Just over a year ago, a consensus statement from two European societies shook up the position of fasting lipid measurement. Concerns about lipid determination in the non-sober state appear largely unfounded.

The consensus statement of two European societies (EAS/EFLM) [1] has shaken the “holy grail” of fasting lipid measurement a good year ago. Rationale: Concerns about lipid determination in the non-fasted state are largely unfounded. According to the authors, data from recent registry and cohort studies demonstrate that prior dietary intake affects the lipid profile only to a small extent and is usually not clinically significant. This was also shown for fasting and non-fasting measurements in the same patients. In addition, non-fasting lipid levels appear to reflect cardiovascular risk equally well or even better: A prospective analysis from the Women’s Health Study with a median follow-up of over eleven years shows that triglyceride levels two to four hours postprandial have the strongest association with cardiovascular events, whereas with longer food abstinence the association becomes progressively weaker [2].

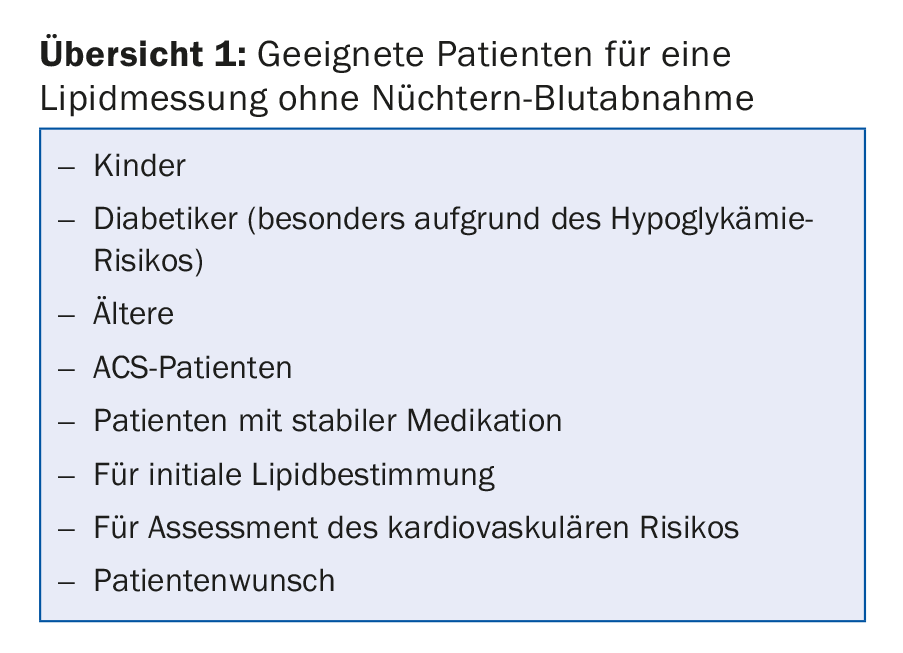

Both patients and physicians should be pleased with the new recommendations, as they represent a considerable simplification of measurement. “Particularly for certain groups of people, staying sober can be a burden,” says Prof. Arnold von Eckardstein, MD, University Hospital Zurich. “I am thinking here of diabetics, for example.” Lipid measurement does not necessarily have to be performed in the morning and especially not in a separate, next appointment, which saves time (also for physician decision-making) and improves patient compliance.

Thus, while fasting lipid measurement is no longer indicated for the vast majority of patients (overview 1), it cannot be completely written off. If the paper is followed, the two measurement methods complement each other rather than being mutually exclusive. For example, a fasting withdrawal is certainly justified in the case of:

- non-fasting triglyceride levels >5 mmol/l (440 mg/dl)

- Known hypertriglyceridemia with subsequent referral to a lipid clinic.

- Recovery after hypertriglyceridemia-induced pancreatitis.

- Planned therapy with drugs that could induce severe hypertriglyceridemia.

- other blood tests that must be performed fasting, e.g. determination of fasting blood glucose.

Limits

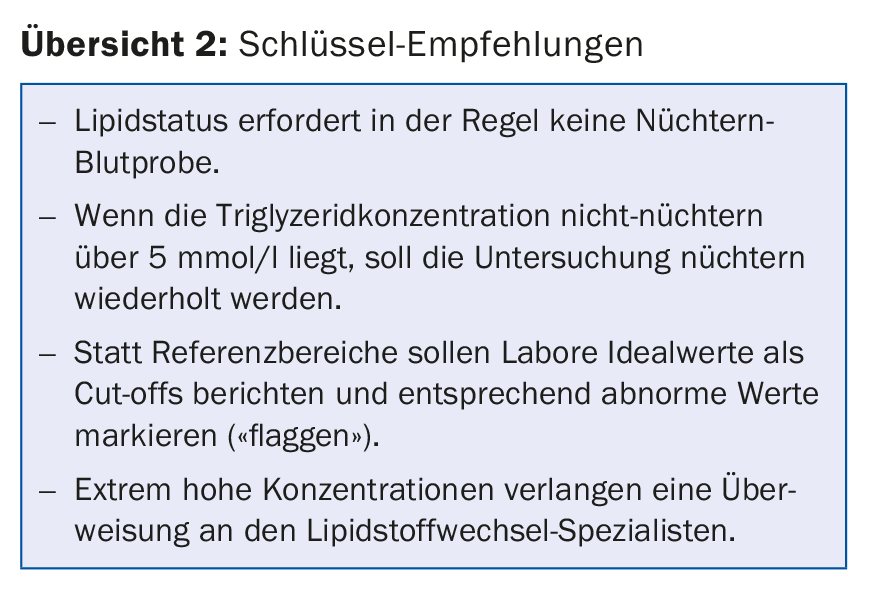

The EAS/EFLM consensus also recommends using the target values of current guidelines rather than traditional laboratory reference values, i.e., for nonfasting profiles, the following limits are judged to be abnormally high:

- Triglycerides: ≥2 mmol/l

- Total cholesterol: ≥5 mmol/l

- HDL cholesterol: ≤1 mmol/l

- LDL cholesterol: ≥3 mmol/l

- Non-HDL cholesterol: ≥3.9 mmol/l

Compared to the fasting value, the cut-off value for triglycerides has been increased by 0.3 mmol/l (based on the mean deviation in studies with non-fasting values).

According to the paper, referral to a specialist is necessary for extreme readings, for example, triglycerides ≥10 mmol/l, LDL-C ≥13 mmol/l, or Lp(a) ≥150 mg/dl.

Overview 2 summarizes again the most important findings of the consensus.

Use of different lipid parameters

Depending on the purpose (screening, diagnostics, risk monitoring, treatment goals), the different lipid parameters are differently suitable [3].

If one wants to assess the general cardiovascular risk, primarily LDL cholesterol is recommended. Similarly, total cholesterol and HDL cholesterol should be used (“strongly recommended”), as well as triglycerides and non-HDL cholesterol (“recommended”). The TC/HDL-C ratio is not recommended. Worth considering is ApoB. An analysis

of lipoprotein(a) may be useful in risk groups.

Total cholesterol is insufficient for diagnosis and stratification. Primary recommended here is also LDL-C, alongside HDL-C, triglycerides and non-HDL-C (“recommended”). ApoB and, in risk groups, lipoprotein(a) may also be considered.

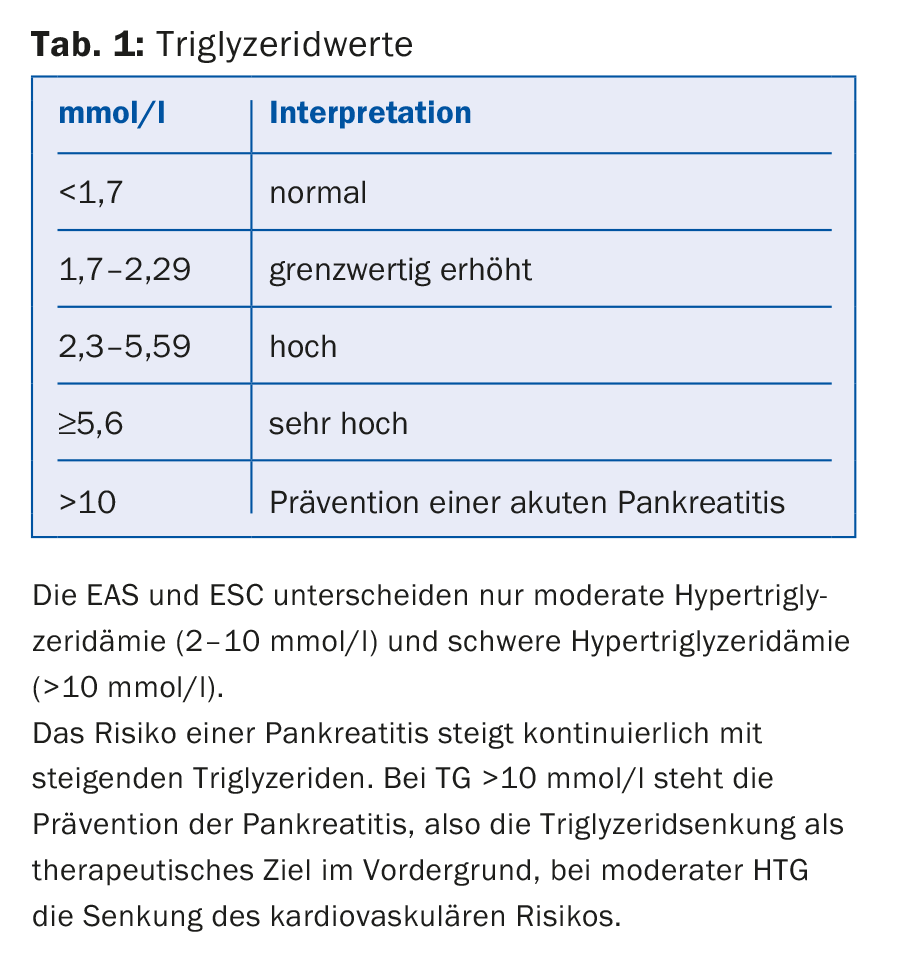

Finally, only LDL-C is actually needed for therapy monitoring or for the treatment goals. If this is not available, total cholesterol can also serve as a surrogate lipid parameter. HDL-C or the ratio TC/HDL-C or ApoB/ApoA-I are not recommended. Non-HDL-C and ApoB can be considered, in addition triglycerides in case of hypertriglyceridemia (HTG, Tab. 1).

Hypertriglyceridemia

“In hypertriglyceridemia, secondary causes should be considered first” said Prof. Nicolas Rodondi, MD, Inselspital Bern. “These include alcohol consumption, diabetes, obesity, and chronic renal failure. Regarding medication, consider estrogens, thiazides, beta blockers, or corticosteroids, for example.”

Hypertriglyceridemia is responsible for about one-tenth of all cases of acute pancreatitis; alcohol and gallstone disease are far more important precipitating factors, accounting for more than 80%. Etiologic confounding may result from the simultaneous presence of two predisposing factors in the same individual. Specific triglyceride limits do not exist in this context; in general, concentrations of at least 10 mmol/l are associated with increased risk (arbitrary). However, only about one-fifth of individuals with such levels develop pancreatitis. Moreover, it may well occur when values are lower (below 5-10 mmol/l), as a recent study showed [4].

Moreover, one should not forget the cardiovascular risk that hypertriglyceridemia may entail (especially in women) [5]. As mentioned, the non-fasting lipid profile seems to better reflect cardiovascular risk in this regard than the fasting one [2]. The ESC/EAS guidelines recognize hypertriglyceridemia as a significant independent risk factor (although the association is weaker than for hypercholesterolemia). The risk is particularly associated with moderate hypertriglyceridemia – even more so than with severe forms with over 10 mmol/l. Unfortunately, the evidence base is insufficient to derive specific triglyceride target values.

With regard to management, non-drug approaches are in the foreground, and these include the classics:

- Reduction of alcohol consumption

- Dietary recommendations

- Daily physical activity

- Weight reduction or at least stabilization.

At levels below 5.5 mmol/l, the efficacy of drug interventions on cardiovascular events is not clear. At higher levels, the above measures (acutely also low-fat diet with no more than 15% of total calories) and fibrates, if necessary, are used to prevent acute pancreatitis. Familial dyslipidemia should be excluded.

Source: SGK/SGHC Annual Meeting, June 7-9, 2017, Baden.

Literature:

- Nordestgaard BG, et al: Fasting is not routinely required for determination of a lipid profile: clinical and laboratory implications including flagging at desirable concentration cut-points – a joint consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society and European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. Eur Heart J 2016; 37(25): 1944-1958.

- Bansal S, et al: Fasting compared with nonfasting triglycerides and risk of cardiovascular events in women. JAMA 2007; 298(3): 309-316.

- Catapano AL, et al: 2016 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidaemias. Eur Heart J 2016; 37(39): 2999-3058.

- Pedersen SB, Langsted A, Nordestgaard BG: Nonfasting mild-to-moderate hypertriglyceridemia and risk of acute pancreatitis. JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176(12): 1834-1842.

- Nordestgaard BG, et al: Nonfasting triglycerides and risk of myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, and death in men and women. JAMA 2007; 298(3): 299-308.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(7): 30-32

CARDIOVASC 2017; 16(4): 38-40