Progressive diabetes mellitus type 2 is characterized by a continuous decrease in endogenous insulin secretion. Insulin remains a proven and very effective antidiabetic drug. The choice of insulin therapy is based on various factors such as diabetes stage, metabolic control, and patient resources. Initially, the vast majority of type 2 diabetics can be treated with basal insulin therapy. It has the lowest risk of hypoglycemia and weight gain compared to other insulin regimens (prandial insulin therapy, mixed insulin therapy). In clinical practice, the combination of insulin and GLP 1 analogues is becoming increasingly popular.

Pathogenetically, type 2 diabetes mellitus is characterized by insulin resistance and progressive restriction of insulin secretion. As a result, high fasting blood glucose levels and postprandial blood glucose spikes are typically found. Therefore, to maintain adequate metabolic control, most patients require insulin therapy during the course of the disease. Insulin therapy is still often started or considered too late. The reasons for this are varied and include fear of side effects (weight gain, hypoglycemia) and numerous other factors (e.g., inhibition from self-injection, fear of compromising quality of life, etc.) [1,2].

From a purely therapeutic point of view, insulin offers numerous advantages: Insulin is the antidiabetic drug with the greatest therapeutic efficacy and is easily controllable, has no relevant interaction potential with other drugs, is not contraindicated even in severe cardiac, renal, or hepatic insufficiency, and additionally has a positive effect on plasma lipids [3]. Side effects such as hypoglycemia and weight gain can often be well controlled or largely prevented with appropriate training and dose adjustment or choice of appropriate therapeutic regimen (e.g., combination with GLP 1 receptor agonists). Modern insulin therapy therefore remains a very efficient and modern therapeutic option in the multimodal treatment concept for type 2 diabetics.

The purpose of this article is to provide an up-to-date and practical overview of insulin therapy in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

HbA1c target values and therapy algorithms

The determination of the HbA1c target range is individualized for each patient. Various factors are taken into account, such as age or life expectancy, comorbidities, and risk of hypoglycemia [4]. The importance of good metabolic control with regard to the development and progression of microvascular sequelae such as diabetic retinopathy or nephropathy is undisputed. In contrast, the impact of good glycemic control on macrovascular complications has not been conclusively established. Although some benefit of early and good glycemic control on cardiovascular outcome after years was shown in the UKPDS trial [5]. However, in subsequent studies (ADVANCE, ACCORD, VADT) conducted primarily in patients with long-standing diabetes, intensive glycemic control aiming at HbA1c levels below 7% did not reduce cardiovascular mortality [6–8]. In general, most professional societies specify HbA1c around or below 7%, but with the option of higher (e.g., older patients with comorbidities) or lower (e.g., younger patients with short duration of diabetes and low risk of hypoglycemia) HbA1c targets.

In the current ADA/EASD recommendations for the treatment of hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes, treatment with basic insulin is found to be a therapeutic option with the greatest therapeutic potency on par with oral antidiabetic agents. Since insulin therapy has potential side effects, but also entails effort in terms of training and medication application, it makes sense in practice to weigh the indication for insulin therapy against the other antidiabetic therapy options, taking into account potency and side effects.

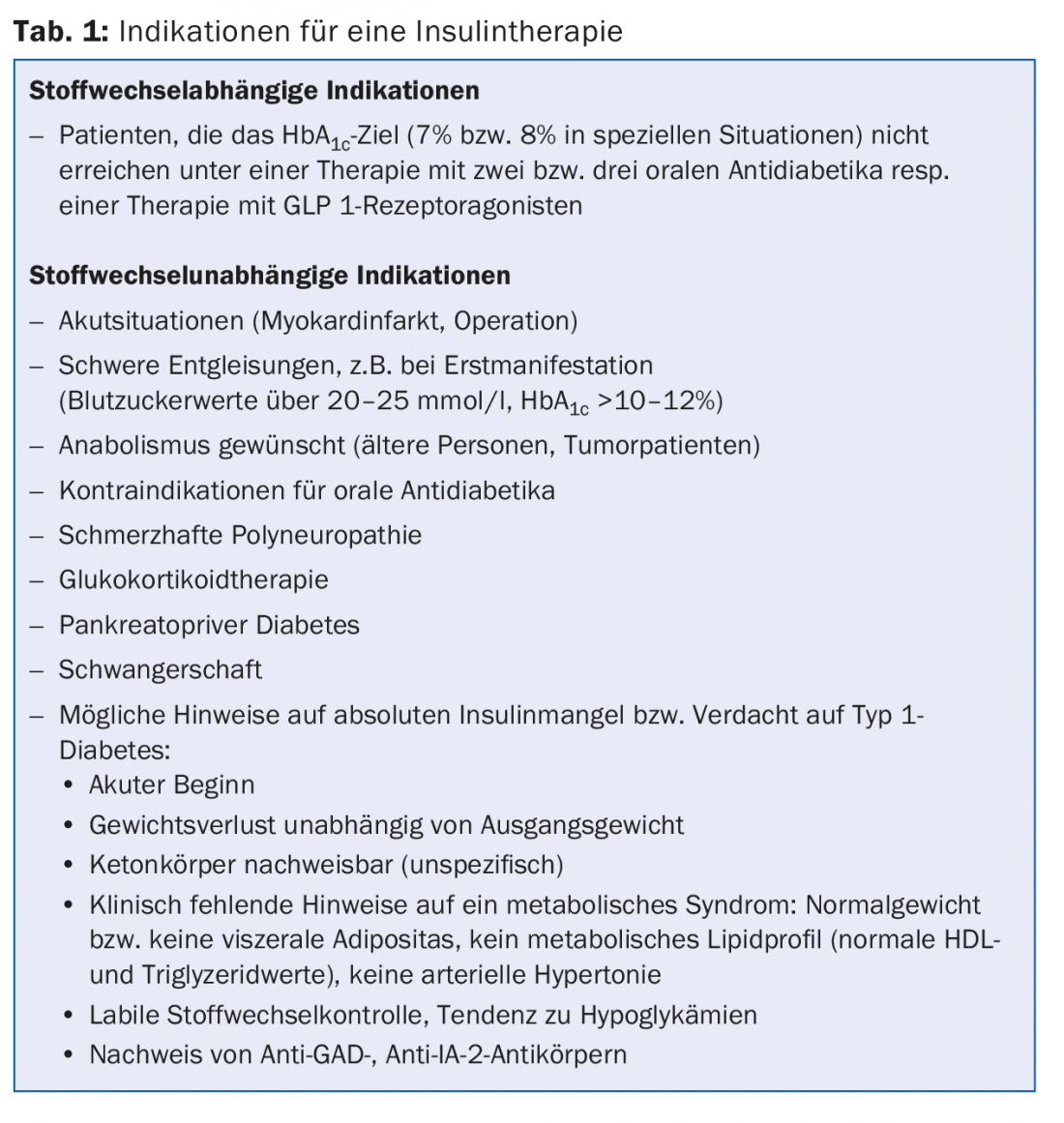

Indications for insulin therapy

In addition to metabolic indications (deterioration of metabolic control under dual or triple combination with oral antidiabetics with increase in HbA1cvalue), there are a number of metabolism-independent situations in which insulin therapy makes sense (Table 1). Often, in the acute situation with pronounced hyperglycemia (“glucotoxicity”), apart from the corresponding symptoms with polyuria and polydipsia, there is a kind of “secretory rigidity” of insulin secretion and a decrease in insulin action. Here, insulin therapy – which is often only needed temporarily – helps to lower blood glucose quickly and efficiently so that beta cell function and insulin resistance improve again. In addition, it has been shown that in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus, early intensified insulin therapy (compared with oral antidiabetic drugs) leads to significantly better recovery of beta-cell function and longer glycemic remission [9]. In a substantial proportion of patients, type 1 diabetes mellitus does not manifest until after 35 years of age [10], and up to 14% of all patients who phenotypically impersonate type 2 diabetics have detectable islet cell autoantibodies as an expression of autoimmune pathogenesis of diabetes [11]. If there are indications of an absolute insulin deficiency or type 1 diabetes mellitus, the initiation of insulin therapy is also indicated in this situation.

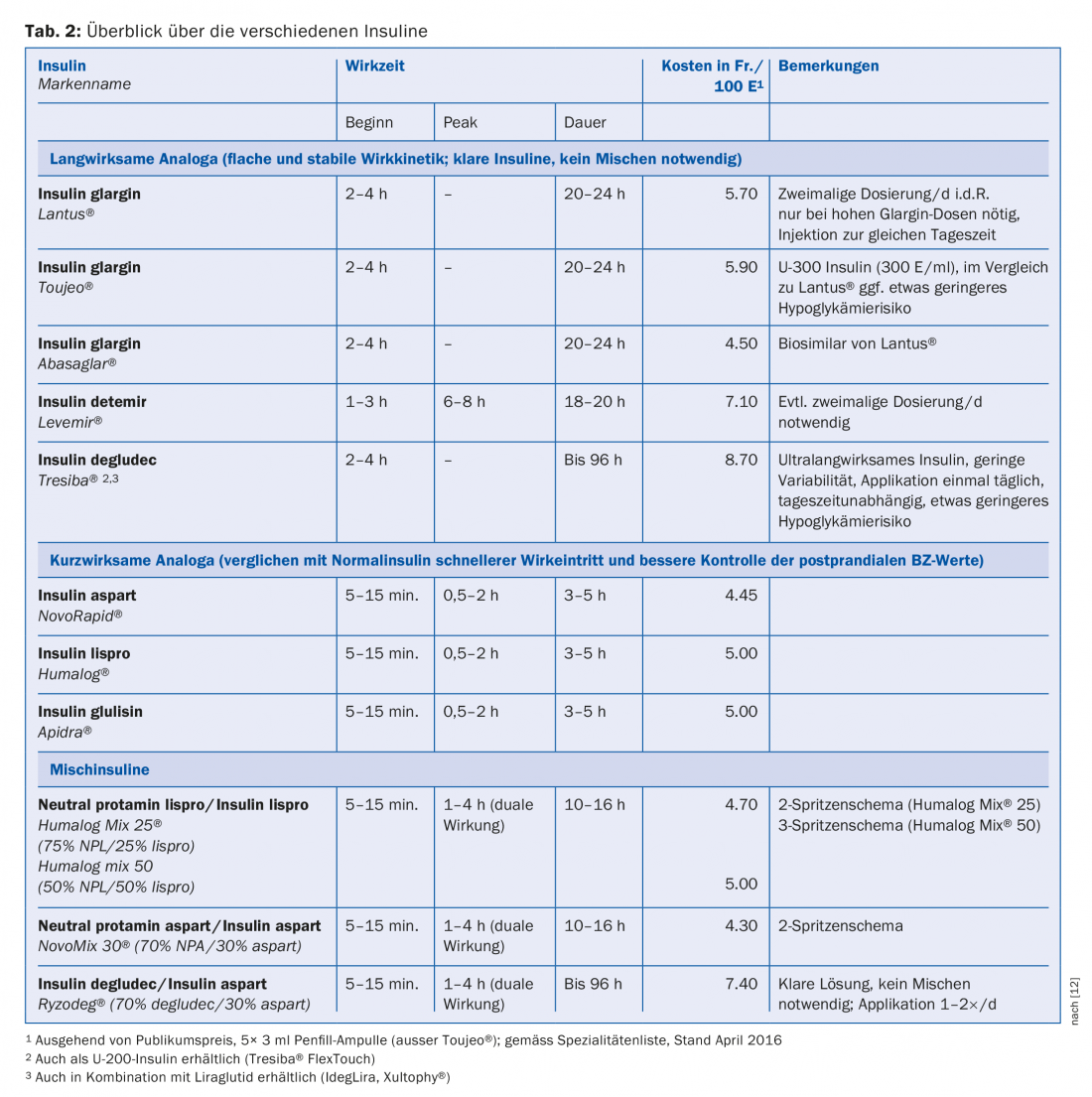

The different types of insulin

Based on the duration of action, insulins are divided into rapid-acting (prandial) insulins, long-acting (basal) insulins, and mixed insulins [12]. In a direct comparison, there are no differences in HbA1c reduction between insulin analogues and regular or NPH insulins. However, in everyday life and due to practical aspects (application, shorter injection-eating interval, better control of postprandial blood glucose levels, lower risk of hypoglycemia), insulin analogues have become established for both basal and prandial therapy. The analogues differ from human insulin by a modified molecular structure. By replacing certain amino acids or adding fatty acids, pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties such as duration of action or onset of action are altered. An overview of the insulin analogs (including mixed insulins) commonly used today is shown in Table 2.

General information on the practical implementation of insulin therapy

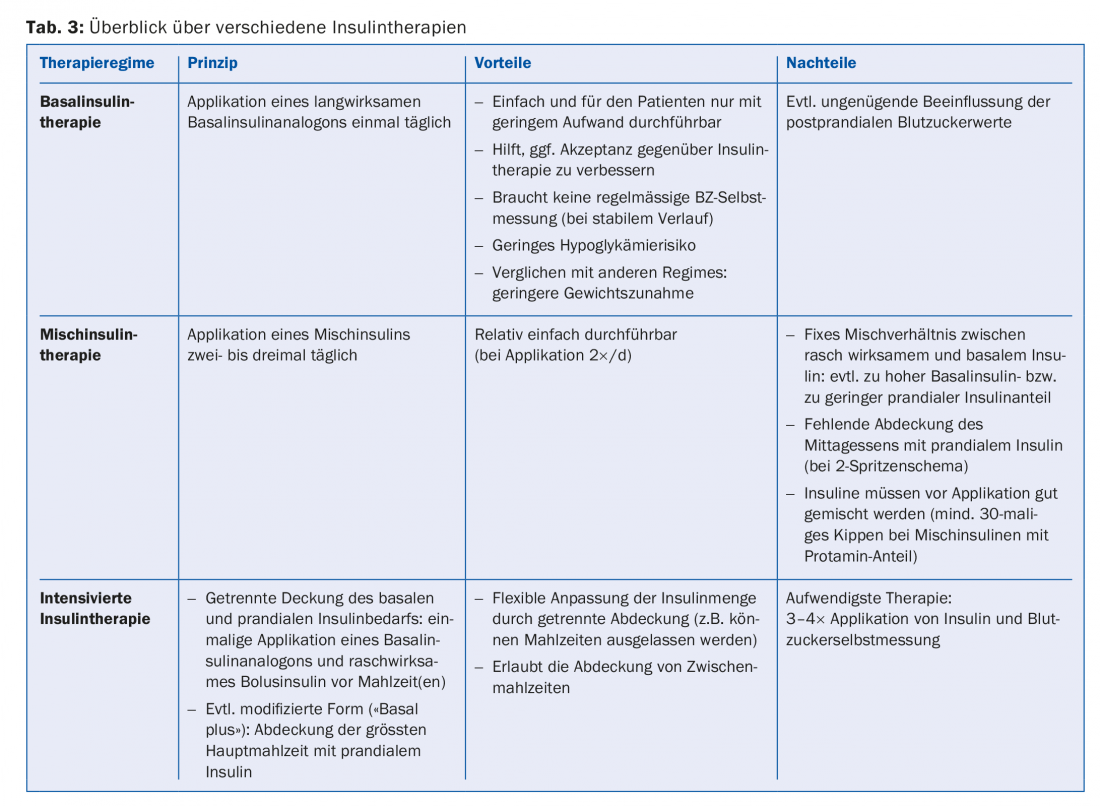

Ideal insulin therapy normalizes pre- and postprandial blood glucose levels without provoking hypoglycemia or weight gain. The known insulin regimens (Table 3) differ in their complexity and effort for the patient.

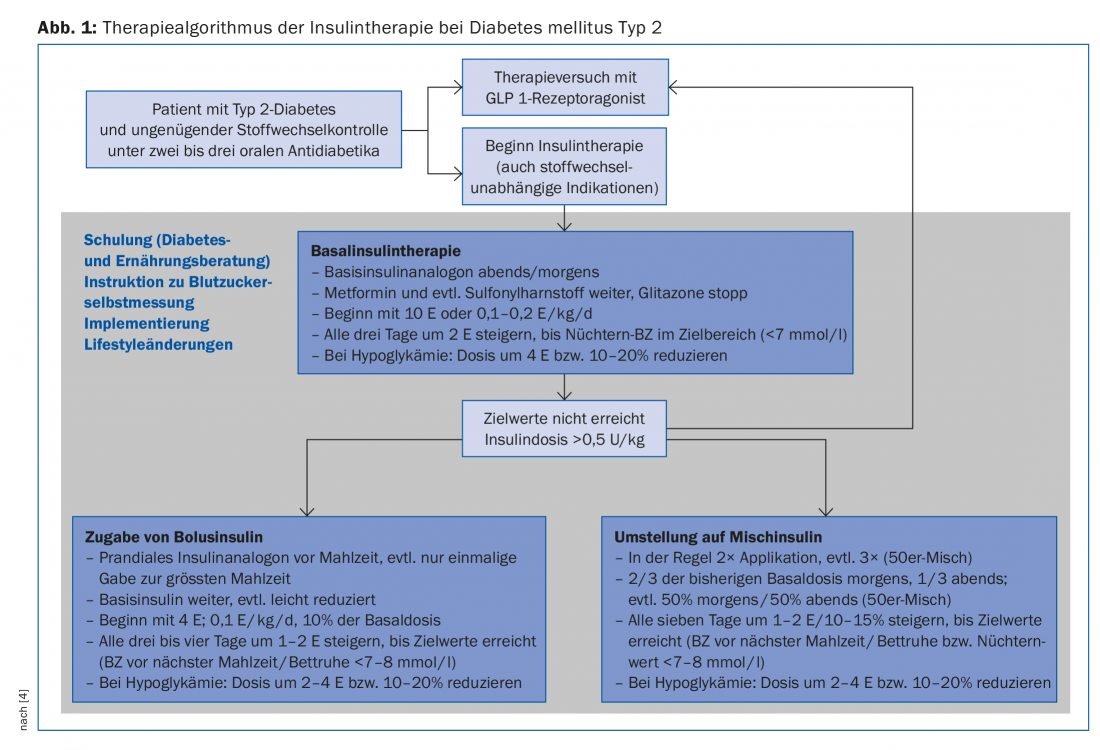

In a first step, therefore, basal insulin therapy is usually chosen, and only intensified if target values are not reached or insulin therapy deteriorates again (Fig. 1).

Motivation or adherence to therapy with injectable diabetes therapies is critical to treatment success. For the patient, insulin therapy often means a drastic change in the treatment concept; the therapy must be adapted to patient-specific resources and requires a considerable amount of training by an interdisciplinary team.

Side effects can significantly worsen adherence and must be avoided as much as possible from the beginning and discussed with the patient before starting therapy. The risk of hypoglycemia can be decisively reduced by dose adjustment and training (e.g. prevention of risk situations, reduction of insulin dose after physical exertion, slow dose titration). On the one hand, the weight gain is a reflection of improved metabolic control (reduced glucosuria), but it may also be due to other reasons, such as the intake of snacks to prevent hypoglycemia. In clinical practice, this side effect is probably one of the most frequent reasons for the failure of insulin therapy or one of the most important factors why insulin therapy is refused or started too late. The combination therapies with newer antidiabetic therapies – in addition to emphasizing the importance of lifestyle modification measures in this situation – can be additionally supportive here.

Basal insulin therapy

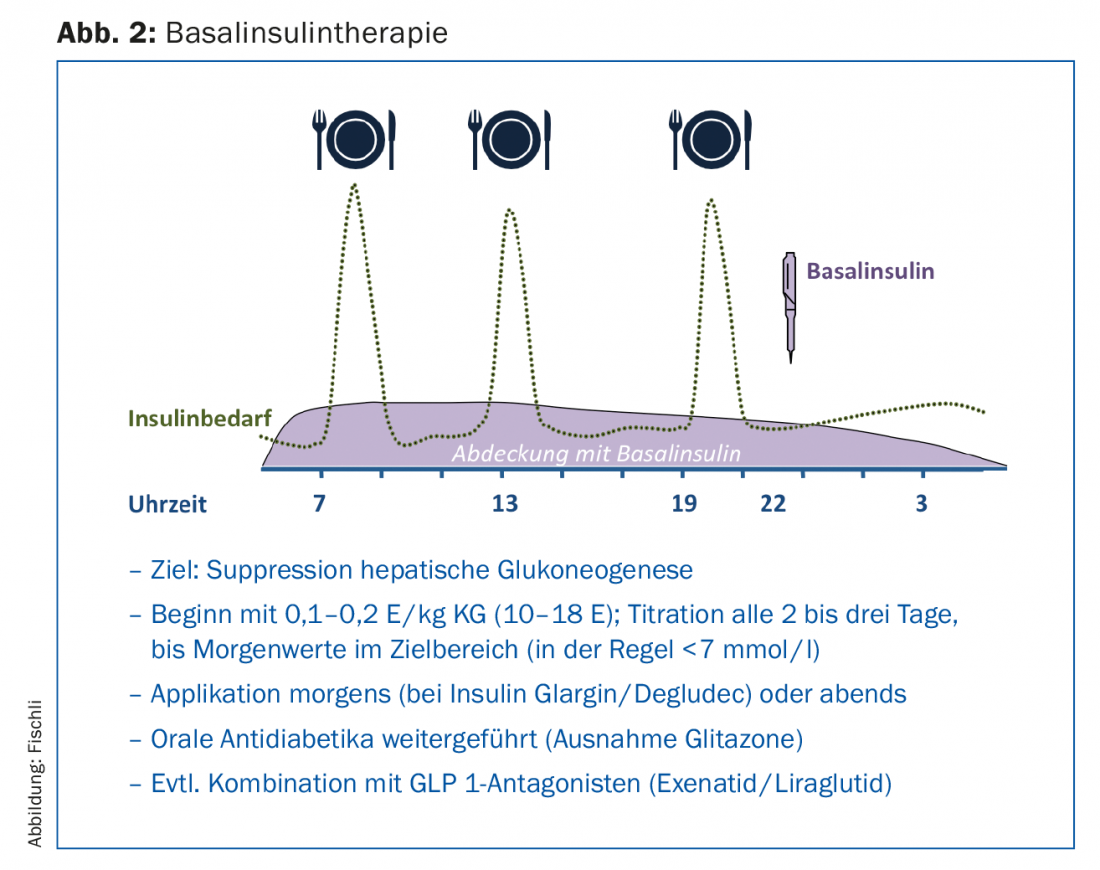

By far the easiest therapy to perform is basal insulin therapy (Fig. 2), which is performed as an add-on therapy to existing therapy with oral antidiabetic agents. The oral antidiabetic drugs, with the exception of glitazones, are usually passed, and in particular the combination with metformin has an insulin-sparing effect [13]. Sulfonylureas help control postprandial blood glucose levels, but they can increase the risk of hypoglycemia when combined with insulin. Moreover, they become increasingly ineffective with increasing diabetes duration and decreasing beta cell function.

Application of a long-acting basal insulin analogue primarily inhibits hepatic gluconeogenesis and thus reduces elevated fasting blood glucose levels as well as levels in the postabsorptive phase. With HbA1c values above 8.5%, high fasting blood glucose values in particular influence the metabolic situation [14], which is why basal insulin therapy decisively improves blood glucose control in these situations as well. In studies, glargine [15] or insulin detemir [16] in combination with metformin achieved an HbA1c value below 7% in about two-thirds of patients. When dosing, it should be noted that the insulin is gradually increased until the target values are reached (“treat to target” strategy). This increase can be done by the patient with appropriate training (Fig. 1).

Baseline insulin therapy offers the advantages of less weight gain and the smallest risk of hypoglycemia compared with prandial or mixed insulin therapy [17]. Especially for motor vehicle drivers, the latter point is crucial. In 2015, an interdisciplinary working group revised the guidelines regarding fitness to drive and driving ability in diabetes mellitus [18]. Individuals without risk factors (i.e., no hypoglycemia awareness disorder and no history of severe hypoglycemia) who are treated exclusively with a basal insulin analog (e.g., insulin glargine or detemir) have an overall low risk of hypoglycemia, which is why routine blood glucose monitoring before every car trip is now no longer necessary.

Combination with other antidiabetic agents

Combining insulin therapy with DPP IV inhibitors or GLP 1 receptor agonists is possible and offers several advantages [19]. Increasingly, the combination of insulin and GLP 1 analog is gaining acceptance. The sequence, i.e. which substance class is given first, does not really matter. Basal insulin may be started first, or insulin may be combined with GLP 1 receptor agonists as add-on therapy.

Pharmacologically, both substances have a blood sugar-lowering and synergistic effect via different mechanisms [20]. However, the influence of the GLP 1 receptor agonist on central appetite and satiety regulation helps to prevent weight gain under insulin therapy. A growing body of data now also supports the benefits of such combination therapy in terms of weight progression, metabolic control, and hypoglycemia risk [21].

In Switzerland, exenatide (Byetta®) and liraglutide (Victoza®) are approved for combination with basic insulin; liraglutide is also available as a fixed combination with insulin degludec (Xultophy®). The newer once-weekly dulaglutide (Trulicity®) is approved in combination with prandial insulin. The newest group of antidiabetic drugs, the SGLT 2 inhibitors, also has an insulin-sparing or weight-reducing effect when combined with insulin [22].

Intensification of insulin therapy

Intensification or modification of insulin therapy should be considered if metabolic control deteriorates further or side effects (hypoglycemia, weight gain) complicate therapy (Fig. 1). Before adding a prandial insulin or switching to a mixed insulin, it is worth trying a GLP 1 receptor agonist in combination with the basic insulin.

Intensification of insulin therapy is achieved either by adding a rapid-acting insulin analogue before meals as a classic baseline bolus regimen or by switching to a mixed insulin therapy. However, the latter has some disadvantages (Table 3), and in direct comparison with baseline bolus insulin, the mixed insulins perform worse in terms of metabolic control [23].

Literature:

- Polonsky WH, et al: Psychological insulin resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes: the scope of the problem. Diabetes Care 2005; 28(10): 2543-2545.

- Nakar S, et al: Transition to insulin in type 2 diabetes: family physicians’ misconception of patients’ fears contributes to existing barriers. J Diabetes Complications 2007; 21(4): 220-226.

- Romano G, et al.: Insulin and sulfonylurea therapy in NIDDM patients. Are the effects on lipoprotein metabolism different even with similar blood glucose control? Diabetes 1997; 46(10): 1601-1606.

- Inzucchi SE, et al: Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centered approach: update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2015; 38(1): 140-149.

- Holman RR, et al: 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008; 359(15): 1577-1589.

- Gerstein HC, et al: Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008; 358(24): 2545-2559.

- Patel A, et al: Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008; 358(24): 2560-2572.

- Duckworth W, et al: Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2009; 360(2): 129-139.

- Weng J, et al: Effect of intensive insulin therapy on beta-cell function and glycaemic control in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: a multicentre randomised parallel-group trial. Lancet 2008; 371(9626): 1753-1760.

- Harris MI, Robbins DC: Prevalence of adult-onset IDDM in the U.S. population. Diabetes Care 1994; 17(11): 1337-1340.

- Laugesen E, et al: Latent autoimmune diabetes of the adult: current knowledge and uncertainty. Diabet Med J Br Diabet Assoc 2015; 32(7): 843-852.

- Wallia A, Molitch ME: Insulin therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 2014; 311(22): 2315-2325.

- Hemmingsen B, et al: Comparison of metformin and insulin versus insulin alone for type 2 diabetes: systematic review of randomised clinical trials with meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses. BMJ 2012; 344: e1771.

- Monnier L, et al: Contributions of Fasting and Postprandial Plasma Glucose Increments to the Overall Diurnal Hyperglycemia of Type 2 Diabetic Patients Variations with increasing levels of HbA1c. Diabetes Care 2003; 26(3): 881-885.

- Riddle MC, et al: The treat-to-target trial: randomized addition of glargine or human NPH insulin to oral therapy of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2003; 26(11): 3080-3086.

- Hermansen K, et al: A 26-week, randomized, parallel, treat-to-target trial comparing insulin detemir with NPH insulin as add-on therapy to oral glucose-lowering drugs in insulin-naive people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006; 29(6): 1269-1274.

- Holman RR, et al: Three-year efficacy of complex insulin regimens in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2009; 361(18): 1736-1747.

- http://sgedssed.ch/fileadmin/files/6_empfehlungen_fachpersonen/61_richtlinien_fachaerzte/Neue-Auto-Richtlinien_SGED_15-11-24_DE-DEFkorr.pdf

- Yki-Järvinen H, et al: Effects of Adding Linagliptin to Basal Insulin Regimens for Inadequately Controlled Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2013; 36(12): 3875-3881.

- Del Prato S: Fixed-ratio combination of basal insulin and GLP-1 receptor agonist: is two better than one? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014; 2(11): 856-858.

- Eng C, et al: Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist and basal insulin combination treatment for the management of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2014; 384(9961): 2228-2234.

- Nauck MA: Update on developments with SGLT2 inhibitors in the management of type 2 diabetes. Drug Des Devel Ther 2014; 8: 1335-1380.

- Giugliano D, et al: Efficacy of insulin analogs in achieving the hemoglobinA1c target of <7% in type 2 diabetes: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care 2011; 34(2): 510-517.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(5): 8-14