More and more administration, economic pressure and political requirements that lead to conflicts of values with professional ethics – doctors have to be careful that their work does not become a burnout trap.

Are physicians more at risk than others for burnout?

Barbara Hochstrasser:

The thesis that doctors and people in other social professions are more likely to suffer from burnout than those in professions that do not primarily work with people was also raised by the first researchers on burnout (Maslach and Jackson), who originally formulated burnout as an “exhaustion syndrome of people who work with people”. However, they later found that members of other occupational groups also suffered from burnout and that it is not the occupational group but a number of other work-related factors that act as risk factors for burnout. A study of family physicians in Switzerland (Göhring) indicated that 3.5% suffered from severe burnout and 16-22% had significantly elevated scores in various burnout dimensions.

Leonid Eidelman, president of the World Medical Association, has warned of a “burnout pandemic among doctors” at the WMA’s general assembly in Reykjavik – exaggerated?

To warn against this is certainly correct, because the working conditions of physicians increasingly show more risk factors that promote burnout. Studies on physician burnout are increasing, especially in the U.S., and this may also be a reflection of increased attention to this phenomenon.

It’s not all the work that gets doctors down. Rather, they despair of bureaucracy, economic and political constraints. So is physician burnout a systemic disease?

You can certainly say that. Whereas a lot of work and long working hours are also risk factors for burnout. But it is indeed the enormous increase in administration, the economic pressure and the requirements imposed by politics that are very burdensome for physicians. This is because administration takes a lot of time, which then diminishes the time available for patients. The requirements often lead to conflicts of values among physicians and curtail physicians’ ability to do what is best for their patients according to their professional ethics. In addition, physicians must repeatedly justify the need for therapy to payers. At the same time, physicians are under high quality and expectation pressure from patients, payers and the public. In the public eye, physicians are not held in high esteem; rather, they are denounced as the main contributors to increased health care costs. The aforementioned study by Göhring found that family physicians with a heavy workload, high administrative activity, and uncertainty about changes in the health care system were particularly at risk for burnout.

Is a particular group of physicians particularly affected?

Several studies in different countries and medical specialties indicate that residents are particularly affected. In terms of personal risk factors, a lack of separation between work and private life is relevant, as are striving for perfection and a willingness to spend. In the Swiss GP study, men were more at risk, especially in the 45-55 age group and in rural areas.

First signs…?

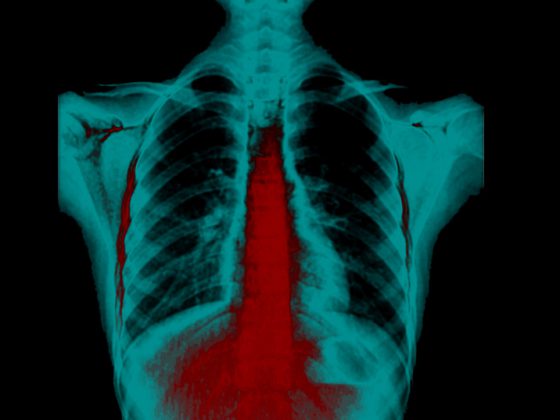

Burnout begins with prolonged exposure to stress. Nervousness, tension, difficulty concentrating and falling asleep as well as the feeling of not being able to switch off in the evening are typical signs. However, these symptoms cease when the stress load is over. The transition to burnout is often fluid, but in burnout the inability to switch off remains even when the stress load is over. A lack of ability to recover and the associated increase in fatigue are important early signs of burnout, as are forgetfulness and lack of concentration as well as susceptibility to infections and vegetative symptoms. However, there are also courses where the affected person feels very well for a long time and seems to function cheerfully at a high level of performance with little sleep. The high adrenaline release masks the increasing exhaustion. Suddenly, there is a breakdown, either with a hypertensive crisis and chest pain or the abrupt complete failure of all functioning, linked to an emotional breakdown. Afterwards, the affected persons are extremely exhausted, cognitively impaired and hardly able to cope with stress.

Differential diagnoses of burnout?

The differential diagnoses to burnout are numerous. Consideration must be given to internal diseases such as severe anemia or a metabolic syndrome, endocrine diseases such as hypothyroidism, diabetes, hypopituitarism, neurological diseases such as sleep apnea, MS, Parkinson’s disease, or myalgic encephalomyelitis (chronic fatigue), infectious diseases such as neuroborelliosis, malaria, or sleeping sickness, malignancies such as a craniopharyngeoma, and drug-induced fatigue. First and foremost, however, it is necessary to clarify the extent to which the person in question is suffering from depression or another psychiatric disorder, such as an anxiety disorder or addiction. These disorders are usually comorbid.

How did the Geneva Physician’s Vow come about, which calls for physicians to also take care of their own health in order to provide the best health care for patients?

The Geneva Physicians’ Vow is a contemporary version of the Hyppocratic Oath, which was originally adopted as an ethical guideline by the World Medical Association in 1948. Doctors around the world refer to it, and in some countries it is part of the professional code of conduct. It has been revised several times since then. In the latest 2017 revision, a new clause on maintaining one’s health and professional skills was included in light of the increasing workload and stress levels of physicians.

“I will take care of my own health, well-being and abilities to provide the highest level of care.” This formulation reflects that every physician also has a responsibility for his or her own health and that this health is a basic prerequisite for responsible medical practice. However, it also shows that the devotion to the medical profession also has a limit, because it must not lead to self-exploitation.

Burned-out physicians apparently struggle to provide optimal care to their patients, a study found. Could this also compromise patient safety?

Sick physicians pose a safety risk to patients when they experience cognitive decline or are emotionally unstable. Since burnout both causes cognitive dysfunction and leads to emotional lability, this is indeed a potential risk for patients.

What is effective prevention?

Burnout prevention means good self-care and a balanced lifestyle. Incorporating regular breaks into the working day, switching off in the evening, sleeping at least seven hours a night, physical exercise, if possible daily or at least three times a week, relaxation and meditation, cultivating your personal network of relationships and scheduling time for yourself – all this is crucial. And it is equally important to satisfy one’s personal vital needs and do what is meaningful and joyful for one.

What can you do if you, as an outsider, recognize the problem, but the person affected does not?

It is recommended to arrange a conversation in private and start it from the ME perspective: “I am worried because I have the impression that you are not doing so well”; “I observe that you look very tired, often seem absent and seem to forget things more often”; “Are you not feeling well?”; “Is there anything I can do to help you?” This can be an entry point to address the issue. Often, after all, a complete change cannot be made immediately. But at least awareness and/or slow change can be initiated.

What should colleagues avoid?

Blaming, accusing, or taking a mothering role or a physician-therapist position toward colleagues is not indicated. However, collegial friendly support and, if necessary, concrete assistance are useful.

One issue that concerns many physicians is the verbal and physical violence they increasingly encounter in their daily work – is this a burnout trigger?

Yes: Aggressiveness, devaluation or even violence are major social stress factors and have been shown to increase the risk of burnout.

What structural interventions in the workplace make sense – measures to shorten work shifts or a series of changes in clinical workflow? And what can be changed structurally in practice?

Today’s trend toward group practices and the possibility of part-time work offer great opportunities to curb the risk of burnout. This can reduce overall work time for individuals, share responsibility for emergency care and ongoing availability, simplify administrative processes, and reduce financial risk for individuals. Working hours should be interrupted by regular breaks and adequate rest periods should be observed. This applies both to the physician working in an institution and in a practice. In both places, stringent absence management, observance of regular vacations, prompt compensation for overtime and compliance with labor law requirements are very important. In addition, training supervisors in employee-oriented leadership and raising awareness of burnout are very effective interventions for everyone.

Re-entry after the crisis… or exit?

This is an individual decision. What is relevant is a very slow, gradual re-entry and a redesign of the way we work. It’s about reducing stress, building in breaks, avoiding excessive time pressure and maintaining good self-care. If this is successful at the old workplace, then re-entry is possible – provided that the work is fundamentally enjoyable and satisfying. If not, an exit or new start is indicated.

Is it possible to get out of burnout on one’s own or is outside help indispensable?

Making it on your own is very rare. It is advisable, especially to achieve a quick and lasting cure, to seek professional help.

The interview was conducted by Tanja Schliebe.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2019; 14(5): 44-46