Monkeypox is not a new disease. The first confirmed human case dates to 1970, when the virus was isolated in a child suspected of having smallpox in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Monkeypox is unlikely to cause another pandemic, but given the COVID-19 virus, the fear of another large outbreak is understandable. Although monkeypox is rare and usually mild, it can still lead to severe illness. As a result, health officials are concerned that more cases will occur as travel increases.

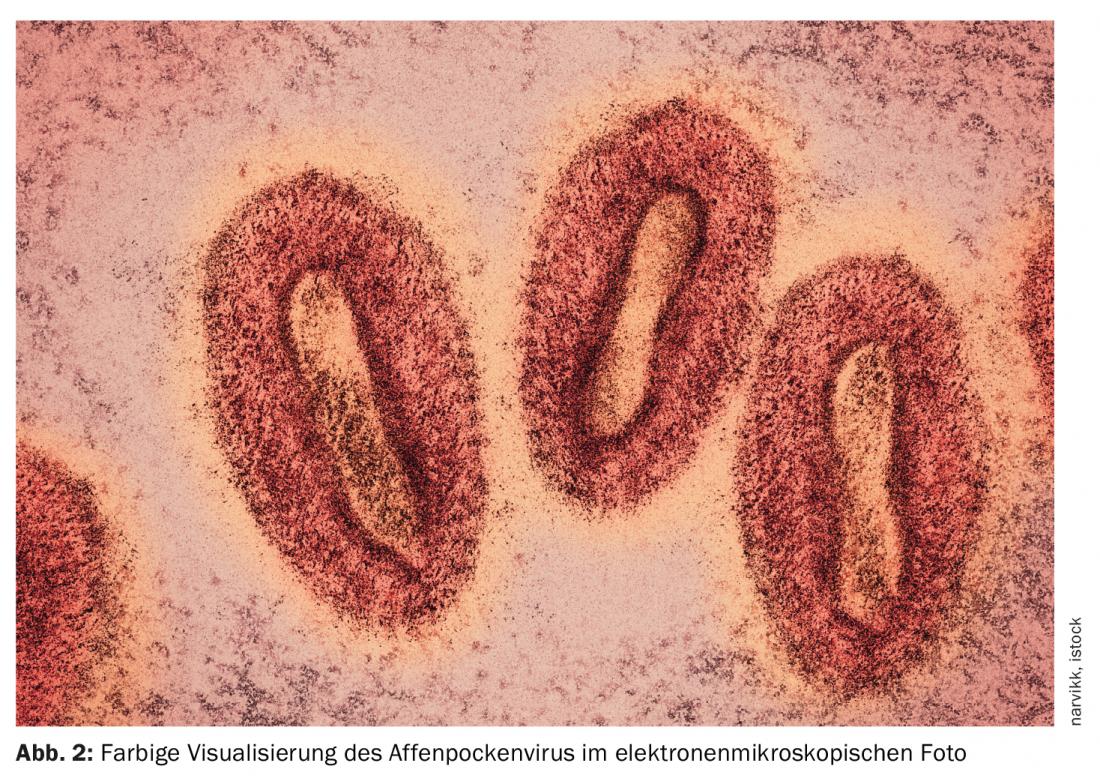

Monkeypox is caused by the monkeypox virus, which belongs to a subgroup of the Poxviridae family called Orthopoxvirus. This subgroup also includes the smallpox, vaccinia, and cowpox viruses. An animal reservoir for monkeypox virus is not known, but African rodents are thought to play a role in transmission. It has only been isolated twice in nature from an animal. Diagnostic tests are currently available only at Laboratory Response Network laboratories in the U.S. and worldwide.

The name “monkeypox” comes from the first documented cases of the disease in animals in 1958, when two outbreaks occurred in monkeys kept for research. However, the virus has not jumped from monkeys to humans, and monkeys are not considered the primary carriers of the disease.

Epidemiology

Since the first reported human case, monkeypox has been detected in several other Central and West African countries, with most infections occurring in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Cases outside Africa have been associated with international travel or imported animals. The first reported cases of monkeypox in the United States occurred in 2003 in an outbreak in Texas that was linked to a shipment of animals from Ghana. Travel-associated cases also occurred in Maryland in November and July 2021.

Because monkeypox is closely related to smallpox, the smallpox vaccine can protect against infection with both viruses. Officially, however, smallpox has been eradicated, which is why routine smallpox vaccinations for the general population in Switzerland were discontinued in 1972. For this reason, monkeypox is increasingly occurring in unvaccinated individuals.

Transmission

The virus can be transmitted through contact with an infected person or animal or through contaminated surfaces. It usually enters the body through injured skin, inhalation, or through the mucous membranes in the eyes, nose, or mouth. Researchers believe that person-to-person transmission occurs primarily through inhalation of large droplets from the air we breathe, rather than through direct contact with body fluids or indirect contact through clothing.

- Contact with infected secretions, blood, or large respiratory droplets,

- close contact with infected humans or animals, usually through skin or mucosal contact (eyes, nose, mouth, genitals, etc.),

- Contact with contaminated objects, for example with clothes, bed linen, hygiene articles,

- sexual contact with an infected person (increased likelihood of person-to-person transmission).

Diagnostics

Laboratory diagnosis by PCR is indicated when monkeypox infection is suspected. Collection of a specimen by smear or biopsy of skin florescences (exudate, pustule contents, crusts, etc.) should be sent to the national reference center for emerging viral infections (CRIVE in Geneva):

Contact number 079 553 09 22 (24/7);

https://www.hug.ch/laboratoire-virologie/formulaires-informations

Shipped in category B UN 3373 (triple packed).

Signs and symptoms

After the virus enters the body, it begins to replicate and spread throughout the body via the bloodstream. Symptoms usually do not appear until one to two weeks after infection. Monkeypox causes smallpox-like skin lesions that are usually milder than smallpox. Initially, flu-like symptoms are common, ranging from fever and headache to shortness of breath. One to ten days later, a rash may appear on the extremities, head or trunk, eventually turning into pus-filled blisters. Overall, symptoms last about two to four weeks, while skin lesions disappear after 14 to 21 days.

Symptoms at a glance:

- Headache

- Acute onset fever (>38.5 C)

- Lymphadenopathy (swollen lymph nodes)

- Myalgia (muscle and body pain)

- Back pain

- Asthenia (pronounced weakness)

- Acute exanthema: usually one to three days (possibly longer) after the onset of fever. As a rule, this typically begins on the face with spread to the entire body including hands, feet and, if necessary, genitals. First mostly macules, then development of papules, vesicles, pustules and finally crusts.

Although monkeypox is rare and generally nonfatal, a variant of the disease causes death in about 10% of those infected. The currently circulating form of the virus is considered milder and has a mortality rate of less than 1%.

Isolation for persons tested positive

Positively tested person must isolate themselves at home. Isolation lasts until the crusts fall off over the skin lesions and a new skin layer is formed, i.e. at least ten days, and can be extended by the competent cantonal authority if necessary (for example, crusts fall off later). Affected persons receive the necessary instructions and information on isolation from the cantonal physician. This person also carries out contact tracing and instructs the contact persons of suspected cases or persons who have tested positive.

Vaccines and treatments

Treatment of monkeypox focuses primarily on symptom relief. Currently, there are no treatments available to cure monkeypox infection. People with weakened immune systems are particularly at risk.

Because smallpox is closely related to monkeypox, the smallpox vaccine can protect against both diseases. Evidence suggests that the vaccine may help prevent smallpox infections and reduce the severity of symptoms. A third-generation vaccine for immunization against smallpox in adults (MVA-BN/Imvanex®) was licensed in Europe and the United States. This offers good protection against monkeypox, but is not yet approved in Switzerland. The possible procurement of vaccines is currently being clarified.

According to current knowledge, the use of condoms does not fully protect against monkeypox infection because transmission occurs through contact with skin lesions.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2022; 17(6): 18-19