Three complexities converge in the diabetologic therapy of the elderly: the therapy of a chronic disease, the therapy of diabetes mellitus per se, and geriatric health care. This often makes optimized and safe diabetes therapy in old age a real challenge. Stepwise clarification of three basic questions can facilitate diabetologic treatment planning in older age: 1. is insulin therapy necessary? 2. what is the goal of diabetes therapy? 3. to what extent is the necessary therapy feasible? The key to optimized therapy is individualization of the treatment plan with realistic consideration of all psychosocial circumstances and age-specific comorbidities. Without inclusion of all those involved in therapy and care, realistic therapy planning and implementation is difficult. An optimized therapy plan needs patience, experience and continuous adjustment.

In affluent industrialized nations, one in five people over the age of 75 is diagnosed with diabetes mellitus; in nursing homes, one in four [1]. The prevalence will continue to increase over the next decades. Therefore, those who are responsible for the medical care of the elderly should be familiar with the management of diabetes mellitus in older age.

Optimization of therapy

The definition of “optimal” diabetes treatment becomes broader and more ambiguous with age. Thus, the utility of standardized guidelines is declining and individualized treatment plans are coming to the fore.

It is not uncommon for diabetes-specific therapy to be simple at an older age and should not then be unnecessarily complicated. In many cases, however, the therapy can only be optimized with enormous effort, which is not always justified. Finding the right balance here is a challenge.

For diabetes mellitus-specific, individualized therapy planning, a three-step approach is recommended: Assessing the exogenous insulin requirement, determining the therapy goal, and creating a realistic therapy plan.

Estimation of exogenous insulin requirement.

Since the need for insulin therapy dictates further planning, it must first be determined whether endogenous insulin production has dried up to the point that metabolic derailment is imminent. Type 2 diabetes mellitus can be viewed as a spectrum of different stages of exogenous insulin dependence. If the diabetes can be optimized by dietary measures or metformin alone, endogenous insulin production is so well preserved that exogenous substitution will usually no longer be necessary in the remaining lifetime. With suboptimal diabetes control, despite multiple oral medications, endogenous insulin production is likely to cease before the end of life.

Initiate insulin therapy: if insulin therapy is deemed necessary, then immediate discontinuation of all oral antidiabetic agents, including metformin, should be considered in the elderly. This is often seen as a relief by the patient and all caregivers. For elderly patients, small therapy adjustments can become very important, such as insulin pens that require reduced thumb pressure for insulin delivery or blood glucose meters with a particularly visible blood glucose display. Therefore, help from healthcare professionals experienced with this should be sought when initiating insulin therapy.

Insulin regimens should be detailed because elderly patients and changing caregivers rely on the most accurate instructions. Creating detailed and individualized insulin regimens is time-consuming and requires regular adjustments. For useful recommendations in insulin therapy for dependent patients, reference may be made to a recommendation of the Swiss Society of Endocrinology and Diabetology (SGED) [2].

Differential diagnosis LADA: At this point “Late onset autoimmune diabetes of the adult” (LADA), so to speak the “type 1 diabetes of the adult”, should be mentioned. LADA is unfortunately often not considered as a differential diagnosis, although its prevalence in the elderly is around 5% [3]. Autoimmune destruction of beta cells is slower in older age, so that osmotic symptoms and/or ketosis are often not present at diagnosis and therefore clinical differentiation between LADA and type 2 diabetes mellitus is not possible. In the early stages, LADA can be treated with oral antidiabetic agents, but the time of need for exogenous insulin should not be missed. Therefore, closer follow-up is necessary.

Determination of the therapy goal

Once the need for insulin therapy has been clarified, the therapy goal must be formulated as precisely as possible. As more and more factors influence the therapy with increasing age, the therapy objectives must also be more and more individualized. Guidelines often do not help here either. The wishes of non-dementia patients should be respected and incorporated into treatment planning, even if they are extravagant.

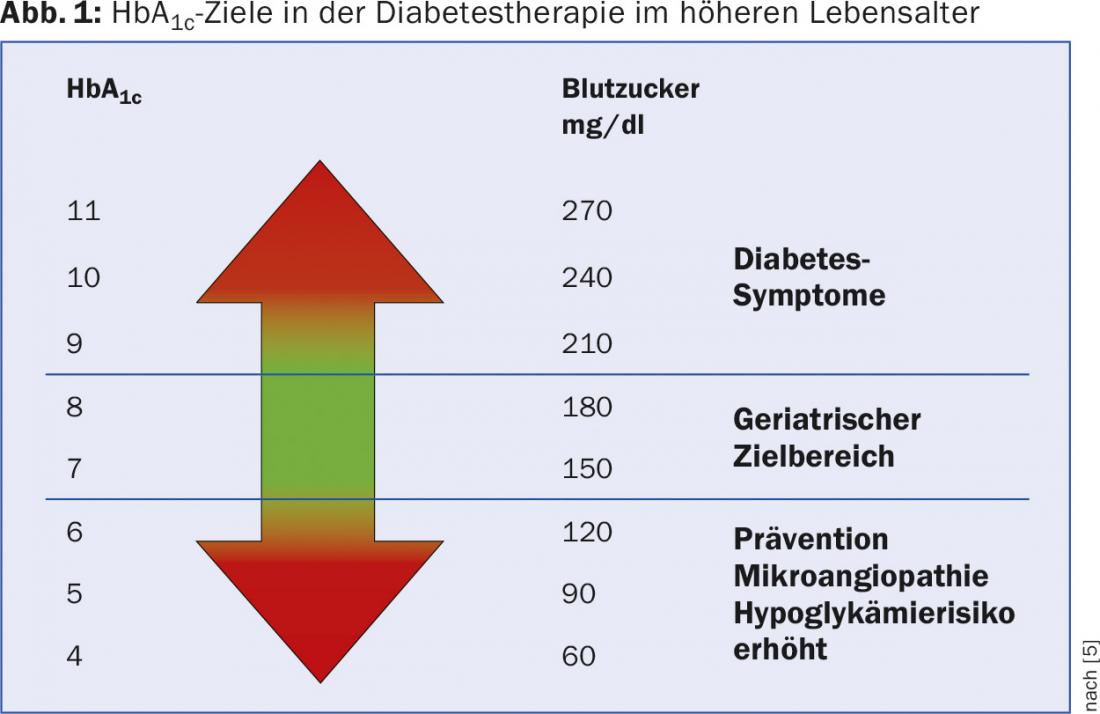

The achievement of physiological HbA1c target values is increasingly relegated to the background as a therapeutic goal, since this only serves to reduce the risk of vascular complications, which, however, becomes increasingly irrelevant with increasing age. The HbA1c target value should not be made dependent on a defined, chronological age. A biologically young 80-year-old patient with long-lived relatives as an example may well benefit from vascular complication reduction.

Individualized approach: At the end of life, the primary therapeutic goal is the avoidance of osmotic symptoms [4], which occur only when the renal glucose reabsorption threshold is exceeded generally from a glucose level of 10 mmol/l,. However, at what glucose level a patient then finds polyuria and thirst bothersome is extremely variable from patient to patient. Again, an individualized approach is recommended, and blood glucose or HbA1c targets should initially be set too high rather than too low. At an HbA1c level of 9% (glucose levels of 13-14 mmol/l), clinically relevant symptoms rarely occur. Even HbA1c values above 10% (glucose values of 15-16 mmol/l) often do not cause complaints that limit the quality of life.

Authentic social history: the hypoglycemic problem must not be underestimated in older age, otherwise the consequences are far-reaching, sometimes fatal. Physiological warning mechanisms become more ineffective with age, so that even severe hypoglycemia is not recognized by the patient and the social environment. The error rate in self-treatment also increases. In the case of neuroglycopenic events, the associated risk of harm is greatly increased due to age-associated physiological changes (e.g., general frailty) and psychosocial events (e.g., isolation, dementia). It is not uncommon for there to be a reluctance to accept assistance or a target reduction when it comes up for discussion. A realistic assessment of the risk of hypoglycemia is only possible if one knows the patient and the social circumstances well, or at least can obtain an authentic social history. The German Diabetes Society (DDG) recommends a “geriatric target range” for the HbA1c target, which represents a compromise between the risks associated with low and high HbA1c levels (Fig. 1) [5].

Creating a realistic target plan

For realistic therapy implementation, the attending physician must be as familiar with the patient’s abilities and limitations as with their living situation. Therefore, the preparation of a diabetologic therapy plan during acute, inpatient admissions is questionable and should be performed in a phase of extensive normality and stability in an outpatient setting close to the patient’s home.

If there is any doubt about the patient’s self-assessment, all those involved in the care must be included in the treatment planning. The following factors must then be elicited in joint discussion:

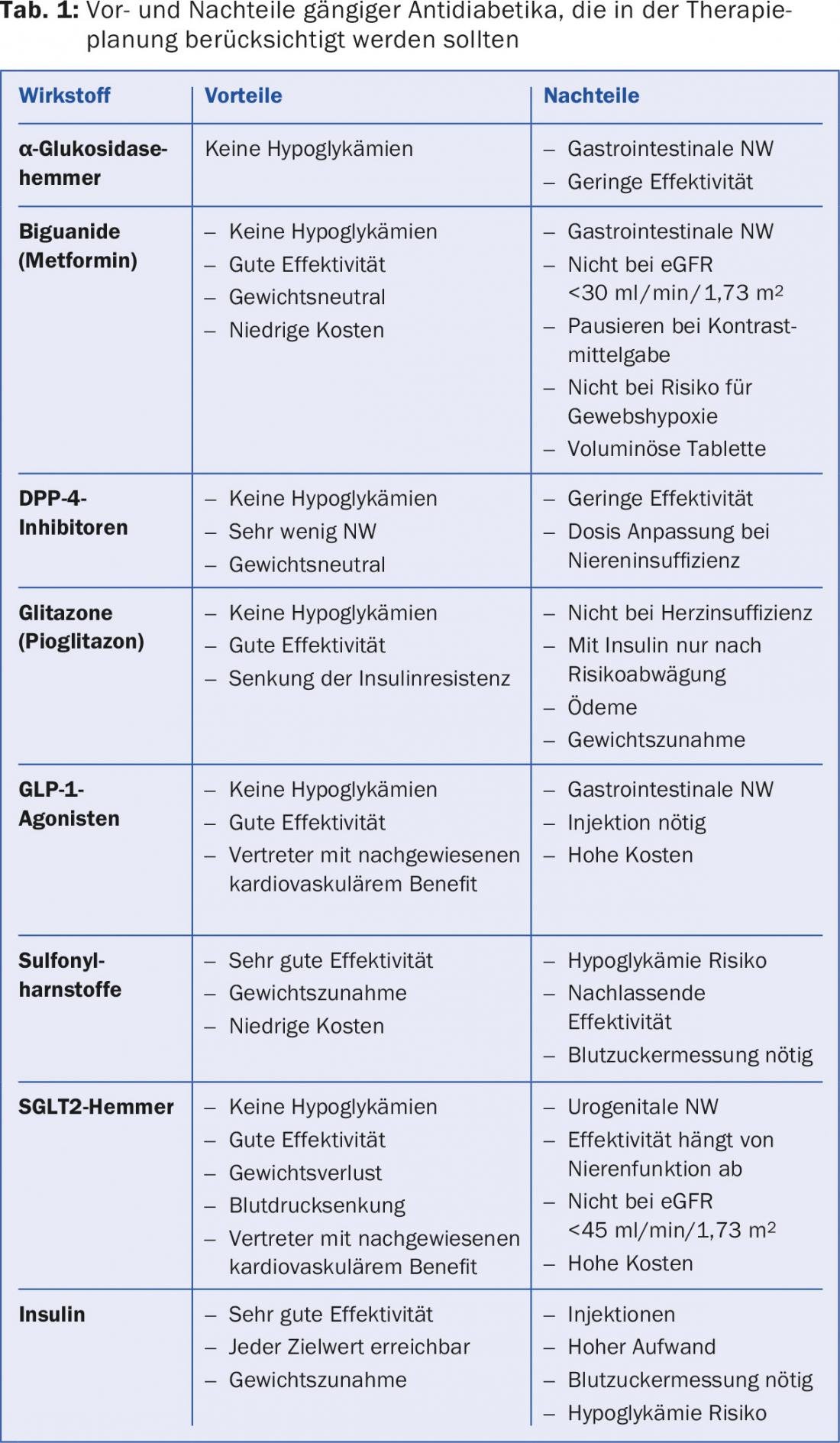

Isolation and immobility: isolation greatly increases the risks associated with hypoglycemia, as discussed above. The supply of utensils necessary for blood glucose measurement and insulin injection as well as anti-diabetic medications must be ensured. With an ever-increasing variety of therapies and materials, this is no easy task (Tab. 1).

Dependence on family and/or caregivers: Once a dependence exists, treatment planning becomes many times more complex and usually limited. This aspect is often neglected and then leads to frustration and malcompliance. For patients in nursing homes with changing nursing staff, instructions must be extremely detailed. This is only possible with individualized therapy regimens, the creation of which is time-consuming and must be discussed with the nursing staff.

Limitations of cognition and functionality: The declining intellectual capacity of elderly patients makes therapy optimization a challenge. Neurocognitive impairments often develop gradually and are initially overlooked. The self-assessment of the treated patients regarding the preserved abilities is usually unrealistic. Progression of neurocognitive impairment requires regular adjustment of the treatment plan.

Failure of organ function: If renal function is impaired, insulin doses must be reduced, and many oral anti-diabetic drugs must be stopped or adjusted according to the glomerular filtration rate. With declining eyesight, blood glucose meters with larger and illuminated displays should be used. For a summary of other age-related comorbidities that influence diabetes therapy, the aforementioned DDG guideline can be consulted [5].

Literature:

- Tamayo T, et al: Dtsch Arztebl Int 2016; 113(11): 177-82; DOI: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0177.

- Felix B, et al: Swiss Medical Forum 2016;16(2): 45-47.

- Turner R et al: Diabetes Study Group. In: Lancet. 1997; 350(9087), S. 1288-1293

- American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2016;39(Suppl. 1): PP. 81-S85

- Zeyfang A, et al: Diabetes mellitus in old age. Diabetology 2016; 11 (Suppl 2): pp. 170-S176.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(2): 13-15