Since the first description of a pancreatic resection by the Königsberg surgeon Walter Kausch in 1909, pancreatic surgery has developed into an interdisciplinary center treatment. Pancreatic surgery is the only chance of cure for patients with pancreatic cancer. Early detection of the disease and rapid initiation of individualized multidisciplinary treatment are crucial. New radiological techniques, neoadjuvant and adjuvant (radio)oncological treatments, and improved perioperative care in highly specialized centers provide the critical foundation for therapeutic success.

With an incidence of approximately 10/100,000 inhabitants per year, pancreatic cancer represents the fourth to fifth most common cause of cancer-related death in industrialized countries, and the trend is rising. While mortality is improving for many malignancies, pancreatic cancer remains one of the deadliest cancers despite new treatment approaches. Pancreatic cancer is expected to be the leading cause of cancer death by 2025.

The treatment difficulty arises from the aggressive biology of the tumor with early metastasis as well as late diagnosis with prolonged absence of symptoms. This is responsible for the fact that only 20% of patients with pancreatic cancer have any chance of being cured. Overall 5-year survival rates just approach 5% for pancreatic cancer. In patients in whom surgery is feasible, the 5-year survival rate increases to more than 20% [1]. The focus should therefore be on prevention and early detection of the disease, preferably at an early stage or as a precursor lesion, and rapid connection of the affected patient to a specialized center.

Early detection

Early detection of pancreatic cancer is a major challenge. There is a lack of screening tests as well as programs for systematic early detection. It is crucial that early warning clinical symptoms are recognized in a timely manner by the primary care physician. The Swiss Pancreas Foundation therefore relies on awareness programs and provides fact sheets (www.pankreasstiftung.ch).

Possible symptoms such as weight loss, reduction in general condition, nonspecific abdominal complaints, and unexplained back pain due to infiltration of retroperitoneal nerve plexuses must make one think of pancreatic carcinoma. New-onset diabetes mellitus and classically painless jaundice may also occur as initial manifestations. If a malignancy is detected early and can be completely removed, a 5-year survival rate of 50% is possible in the case of favorable tumor biology [2].

An important prognostic factor is tumor size at diagnosis. Therefore, during radiological examinations, it is important to monitor even the smallest lesions or cystic tumors in the pancreas as they may already be carcinoma or its precursor. Tumor markers alone are unsuitable as a screening test because no specific tumor antigens are known to date. However, in combination with history, clinic, and radiologic examination, tumor markers can be helpful in the evaluation.

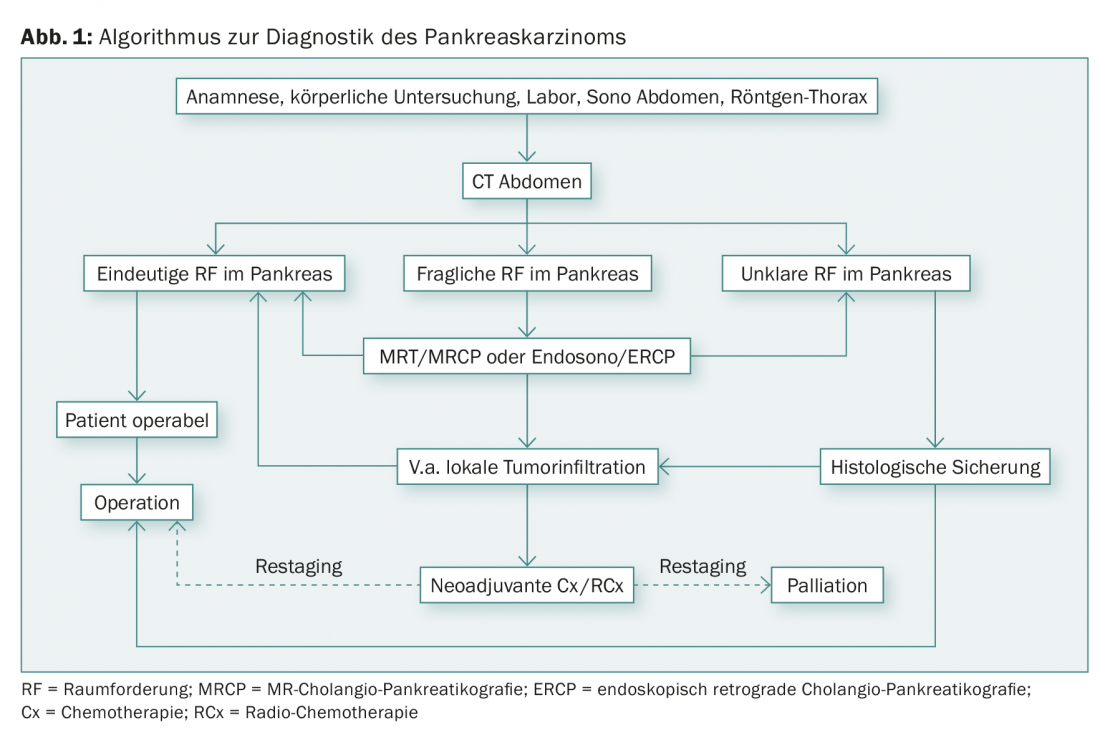

Diagnostic algorithm

Sonography, as a simple and inexpensive examination, can confirm bile duct obstruction. However, evaluation of the organ is often difficult due to its retroperitoneal location. For resectability assessment and staging, computed tomography of the thorax and abdomen is the gold standard [3].

Magnetic resonance imaging in combination with angio-MRI and MRCP (=magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticography) can help differentiate cystic pancreatic tumors and questionable liver metastases.

Endosonography can complement other imaging modalities. Small tumors in particular can be well differentiated. At the same time, endosonographically guided fine-needle biopsy is the best method of histological confirmation, e.g. before palliative chemotherapy. Routine biopsy before resection is not recommended.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography (ERCP) is highly valued because of its diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities (stenting). Preoperative stent placement to relieve the congested bile ducts is increasingly controversial. A randomized trial from the Netherlands found higher perioperative complication rates in patients with preoperative biliary drainage compared with patients with immediate surgery [4]. Therefore, it is important to consult a specialized surgeon early in cases of bile duct obstruction to determine the best therapeutic regimen on an interdisciplinary basis. Diagnostic laparoscopy is used in cases of suspected peritoneal carcinomatosis (ascites, very high CA-19-9 level) or liver metastasis. In approximately 30% of cases, findings are made that exclude curative resection.

Of the known serum markers in pancreatic tumors (CA 19-9, CEA, and NSE), CA 19-9 has the highest sensitivity (80%) with a specificity of 75% for carcinoma. It should be noted that an elevated level of CA 19-9 may also be associated with cholestasis. Also, CA 19-9 depends on Lewis blood group antigens: CA 19-9 is not expressed in antigen a- and b-negative patients (5-7% of the population). Figure 1 shows an overview of the diagnostic workup for suspected pancreatic cancer.

Operational risk

Surgical therapy remains the only potential cure for patients with pancreatic cancer. High-risk resection should be performed in interdisciplinary centers with appropriate expertise to minimize perioperative morbidity and mortality. In this context, both surgical and oncologic outcomes depend significantly on the number of cases [5]. Postoperative morbidity is approximately 40% in experienced centers [6]. The main postoperative problems are fistulas (5-30%), bile leaks (0.4-8%), postoperative bleeding (1-8%), and delayed gastric emptying with difficult food buildup (19-23%), which is usually reversible after 14 days. Relaparotomy is required in approximately 5% of cases. Successful pancreatic surgery can thus only be achieved through good complication management. This is where the experience of the surgeon in collaboration with anesthesiologists, gastroenterologists, and interventional radiologists plays a critical role. The mortality rate after pancreatic surgery is 2-4% in reference centers.

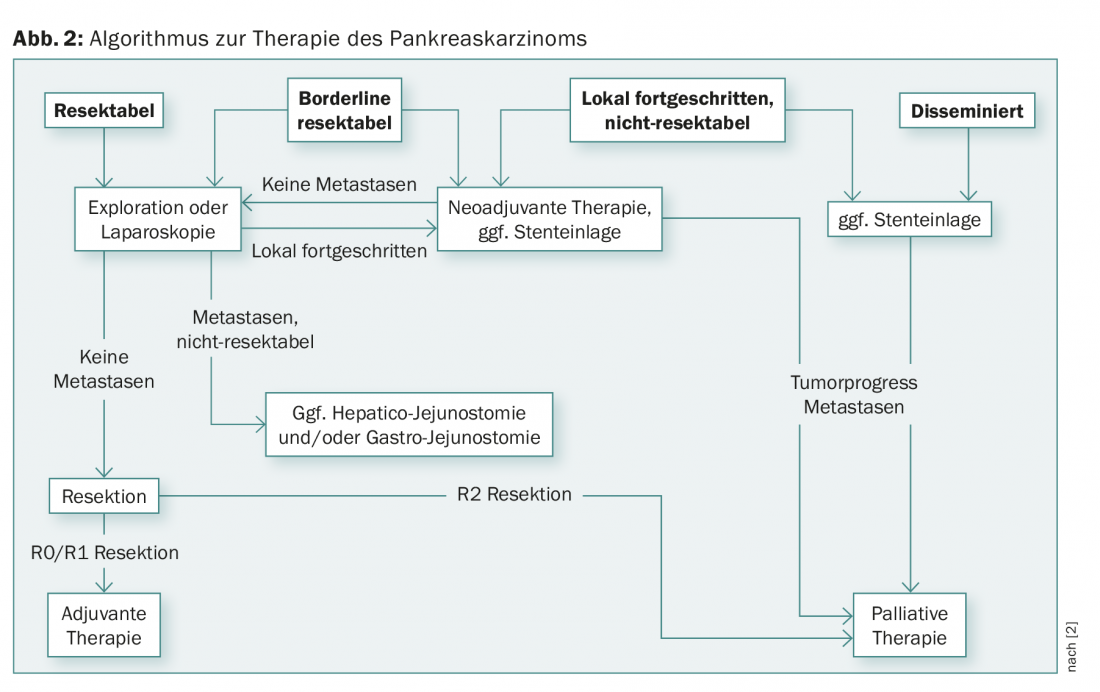

Pancreatic Surgery

In the majority of pancreatic cancer patients, distant metastasis is present at the time of diagnosis, so that only palliative therapy is possible. Tumors of the pancreas that are localized and do not show vascular infiltration and distant metastasis are considered resectable. Locally advanced pancreatic cancer should be discussed in an interdisciplinary manner regarding multimodality therapy. In each individual case, a balance is made between primary resection and neoadjuvant pretreatment (chemotherapy or radio-chemotherapy) (Fig. 2) [7].

Locally advanced tumors often infiltrate the portal vein, the superior mesenteric artery, or the coeliac trunk. In contrast to arterial resection, venous resection (portal vein or superior mesenteric vein) can be performed at specialized centers with comparable morbidity and mortality to pancreatic resection without vascular resection [8]. In selected individual cases, arterial resection can also be performed with curative intent, but this is associated with high perioperative morbidity and mortality [9].

Curative therapy

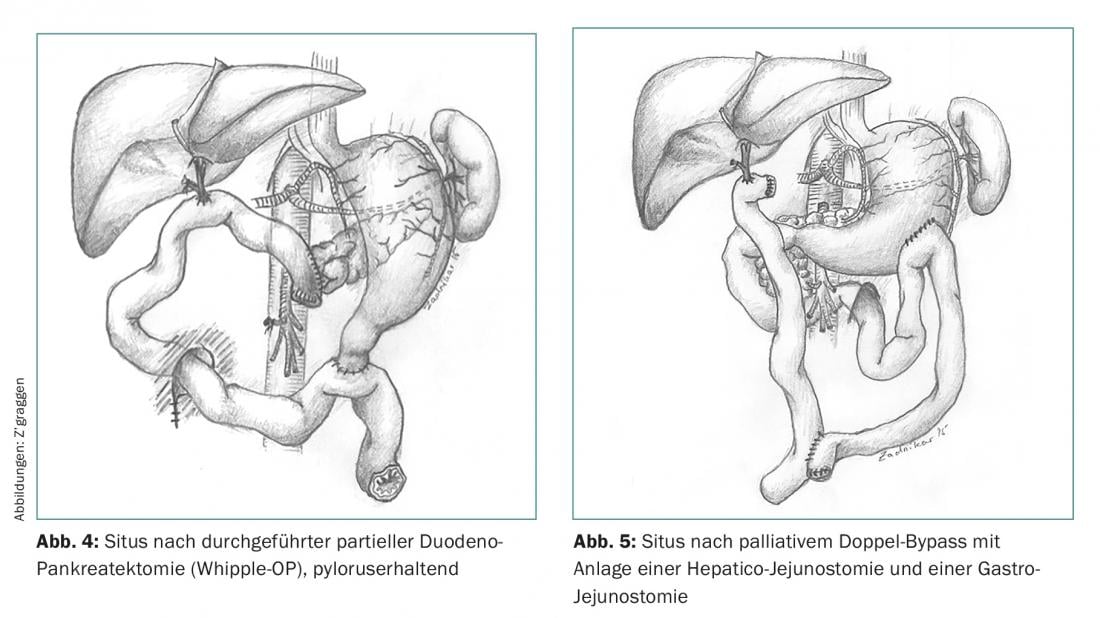

Resection of a tumor in the head of the pancreas requires a partial duodeno-pancreatectomy (Whipple operation) (Fig. 3), which can be performed either classically with entrainment of the distal stomach or with pylorus preservation (Fig. 4). Distal pancreatic carcinomas are operated on via en bloc resection of the pancreatic tail, taking along the spleen to complete the lymphadenectomy. A third therapeutic option, particularly for locally advanced pancreatic cancer or extensive or multiple precursor lesions (e.g., IPMNs), is total pancreatectomy. Because lymph node involvement is a strong prognostic factor, standard lymphadenectomy is always performed during oncologic pancreatic surgery.

Palliative therapy

Palliative therapy of pancreatic cancer is the domain of systemic chemotherapy. Endoscopic or surgical interventions are often required due to tumor-related bile duct and/or duodenal stenosis. In any case, the choice of procedure (stent vs. surgery) should be made on an interdisciplinary basis depending on the patient’s general condition. If a contraindication to the planned Whipple operation (distant metastasis) arises during surgical exploration of a pancreatic carcinoma, the creation of a “double bypass” for palliation is recommended (Fig. 5).

Aftercare

For symptom-free patients (well-being, no pain, no weight loss), no follow-up is established after pancreatic resection. Nevertheless, it is useful to examine patients clinically on a regular basis (e.g., every three to six months) and to perform a laboratory check of initially pathological parameters.

Malnutrition and maldigestion

Pre- and perioperatively, many patients lose significant weight [10]; this weight loss can often be insufficiently compensated postoperatively. Causes of lack of weight gain include recurrence of pancreatic cancer, inadequate caloric intake, food intolerances, or exocrine pancreatic insufficiency.

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency

The dosage of digestive enzymes depends on the severity of the insufficiency and the fat content of the food. As a rule of thumb, one can start with 2000 lipase units per gram of dietary fat and continue to increase the dose as symptoms persist. Daily dosage should not exceed 15,000-20,000 lipase units per kg body weight. The enzyme preparation must be taken during meals. For efficacy, it should be noted that gastric acid is normally neutralized by the bicarbonate formed in the pancreas. If this neutralization is omitted, the food pulp in the intestine remains acidic. This leads to impaired activity of pancreatic enzymes, including those substituted with drugs. Proton pump inhibition (PPI) should be discussed. In addition, it should be considered that in patients with gastric resection or taking PPI, the lack of or insufficient alkalinization dissolves the acid protection incompletely or delayed, so that the drugs cannot develop their effect sufficiently. In this case, either the administration of non-acid-protected pancreatic enzymes is required or the patient opens the capsule and takes the contents during the meal.

Furthermore, so-called pancreaticocibial asynchrony occurs after both classic and pylorus-preserving duodeno-pancreatectomy. This means that although the pancreatic enzymes are secreted at the right time, they do not come into contact with the chyme until the mid-jejunum because of the absence of the duodenum; they run behind the chyme, so to speak. In addition, there is the so-called “ileal break”, a release of the hormones GLP-1 and PYY induced by the rapid passage of food into the ileum, which leads to an inhibition of pancreatic secretion and a decrease in appetite [11].

Vitamin and iron deficiency

Continued alcohol consumption, marked exocrine insufficiency, and/or severely restricted fat intake may cause a deficit of fat-soluble vitamins [12]. To prevent deficiency states that would lead to osteoporosis and osteomalacia in the long term, as well as visual and skin changes, annual monitoring of vitamin levels and, if necessary, substitution is necessary. Detection is possible by determination of 25-OH vitamin D3 in serum. Vitamin K deficiency can be estimated by the INR. Serum levels of vitamins A and E are unfortunately unreliable; measurement of β-carotene may be useful. Taking vitamins in tablet form only makes sense if they are safely absorbed. If a classic Whipple operation with antrectomy was performed, a monthly intramuscular injection of vitamin B12 may be necessary. Any iron deficiency (lack of duodenal absorption) must usually be substituted parenterally.

Endocrine pancreatic insufficiency

Postoperatively, pancreopriver diabetes mellitus may manifest. This may also develop with a delay, so HbA1c follow-up is indicated every three to six months.

Literature:

- Neoptolemos JP, et al: Adjuvant chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus folinic acid vs gemcitabine following pancreatic cancer resection. A randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Ass 2010; 304: 1073-1081.

- Hartwig W, et al: Pancreatic cancer surgery in the new millennium. Better prediction of outcome. Ann Surg 2011; 254: 311-319.

- Callery MP, et al: Pretreatment assessment of resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Expert consensus statement. Ann Surg Oncol 2009; 16: 1727-1733.

- van der Gaag NA, et al: Preoperative biliary drainage for cancer of the head of the pancreas. N Engl J Med 2010; 362(2): 129-137.

- Gooiker GA, et al: Systematic review and meta-analysis of the volume-outcome relationship in pancreatic surgery. Br J Surg 2011; 98: 485-494.

- Hüttner FJ, et al: Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (pp Whipple) versus pancreaticoduodenectomy (classic Whipple) for surgical treatment of periampullary and pancreatic carcinoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016.

- Werner J, et al: Advanced-stage pancreatic cancer: therapy options. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2013; 10(6): 323-333.

- Müller SA, et al: Vascular resection in pancreatic cancer surgery. Survival determinants. J Gastrointest Surg 2009; 13(4): 784-792.

- Mollberg N, et al: Arterial resection during pancreatectomy for pancreatic cancer. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg 2011; 254(6): 882-893.

- Bachmann J, et al: Cachexia worsens prognosis in patients with resectable pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 2008; 12: 1193-1201.

- Maljaars PW, et al: Ileal brake. A sensitive food target for appetite control. A review. Physiol Behav 2008; 95: 271-281.

- Marotta F, et al: Fat-soluble vitamin concentration in chronic alcohol-induced pancreatitis. Relationship with steatorrhea. Dig Dis Sci 1994; 39: 993-998.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2016; 4(2): 34-38.