“Try to relax and breathe calmly. Very calmly. If you now find breathing uncomfortable, you have already experienced the problem of dyspnea” – in this or a similar way, the general practitioner makes it clear to the patient what dyspnea is all about. Dyspnea (shortness of breath) is defined as “subjectively unpleasant perception of breathing composed of qualitatively circumscribed sensations of varying intensity,” according to the 1999 ATS Consensus Statement. The following article provides an overview of this clinical picture.

Dyspnea is determined solely by the individual who has it and is therefore not easily quantifiable. For semiquantitative assessment of dyspnea, the Medical Research Council (MRC) Breathlessness Scale [1] or the similarly structured New York Heart Association (NYHA) scale have proven useful.

Respiratory distress serves as a warning and protective mechanism of the respiratory system against harmful aberrations such as hypercapnia, hypoxia, and respiratory pump overload [2]. Respiratory distress can be explained pathophysiologically by a dysbalance of proprioceptors in the chest wall, respiratory muscles and airways, nociceptive receptors in the lungs and airways, and chemoreceptors forCO2 and O2 and is processed in the anterior insula and amygdala [3,4].

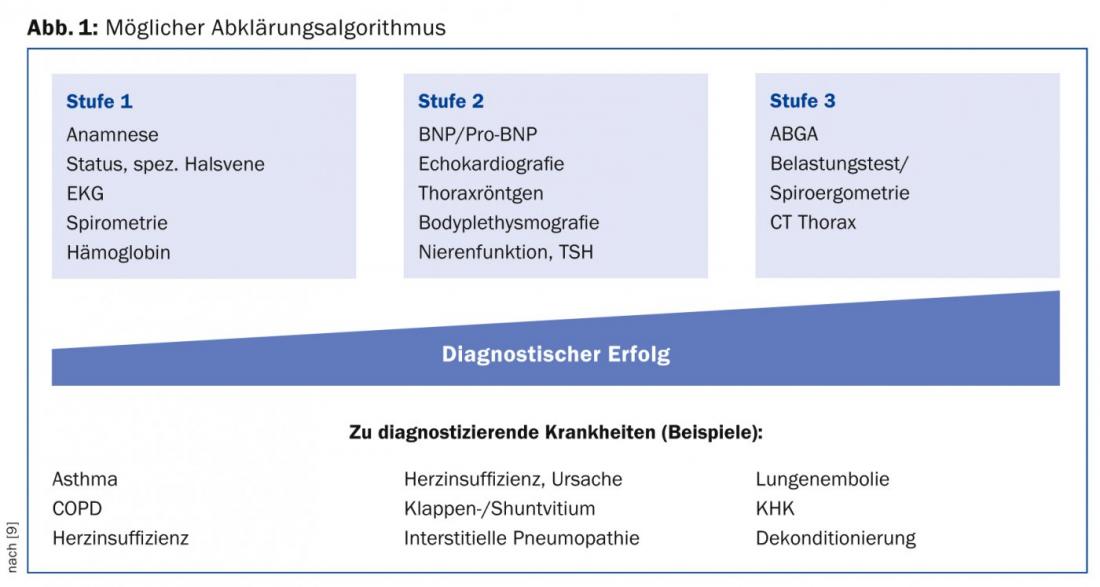

Do not confuse dyspnea with tachypnea, hyperpnea, hyperventilation, or painful breathing. Also, dyspnea is far from always associated with changes in blood gases. For example, patients with emphysema and hypercapnia on oxygen do not necessarily have dyspnea (“CO2 narcosis“). Although dyspnea is a common phenomenon (it is believed that about 30% of people over sixty years of age experience dyspnea during everyday tasks), there are no universal and reliable algorithms to help clarify it. A step-by-step approach is generally recommended, as shown in Figure 1 .

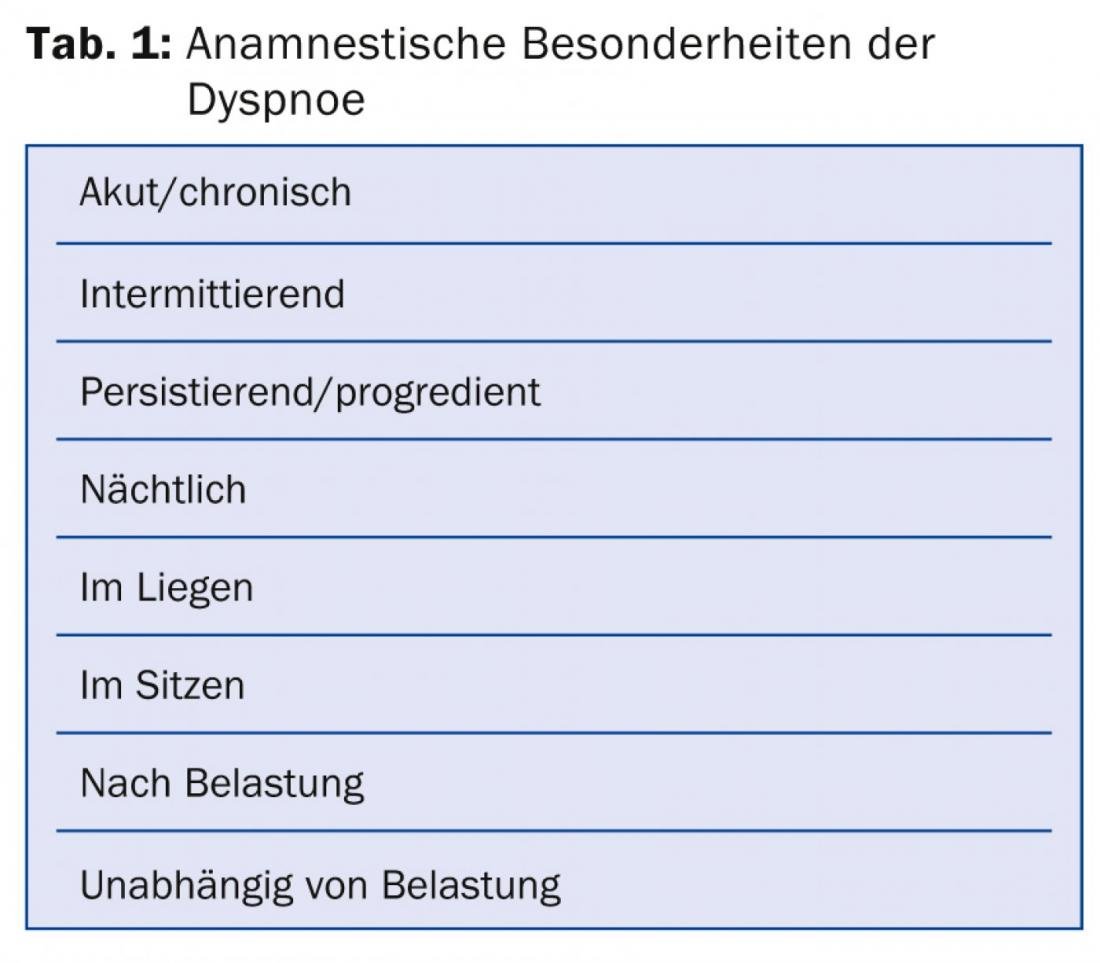

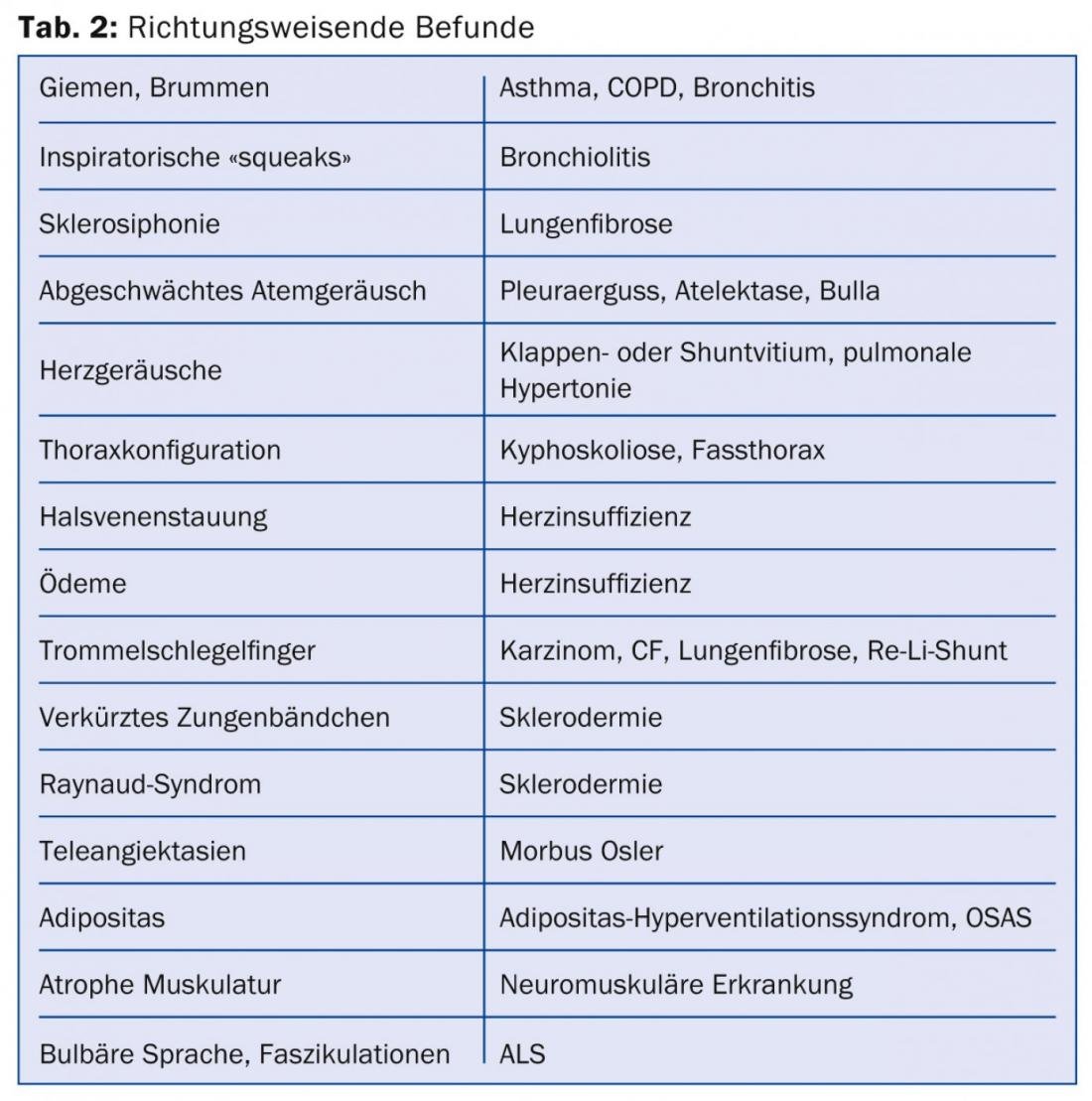

The most important clarification steps can be performed in the general practitioner’s office and do not require expensive equipment. The history and status reveal the cause of dyspnea in most cases, and both must be done conscientiously and without time pressure. Thus, anamnestic features and additional symptoms should be asked for, as listed in Table 1, and specific signs should be sought, as shown in Table 2.

What are the causes?

For both acute and chronic dyspnea, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases are by far the most common causes. A third important category is functional or psychogenic causes, whereas anemia, acidosis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, or myasthenia cause dyspnea much less frequently.

In the following, some peculiarities of diseases that make dyspnea will be explained.

Asthma: asthma is a common disease and not always easy to diagnose because bronchial obstruction is by definition intermittent. Interestingly, the symptoms of asthmatics correlate poorly with their respective lung function, making the disease insidious. Asthmatics with little dyspnea are particularly at risk because their bronchial obstruction is underestimated and patients are at risk of being undertreated [5]. Asthma control is said to occur when symptoms occur no more than twice a week, no nocturnal symptoms are present, on-demand medication is needed no more than twice a week, and lung function is normal [6].

“Vocal cord dysfunction”: a functional respiratory disorder and important differential diagnosis to bronchial asthma is “vocal cord dysfunction”, an intermittent, usually inspiratory airway obstruction caused by paradoxical vocal cord adduction, causing acute respiratory distress [7]. Young women are frequently affected. Possible triggers are thought to be reflux, “postnasal drip” or a mental disorder. Breathing therapy, relaxation or possibly psychotherapy can help.

“Hyperventilation syndrome”: “Hyperventilation syndrome” is not a diagnosis in its own right, but an accompanying symptom of organic disorders or panic attacks. Accordingly, the underlying problem must be treated, not hyperventilation per se.

Respiratory rate measured per minute belongs in every status of a patient with dyspnea. Not only is it a criterion for the diagnosis of sepsis, it is also prognostic in patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CRB-65 score).

COPD: It is clear that very common chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) must be diagnosed by history and status, and pulmonary function testing must be used for diagnosis and staging. It is therefore all the more astonishing that, according to a study from the Münsterlingen Cantonal Hospital (2005), 29% of patients hospitalized with exacerbated COPD had not had a pulmonary function test performed by that time [8]. Spirometers are small and inexpensive these days and belong in every family doctor’s office.

Cardiac dyspnea: Cardiac dyspnea is synonymous with heart failure. According to the European Heart Society ESC, heart failure is defined as a clinical syndrome with typical symptoms of heart failure (to be ascertained by history, usually dyspnea), typical signs of heart failure (to be experienced by means of status), and objectifiable structural or functional pathology of the heart at rest (including ECG changes, BNP elevation, cardiomegaly, etc.). Examination of the jugular vein (V. jugularis externa) requires special attention, especially in chronic heart failure, because it allows not only a qualitative assessment of central venous pressure but also an excellent evaluation of the success of therapy. However, the character must be searched for precisely. The jugular vein is assessed in the supine position at 0 and at 45°. 45° is the bisector of the right angle and it is steeper than commonly thought. For an accurate examination, a suitable couch is required with which the head section can be raised sufficiently. Once heart failure has been diagnosed, additional tests are needed to find its cause. In addition to the ECG (chronic infarction?), echocardiography is particularly suitable for this purpose.

Chronotropic insufficiency: One should not forget chronotropic insufficiency as a cause of dysnpoea and special form of heart failure. It is easy to find by means of a stress test. If a bicycle ergometer or a walking ergometer is not available or cannot be operated by the patient, a walk test on the flat (e.g. the standardized 6-minute walk test) or a non-standardized stress test on the stairs, which can be performed easily and almost everywhere, is suitable. Patients with pacing may also have chronotropic incompetence that is easily remedied. By switching on and optimizing the sensor (also called “rate response”), usually an accelerometer, the pulse rise under stress can be improved. The activity of the sensor is indicated by the fourth letter of the pacemaker code: e.g. VVIR and DDDR as opposed to VVI and DDD.

Ticagrelor therapy: a rare cause of dyspnea may be therapy with the antiplatelet agent ticagrelor. Brilique® causes dyspnea about twice as often as clopidogrel, i.e., in about 14% of cases. Fortunately, dyspnea is rarely severe and prognostically favorable.

Johann Debrunner, MD

Literature:

- Bestall JC et al: Thorax 1999; 54: 581-586.

- Brack T: Praxis 2009; 98: 703-709.

- Manning HL, et al: N Engl J Med 1995; 333: 1547-1552.

- Von Leupoldt A, et al: AJRCCM 2008; 177: 1026-1032.

- Teeter JG: Chest 1998; 113: 272-277.

- GINA Report, Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention 2014.

- Newman KB, et al: Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995; 152: 1386-1386.

- Fritsch K, et al: Swiss Med Wkly 2005; 135 (7-8): 116-121.

- Pedersen F, et al: Int J Clin Pract 2007; 61(9): 1481-1491.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- The vast majority of causes of dyspnea are resolved in the primary care physician’s office.

- Dyspnea is not the same as a blood gas disorder.

- Spirometry is simple, inexpensive, and recommended for every family practice.

- A suitable couch is indispensable for the evaluation of the jugular vein.

- Rare doesn’t mean never – think ticagrelor and “vocal cord dysfunction” as a cause of dyspnea.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(8): 14-16