Chronic hepatitis C is one of the most common causes of advanced liver disease and liver transplantation in Switzerland. For people with chronic HCV infection, however, the situation has improved significantly in recent years, as high cure rates can be achieved with new drugs. At the 55th Continuing Medical Education Course in Davos, Prof. Dr. med. Markus Heim, University Hospital Basel, presented the current therapy guidelines – and also the reasons why experts are not entirely happy with the current approval status of the new active substances.

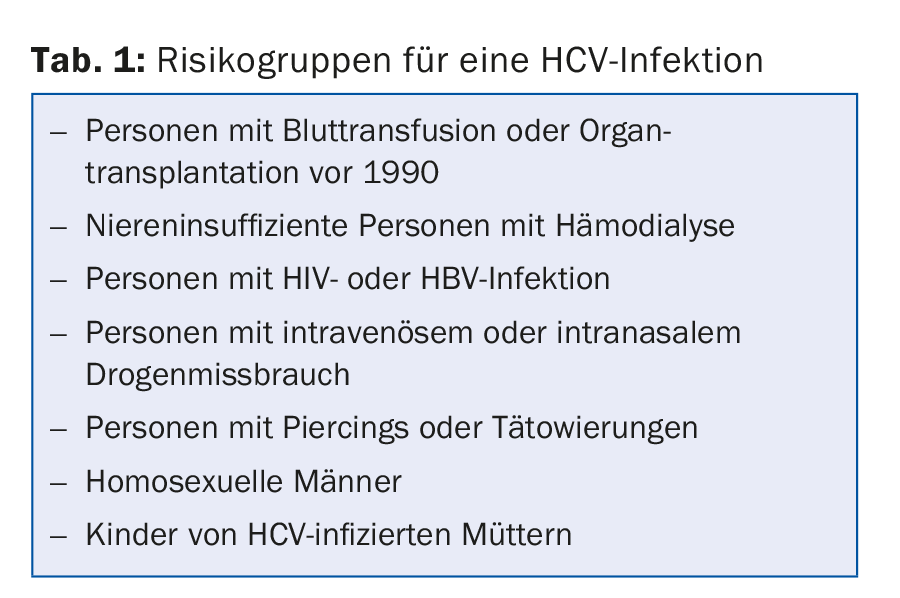

In Switzerland, between 70,000 and 100,000 people are infected with hepatitis C, but only about half of those affected know about it. Hepatitis C is most common among the “baby boomer” cohorts (now 40- to 60-year-olds). In about two-thirds of infected individuals, hepatitis C becomes chronic, and in 20-50% of these individuals the disease is progressive. This means that cirrhosis of the liver develops over the decades and hepatocellular carcinoma in about 5%. HCV antibody testing is recommended not only for clinical or laboratory evidence of hepatitis C, but also for members of at-risk groups (Table 1).

Therapy of chronic hepatitis C in upheaval

Cure rates have been steadily increasing for chronic hepatitis C over the past 25 years. In the 1990s, when interferon was the only treatment available, the cure rate was 15-20%, but with the addition of various antiviral agents, it has increased to 75% in recent years. In the last year, several active ingredients have now been approved in Switzerland that have good tolerability and excellent efficacy. “In some groups of patients, the rate of viral eradication is 99-100%,” Markus Heim emphasized. These antiviral agents are always administered in combination, but without interferon, because of the possible development of resistance.

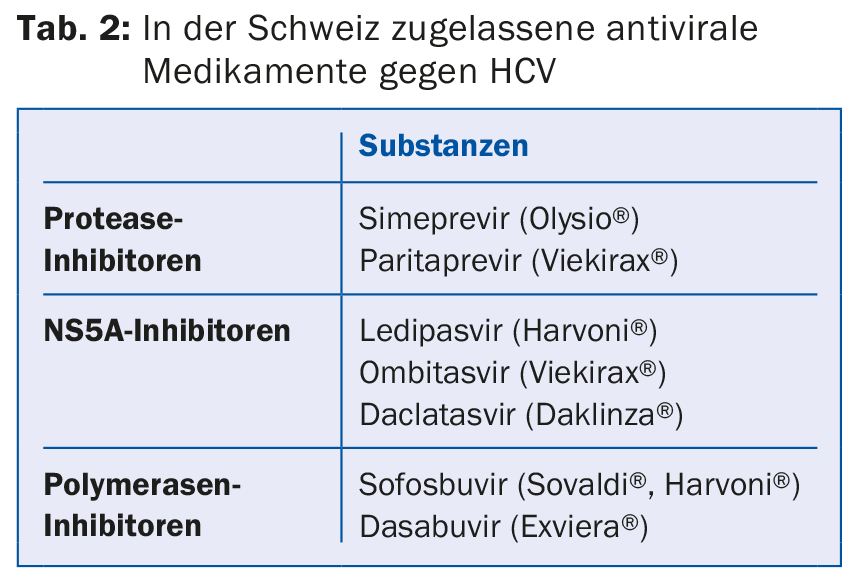

The new agents are divided into three groups (Table 2), depending on which enzyme or protein of viral metabolism they inhibit. Which agents are taken in which combination and with which duration of therapy depends on the genotype of HCV, the stage of cirrhosis and the pretreatments.

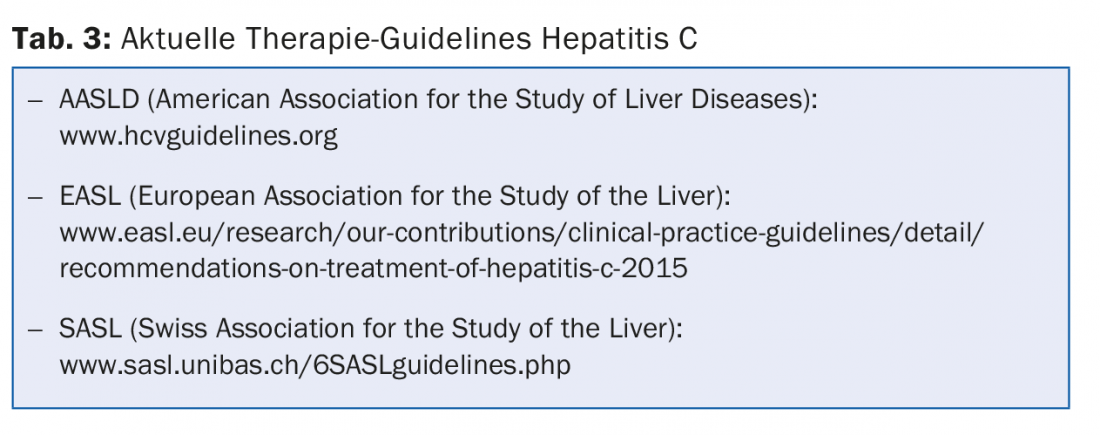

“The relevant guidelines are complicated and constantly changing,” the speaker said. “That’s why you always have to update yourself before you start therapy.” Various websites with the American, European and Swiss recommendations serve this purpose (Tab. 3). In principle, the European guidelines would apply to Switzerland, but since the approvals in Switzerland do not correspond to those in the rest of Europe, Swiss guidelines had to be drawn up.

Limitations – not always useful

Because the new drugs are expensive, the FOPH has introduced some very complex limits on prescribing. This includes that treatments may only be performed by specialists with experience in hepatitis C therapy.

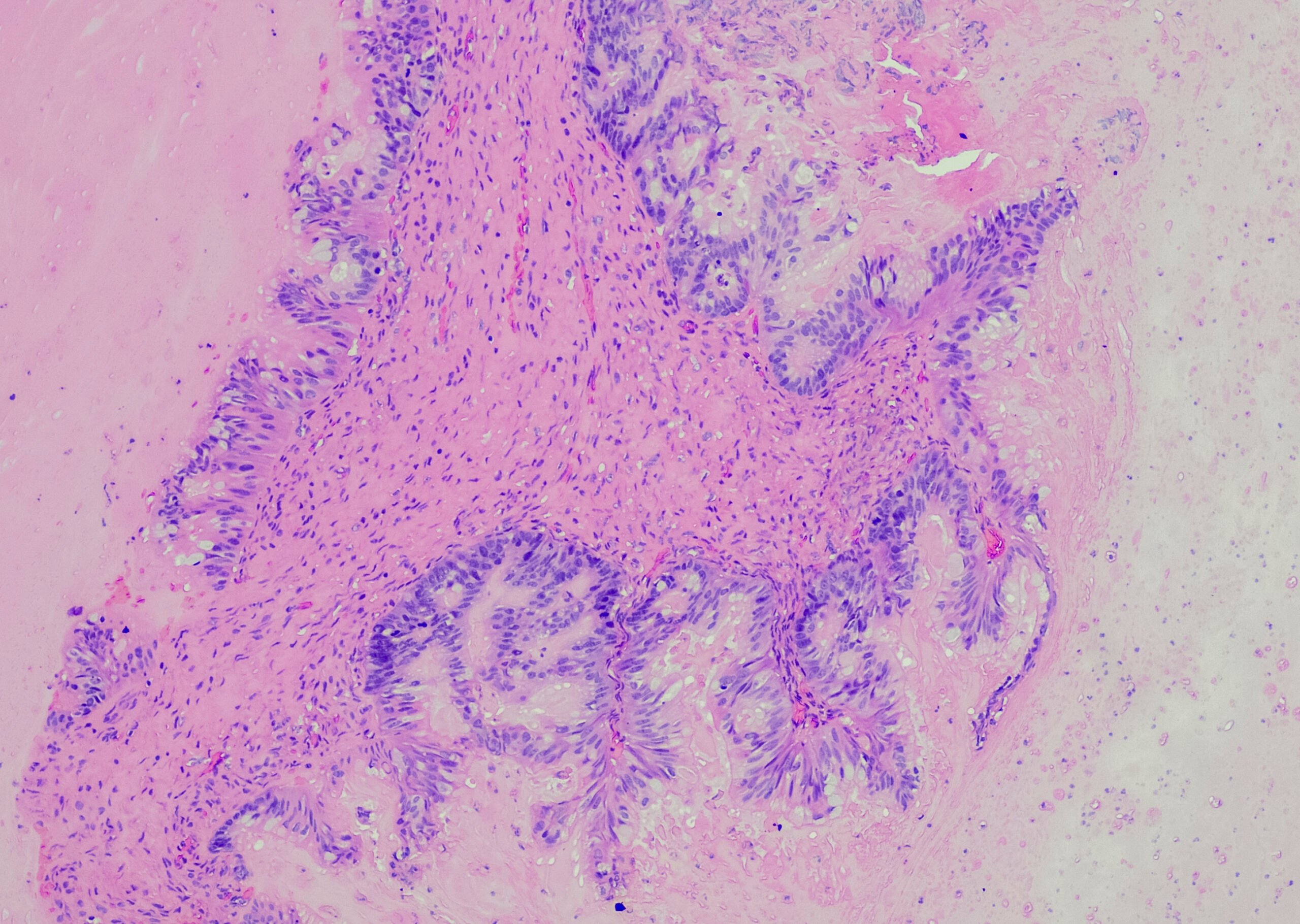

Currently, only patients with advanced liver fibrosis can be treated with the new compounds (stages F2-F4; F2 = moderate, F3 = severe, F4 = cirrhosis). Therefore, the degree of fibrosis must be determined before starting therapy, either with a liver biopsy or fibroscan (noninvasive measurement of liver stiffness). “Both methods have their weaknesses and inaccuracies,” the speaker said. Fibrosis does not always affect the entire liver equally, so non-fibrotic tissue may be obtained during a biopsy even though advanced fibrosis is actually already present. Liver stiffness is also quite variable: for example, patients with stage 2 may have the same stiffness score as patients with stage 3 liver fibrosis. This has concrete implications: “The current cut-off value of 7.5 kPa means that up to two-thirds of all patients with fibrosis stage 2 cannot be treated because their stiffness value is below that.”

Patients with HCV infection after organ or stem cell transplantation may be treated as early as fibrosis stage F0 – but only with Harvoni®. This is only approved for infected individuals with HCV genotype 1. This means that HCV-infected transplant patients with a different genotype cannot be treated. For the speaker, this is an absurd situation: “We have to wait for liver fibrosis to develop in these patients for the therapy to be paid for by health insurance.”

Why treat at all?

Because of the high costs and the great effort, the question arises now and then why the patients should be treated at all. But there are enough medical reasons for that:

- The reduction of inflammation stops the fibrosis process. In some patients, the degree of fibrosis even decreases after eradication.

- Eradication reduces the risk of liver cancer by 70%.

- Eradication reduces mortality from liver disease by 90%.

- Partial or complete remission occurs in 75% of patients with HCV-associated non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma or lymphoproliferative disease.

- The quality of life of the treated patients improves.

And what does the future hold?

“Hepatitis C has gone from being the most common cause of liver transplants to a curable disease within the last two years,” the speaker enthused. This positive development will continue. In the next few years, drugs can be expected to be approved that are effective for all genotypes. Cure rates will also continue to increase: A recent study using combination therapy of sofosbuvir and velpatasvir showed cure rates up to 100%, and eradications were achieved even in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. It is hoped that drug costs will also decrease so that all HCV patients, regardless of fibrosis stage, can be treated in the future. In addition, simpler therapy standards will develop so that treatment can be provided not only by specialists but also by specialists in general internal medicine.

At the moment, however, there are other challenges with regard to HCV infection, for example the identification of HCV-infected people and the urgent development of prophylactic vaccination – because in most countries people will not be able to afford HCV eradication in the future either.

Source: 55th Continuing Medical Education Davos, January 7-9, 2016

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(2): 30-31