Assessing the suitability for travel is complex. In addition to any existing underlying disease, risks at the travel destination and the personal attitude of the traveler play a role. In case of pregnancy, the need for travel should be critically questioned.

Swiss residents took 5.8 million air trips abroad in 2015, with an upward trend despite crises and terrorism [1]. In the same year, over 1000 people were repatriated due to accidents and illness, and some died abroad. In the following, I would like to discuss, from the practitioner’s point of view, the preparation of the trip in case of pre-existing medical problems and pregnancy. In addition, important travel and vaccine-related issues facing primary care providers will be discussed.

Flight and travel suitability

Increasingly, travelers include people with pre-existing medical conditions. For this reason, family physicians are also confronted with the question of fitness to fly.

There is a reduced oxygen partial pressure in the flight cabin corresponding to an altitude of approximately 2000 m. Passengers must be able to remain in a seated position for extended periods of time with limited ability to move regularly. A medical emergency on board may result in a layover, travel delays and huge costs.

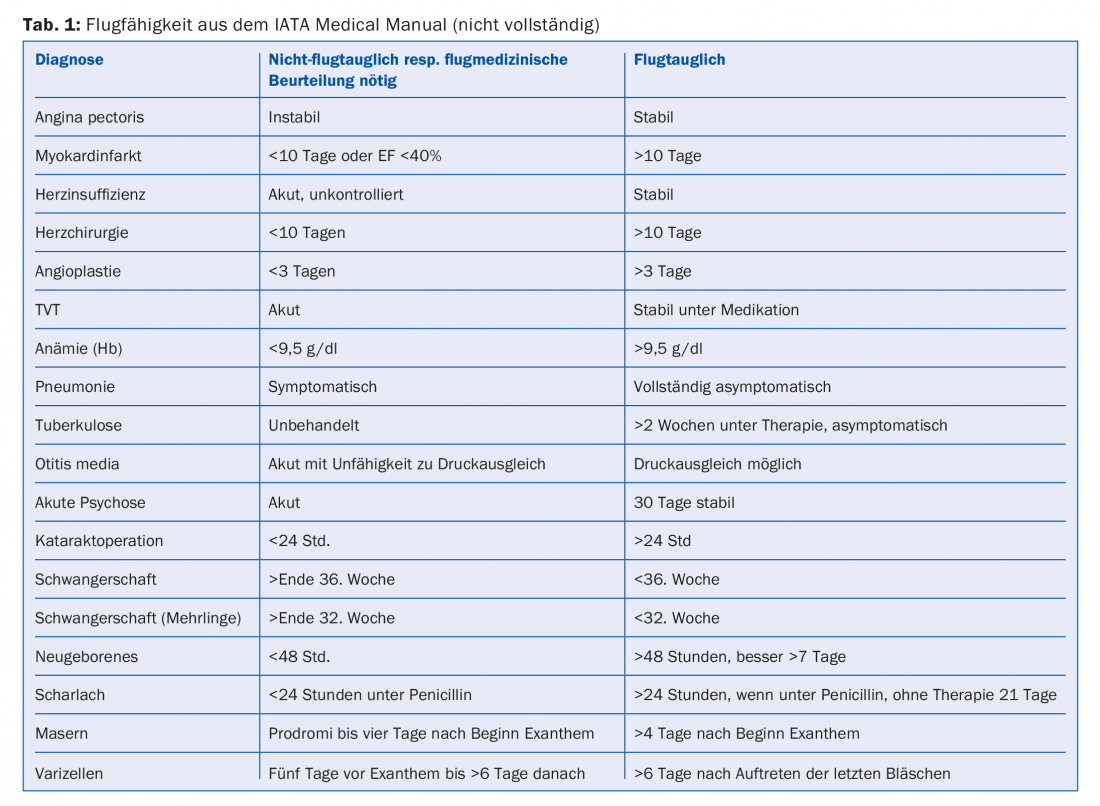

Airworthiness is clearly defined: The IATA (International Air Transport Association) Medical Manual [2] describes in detail the criteria that must be met for fitness to fly (Tab. 1) . All patients who do not meet these criteria must be assessed by an aviation physician. The guidelines are based primarily on practical experience rather than scientific research.

Beyond mere “airworthiness,” several additional factors play a role in the broader “fitness to travel.” Among other things, the conditions at the destination such as hygienic conditions, medical care, rescue possibilities in remote areas, climatic conditions and altitude or endemic infectious diseases on site (e.g. malaria, traveler’s diarrhea). Essential, however, is the personal attitude of the traveler. An elderly gentleman who has set himself the life goal of “seeing Mt. Everest one day” will take higher risks than his neighbor who still wants to “enjoy his grandchildren for as long as possible”. Our role is to educate about potential health risks, discuss solution algorithms for emergencies, and provide individualized decision making for the patient.

Divers should not fly 24 hours after their last dive.

Travel during pregnancy

Here is a brief case study: A couple comes for travel advice, they are planning a honeymoon in Botswana and Zimbabwe with departure in four weeks. There, a significant increase in malaria cases has just occurred due to numerous rainfalls. The woman recently knows she is pregnant and asks if she can fly.

Comment: Up to the end of the 36th week of pregnancy (32nd SSW in the case of multiple pregnancy), flying is permitted in the case of uncomplicated pregnancy. From the 28th week, SWISS recommends carrying a certificate confirming that the pregnancy is uncomplicated and that the woman is fit to fly. The certificate should state the expected date of delivery.

In the case study described above, travel should be discouraged in order not to expose the woman and the unborn child unnecessarily to a health risk, e.g., from malaria. The couple was then eventually grateful for this advice and rebooked their trip to a less problematic destination.

We have another situation, for example, with a pregnant woman who works for an aid organization in Africa and is married to an African. Here, the various risks and possibilities for prevention (exposure prophylaxis, mosquito protection and medicinal prophylaxis) have been discussed in detail. The woman decided to make the trip after careful consideration. Their main argument was “my life is in Africa and not here”. However, such situations are rare and should clearly remain the exception.

Travel with risks for thrombosis

There are no uniform recommendations regarding thromboprophylaxis during air travel [3]. Air travel over four hours increases the risk of thrombosis by a factor of 2. Additional risk factors such as history of unprovoked DVT (deep vein thrombosis), familial predisposition to DVT, pathologic coagulation tendency, pregnancy, hormone replacement medications, age >40 years, obesity, recent trauma, or recent surgery further increase the risk.

According to the recommendation published in SMF in 2015 [4], compression stockings should be worn when traveling for more than four hours and when additional risk factors are present (as in the above example with the pregnant woman). If multiple risk factors accumulate, additional anticoagulation with medication may be considered. In practice, it has been shown that sensitized patients tend to want anticoagulation even when the risk is objectively low. It should be emphasized that no preparation for thromboprophylaxis is registered for this purpose, the prescription is “off label”. We need to inform our patients about this.

The oral anticoagulants (e.g., rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and apixaban) greatly facilitate their use. However, dose adjustments for weight and renal insufficiency must be considered. Interactions exist with numerous drugs (CYP34A, CYP2J2, and CYP-independent mechanisms: e.g., azoles, clarithromycin, HIV protease inhibitors, rifampicin, various antiepileptic drugs). The low-molecular-weight heparins (e.g., dalteparin, enoxaparin), which were most commonly used in the past, are simpler with regard to interactions.

Travel with other diseases

The procedure for all pre-existing conditions should always be discussed with the attending physician (general practitioner or specialist, e.g. cardiologist or diabetologist). Drug therapies are numerous and always changing. Thus, the prescribing physician is usually in the best position to make recommendations (e.g., how to proceed if there is a time difference). In principle, the handling of drugs with a long half-life is easier. In most cases, it can continue to be taken at the usual time. With a shorter HWZ, it may be necessary to gradually change the time of administration in the event of major time differences.

A confirmation issued by a physician should be available for medications carried, especially for syringes and needles, polymedication or a large number of tablets.

It should also be noted that a sufficient amount of medication is carried in the hand luggage in case of loss of the checked luggage. I recommend to carry an additional reserve in the checked baggage, because the hand luggage can also get lost once.

For diabetics, helpful documents for travelers and their physicians exist and can be downloaded from the website of the Swiss Diabetes Society [5].

When traveling under opioid substitution, the prescribed procedure must be followed and the appropriate form must be given to the patient [6].

Frequently asked questions regarding vaccinations and malaria prophylaxis

Country-specific travel medicine information can be found on “safetravel” [7] or in the more detailed fee-based “tropimed” [8].

We continue to receive questions about vaccinations from other primary care physicians. I would like to mention the most common ones here in conclusion:

- Yellow fever only exists in Africa and South America. There is no yellow fever in Asia and no vaccination is required. The following wording in “safetravel” often causes confusion, e.g. Thailand: Vaccination obligatory (not for airport transit passengers) for entry within ten days from yellow fever endemic area (not for airport transit there).

- Titre checks are practically never indicated (exception: hepatitis B vaccination in cases of high risk of infection, e.g. in medical personnel). In case of uncertainty, e.g. whether a second hepatitis A vaccination has been performed, vaccination should be performed again without titer control.

- A complete vaccination against hepatitis A and/or B will most likely result in lifelong protection. Booster vaccinations do not need to be given every 10-30 years [9].

- Every vaccination counts, i.e. even after long intervals between vaccinations, it is not necessary to start “all over again”.

Take-Home Messages

- Airworthiness is relatively clearly defined. Many more factors are involved in assessing fitness to travel (underlying disease, risks at the destination such as health care, endemic infectious diseases, e.g., malaria, heat or altitude, and the personal attitude of the traveler).

- In case of pregnancy, it should be questioned very critically whether the trip really has to be.

- For prophylaxis of deep vein thrombosis during air travel, it is recommended to wear compression stockings when traveling for more than four hours and additional risk factors are present. In certain situations, the use of low-molecular-weight heparins or oral direct thrombin inhibitors may be considered.

- Travel with pre-existing medical conditions is best discussed with the attending physician, if necessary in cooperation with a physician experienced in travel medicine.

Literature:

- Swiss Federal Statistical Office: Travel Behavior. www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/tourismus/reiseverhalten. assetdetail.1585223.html

- IATA: Medical Manual. 2017, 9th edition, February.

- Aerospace Medical Association: Medical guidelines for airline travel. Aviation, Space and Environmental Medicine 2003; 74(5): Section II.

- Von Wattenwyl, et al: Travel time is flight time. Thrombosis risk, jet lag, and cardiac surgery. Swiss Medical Forum 2015; 15(39): 860-865.

- Diabetes Switzerland: Brochures. www.diabetesschweiz.ch/diabetes/uebersicht-broschueren/reisetipps/

- Swissmedic: Schengen Agreement – Travel with medicines containing narcotics. www.swissmedic.ch/bewilligungen/00155/00242/00243/0042 /00429/index.html?lang=en

- Safetravel. www.safetravel.ch

- Tropimed. www.tropimed.ch

- BAG: Vaccinations for travel abroad. 2007 January.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(6): 12-14