The following article aims to provide an overview of the most common non-motor symptoms (NMS) in PD, their diagnosis finding and treatment, especially since some are treatable and their improvement has a significant impact on patients’ quality of life. Apathy may respond to dopaminergic therapy. In the case of depression, treatment should be primarily with dopaminergic therapy and then preferably with dopamine agonists with affinity for the D3- receptor. Therapy for psychosis and impulse control disorders initially involves reducing the responsible medication. Dementia can be positively influenced by therapy with cholinesterase inhibitors. Because dopamine plays a role in the sleep-wake cycle, sleep disorders may also respond to dopaminergic therapy. Optimization and the use of analgesics help with pain. Deep brain stimulation can also improve non-motor symptoms.

Non-motor symptoms (NMS) occur in the course of Parkinson’s disease in almost all patients [1]. It is a broad spectrum of symptoms that often limit quality of life more than motor symptoms and often do not receive sufficient attention from sufferers, caregivers, and physicians [2, 3]. As a result, they are also underdiagnosed and undertreated, with some of the symptoms being considered adverse effects of dopaminergic therapy.

In general, non-motor symptoms are clustered in advanced PD, but some such as hyposmia, REM sleep behavior disorder, or constipation and depression may precede motor PD by several years [4]. It is now well established that NMS such as depression or even sleep disturbances, but especially the total number of NMS, significantly reduce the quality of life in PD patients [3, 4]. The pathophysiology is complex and a distinction can be made between dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic symptoms; serotonergic and noradrenergic connections are also likely involved. According to the concept of ascending Lewy body pathology initiated by Braak and coworkers on the basis of autopsies [5], beginning in the olfactory bulb and inferior brainstem nuclei, some of the NMS seem to be explained as premotor symptoms (Fig. 1).

Histologic evidence of α-synuclein in sacral parasympathetic nuclei, sympathetic ganglia, and in the enteric nerve plexus also supports the hypothesis of ascending but also systemic pathology. The classic motor symptom triad can be assigned to stages three and four with involvement of the substantia nigra.

Table 1 provides an overview of the broad spectrum of NMS.

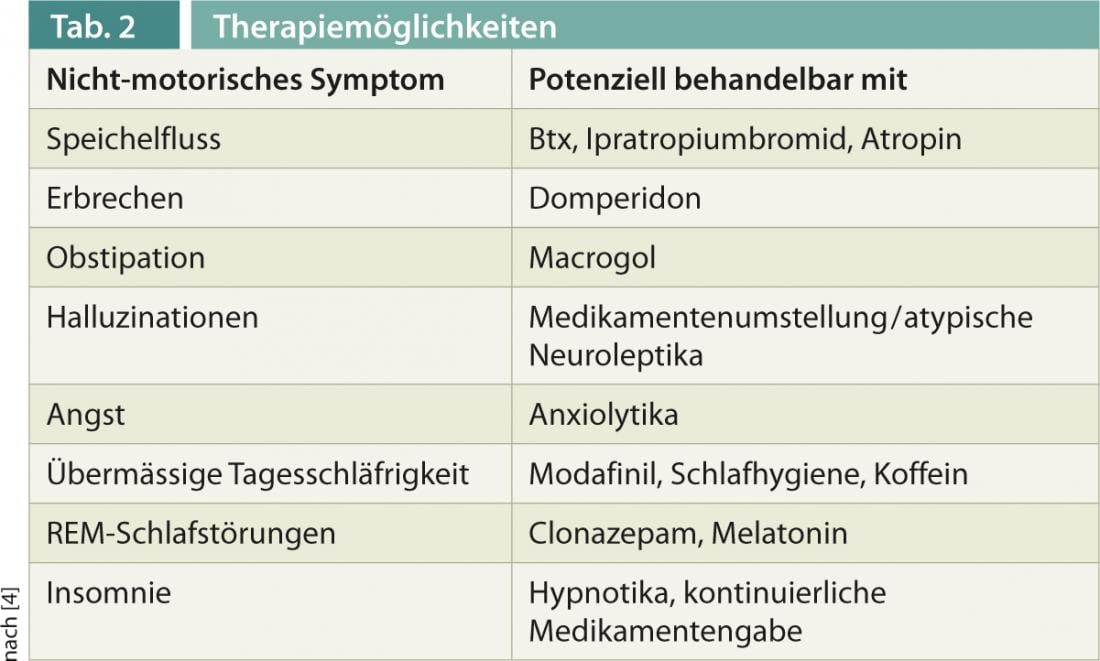

For the exploration and documentation of NMS, various scales have been established in recent years, such as the Non-Motor Symptoms Scale (NMSS), or questionnaires for targeted questions, such as the Parkinson’s Disease Sleep Scale (PDSS-2). Well-proven therapies now exist for some symptoms, which are presented below and also in Table 2 .

Apathy, depression and psychoses

Neuropsychiatric symptoms have a significant impact on quality of life, with nontremor-dominant PD patients at higher risk for cognitive decline, depression, apathy, and hallucinations [4].

Apathy is a specific problem in Parkinson’s disease and may respond to dopaminergic therapy, particularly the administration of dopamine agonists.

Depression may precede motor symptoms and there is no correlation between depression and the severity of motor Parkinson’s syndrome. Dopamine agonists with distinct affinity for the D3 receptor, here especially pramipexole and ropinirole, appear to be superior to other dopamine agonists in terms of their antidepressant effects. As a next step, the rather newer SSRIs and SNRIs can be used, and newer antidepressants such as mirtazapine, reboxetine, and venlafaxine are also considered here despite the still limited evidence [6].

Psychosis is one of the most disabling non-motor complications of Parkinson’s disease. Visual hallucinations may precede or accompany cognitive deterioration and are considered a warning signal for the development of dementia in PD [4]. Therapy, after ruling out other precipitating factors such as infections or metabolic disorders, consists first of reducing or discontinuing the responsible medications (in order: Anticholinergics, antidepressants, amantadine, dopamine agonists, MAO-B inhibitors, and most recently COMT inhibitors and levodopa) and then administration of atypical neuroleptics such as clozapine or also quetiapine, although only clozapine is approved for this indication.

Dementia, impulse control and sleep disorders.

The prevalence of dementia in PD patients is 30-40%. Age is considered the main risk factor for developing dementia, rather than disease duration. Initially, medications that may lead to cognitive deterioration should be discontinued, and in a second step, cholinesterase inhibitors are used, with the most convincing data for rivastigmine, which is approved for mild to moderate Parkinson’s dementia [4].

Impulse control disorders such as pathological gambling, eating, shopping, or even hypersexuality are usually not reported, also because of shame, and are more common in association with dopamine agonists as well as in men. Treating physicians need to actively ask about these symptoms because if impulse control disorders are overlooked, permanent severe relationship problems and also financial difficulties can result. Therapy consists of immediate reduction or discontinuation of dopamine agonists in particular.

Sleep disorders can present themselves in many ways (Tab. 1), are a very common and often serious problem, and can have various causes. Because dopamine plays a role in the sleep-wake cycle, some sleep disorders in PD may respond to optimized dopaminergic therapy. This has been shown, for example, for the transdermal rotigotine, which led to significant improvement in both morning motor impairment and sleep disturbance, recorded with the PDSS-2 [7]. When using dopamine agonists, attention must be paid to the possible side effects of increased daytime sleepiness and sudden attacks of falling asleep, which may necessitate dose reduction or even discontinuation [8]. REM sleep behavior disorder is characterized by acting out dreams (often nightmares) due to a lack of muscle atonia during REM sleep. Drug therapy consists of the use of clonazepam at night [9]. For the treatment of restless legs syndrome, dopamine agonists are mainly used, alternatively, depending on the severity, gabapentin or pregabalin, in severe cases also opioids [10]. An important component in the treatment of all sleep disorders always remains the maintenance of good sleep hygiene (regular sleep and wake time, adequate time in bed, i.e. usually no more than 8 hours). Other treatable causes of sleep disturbance, such as obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, should be excluded.

Pain

Pain is a common symptom in PD patients and can have many different causes (musculoskeletal, secondary to dystonia, central, radicular, neuropathic). Adjustment of dopaminergic therapy may lead to improvement, and in a next step the use of analgesics should be considered, depending on the cause.

In addition to motor fluctuations, deep brain stimulation (THS) in the nucleus subthalamicus improves the severity and fluctuations of non-motor symptoms such as paresthesias, pain, urinary urgency, dysautonomias, and sleep disturbances. Gastrointestinal symptoms are also alleviated, resulting in an overall noticeable improvement in quality of life one year after THS [11].

Relevance for neuroprotective therapies

Especially with regard to neuroprotective therapies that may be available in the future, early diagnosis taking into account the above-mentioned NMS could be of great clinical relevance [10]. The attention, research and therapy of NMS in PD will become increasingly relevant.

Stephan Nitschke, MD

Prof. Dr. med. Barbara Tettenborn

Stefan Hägele-Link, MD

Literature:

- Barone P, et al: The PRIAMO study: a multicentre assessment of nonmotor symptoms and their impact on quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2009; 24(11): 1641-1649.

- Chaudhuri KR, et al: The nondeclaration of nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease to health care professionals: an international study using the nonmotor symptoms questionnaire. Mov Disord 2010; 25 (6): 704-709.

- Chaudhuri KR, et al: Parkinson’s disease: The non-motor issues. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2011 Dec; 17(10): 717-723.

- Chaudhuri KR, et al: Handbook of Non-Motor Symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Springer 2011.

- Braak H, et al: Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 2003; 24 (2): 197-211.

- DGN Guidelines, September 2012.

- Trenkwalder C, et al: Rotigotine effects on early morning motor function and sleep in Parkinson’s disease: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study (RECOVER). Mov Disord 2011, 26(1): 90-99.

- Maass A, et al: Sleep and non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm 2013 Apr; 120(4): 565-569.

- Aurora RN, et al: Best practice guide for the treatment of REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD). J Clin Sleep Med 2010; 6(1): 85-95.

- Garcia-Borreguero D, et al: European guidelines on management of restless legs syndrome: report of a joint task force by the European Federation of Neurological Societies, the European Neurological Society and the European Sleep Research Society. Eur J Neurol 2012; 19(11): 1385-1396.

- Steigerwald F, Volkmann J: Deep brain stimulation (THS) in Parkinson’s disease: assess indication for THS already at first effect fluctuations. InFoNeurology&Psychiatry 2013; 15(5): 38-45.