Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP) is a feared risk in epilepsy patients. The new guideline received critical acclaim at the AAN Congress.

Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (“SUDEP”) is a feared, yet under-researched risk in epilepsy patients. SUDEP, as the name implies, occurs without a cause apparent from the circumstances and from an otherwise largely normal state of health. Seizure-associated accidents such as falls and status epilepticus are excluded by definition, but a pathophysiological relationship with seizures is not.

Rare as it may be overall, SUDEP urgently calls for evidence-based information and guidelines that address the issue in a structured manner.

The Americans, more specifically the two societies American Academy of Neurology (AAN) and the American Epilepsy Society (AES), in a joint effort, have now produced a practice guideline to help physicians have an honest and balanced discussion with epilepsy patients on the topic of SUDEP. The publication was presented in abbreviated form in the journal Neurology [1] and was the topic at this year’s AAN Congress in Boston. Two main questions are clarified in the guideline:

- What is the incidence of SUDEP in different epilepsy populations?

- Are there specific risk factors for SUDEP?

In addition, the work was intended to show in which areas there are still gaps in research – as it turned out, there is indeed a great need to catch up.

How often does sudden death occur?

The main findings of the systematic review on which the guideline is based came from twelve Class I studies. They all provided incidence rates, although the authors noted only moderate evidence in the group of children and adolescents with epilepsy and even low evidence in adult patients due to imprecision in the study results. Even when the overall population was considered, the evidence was of limited conviction. Main results are:

- Epileptic children and adolescents 0 to 17 years of age experience SUDEP in 0.22/1000 patient-years (95% CI 0.16-0.31)

- In contrast, adult epileptics are affected more frequently, in 1.2/1000 patient-years (95% CI 0.64-2.32)

- Overall, the SUDEP risk was 0.58/1000 patient-years.

The risk of SUDEP consequently increases with adulthood.

Recommendations: From their results, the societies derived two recommendations, each of recommendation grade B, for the treating physician. On the one hand, when dealing with children with epilepsy or with their parents and caregivers, one should speak of a “rare” SUDEP risk. In addition, it should be pointed out that one child in 4500 children with epilepsy suffers such a sudden death in one year. In other words, annually 4499 out of 4500 epileptic children are spared from SUDEP.

Second, the physician should inform adult epileptics that there is a “small” risk of SUDEP. In any given year, one in 1000 adults with epilepsy is affected by sudden death. In other words, 999 out of 1000 epileptics are spared each year.

The reason for informing patients is that, depending on the culture, but still most epilepsy patients would prefer to be informed about their risk for such a fatal event, the authors said – even if the likelihood is low. However, since patient-specific risk assessment is not yet possible, proactive education carries the risk that the patient may overestimate his or her risk. Without a doubt, this can overly drive fear of such events. According to the guideline, it helps to present risk as the probability of both the occurrence and non-occurrence of the event, to use numbers in addition to words, and to talk about frequencies, not percentages. This can at least partially prevent overestimation.

But what are the risk factors for such a sudden death? And are there any at all, or do they stand up to a clean analysis?

Risk factors – few can convince

The profound heterogeneity of incidence studies cannot be conclusively explained and already suggests that previously undetected and unexplored risk factors may play a role in SUDEP. What do we know today?

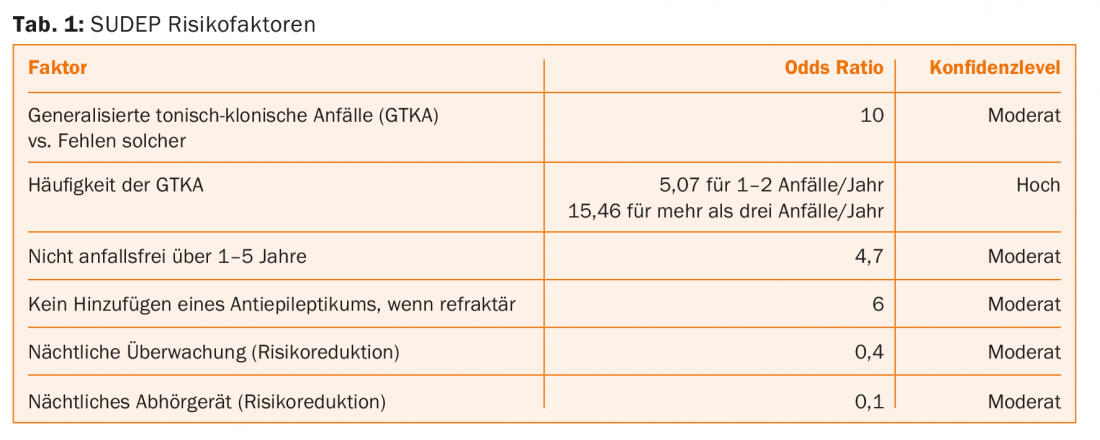

Six Class I and 16 Class II articles provided evidence-based information about this. The results are summarized in Table 1. The presence and especially the frequency of generalized tonic-clonic seizures are shown to be crucial risk factors. Patients with more than three such seizures per year experience a 15-fold increase in risk for SUDEP. Someone who frequently experiences such seizures has an absolute risk of 18 deaths per 1000 patient-years.

It stands to reason that generalized tonic-clonic seizures are not only associated with SUDEP but play a role in its causal course. This in turn suggests that improved control of such seizures – in addition to the many other obvious benefits, e.g. with regard to driving licenses and work – may also reduce the risk of SUDEP. Of course, the disadvantages and burdens of this therapy should not be forgotten, the authors emphasized, but the patient must understand that freedom from seizures here can also make the difference between life and death in individual cases and is therefore of fundamental importance.

Overall, the view that SUDEP is a seizure-associated event with accompanying vegetative symptoms is becoming more firmly established. In the context of an epileptic seizure, pathologic respiratory or cardiac effects could play a role. Various mechanisms are discussed in this context – neurogenic pulmonary edema, seizure-associated myocardial damage, disturbances of cardiac rhythm and respiratory regulation are among them. Autopsy findings demonstrated pulmonary edema and dilated hearts.

Recommendations: With recommendation grade B, clinicians should continue to actively address the latter in epilepsy patients who experience recurrent generalized tonic-clonic seizures and aim to reduce the occurrence (and thus indirectly the risk of SUDEP). This is done while taking into account patient preferences and the individual benefit-risk ratio.

Because nocturnal seizures and postictal respiratory depression/hypoventilation may also be contributing factors, and nighttime “monitoring” or the presence of another person (at least 10 years old) in the bedroom can reduce the risk of SUDEP, it seems reasonable in selected cases to advise patients with recurrent generalized tonic-clonic and also nocturnal seizures and their relatives, if psychologically and physically tolerable, to have a personal nighttime attendant or other measures such as a remote radio or some kind of “baby-phone” (Grade C). However, the authors also clearly point out that this does not directly interfere with the actual pathomechanism of a SUDEP, but merely reduces the risk. Furthermore, there is of course no guarantee that an emerging SUDEP will actually be noticed.

Last, with grade B, the guideline recommends informing the patient that freedom from seizures (especially generalized tonic-clonic seizures) is “strongly associated” with a reduced risk of SUDEP. Uncontrolled epilepsy represents one of the most consistent risk factors in research. Seizure freedom, in turn, is more likely with good medication adherence. The information provided to the patient would thus result in concrete consequences for action: It is easier to advise the patient against the desire to stay longer than necessary with a treatment that is obviously no longer working as intended, and against refraining from further therapeutic progress on the basis of the guideline. Generalized tonic-clonic seizures can be prevented by good adherence, even if (or precisely because) a patient has not previously experienced such severe seizure types (but has experienced focal or myoclonic seizures, for example).

Potential for improvement

The guideline itself notes that SUDEP incidence in different epilepsy populations needs more systematic research. In addition, there is still room for improvement in awareness among experts. To this end, however, it is important to understand in more detail the associations between type, severity, and duration of epilepsy and SUDEP, as well as associations with drug therapy. One approach to help with this is the North American SUDEP Registry (SUDEP Registry). It will add valuable data to research in the coming years.

The fact that the guideline found insufficient evidence for numerous other risk factors, some of which are also mentioned in the current literature, does not mean that these cannot actually be considered as risk factors. The authors emphasize the difficulties of sufficient data collection on the subject, since SUDEP occur firstly rarely, and secondly suddenly and therefore usually outside of medical supervision.

Admittedly, it may be surprising that only the frequency of generalized tonic-clonic seizures could be confirmed as a risk factor with high evidence and that other well-known, frequently discussed factors such as nocturnal seizures, epilepsy duration, age at epilepsy onset, postictal EEG suppression, specific antiepileptic drugs or the number of such, heart rate variability, mental disability, or male sex were of very weak influence in terms of evidence (if at all) and thus did not generate recommendations.

Dangers of an active response

The guidelines assume that talking to the patient about SUDEP is desirable and meaningful. But is this really the case? Doesn’t this rather stir up fear and impose a psychological burden? One guideline staff member pointed out at the congress that her patients already come to her with such thoughts in mind anyway. Those who have witnessed such a violent epileptic seizure in their child, for example, usually report fears of death. Therefore, and because of subsequent improved compliance and seizure control, a proactive response seems reasonable to her. The study situation also points in this direction.

There was news about this at the AAN Congress itself. In a sample of 42 epilepsy patients, SUDEP informational materials were distributed with an opportunity for follow-up questions. Subsequently, the persons filled out a questionnaire. The small U.S. study was part of an AAN presentation. The result was surprisingly clear:

- 100% of patients felt it was their right to know about SUDEP.

- 92% felt that the responsible physician had a duty to inform his patient accordingly.

- 81% reported using this information as an incentive to improve medication adherence.

- However, 30% also confirmed that anxiety had increased as a result (tending to increase in the group with generalized tonic-clonic seizures).

The study authors conclude that the patient’s need for information outweighs his or her fear and that the physician is expected to engage in an appropriate open discussion. One could assume that the positive effects of such information would be greater than the negative effects. Nevertheless, studies show that it is still too seldom discussed with the patient. To facilitate the physician’s approach, written standardized information material that is understandable to the patient, such as that used in this study, could help. It should be mentioned, however, that the participants had all been living with their diagnosis for a long time and had an established doctor-patient relationship.

Source: American Academy of Neurology 2017 Annual Meeting (AAN), April 22-28, 2017, Boston.

Literature:

- Harden C, et al: Practice guideline summary: Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy incidence rates and risk factors. Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. Neurology 2017; 88(17): 1674-1680.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2017; 15(4): 43-45.