The treatment of pain in paraplegic patients takes into account various causes of pain [1–4]. The success of drug, neurosurgical, interventional, and other therapeutic approaches is currently limited. A multimodal therapeutic approach is therefore mandatory.

Traumatic paraplegia is relatively rare, with an incidence of 3 cases per 100 000 in Switzerland [5]. Nevertheless, a particularly large number of patients in this patient group suffer from chronic pain (prevalence 81%). Pain symptomatology is very complex in patients with traumatic paraplegia, as different causes of pain often occur in the same patient. Thus, 59% of patients reported musculoskeletal pain, 41% reported neuropathic pain at lesion level or 34% reported neuropathic pain below lesion level, and 5% reported visceral pain. 58% of patients report severe and excruciating pain. There does not appear to be a correlation between the presence of neuropathic pain and the extent of injury such as complete or incomplete spinal cord lesion [6].

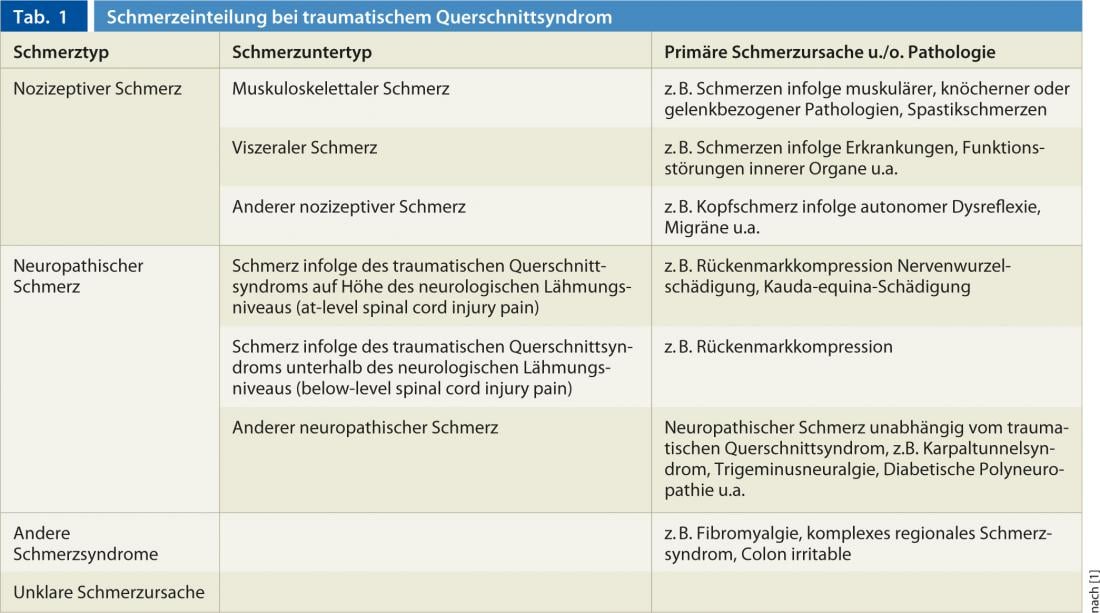

Classification of pain in traumatic paraplegic syndrome.

In 2002, the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) proposed for the first time a uniform classification for pain after traumatic spinal cord lesion. This classification has now been revised by the International Spinal Cord Society and published as a new consensus classification for pain after spinal cord lesion. Accordingly, a distinction is made between nociceptive, neuropathic, other defined pain syndromes, and unclassifiable pain (Tables 1 and 2) [1]. In neuropathic pain associated with traumatic paraplegic syndrome, the neurologic level of injury plays an important role. This is defined as the most caudal dermatome with normal sensitivity to light touch and pointed sensation or the myotome with normal motor function. According to the new classification mentioned above, the English-language terms such as at-level spinal cord injury pain (at-level SCIP) for pain in the dermatome of the neurological injury level including the three underlying dermatomes as well as the English-language term below-level spinal cord injury pain (below-level SCIP) are currently also used in the German-speaking world.

Whereas at-level SCIP can be of central neuropathic origin in spinal cord injury as well as of peripheral neuropathic origin in e.g. traumatic nerve root damage at the level of the injury, below-level SCIP is by definition a centrally generated neuropathic pain due to spinal cord lesion. Neuropathic pain in cauda equina syndrome represents a special form, since this corresponds to a peripheral neuropathic cause of pain due to nerve root damage of the cauda epuina and is therefore classified by definition in the group of at-level SCIP, even if the pain extension beyond three segments is found below the neurological paralysis level.

Role of instrumental diagnostics

According to the IASP, neuropathic pain is defined as pain caused by a lesion or disease affecting the somatosensory system [7]. In this case, in addition to the above-mentioned anamnestic and clinical features, the lesion of the somatosensory system that explains the neuropathic pain should also be demonstrated by apparatus. The diagnosis of traumatic paraplegic syndrome is predominantly made on the basis of imaging. Here, lesions in the spinal cord can usually be found both in patients with and without chronic pain after traumatic paraplegia. In this case, clinical neurophysiology is of secondary importance in the diagnosis of at-level or below-level SCIP, since patients without pain also show pathological neurophysiological findings concerning the spinal cord. Currently, it is still unclear which patients with traumatic paraplegia develop pain and which do not. In individual cases, for example, in patients with pain in spinal cord lesion without traumatic cause such as MS, cervical myelopathy, spinal cord ischemia, etc., neurophysiology may be helpful to support the diagnosis of neuropathic pain after spinal cord lesion.

A recent paper shows that the newer neurophysiological methods such as Laser Evoked Potentials (LEP) and Quantitative Sensory Testing (QST) show a higher hit rate compared to the conventional method of Somatosensory Evoked Potentials (SEP). For example, LEP (functional test for the spinothalamic tract) was pathological in seven of eight examinations, while QST showed pathological findings of the spinothalamic tract in five of eight examinations, and additionally pathological findings concerning the posterior cord in three of eight examinations. The SEP as a functional test for the posterior cord was pathological in only two of eight examinations and is therefore of limited significance [8].

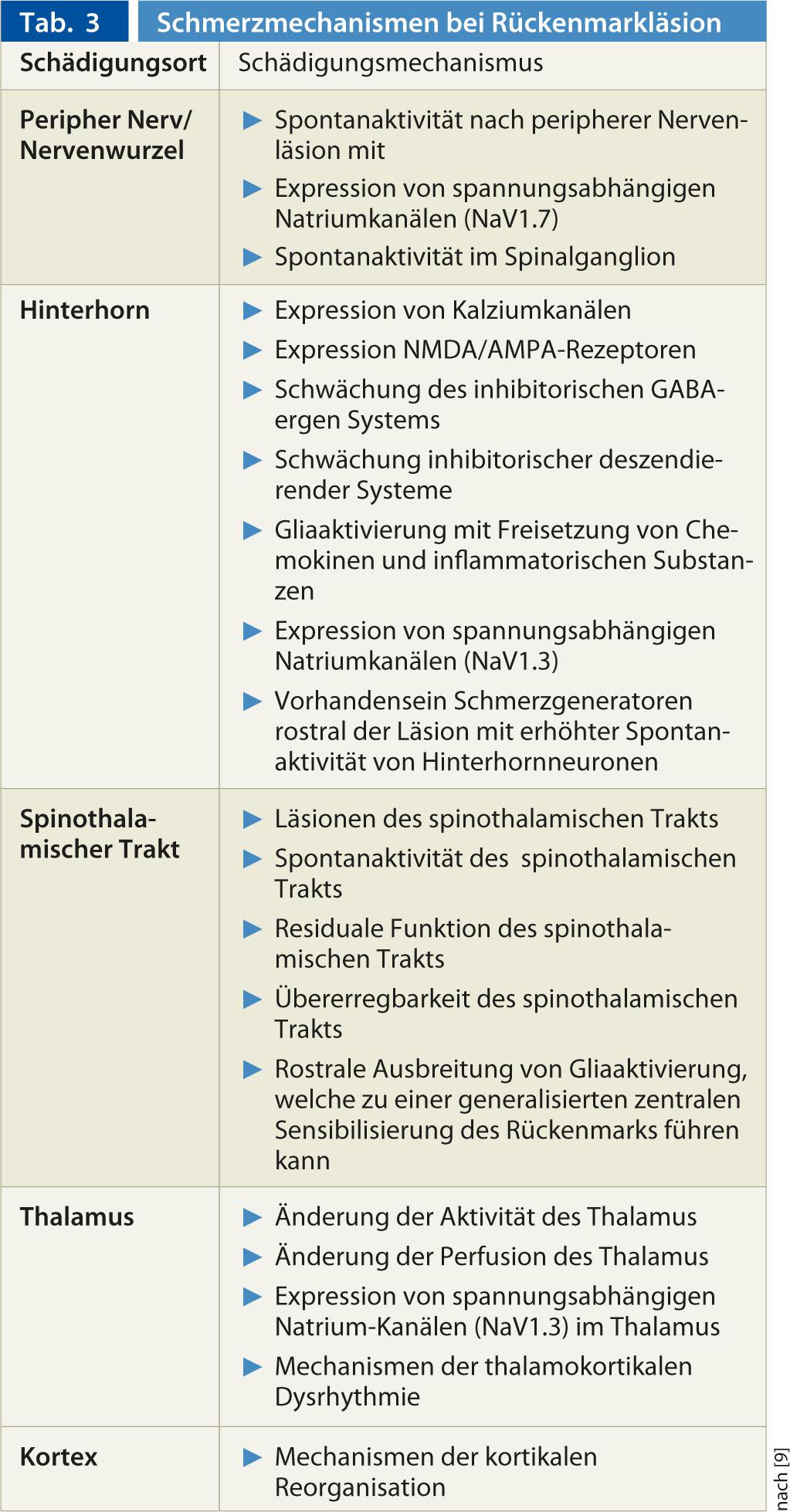

Mechanisms of pain development of neuropathic pain after paraplegia.

The recent review by Finnerup et al. 2012 [9] provides a good overview of neuropathic pain mechanisms in spinal cord lesion (Table 3). In addition, central processes may also be affected by changes in peripheral nociceptive nerves (e.g., when nerve roots are injured at the level of neurological damage): After such a lesion of a peripheral nerve, various pathophysiological mechanisms may occur that can lead to peripherally generated neuropathic pain. Nerve injury results in the appearance of ectopic spontaneous activity in the nerve fibers or spinal ganglion. This spontaneous activity reflects increased expression of voltage-gated sodium channels (e.g., NaV 1.7). The ongoing spontaneous activity may further lead to peripheral sensitization of the nerve fiber, for example, by expression of TRPV1 receptors at the free nerve terminals.

Therapeutic approaches to pain after traumatic paraplegic syndrome.

According to Siddall 2009 [10], pain is considered a significant factor in suffering, poorer rehabilitation outcome, and decreased quality of life in patients with traumatic paraplegic syndrome. According to the different possible causes of pain explained above, the treatment of pain after traumatic paraplegia is always interdisciplinary and multimodal. Regarding nociceptive pain, according to the musculoskeletal pathology, mainly orthopedic (e.g. therapy of shoulder pathologies), physiotherapeutic (e.g. treatment of muscular pain factors) and occupational therapy (e.g. adjustment of the sitting position of the wheelchair) measures are involved. In addition to oral spasticity therapy, the placement of an intrathecal spasticity pump may be necessary. Internal medicine is indicated for visceral pain.

The experience that multimodal pain therapy with somatic, physical and psychological exercise as well as psychotherapeutic procedures is superior to monodisciplinary procedures in chro¬nic pain syndromes without paraplegia should also be taken into account in the therapy of chronic pain in traumatic paraplegia [11]. Promising studies on cognitive behavioral therapy or imagined walking methods are available, although the current data situation is inconsistent [10].

Drug therapy approaches

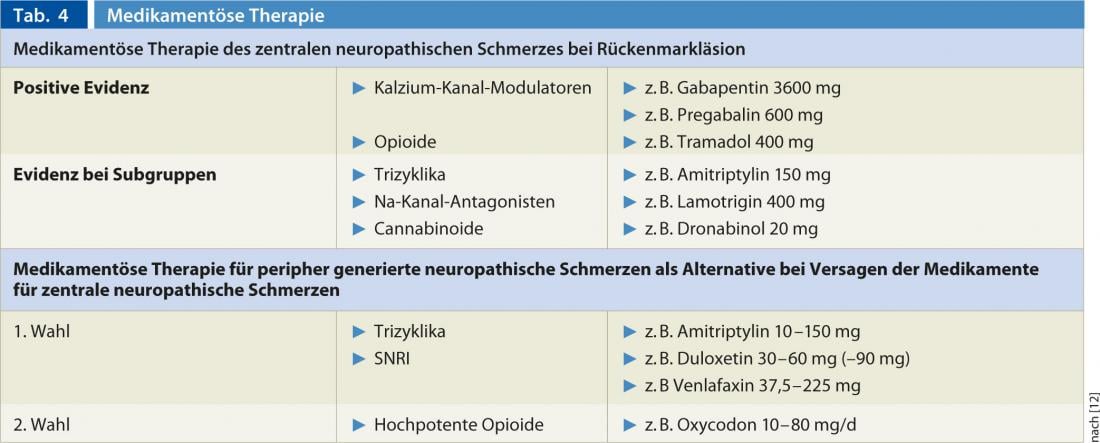

Drug therapy approaches for neuropathic pain after traumatic paraplegic syndrome have been evaluated in international guidelines such as the guideline of the Neuropathic Pain Working Group of the International Pain Society (NeuPSIG) [12] or the guideline of the European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNS) [13]. The drugs mentioned there are in principle also suitable for central neuropathic pain syndromes that do not have a traumatic origin, such as spinal cord lesions due to MS or spinal cord ischemia. The large number of drugs listed in Table 3 The lack of a common therapy for the mechanisms mentioned above at different neuronal levels and systems may explain why the response of drugs available for the therapy of neuropathic pain in traumatic paraplegia is limited: For a large number of the mechanisms, no therapy is available yet.

For the treatment of centrally caused neuropathic pain in traumatic paraplegia, calcium channel modulators such as gabapentin and pregabalin and the opioid tramadol show positive evidence of efficacy. Regarding pregabalin, the NNT is 3.9 for a 30% reduction in pain. In contrast, tricyclics were effective only in a subgroup with depression at the dose of 150 mg daily. Lamotrigine was effective in a subgroup with incomplete spinal cord lesion and allodynia. Cannabinoids can be used in MS, but due to the possible risk of psychosis, they should only be used after other therapies have failed (Table 4). If sufficient pain reduction cannot be achieved with the above-mentioned drugs, it is recommended to switch to the drugs of the 1. and 2nd choice for the treatment of peripherally generated neuropathic pain [12]. These include al™hl the highly potent opioids such as MST, Oxycontin, and other opioids. The use of these groups of medications may also be useful primarily because, for example, in at-level SCIP, peripheral neuropathic pain mechanisms are also a not insignificant pain precipitant.

Neurosurgical and interventional therapeutic approaches

Despite a variety of drug therapy options, these are often unsatisfactory [13]. Only about 30-40% of patients with neuropathic pain show satisfactory drug response [14]. According to Dworkin et al. 2007 [15] invasive methods may be attempted after conservative individual or combined therapeutic procedures have been exhausted. The current data regarding neurosurgical and interventional therapeutic approaches are compiled in recent reviews [9, 10]. The evidence for all of the above procedures is limited and each requires experienced centers for evaluation regarding such procedures.

Neurosurgical therapeutic approaches such as dorsal root entry zone lesioning (DREZ, elimination of overactive neurons within the posterior horn, close to the lesion level) and corpectomy (anatomic transection of the spinal cord) have been studied only in small case series and are performed only in rare individual cases. The use of a spinal cord stimulator (SCS) may lead to improvement, and a greater effect can be expected in at-level SCIP and in incomplete lesions. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is highly invasive and has a questionable long-term effect. Transcranial motor cortex stimulation (rTMS) and epidural motor cortex stimulation (MCS) have been performed in single cases with SCIP with variable results.

A new therapeutic method for patients with neuropathic pain including neuropathic pain in traumatic paraplegia was described by Martin et al. 2009 [16] described. In this procedure, high-intensity focused ultrasound is used to thermally ablate a circumscribed area of the centrolateral thalomus transcranially in a noninvasive manner, which can lead to pain relief.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- Pain in patients with traumatic paraplegia can have a variety of causes.

- Nociceptive pain such as musculoskeletal pain, spasticity-associated pain, and visceral pain may occur.

- Neuropathic pain underlies a variety of mechanisms at the level of the spinal cord, including at the level of the thalamus and cortex.

- Neuropathic pain associated with traumatic paraplegic syndrome may be at or below the neurologic injury level (at-level spinal cord injury pain or below-level spinal cord injury pain/SCIP).

- The multitude of different causes of pain often makes an interdisciplinary clarification and multimodal pain therapy necessary.

- Calcium channel modulators and tramadol are available with good evidence for drug therapy of central neuropathic pain. Tricyclics and lamotrigine are useful only in subgroups.

- Interventional therapies have been poorly evaluated and are reserved for centers.

Literature list at the publisher