examination

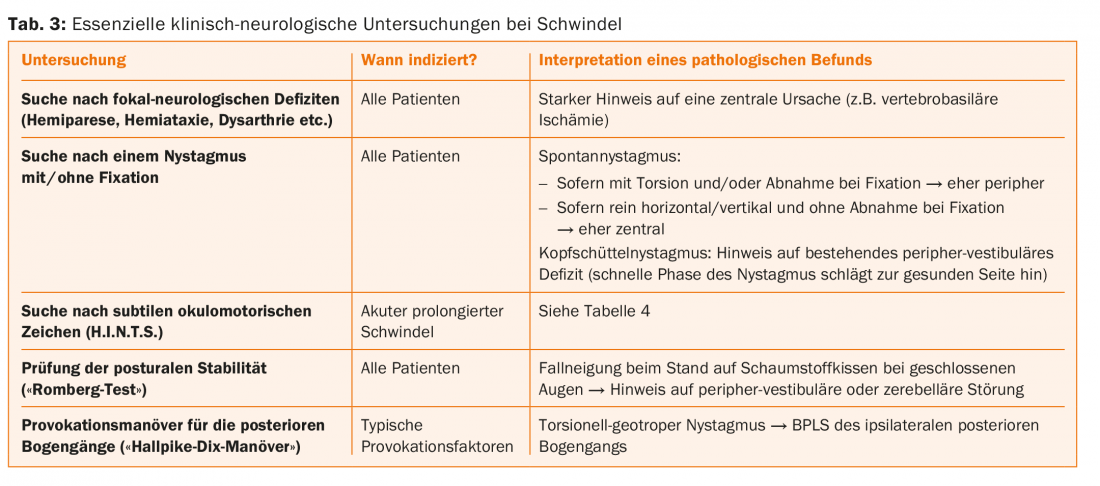

The clinical examination should include a specific neuro-otological examination (tab. 3) . It should be taken into account that even in the presence of a central cause, vertigo can occur in up to 50% of cases in isolation, i.e., without obvious focal neurological deficits [5].

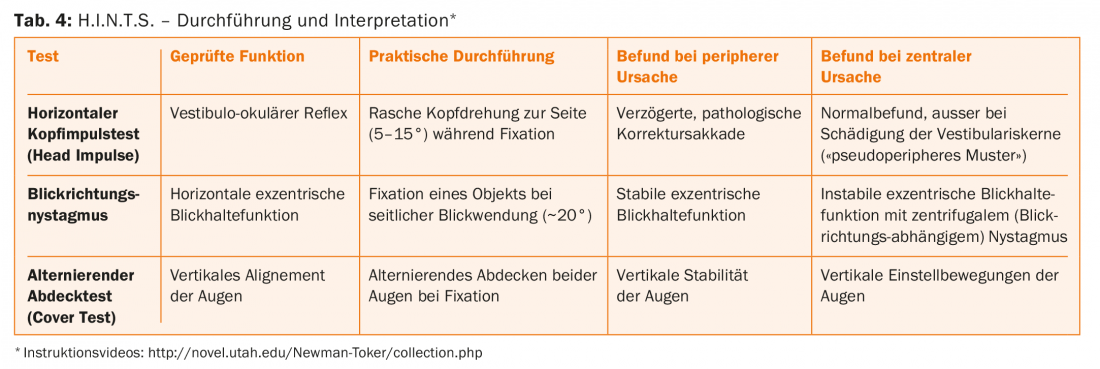

In this regard, the specific search for subtle oculomotor signs has proven helpful. This test includes three components, takes approximately five minutes, and can be performed at the patient’s bedside. It includes the head impulse test (“HeadImpulse”), the horizontal gaze turn (“Nystagmus“) and the alternating cover test (“Test of Skew“), resulting in the acronym H.I.N.T.S. (Tab. 4). This test battery can detect stroke in the patient with acute prolonged vertigo with higher sensitivity than an MRI performed early (i.e., within 24-48 hours) incl. Diffusion weighting (98% vs. 80%) [5].

If neuro-otologic examination is unproductive, non-neurologic causes should be considered. The most common internal causes included electrolyte/water balance disorders (5.6%), vasovagal syncope (6.6%), cardiac arrhythmias (3.2%), anemia (1.6%), and hypoglycemia (1.4%) [1].

Cerebral imaging

Diffusion-weighted MRI (DWI) is the imaging modality of choice for suspected vertebrobasilar ischemia, whereas CT is inferior in this setting because of its much lower sensitivity (approximately 40% vs. 80%). It is important to keep in mind that up to 20% of early MRI examinations (including DWI) may have a false-negative finding [5]. Accordingly, if clinically highly suspected, imaging should be repeated after three to ten days.

Peripheral-vestibular diagnostics

Nowadays, it is possible to measure the function of the arcades and otolith organs in detail. Here, the video head impulse test is becoming increasingly popular [6], as it allows quantitative assessment of all six arcades within ten minutes. The vestibular-evoked myogenic potentials (VEMPs) allow testing of the otolith organs: By means of short acoustic stimuli or vibrations, stimulation and derivation of the reflex muscle contractions of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (cervical VEMPs = sacculus test) resp. of the inferior oblique muscle (ocular VEMPs = utriculus test). VEMPs are more complex to perform and are therefore reserved for specialty clinics. Subjective visual vertical (SVV) also allows assessment of otolith function. Here, the patient is asked to set a line along the perceived perpendicular to the earth, which can also be done at the patient’s bedside with little effort (“bucket test”) [7].

First time acute vertigo

In acute dizziness, the primary concern is to distinguish potentially life-threatening conditions from benign causes. >If the constellation of an acute vestibular syndrome (AVS) is present, i.e., in addition to spinning or staggering vertigo, spontaneous nystagmus, nausea/vomiting, gait unsteadiness, and hypersensitivity to movement exist for 24 hours [5], neuro-otological causes should be sought. In addition to clinical examinations, H.I.N.T.S. and MRI play an important role. In contrast to the most common peripheral cause of AVS – vestibular neuropathy – the onset of central AVS is usually abrupt. If spontaneous nystagmus increases with fixation suppression, this is more likely to indicate a peripheral cause. If head/neck pain is associated with recent trauma, consider vertebrobasilar dissection.

Episodic vertigo

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPLS) is the main representative of triggered episodic vestibular syndrome (t-EVS), whereas attacks of Meniere’s disease or vestibular migraine occur spontaneously (s-EVS). Far less common, but to be specifically looked for because of the potentially life-threatening consequences, are TIA, cardiac arrhythmias, and hypoglycemia. While TIAs usually have an abrupt onset and transient focal neurologic deficits, arrhythmias are usually associated with a cardiac history and/or cardiac symptoms (palpitations, presyncope).

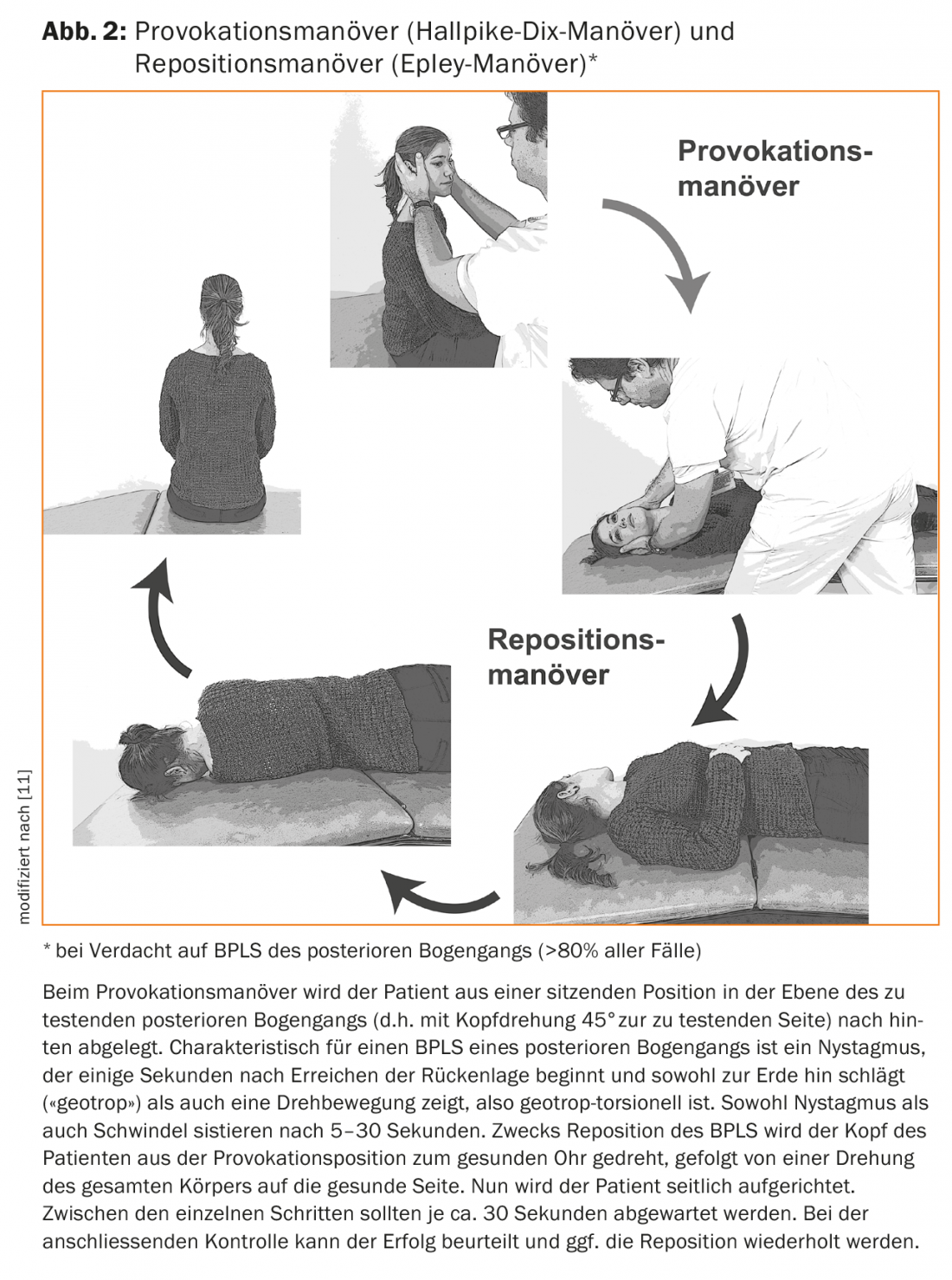

BPLS is a spinning vertigo of characteristic latency (5-10 seconds) after head position change (turning in bed, getting up/lying down, looking up/down) and short duration (5-20 seconds). BPLS commonly occurs after head impact or after damage to the vestibular nerve. By far the most common form (%–90%) involves the posterior arcades and results in torsional geotropic nystagmus in the Hallpike-Dix provocation maneuver. Treatment is by Epley repositioning maneuver (Fig. 2) . Diffuse fluctuating vertigo after a successful repositioning maneuver may persist for several days. Recurrence of first-time BPLS occurs in approximately 30% of cases. In refractory or atypical cases, a central cause (e.g., space-occupying lesions in the 4th ventricle) should be considered and an MRI should be performed.

Vestibular migraine corresponds to a special form of migraine and can be associated with headaches or occur in isolation. It is the second most common cause of episodic vertigo after BPLS. There must be a history of migraine headache [8]. The duration of vertigo attacks is highly variable (5 minutes to 72 hours). Supportive for the diagnosis of vestibular migraine is a therapeutic response to baseline migraine treatment.

Episodic vertigo or spinning vertigo lasting 20 minutes to 12 hours with accompanying ear symptoms (hearing loss, tinnitus, water/strange body sensation) are characteristic signs of Meniere’s disease. The visualization of endolymphatic hydrops in MRI is now possible. Nevertheless, differentiation from vestibular migraine is sometimes difficult or even impossible [9]. Thus, headache and photophobia may accompany attacks of Meniere’s disease, while ear symptoms may also be present in vestibular migraine.

Chronic dizziness

Chronic dizziness can be an expression of a persistent peripheral-vestibular deficit, but can also occur in the context of internal or psychiatric diseases. Gait disturbance due to peripheral polyneuropathy, visual impairment, or cerebellar degeneration may also be perceived as chronic vertigo. In these cases, however, the discomfort is present only when standing or walking, depending on the position.

In approximately 20% of peripheral-vestibular deficits that take place, the (usually central) compensation is insufficient and a unilateral loss of function results in persistent, load-dependent vertigo. More common, however, is vestibular insufficiency in the presence of bilateral failure. This clinical picture usually occurs insidiously. The most common causes include aminoglycoside-induced vestibulopathies and traumatic brain injury; in approximately 50% of cases, the cause remains unexplained. In these patients, there is a characteristic triad of bilateral pathologic head impulse test, marked stance unsteadiness with falling tendency at eye closure, and abnormal dynamic visual acuity (i.e., during head perturbations, visual acuity on the visual chart is reduced by >2 lines). Vestibular physical therapy has been very successful in these patients. An insidious onset of disease with gait unsteadiness, dizziness, and hearing loss is characteristic of the presence of vestibular schwannoma. An MRI examination brings clarity in these cases.

Conclusions

Due to the extremely broad differential diagnosis, a systematic approach with a structured history (focus on timing and trigger) and a targeted clinical examination is crucial in patients with leading symptoms of dizziness. Additional investigations should only be performed if the diagnosis cannot be made with sufficient certainty using clinical measures. Unnecessary or inappropriate diagnostics (such as a CT scan for suspected vertebrobasilar ischemia) should be avoided.

Literature:

- Newman-Toker DE, et al: Spectrum of dizziness visits to US emergency departments. Cross-sectional analysis from a nationally representative sample. Mayo Clin Proc 2008; 83: 765-775.

- Kroenke K, Jackson JL: Outcome in general medical patients presenting with common symptoms. A prospective study with a 2-week and a 3-month follow-up. Fam Pract 1998; 15: 398-403.

- Newman-Toker DE, et al: Imprecision in patient reports of dizziness symptom quality. A cross-sectional study conducted in an acute care setting. Mayo Clin Proc 2007; 82: 1329-1340.

- Büki B, et al: “Balance disorders in clinical practice. Verlagshaus der Ärzte, 2015.

- Tarnutzer AA, et al: Does my dizzy patient have a stroke? A systematic review of bedside diagnosis in acute vestibular syndrome. CMAJ 2011; 183: E571-592.

- Macdougall HG, et al: The video Head Impulse Test (vHIT) detects vertical semicircular canal dysfunction. PLoS One 2013; 8: e61488.

- Zwergal A, et al: A bucket of static vestibular function. Neurology 2009; 72: 1689-1692.

- Furman JM, et al: Vestibular migraine: clinical aspects and pathophysiology. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12: 706-715.

- Lopez-Escamez JA, et al: Accompanying symptoms overlap during attacks in Meniere’s Disease and Vestibular Migraine. Front Neurol 2014; 5: 265.

- Newman-Toker DE, Edlow JA: TiTrATE: A Novel, Evidence-Based Approach to Diagnosing Acute Dizziness and Vertigo. Neurol Clin 2015; 33: 577-599.

- Tarnutzer AA: Dizziness in the elderly. The Informed Physician 2015: 35-39.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2016; 14(2): 20-25.