The core of the previous classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) originated in 1982 and were only slightly modified in 1997. It is therefore high time to address the issue and incorporate the current state of research as well as new findings. In the long term, several new active ingredients are expected to be approved.

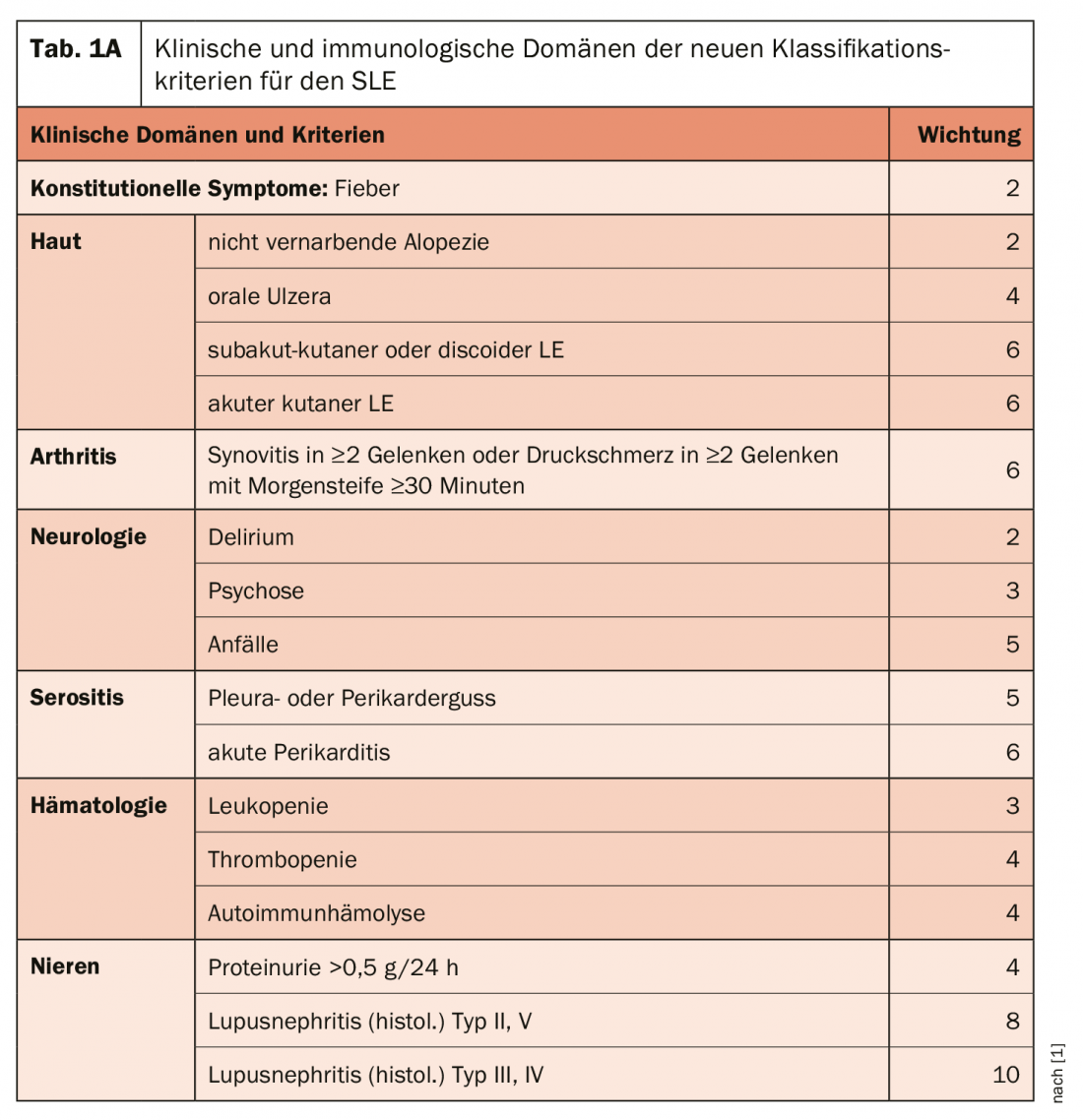

In 2019, new SLE classification criteria were jointly developed and published by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) [1]. A major difference from the old criteria was that the detection of antinuclear antibodies (ANA) is now considered a better entry criterion than a classification criterion due to their high sensitivity but limited specificity. In addition, individual criteria, such as reporting oral mucosal ulcers versus histologically confirmed lupus nephritis, should be weighted differently according to their importance.

New criteria, domains and weightings

“Positive detection of antinuclear antibodies (ANA) on HEp2 cells is required as a prerequisite for the application of the new criteria, although they only need to have been detected once with a titer level of 1:80,” explained Prof. Dr. Christof Specker, Director of the Department of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology, Evangelisches Krankenhaus, Kliniken Essen-Mitte. This titer value is based on a meta-analysis of 64 publications. This showed that for a titer of 1:80, there was a sensitivity of 98% with a specificity of 75%. At 1:160, the specificity was significantly higher at 86%, but the sensitivity was only 96%. In order not to exclude SLE patients if possible, the titer with the higher sensitivity was chosen. “You therefore have to keep in mind that there is practically no SLE without ANA, but with a 75% specificity, one in four of them simply does not have lupus at all,” the expert said. “And nota bene: Over 12% of the normal population have ANA up to 1:320!” The ANA value is therefore an entry criterion, but certainly not sufficient on its own to derive a diagnosis.

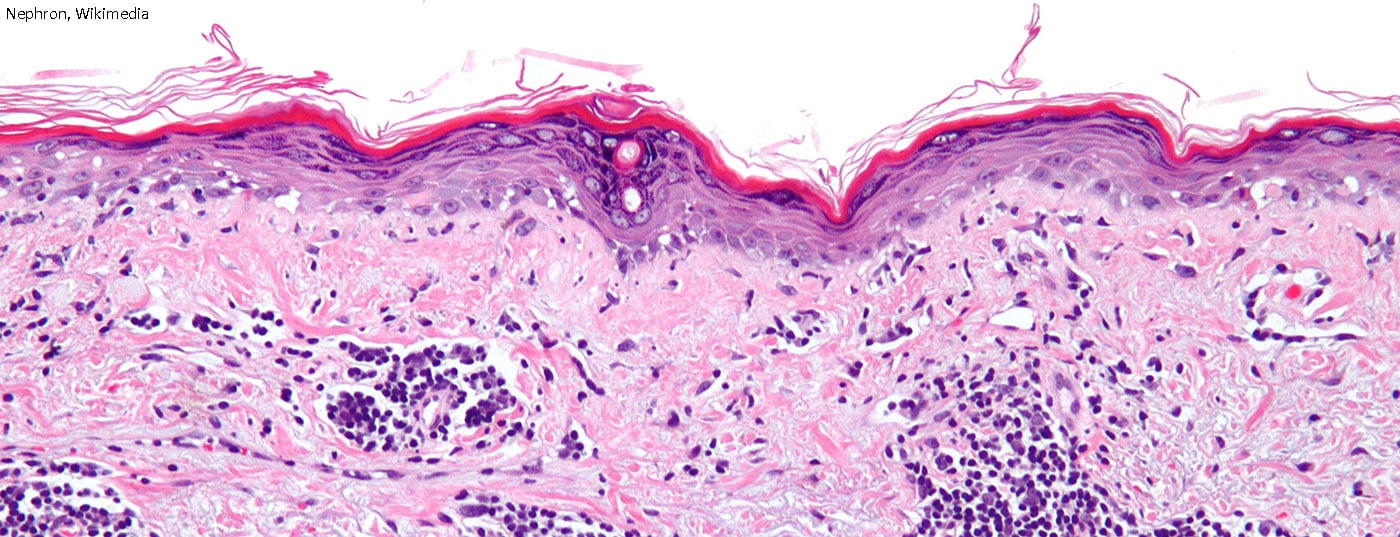

The domain of constitutional symptoms is new: Fever without other cause is listed as a symptom commonly encountered in lupus and is given a weighting of 2 Points (Tab. 1a+b). Within each domain, only the highest value is included in the total score, which allows from 10 points to classify a patient as SLE. “So it’s not like in the past, when you could ‘collect’ points with different criteria within e.g. the skin domain and get to 10 or more.” One of the most important factors is, of course, the renal situation: histological evidence of proliferative lupus nephritis (type III and IV) alone yields 10 points and would thus alone be sufficient (together with ANA detection) to classify lupus. On the immunological domain side – a clinical and an immunological domain are required, but the immunological domain is already given with the ANAs – the highly specific autoantibodies are additionally rated highest. However, in principle, no evaluation should be made if other reasons (infections, medications, other diseases) can also or better explain the symptoms.

The new SLE classification criteria – if used correctly – are likely to be better than the previous ACR and SLICC criteria, according to Prof. Specker. Advantages, he said, are the weighting and better integration of immunological parameters, which should also provide better coverage of early cases. On the other hand, there are disadvantages such as a somewhat higher complexity and the very low limiting titer for the detection of antinuclear antibodies as an entry criterion. The high weighting of arthritis (6 points) is reason to pay special attention that it may not be caused by other causes, the rheumatologist warned.

Management recommendations

In 2019, an update of the EULAR recommendations on the management of SLE has been published [2]. The “overarching principles” that preceded the recommendations include the statement that treatment of organ- or life-threatening SLE consists of an initial phase of high-intensity immunosuppressive therapy to control disease activity, followed by a longer phase of less-intensive therapy to consolidate response and prevent relapses.

Treatment should aim for remission or low disease activity (evidence level 2b/recommendation strength B) and prevention of relapses (2b/B) in all organs, with glucocorticoid dosing as low as possible. SLE relapses can be treated by dose adjustment of current therapies (glucocorticoids, immunomodulators), switching to or adding new therapies, depending on the severity of organ involvement.

The antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) remains the basic therapeutic agent for lupus patients. HCQ is recommended for all patients with SLE (unless contraindicated) at a dose not to exceed 5 mg/kg body weight. Unless there are risk factors for retinal toxicity, an ophthalmologic examination (visual field examination and/or optical coherence tomography) should be performed at baseline, after 5 years, and annually thereafter.

Depending on the type and severity of organ involvement, glucocorticoids (GC) may be used in various doses and routes of administration. Intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy (usually 250-1000 mg per day for 1-3 days) provides immediate therapeutic effect and allows lower initial doses of oral GC. In permanent maintenance therapy, GC should be minimized to less than 7.5 mg/day (prednisone equivalent) and – if possible – discontinued altogether.

Among immunosuppressive therapies, methotrexate has moved to the front because it now has the best evidence. In patients who do not respond to HCQ (alone or in combination with GC) or are unable to reduce GC below a dosage acceptable for long-term therapy, the addition of immunomodulatory/immunosuppressive agents such as methotrexate (1b/B), azathioprine (2b/C), or mycophenolate (2a/B) should be considered. In organ-threatening disease, immunomodulatory/immunosuppressive agents may already be included in the initial therapy. Cyclophosphamide may be used for severe, organ-threatening, or life-threatening SLE.

Among biologics, the only one available so far is belimumab, which can be additionally considered in patients with inadequate response to standard therapy (combinations of HCQ and GC with or without immunosuppressants). If organ-threatening, refractory, or if there are intolerances/contraindications to standard immunosuppressants, rituximab may be considered (off label).

New therapy options

Belimumab is the only targeted therapy for SLE to date. However, there are relatively many substances in clinical development phases. For example, voclosporin (VCS), a new calcineurin inhibitor, is available for the treatment of lupus nephritis. VCS is an immunosuppressant “designed” for use in organ transplantation and autoimmune disease. The analog is reported to have more stable drug levels and is not as nephrotoxic as CSA in its long-term use. In studies, it has been tested in the indications of lupus nephritis, psoriasis and kidney transplantation. In a phase 2 study of 265 patients with active LN (III-IV), VCS vs. placebo was administered twice daily at 23.7 or 39.5 mg, in addition to MMF (2 g/d) and GC. After one year on VCS 23.7, 29.4% of subjects achieved complete renal remission (VCS 39.5: 39.8%), compared with only 23.9% in the placebo arm. This thus argues for an additional effect of CNI in the treatment of LN with MMF, Prof. Specker commented. “So if VCS comes to market, it could get approval, and it would be a good alternative to tacrolimus, which is off label.”

One new substance is obinutuzumab (OBI). As with rituximab, this is also an anti-CD20 antibody. Administration is also similar with 1000 mg twice at 14-day intervals and a repeat after 6 months. OBI is already used relatively widely in hemato-oncology. Again, there was a primary endpoint of complete renal remission in one study. As a result, there was a significant improvement in serology vs. placebo, no increased rate of serious AEs (14.3% vs. 21.0%), and no serious infections (1.6% vs. 12.9%). Infusion-related reactions were naturally more frequent under OBI (15.9% vs. 9.7%). A phase 3 trial is being planned “and I can’t really imagine, given the results so far, that this won’t work,” Prof. Specker was confident.

Interferon-α (IFNα) has long been considered a promising target for SLE therapy. Anifrolumab (ANFR) is a monoclonal antibody that is not directly directed against IFNα but against its receptor (IFNAR1), which antagonizes not only the effects of IFNα but also those of other interferons. With TULIP-1 and TULIP-2, there were two phase 3 studies on the effect of ANFR in SLE – with almost opposite results. There was little difference between the two studies: the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the study design, and even the group sizes were virtually identical. However, the primary endpoint of an SRI-4 response, initially defined the same as in TULIP-1, was then changed in TULIP-2 before unblinding and after consultation with the FDA to the so-called BICLA response at week 52 with stable SOC.

The TULIP-1 trial joined the ranks of unsuccessful SLE trials and was thus eigtlich disappointing. In TULIP-2, however, anifrolumab was superior to placebo in nearly all endpoints, including disease activity, skin involvement, and GC requirement. There were no new safety signals in either study. The tendency to favor herpes zoster infections was already known for anti-IFNα therapies and was also confirmed for ANFR in both studies. The successful TULIP-2 trial – with an “accelerated approval process” already promised by the FDA – will very likely lead to the approval of this new therapeutic principle for SLE, Prof. Specker predicted. However, it remains unclear how the striking differences in the results of these two almost identical studies could have occurred. According to the expert, a subsequent change of the primary endpoint would not have been necessary at all; the SRI-4 response index was also achieved in TULIP-2, and if one compares the studies with regard to the difference between the placebo response and the SRI-4 response, one arrives at differences of more than 22 percentage points (Tab. 2). “Don’t ask me how to explain it, I don’t know either,” the expert expressed his perplexity.

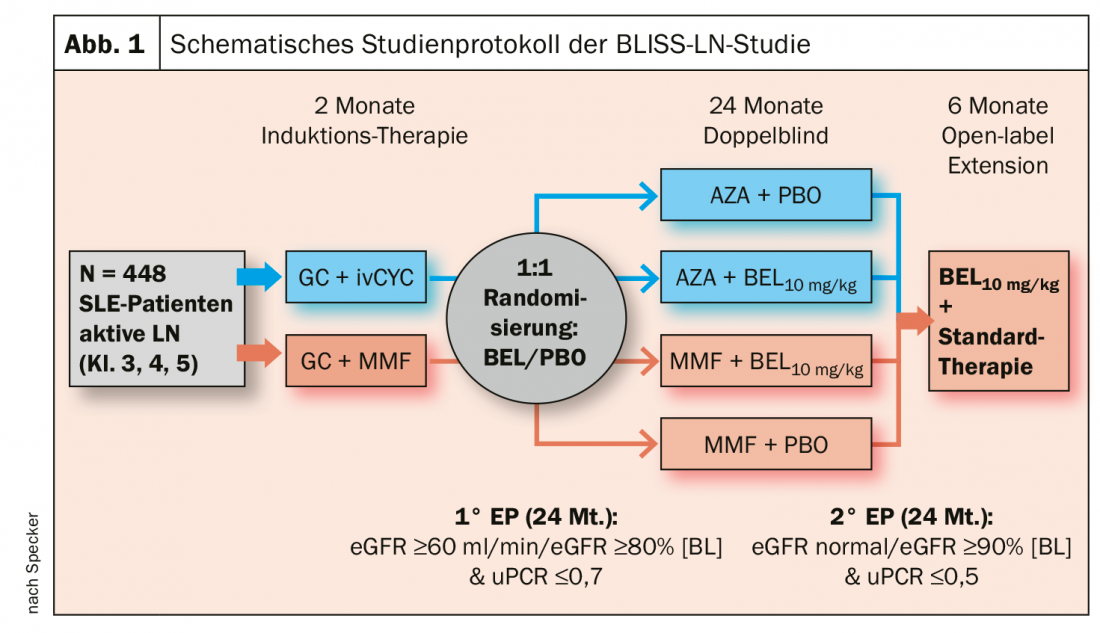

Belimumab with benefits in LN

There is also news on the use of belimumab for remission maintenance in lupus nephritis (LN). Until now, it has always been said that belimumab is useless in nephritis, “and in induction therapy, it is,” Prof. Specker explained. But in the phase 3 BLISS-LN trial, 448 SLE patients with active lupus nephritis were initially treated conventionally with either high-dose glucocorticoids + i.v. cyclophosphamide (CYC) or glucocorticoids + mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) and placed into remission. After this two-month induction therapy, patients were randomized 1 to 1: Those previously receiving CYC were now treated with azathioprine (AZA). Those who previously received MMF continued to receive it. For the 24-month period, patients in maintenance therapy in both arms were also divided into one group each receiving additional belimumab (10 mg/kg/month) or placebo as infusion.

The primary endpoint was defined as eGFR ≥60 ml/min/1.73m2 or no decrease in eGFR from pre-LN baseline of more than 20%, a urine protein creatinine ratio (uPCR) of ≤0.7, and no treatment failure or relapse. The strictest secondary endpoint of complete reneal remission (CRR) was defined as eGFR in the normal range or no more than 10% below baseline and a uPCR <0.5.

The primary endpoint was met at week 104 by 43% on BEL + standard of care (SOC), compared with 32% on placebo. The 11% increase was statistically significant (OR 1.44; 95% CI 1.04-2.32; p=0.03) (Fig. 1). There was also a statistically significant benefit for belimumab over placebo in the key secondary endpoints, the expert said. His conclusion: the additional administration of BEL in the maintenance therapy of lupus nephritis reduces the risk of recurrence. Prof. Specker therefore also expects approval for belimumab as an add-on therapy for such treatment cases in the medium term. According to him, the only question that might remain open is whether this will also apply to s.c. therapy, which is now available and easier to handle.

Source: Rheuma Update Wiesbaden (D)

Literature:

- Aringer M, et al: Ann Rheum Dis 2019; 78(9): 1151-1159.

- Fanouriakis A, et al: Ann Rheum Dis 2019; 78(6): 736-745.

InFo PAIN & GERIATry