With increasing hours of sunshine, outdoor sporting activities are also on the rise again. This is also accompanied by an increase in injuries and the subsequent desire for a painkiller. How common the use of over-the-counter painkillers is in amateur and professional sports and what side effects this can bring is explained in this review article.

The sunshine hours are increasing, the temperature is rising, spring is finally here! Now, in the morning or evening before/after work, sports can be done again, be it running, on the bike or swimming in the lake. Folk races and other sporting events follow one after the other. Unfortunately, during this period, consultations due to injuries also increase, in the majority due to overuse. Often a painkiller is then asked for so that participation in the next competition is still possible. For top athletes, the use is sometimes considered necessary (important competition, selection, etc.). But what about amateur athletes?

The use of painkillers in popular sports

The Jungfrau Marathon was the site of one of the first studies to draw attention to the possible misuse of pain medication. NSAIDs were detected in the urine sample of 34.6% of the participating athletes. Comparable numbers were found at the following events:

- El Andalus ultramarathon: 47% of participants took painkillers, 60% of them NSAIDs [1].

- Bonn Marathon 2009: 61% painkillers [2]

- Berlin Marathon 2010: 49% painkillers [3]

According to reports, in Berlin, 11% of participants already competed with pain and 15% of runners were taking multiple NSAID agents [2]. Significantly more gastric cramps and cardiovascular events such as arrhythmias and palpitations were found in athletes taking NSAIDs [3]. The following serious adverse events occurred only in athletes who had taken NSAIDs [3]:

- Three participants with oliguria/anuria after ibuprofen 1× 600 mg and 2× 400 mg, respectively.

- Four participants with gastric bleeding on acetylsalicylic acid 500-1000 mg

- Two participants with myocardial infarction treated with acetylsalicylic acid 100 mg, resp. 500 mg

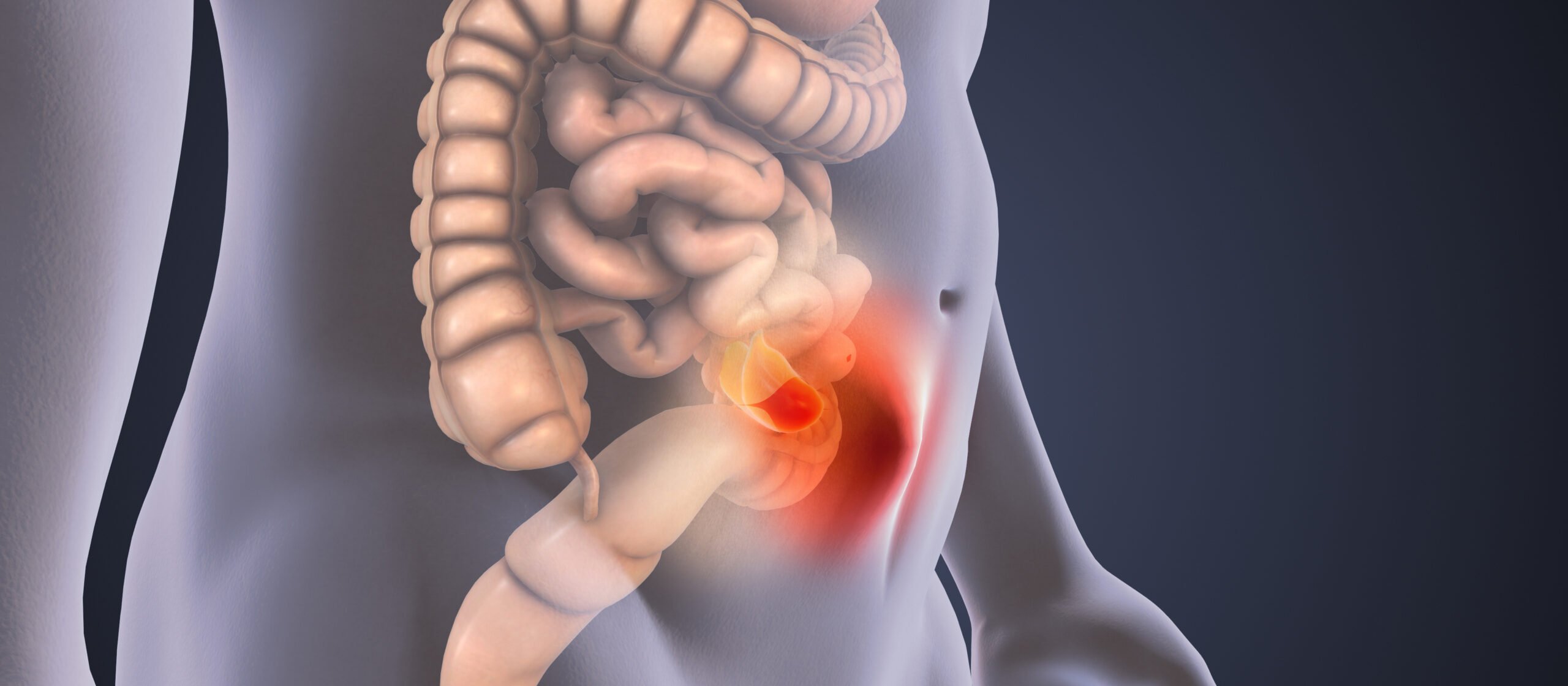

There are several studies on systemic side effects of NSAIDs in athletes. Alaranta et al. [4] have reported an incidence of dyspepsia of 20%. Increased intestinal wall permeability with malabsorption and, in severe cases, gastrointestinal hemorrhage caused by local ischemia have been described [5].

Furthermore, exercise-induced hyponatremia in endurance sports, exacerbated by NSAID use, is controversially discussed in the literature [6]. An association between NSAIDs and sudden cardiac arrest in sports is debated, although studies are lacking. However, it has been shown that even taking them for seven days increases the risk of recurrent myocardial infarction, even in young patients [7]. Whether this is also true for the initial event, especially in heart-healthy athletes, is unclear.

Although studies have shown similar efficacy of topical treatment for many musculoskeletal conditions [8], NSAIDs are most commonly taken in oral form [9].

What is frightening is the fact that many amateur athletes are not aware of the danger of taking NSAIDs. In a 160 km ultramarathon, one-third of participants knew nothing about the dangers of taking pain medications [1]. Even as a general and sports physician, one is rarely asked by amateur athletes regarding side effects, as some studies show [1,2,3,10]. Also staggering is the fact that, depending on the study, up to 50% of junior athletes are already taking NSAIDs on a regular basis [10].

The use of painkillers in elite sports

Corrigan and Kazlauskas conducted the first major study of drug use in elite sport during the 2000 Sydney Olympics [11]. During the doping controls in Sydney, the athletes were asked about their drug intake during the previous 72 hours and a corresponding analysis was also carried out. The result: 25.6% of the athletes took NSAIDs, in some cases even several agents simultaneously. Many wondered why the best and supposedly “healthy” athletes take so many painkillers.

High levels of drug abuse were also demonstrated at FIFA World Cups in all age categories from 2002 to 2007 [9,12]. Pain medications were detected the most. 30% of all adults and 20% of all 17- and 20-year-olds took NSAIDs before each game. Although FIFA launched an awareness campaign prior to the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, the number of medications indicated, especially NSAIDs, remained high in subsequent World Cups until 2014 [13,14]. Interesting are the results of an unpublished, pubmed-based analysis [15] of all published data up to 2010, which examined medication use a few days before a sporting event. The following factors were shown to influence medication use:

- Sports doctor

- Geographical origin

- (also associated with sports doctor)

- Age of the athlete

- Sport

- Gender

For example, NSAIDs were systematically administered to all players on a team before each match in a tournament [14].

No correlation was found between reported injuries in FIFA World Cup matches and painkiller use, nor with team success, or whether the team athlete was in the starting lineup or a substitute in the match or not on the match sheet at all [12,16].

NSAIDs and their effect on the musculoskeletal system

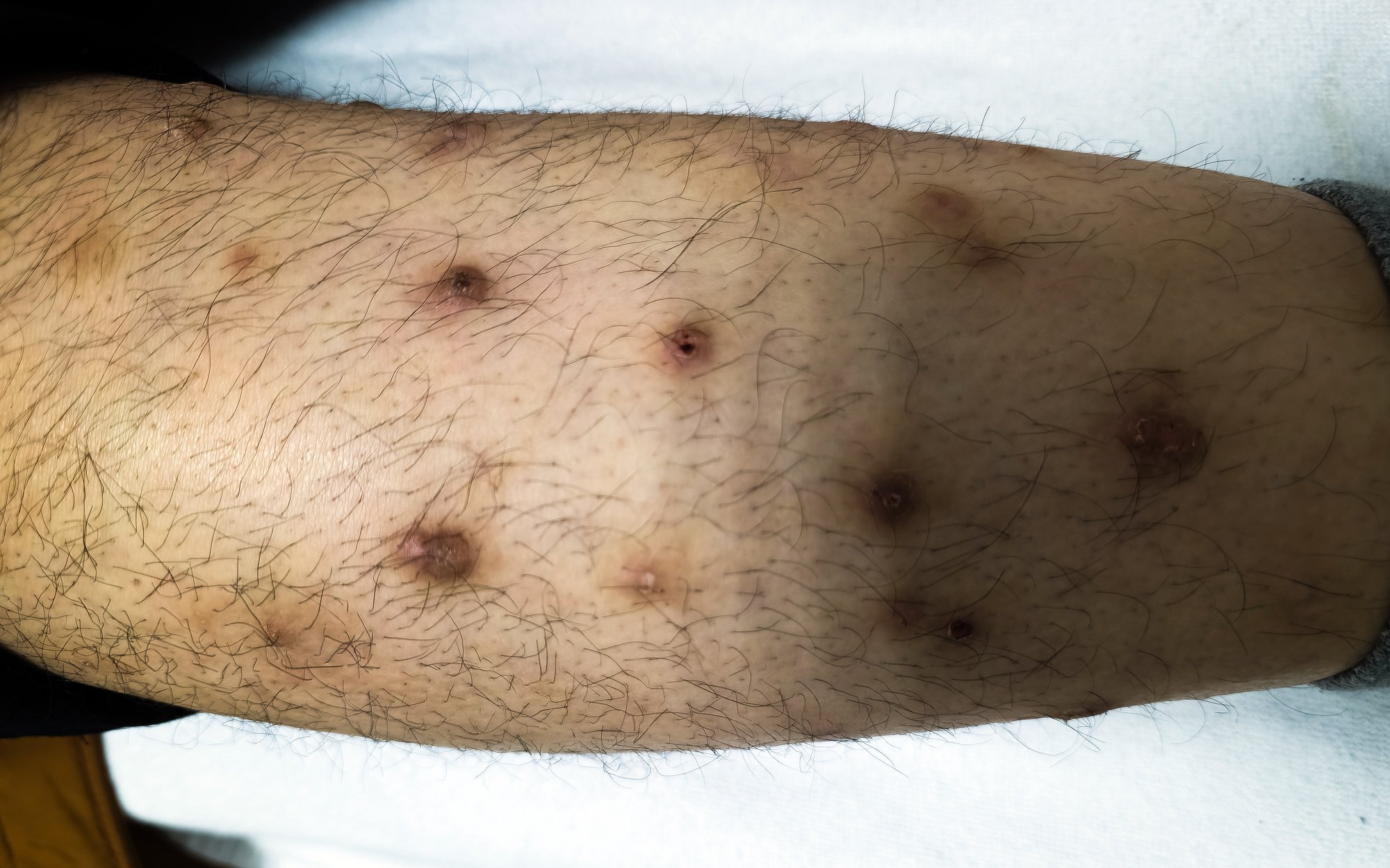

Muscle tissue: After muscle injury, healing proceeds in three stages: inflammation, proliferation and remodeling. Initially, additional cell damage occurs during the inflammatory phase for 3-5 days due to cell migration of neutrophil granulocytes. Thereafter, the healing process is driven by macrophages through the production of cytokines, growth factors and oxygen radicals. This mobilizes satellite cells and stimulates them to proliferate. They then merge with the myocents. Taking NSAIDs can affect each of these steps [17]. If NSAID use during the first 48-72 hours after a structural muscle lesion has some benefits in reducing cellular-induced damage, its use after the early inflammatory phase results in poorer quality tissue healing. NSAID use for muscle soreness relieves pain and may allow early return to sport, but diminishes adaptive training processes in the muscle, and thus is not indicated [18].

Bone tissue: The bone remodeling processes, which are stimulated both in response to mechanical stimulus and during fracture, are controlled in particular by the COX-2 enzyme. Thus, selective COX-2 inhibitors should be used with particular caution. This relationship has been demonstrated in both animals and humans [19].

Especially after hip surgery, indomethacin, another NSAID, is used to prevent bone formation in the tissue (heterotopic ossification). One study compared the efficacy of indomethacin with local irradiation. Both therapies worked equally well with respect to heterotopic ossification. However, something stood out about the study participants who had broken long bones in addition to their hips. Of these patients, 27% of those on indomethacin therapy developed a bone healing disorder. Among patients who did not receive indomethacin, it was only 7% [20]. Ultimately, it stands to reason that NSAIDs may also impair bone healing if they are already being used for heterotopic ossification prophylaxis.

Tendon tissue

Various remodeling and reparative cascades occur during a tendon injury. The inflammatory phase lasts 6 to 10 days. After the initial trauma has triggered a hematoma, remodeling and formation of granulation tissue occurs. Epitenon and endotenes form the basis for migrating cells: Phagocytes and myofibrocytes. At this stage, the healing tissue does not yet have any mechanical properties. The remodeling processes can be slowed down with NSAIDs during this phase, and the fibrous callus becomes softer. In the rat model, this can result in the loss of up to one-third of the biomechanical traction force [21]. However, in acute tendinopathy or peritenonitis, NSAIDs are indicated and effective [21].

Tapes

Taking into account 23 clinically controlled and randomized trials, Bleakley et al. summarized in their systematic review that, for example, the use of NSAIDs in the early phase of ankle injuries for analgesia has significant positive effects on joint functionality. At the same time, however, they warn against the side effect of possibly loading an ankle joint that was free of pain at an early stage too early, i.e., of cutting off “warning signs” through excessive analgesia [22]. For example, poorer mobility, more swelling, and higher-grade instability were observed in a collective of Army members two weeks after injury and NSAID use at baseline [23].

Summary

NSAIDs are potent drugs with a rapid and effective analgesic effect. However, their anti-inflammatory property means that regular use reduces training adaptation processes and thus performance development, qualitatively weakens tissue healing, and can even lead endurance athletes (although rarely) into acute health problems.

In the competition phase, the use of NSAIDs can certainly not be dispensed with in cases of excessive inflammation. In the preparatory phase, pain should be perceived as a warning signal, an adequate inflammatory situation should be tolerated in terms of adaptation processes, and, if necessary, pure pain medication or alternative treatment methods should be used selectively and with caution.

Take-Home Messages

- The use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may cause gastrointestinal, cardiac, or nephrologic side effects.

- NSAIDs have a negative effect on fracture healing and negatively affect muscle and ligament repair processes when taken for prolonged periods (more than 2-3 days).

- NSAIDs are not only analgesics, but their predominantly anti-inflammatory effects can negatively influence healing and adaptation processes.

- Pain should be interpreted as warning symptoms. Therefore, the cause should be addressed primarily (load adaptation or other factors) and alternative medications should be used if necessary (bromelain, arnica, comfrey).

- In the case of an excessive inflammatory reaction, the use of NSAIDs is also justified in sports.

- There is inflammation without healing, but no healing without inflammation.

Literature:

- Scheer BV, Murray A: Al Andalus Ultra Trail: an observation of medical interventions during a 219-km, 5-day ultramarathon stage race. Clin J Sport Med 2011; 21(5): 444-446.

- Brune K, et al: [Drug use in participants of the Bonn Marthon 2009]. MMW Fortschr Med 2009; 151(40): 39-41.

- Küster M, et al: Consumption of analgesics before a marathon and the incidence of cardiovascular, gastrointestinal and renal problems: a cohort study. BMJ Open 2013; 3: e002090.

- Alaranta A, et al: Ample use of physician-prescribed medications in Finnish elite athletes. Int J Sports Med 2006; 27(11): 919-925.

- Van Wijck K, et al: Aggravation of exercise-induced intestinal injury by ibuprofen in athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2012; 44(12): 2257-2262.

- Hoffmann MD, et al: Characteristics of 161-km ultramarathon finishers developing exercise-associated hyponatremia. Res Sports Med 2013; 21(2): 164-175.

- Schjerning Olsen AM, et al: Duration of treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and impact on risk of death and recurrent myocardial infarction in patients with prior myocardial infarction: a nationwide cohort study. Circulation 2011; 123(20): 2226-2235.

- Mason L, et al: Topical NSAIDs for chronic musculoskeletal pain: systematic review and meta- analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2004; 5: 28.

- Tscholl P, et al: The use and abuse of painkillers in international soccer: data from 6 FIFA tournaments for female and youth players. Am J Sports Med 2009; 37(2): 260-265.

- Holmes N, et al: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in collegiate football players. Clin J Sport Med 2013; 23(4): 283-286.

- Corrigan B, Kazlauskas R: Medication use in athletes selected for doping control at the Sydney Olympics. Clin J Sport Med 2000; 1002(13): 33-40.

- Tscholl P, Junge A, Dvorak J: The use of medication and nutritional supplements during FIFA World Cups 2002 and 2006. Br J Sports Med 2008; 42(9): 725-730.

- Tscholl PM, Dvorak J: Abuse of medication during international football competition in 2010 – lesson not learned. Br J Sports Med 2012; 46(16): 1140-1141.

- Tscholl PM, et al: High prevalence of medication use in professional football tournaments including the World Cups between 2002 and 2014: a narrative review with a focus on NSAIDs. Br J Sports Med 2015; 49(9): 580-582.

- Tscholl PM, et al: Risk factors for the use of medication in elite athletes. Paper presented at: ECSS, 2009; Oslo.

- Tscholl P, et al: The use of drugs and nutritional supplements in top-level track and field athletes. Am J Sports Med 2010; 38(1): 133-140.

- Mackey AL: Does an NSAID a Day Keep Satellite Cells at Bay? J Appl Physiol (1985) 2013; 115(6): 900-908.

- Tscholl PM, Gard S, Schindler M: A sensitive approach to the use of NSAIDs in sports medicine. Swiss Sports & Exercise Medicine 2016; 65(2): 15-20.

- Simon AM, O’Connor JP: Dose and time-dependent effects of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition on fracture-healing. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007; 89(3): 500-511.

- Giannoudis PV, et al: Nonunion of the femoral diaphysis. The influence of reaming and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2000; 82(5): 655-658.

- Leumann A, Iselin L: Tendons – morphology, biology and biomechanics. Swiss Journal of Sports Medicine and Sports Traumatology 2015; 63(4): 6-10.

- Bleakley CM, McDonough SM, MacAuley DC: Some conservative strategies are effective when added to controlled mobilization with external support after acute ankle sprain: a systematic review. Aust J Physio 2008; 54: 7-20.

- Slatyer MA, Hensley MJ, Lopert R: A randomized controlled trial of piroxicam in the management of acute ankle sprain in Australian Regular Army recruits. The Kapooka Ankle Sprain Study. Am J Sports Med 1997; 25(4): 544-553.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(6): 33-36