Physicians are often asked by relatives and acquaintances for opinions, assessments and treatments. In doing so, however, they often enter an ethical gray area insidiously and unnoticed. The transition from professionally and personally acceptable treatment to an ethical dilemma is fluid. On the one hand, the existing guidelines and data should provide the basis for a discussion. On the other hand, examples will be used to highlight the dangers of entangling personal and professional relationships.

We doctors are often asked by relatives and acquaintances for opinions, assessments and treatments, especially because they know and trust us. However, in doing so, we often creep unnoticed into an ethical gray area. The transition from professionally and personally acceptable treatment to an ethical dilemma is fluid. On the one hand, we would like to provide the basis for a discussion here with the existing guidelines and data. On the other hand, examples will also be used to highlight the dangers of entangling personal and professional relationships.

Of course I can put a plaster on my own son’s cut. But should I stitch the wound on the knee myself; what if it’s on the chin? Should I stop antihypertensive therapy for my own father? Can I also talk to my father about side effects of antihypertensive therapy, especially erectile dysfunction? If the sister of a renowned heart surgeon needs heart surgery, who should perform it? May I renew my partner’s prescription for antidepressants?

What starts out as a simple medical problem suddenly turns out to be a problematic situation upon closer inspection. In such situations, we physicians find ourselves in a role conflict between the treating physician and the caring relative. The problem certainly comes to a head when the patient is a minor child or a parent with dementia.

The data situation

Data regarding the treatment of relatives by Swiss physicians do not yet exist. However, in 2002, a study was conducted on primary care physicians’ own medical care in Switzerland [1]. In this study, 2756 primary care physicians were randomly contacted from the FMH database to answer an online questionnaire. The response rate was 65% with 1784. This showed that only just 21% of Swiss GPs had their own GP, compared with 90% of the Swiss population as a whole. After all, 53% (940 physicians) of respondents reported receiving a medical consultation during the past year. 1152 physicians reported taking medications during the previous week, representing 65% of respondents. 90% of these did so with self-prescribed medications, which included analgesics, tranquilizers, antidepressants, and antihypertensives in descending order. The study concludes that Swiss physicians tend to self-medicate even for non-benign conditions.

A somewhat older but very informative study was published in 1991 [2]. In Chicago, all 691 physicians at one hospital were surveyed about treatment of relatives. Of the 465 responses received (response rate 65), 461 physicians, or 99%, indicated that they had been asked for a medical favor at least once by close family members. 57% of respondents “almost always” fulfilled such a request and an additional 38% “sometimes” did. These “medical favors” included “medications prescribed” (83%), “conditions requiring treatment diagnosed” (80%), “physical exams performed” (72%), to name just the 3 largest groups here. In 15%, colleagues reported acting as the primary physician in charge of a treatment in the hospital, 9% performed an elective surgery, and 4% performed an emergency surgery. It should be noted here that this survey included many non-surgeons and so the surgical numbers are not representative.

The Association of German Surgeons published a survey of its 16,849 members in 2017 [3]. 77.6% (1247) of the 1643 responding surgeons reported having performed surgery on family members or close friends at least once. Of these, however, nearly 40% (477) reported having had doubts before surgery.

The data of the 361 surgeons who have never operated on family members or close friends are also interesting. Of those, 59% said they had “never been in this situation before,” 13% complained that “it didn’t feel right,” 11% referred to “someone better,” and 17% said that the “doctor-patient relationship doesn’t work that way” or that “objectivity is lacking.” In 1% (2 cases), intervention was either by medical colleagues or by other relatives. In the operations performed, attempted intervention occurred in 96 cases (8.0%) by colleagues and in 12 cases (1.0%) by relatives or the patient himself. When asked if they would value “Ethical Support” or “Guidelines for Treating Relatives,” 30.8% answered “Yes.”

In summary, Swiss GPs are not afraid to self-medicate even for more complicated treatments. We may assume that they also do this for their next of kin, but Swiss data on this are still lacking. The data from both the U.S. and German surgeons powerfully demonstrate that family medical issues are a pervasive problem that affects all physicians.

Official Guidelines

There are only isolated guidelines on this topic [4]. This is certainly also due to the fact that the situations present themselves very differently. On the one hand, the nature of the private relationship between doctor and patient plays a role. On the other hand, the medical problems are very different. Certainly mental illnesses are very sensitive here, or when it comes to underage patients. The type of treatment that may be necessary also plays a role (surgical vs. medicinal), as does the associated potential for complications.

The most prominent guidelines are certainly the “Code of medical ethics opinion 1.2.1” of the American Medical Association (AMA) [5]. The latter generally advises against treating oneself or members of one’s family. As an exception, the code defines two situations:

- If no other physician is available due to an emergency situation or geographic isolation, relatives should also be treated. However, as soon as another doctor is available, the treatment should be handed over.

- When it comes to the brief treatment of a trivial matter.

In addition, framework conditions and limits are defined if relatives are nevertheless treated:

- Treatments should be documented and forwarded to the appropriate primary care provider.

- Physicians should recognize that treating loved ones can impact personal relationships.

- Sensitive and intimate treatments, especially of minor patients by family members, should be avoided.

- Family members will find it difficult to request treatment from an independent physician for fear of personally hurting the family physician.

Somewhat less detailed are the “Good medical practice” guidelines of the British General Medical Council (GMC) [6]. Here, it is simply pointed out that we physicians should avoid treating ourselves or people with close personal relationships.

The complexity of the subject matter means that these guidelines are written in a very rough and universal way. In addition, the American guidelines in particular allow a loophole with the undefined triviality. The fact that additional clear measures for the treatment of relatives have been defined shows that it is not assumed that they will be completely dispensed with. With this, the guidelines contradict themselves to a certain extent, but thus also adapt better to reality.

The complex extended doctor-patient relationship

The large discrepancy between the guidelines mentioned here and the reality depicted in the cited studies also shows the dilemma we face as physicians. This dilemma comes about in particular due to different roles and expectations and the associated conflicts. On the one hand, we take on the role of the treating physician, and on the other, that of the concerned relative. So, in the consultation room, we try to sit on both sides of the table at the same time.

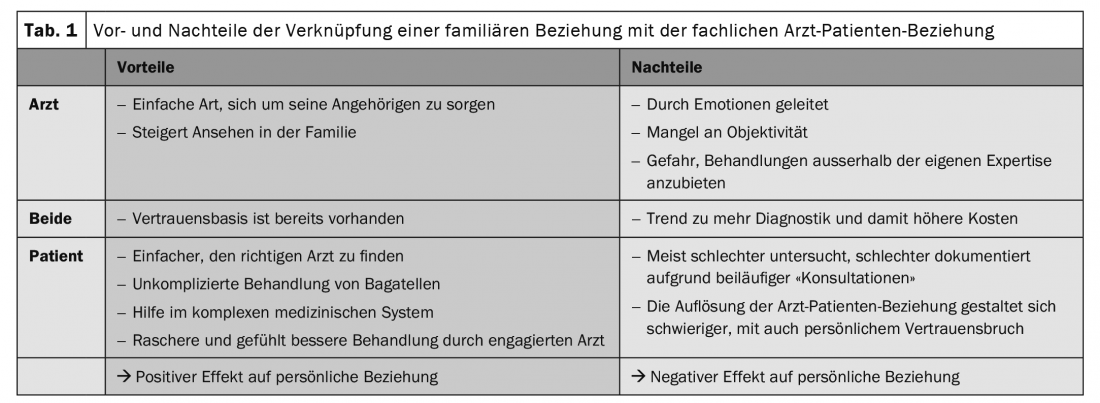

Generally, it is reassuring for patients to have a physician in the family. This can help navigate the complex medical system, explain medical terms and procedures, and provide reassurance that you will not fall victim to a gross medical error. Nevertheless, having a doctor in the family also poses dangers. Thus, the union of the private-personal with the professional doctor-patient relationship has advantages and disadvantages for both the patient and the doctor, which are summarized in Table 1.

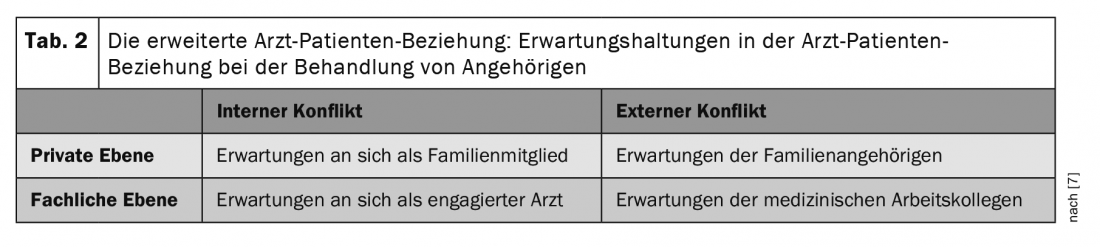

However, if one takes a closer look at the doctor-patient relationship, it becomes clear that it does not only consist of the two components “doctor” and “patient” and the associated interaction. The additional components of “relatives” and those of the physician’s medical “work colleagues” influence relationships in several ways. It is also important to note that the patient’s relatives are also part of the physician’s private-personal environment. We as relatives and also as physicians are thus confronted with different expectations (Table 2) [7].

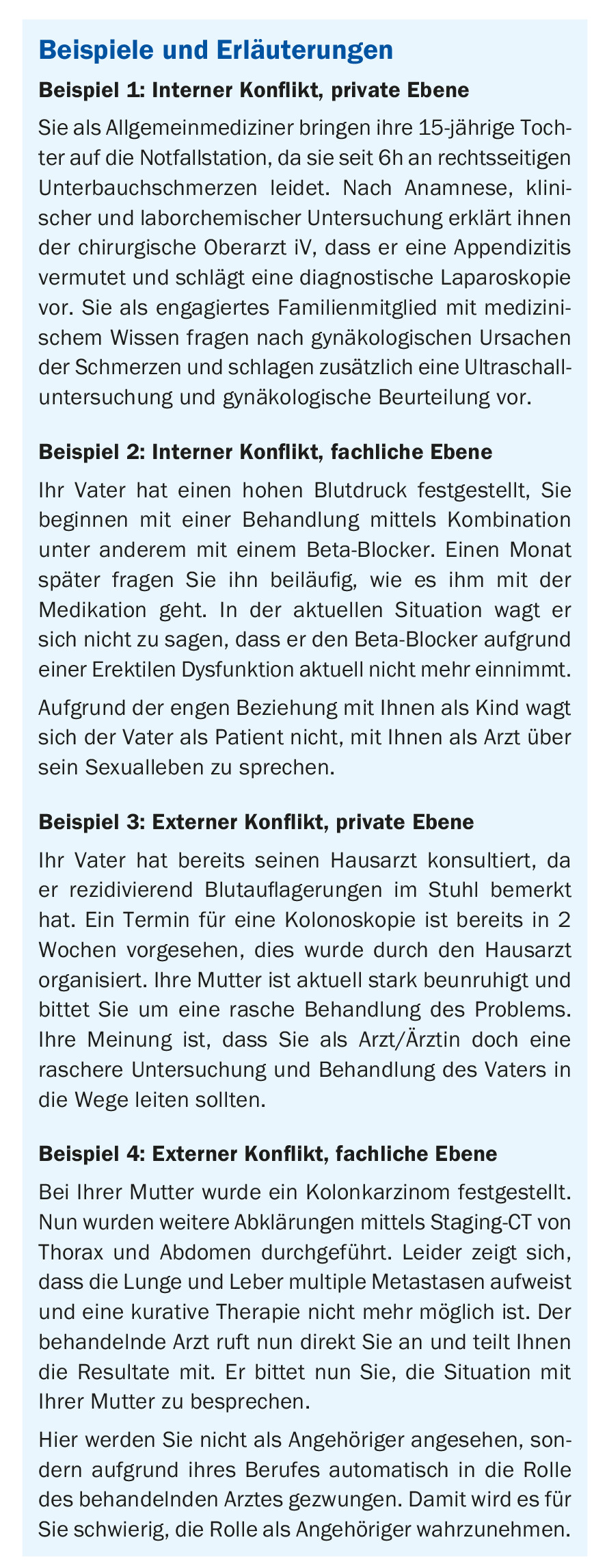

The physician is at the center and must explain himself both within the physician-patient relationship and outside, e.g., to family members, but also to medical colleagues. On the one hand, this conflict plays out “internally,” in terms of expectations of ourselves. On the one hand, we physicians want to fulfill our role as a caring “family member,” but in doing so, we cannot discard our role and knowledge as “medical professionals.” In turn, our expanded knowledge of the family situation, history, and treatment preferences helps to better assess the patient and direct them to the right therapy.

The “external” conflict consists on the one hand of the “expectations of the relatives”, who come to us in confidence with requests and medical problems. The relatives themselves usually expect strong involvement by us physicians in medical problems within the family. However, this commitment is expected not only from family members but also, in part, from physician colleagues who care for our next of kin (“expectation of other physicians”) .

Discussion

That there is a clear discrepancy between the guidelines presented and the common sense of physicians is also the conclusion of the work of Fromme et al. [8]. Involvement of physician relatives is taken for granted by most participants, especially for support and advice. Fromme et al. for this reason, replaced the strict rules of the guidelines with the self-reflection of the physician involved. To avoid the conflicts mentioned above, they advise us to consider solely, “What would I do if I had not obtained a medical degree?” In particular, they advise against explicitly medical actions. Another important point is also highlighted in this paper. If we persuade a loved one that a problem is nothing to worry about, it can have dangerous consequences. Such a statement from a health care professional should not prevent a proper consultation and examination.

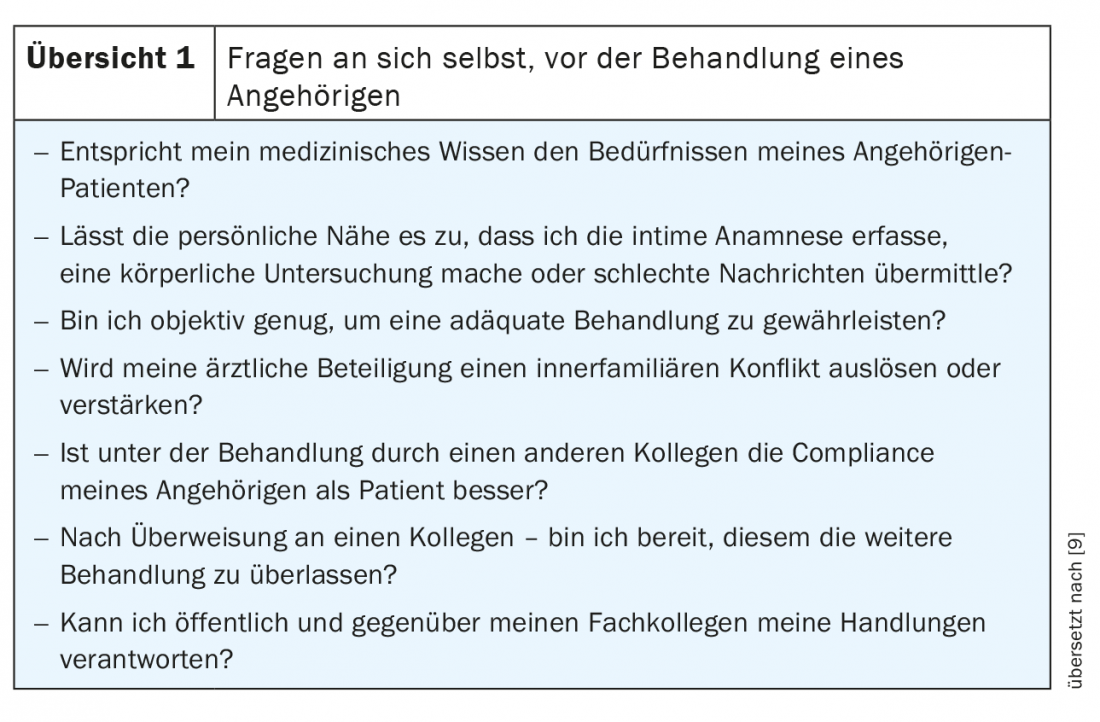

A similar approach to this problem was published back in 1992. La Puma et al. also relied on self-reflection, but here in more detail with 7 questions (Overview 1) [9]. Correctly answering the questions should guarantee the patient objective, fair and conflict-free treatment or just support in treatment.

Previously, only physicians were held accountable for questioning treatment of relatives. In this day and age of open communication and patient education, I believe that some of this responsibility can be passed on to the patient’s relatives. However, this requires that the trained clinician address the potential for conflict between the personal relationship and the professional relationship.

Summary

Since we medical professionals are also an important part of our family as a family member, and since the family in general enjoys a high status in society, it is impossible for us not to respond to medical requests from family members. The existing official guidelines clearly recommend not to get involved in the medical treatment of close relatives, but the few existing studies show that this is not lived in reality. Since this clear distancing from medical problems of relatives is not compatible with our social behavior, such an absolute rule is not enforceable.

When next of kin receive medical treatment, it is important that at least the physician is aware of the potential for conflict involved. Here, the physician must be aware of the various roles he or she assumes and the associated expectations of family members and physician colleagues. In order to set the boundaries of a doctor-patient relationship of relatives, it is useful to define them with critical self-reflection.

Take-Home Messages

- The treatment of relatives is a pervasive problem for us as physicians, which has great potential for ethical problems.

- Several guidelines are available, but there is a large discrepancy between guidelines and lived practice.

- Critical self-reflection should set limits to the treatment of relatives. In particular, ask yourself what options would be available to you even if you were not a physician.

Literature:

- Schneider M, Bouvier Gallacchi M, Goehring C, et al: Personal use of medical care and drugs among Swiss primary care physicians. Swiss Med Wkly 2007; 137(7-8): 121-126.

- La Puma J, Stocking CB, La Voie D, Darling CA: When physicians treat members of their own families. Practices in a community hospital. N Engl J Med 1991; 325(18): 1290-1294.

- Knuth J, Bulian DR, Ansorg J, Büchler P: When You Operate on Friends and Relatives: Results of a Survey among Surgeons. Med Princ Pract [Internet] 2017; 26(3): 235-244. Available from: www.karger.com/DOI/10.1159/000456617.

- Gold KJ, Goldman EB, Kamil LH, et al: No appointment necessary? Ethical challenges in treating friends and family. N Engl J Med 2014; 371(13): 1254-1258.

- American Medical Association. Code of Medical Ethics Opinion 1.2.1 [Internet]. [cited 2021 May 25]; Available from: www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/treating-self-or-family.

- General Medical Council. Good Medical Practice 2013; para 16.

- Chen FM, Feudtner C, Rhodes LA, Green LA.: Role conflicts of physicians and their family members: rules but no rulebook. West J Med [Internet] 2001 [cited 2019 Nov 17]; 175(4): 236-239; discussion 240. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11577049.

- Fromme EK, Farber NJ, Babbott SF, et al: What do you do when your loved one is ill? The line between physician and family member. Ann Intern Med 2008; 149(11): 825-831.

- La Puma J, Priest ER: Is there a doctor in the house? An analysis of the practice of physicians’ treating their own families. JAMA 1992; 267(13): 1810-1812.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(6): 4-7