An increasing number of studies confirm that the inclusion of palliative care (PC) in the care of people with heart failure alleviates their symptoms, improves quality of life and reduces the number of hospitalization days. Today, PC should also be used in heart failure based on need rather than prognosis. Many HI patients suffer from pain; reasonable opiate-based pain management is useful. Respiratory distress is often noticed but too rarely treated. The decision-making process regarding possible restriction of ICD activity at the end of life is complex and often subject to dynamics. In cases of refractory HI and foreseeable end of life, a palliative consultation may be helpful to enable a symptom-focused therapy and to prevent repeated hospitalizations (“revolving door effect”).

The treatment guidelines of both the European and American cardiac societies recommend the introduction of palliative care (PC) in patients with advanced heart failure (HI). An increasing number of studies confirm that the inclusion of PC in the care of people with HI alleviates their symptoms, improves quality of life, and reduces the number of hospitalization days [1]. The practical implementation of the guidelines in everyday practice is unsatisfactory worldwide. This article describes the concept of modern PC and the possible applications of its principles in patients with HI.

Heart failure from the palliative point of view

Modern drug and device therapies (biventricular pacemakers, defibrillators, etc.) have significantly improved the survival of patients with heart failure over the past 20 years. Nevertheless, heart failure remains a very burdensome, chronically progressive disease with mortality comparable to cancer. Heart failure can develop as a result of virtually any heart disease. Damage to the heart initiates a remodeling process (remodeling) that helps preserve cardiac function but has an adverse effect on cardiac function over time, further promoting heart failure.

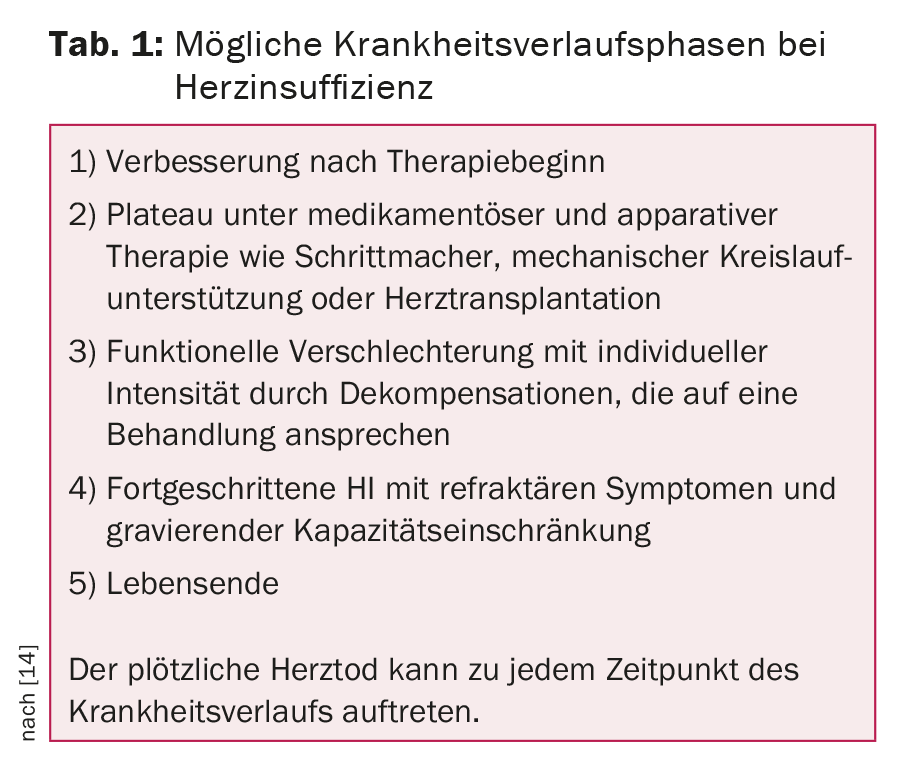

Many patients suffer from severe shortness of breath at the slightest exertion. In addition, there is often a pronounced fatigue and intolerance of performance, which leads to a significantly reduced quality of life. There is a typical pattern of disease progression (Table 1).

After starting treatment, the functional capacity improves in the majority of patients and symptoms subside. However, after varying lengths of time, the heart dysfunction and symptoms increase again. HI causes death in some patients, symptoms and impairment in others, but death will occur as a result of another disease (secondary disease) or occasionally an accident. The risk of sudden cardiac death accompanies people with HI even in less advanced stages of the disease. In patients dying because of or with heart failure (as a secondary condition), implanted electronic devices (e.g., cardioverter defibrillators, ICDs) can significantly affect the quality of dying if they remain fully active.

From a palliative perspective, HI is an incurable and progressive disease associated with high symptom burden and risk of earlier death despite the best treatment.

Modern Palliative Care

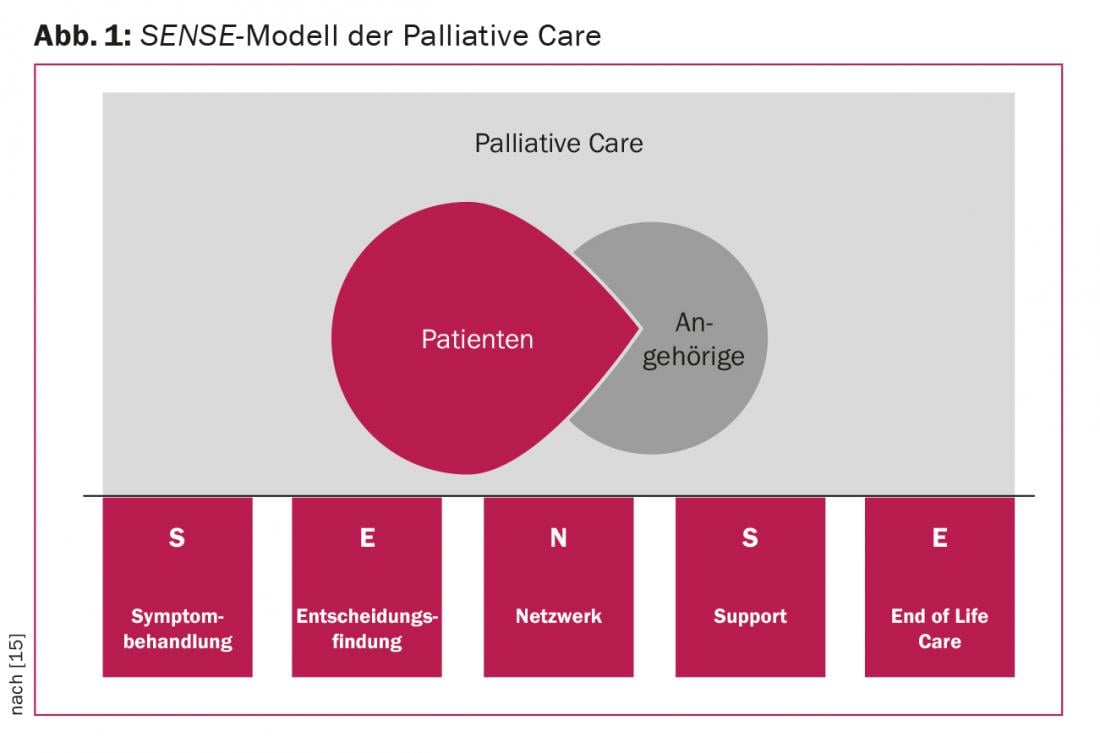

Today, palliative care is defined as the care and treatment of people with incurable, life-threatening and/or chronically progressive diseases, with the goal of making the remaining life as good and active as possible. PC is not limited to oncologic disease nor to clearly reduced survival. Within the framework of PC, one takes care of improving the quality of life and preventing the suffering of patients and their relatives in physical, psychosocial and spiritual dimensions. That is why PC is provided by a multi-professional team. According to the basic principles of PC, death (when unavoidable) is considered a natural end of life and is neither delayed nor hastened. In a modern model, PC is no longer to be used after curative treatment has been completed, but is built up in parallel with it as a supplement according to existing needs. In such a perception, PC gives additional support to sufferers and their relatives, not only at the end of life, but throughout the course of the disease. The elements of the PC can be described by the English acronym SENSE (Fig. 1).

Implementation of palliative care in heart failure patients.

Based on disease progression curves (disease trajectories), attempts were made in the past to define the switch from a curative to a palliative treatment approach with prognostic criteria (high risk of death within 6-12 months) in HI patients – similar to cancer patients. However, this transition point concept is not practical, because due to the unpredictable trajectory of HI, the present algorithms cannot determine the mortality risk with satisfactory accuracy. Also, the “surprise question” (Would you be surprised if your patient died?) does not have sufficient predictive power for the implementation of PC in HI patients [2]. Life expectancy in HI patients is usually overestimated and PC does not seem appropriate, as it is often reduced to pure end-of-life care according to current understanding.

Any attempts to use mortality predictors to determine the start of palliative care result in few patients receiving PC for a very short time. This omission or delay is described as “prognostic paralysis.” Studies show that HI patients are assisted with PC much less frequently (7% vs. 49%) and for a significantly shorter time before death compared with oncology patients [3]. Today, however, PC should be introduced for all diseases on the basis of need rather than prognosis. PC is currently understood as a complement to, rather than an alternative to, basic treatment; PC does not become possible only when basic treatment is completed. This concept of gradual build-up of PC – according to the changing needs of patients and relatives – fits particularly well with the unpredictable course of heart failure.

Only hospice care is strongly prognosis-based and is primarily dedicated to the care of terminally ill people who are refusing life-sustaining therapies. It is important, however, that hospice care is not understood as the sole form of palliative care.

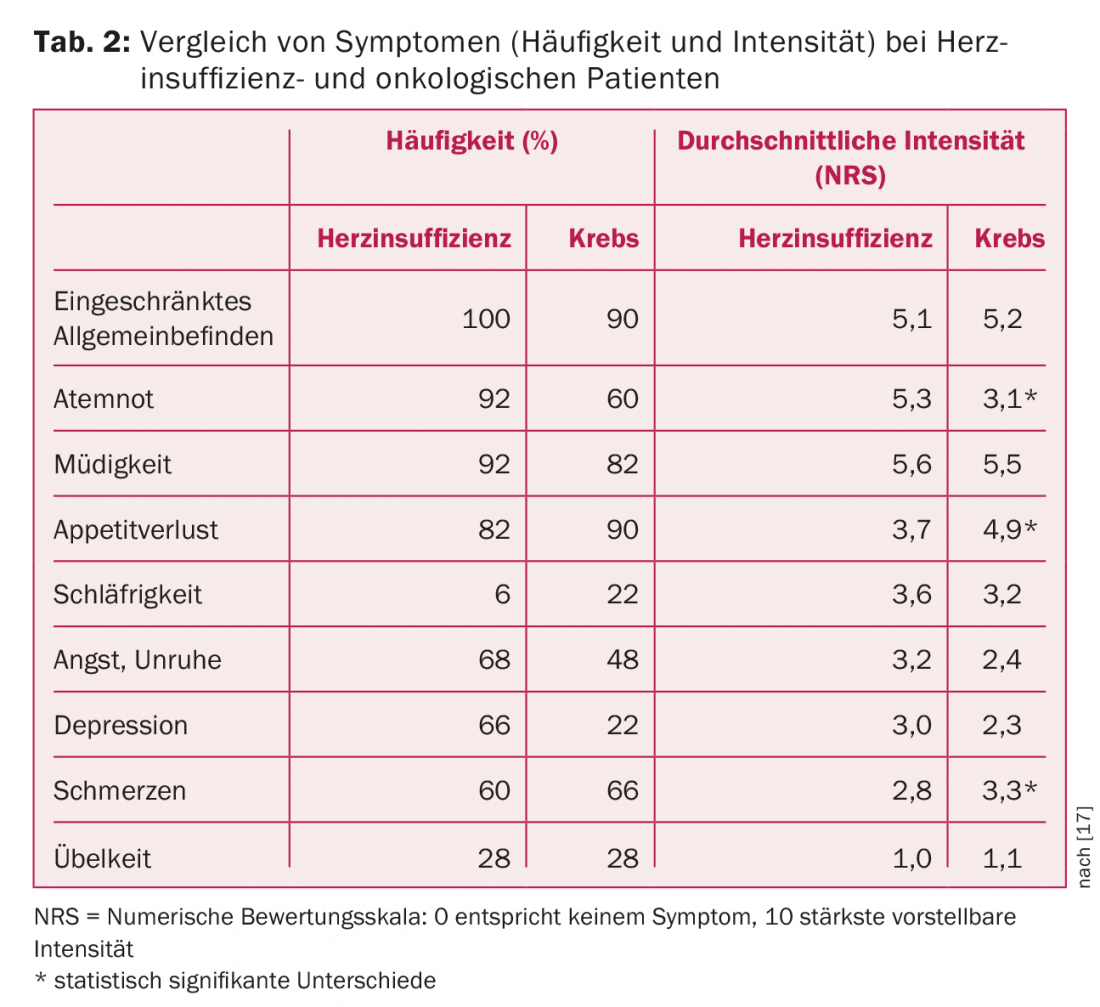

Symptom treatment: pain

A structured assessment of symptoms (e.g., using the Edmonton System Assessment System, ESAS) in patients with advanced HI showed that the type and frequency of symptoms in HI patients are not significantly different from those in other patient groups who use PC (Tab.2). For example, HI patients and oncology patients experience pain with equal frequency. These include both cardiovascular pain (e.g., angina, claudication) and pain resulting from secondary conditions (e.g., musculoskeletal pain). In patients with heart disease, the focus is too often limited to documentation and treatment of pectanginal symptoms. Noncardiac pain, on the other hand, is usually less perceived. In addition, there is uncertainty and justifiable reluctance to use analgesics in HI patients because the expected side effects (e.g., worsening renal insufficiency or the risk of sodium retention) may promote decompensation.

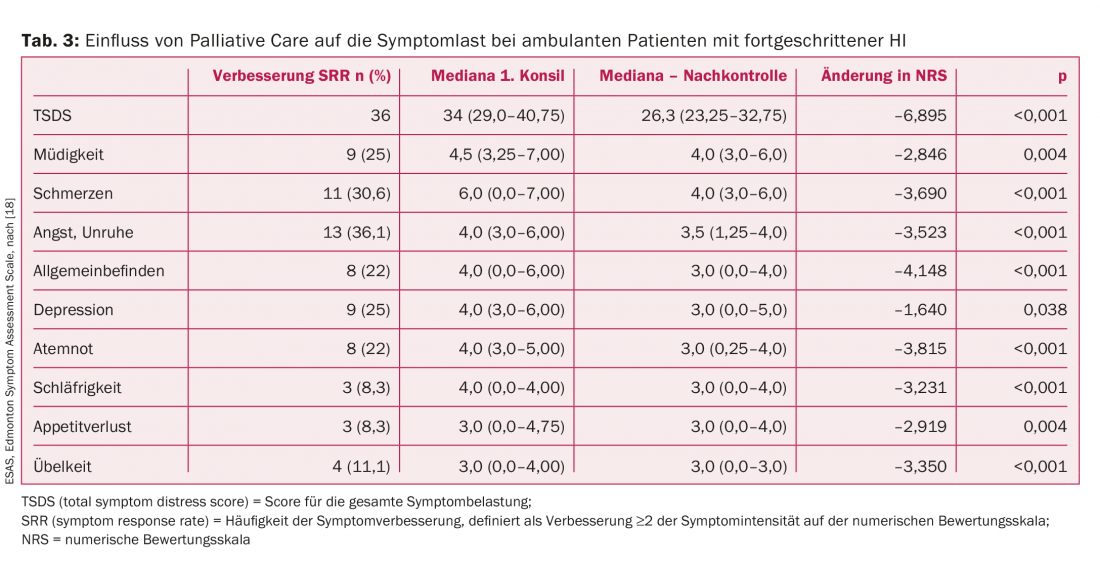

It is well documented that PC effectively improves general well-being and, in particular, pain symptoms (tab. 3) . A painkiller that is harmless from a cardiological point of view is paracetamol. It does increase the risk of hypertension, but an increased risk of HI decompensation has not been demonstrated [4]. According to recommendations of cardiology societies, reasonable opiate-based pain management should be preferred in HI patients. However, many physicians caring for HI patients lack experience prescribing opioids as chronic pain medication, so patients are often denied such therapy.

Symptom treatment: shortness of breath

There is also room for improvement in the symptomatic treatment of dyspnea, the cardinal symptom of HI. Of course, the primary focus is on optimal preload and afterload reduction and control of volume status using diuretics. In daily practice, however, a palliative therapeutic approach is rarely attempted even in cases of refractory respiratory distress. Opiates, for example low-dose morphine, can also be helpful in this case [5]. However, the safety of morphine use in acute heart failure has been questioned [6]. Therefore, morphine should preferably be used as part of a palliative therapeutic strategy. Opiate receptors have only recently been detected in the respiratory tract [7]. In the future, this could make the use of morphine as an inhalation therapy for the relief of respiratory distress attractive. However, studies in this regard are not yet available. Even nonpharmacologic approaches to therapy, such as a handheld fan aimed at the mouth and nose or a fan, can be surprisingly helpful. In patients with resting dyspnea with hypoxemia, oxygen administration should be attempted [8]. Respiratory distress represents the largest treatment gap of perceived symptoms (defined as lack of intervention despite awareness of the symptom). Because systematic assessments of the severity of dyspnea are not always performed, HI patients with severe, chronic dyspnea often go unrecognized [9].

Decision making

Decision making regarding consent to use available therapies is excellently ensured by cardiology teams. Involving a PC team can also be helpful in communicating about end-of-life decisions. Sensitive but open anticipation of disease progression and acceptance of death as the natural end of life are necessary to address any concerns. This attitude is particularly difficult to adopt in intensive care medicine, where people are accustomed to saving people from desolate situations and thus regard all death as potentially avoidable.

The problem of the restriction resp. Modification of ICD functions at the end of life is well known. The cardiology guidelines recommend that the possibility of modifying ICD functions at the end of life be addressed before implantation. However, as one survey shows, only just 4% of cardiologists who implant ICDs talk to their patients about ways to limit the activity of the device when inevitable death is approaching in an anticipatory manner [10]. Therefore, ICD aggregates remain fully active during the dying process in the majority of terminal patients. This leads to unnecessary and pointless shock therapy that compromises the quality of dying. Up to 20% of these patients experience painful shock discharges in the last days or even hours of life [11]. However, the decision-making process regarding restriction of ICD activity is complex because of the need to communicate openly about dying [12]. Often, such decisions are also subject to dynamics. As the course of the disease changes or the mental state changes, these decisions must be negotiated repeatedly. Other ICD functions, such as antitachycardia pacing or pacing, can remain active because they do not affect the quality of dying.

Networking

People with advanced, terminal HI are treated by different specialists at the same time, which in practice often leads to the establishment of complex and costly therapies, although these can no longer bring any benefit to the patient. In the latest models of integrated care, a specialist, often a nurse, acts as a coordinator on the treatment team, involving other members as needed (primary care physician, heart failure cardiologist, palliative care physician, psychologist, etc.). The aim is not only to facilitate access to necessary consultations for patients who are often elderly, but also to avoid unnecessary treatment.

Support (assistance)

Patients and their relatives and close confidants have different needs for communication about the further course of the disease. Sufferers are more interested in disease and symptom management, whereas relatives are more interested in impending risks and possible patterns of deterioration and impending death. PC is especially important to prepare relatives for such scenarios. Discontinuation of ongoing and life-prolonging therapies should be well communicated to avoid creating the impression that necessary therapies are being withheld or that patients are no longer being treated at all.

End of life

Recurrent decompensations usually lead to frequent emergency rehospitalizations in medical departments and intensive care units, even when the disease has already reached the terminal stage. On re-entry, there is often a change of treatment team, sometimes hospital, and the rapid achievement of euvolemia and expeditious discharge herald the beginning of the next sequence of therapy. Such a revolving door effect makes it difficult to create and consistently follow a treatment plan. When the “door” turns quickly, the patient often fails to see the attending cardiologist or primary care physician between decompensations.

A palliative consultation can be helpful here to introduce meaningful therapeutic approaches. Symptom-focused therapy at home, in a palliative care unit, or in a medical/cardiology department usually better meets the patient’s wishes in refractory HI than a desperate search for a new escalation of therapy. An important task for HI patients is also the precautionary creation of a living will. However, the specific aspects of caring for HI patients (e.g., dealing with ICD) are often not addressed in them.

For care at home (if that is the desired place of care and possibly also of death), it is important to discuss the procedure in crisis situations at an early stage. If death is imminent, the shock function of the ICD should be switched off after the patient has given his or her consent. If this is not the case or a programmer is not available to deactivate the ICD, a medical magnet can be used to deactivate the ICD on site. By taping the magnet directly over the ICD unit, impending shock delivery and antiarrhythmic therapies can be suppressed during the dying process. It is recommended to leave a magnet at the place of care. However, this intervention is too burdensome for relatives, and they should not be expected to use the magnet. However, if emergency services, a primary care physician, or palliative care is notified, they can perform the deactivation without delay [13].

Summary

Patients with advanced heart failure suffer from many symptoms, not just heart-specific ones, that can be identified and treated by incorporating palliative care. Crucial to the effectiveness and quality of care is good and close collaboration between cardiology and palliative care teams. The structures needed to ensure optimal care for HI patients and their families have not yet been defined; such structures need to be created and reviewed. There is a great need for studies that clarify the needs of patients and the value of PC and examine the effectiveness of palliative interventions. The European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) and the Heart Failure Group (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology recently created a joint task force to address issues concerning PC in people with heart failure; for more information, see www.eapcnet.eu/Themes/Specificgroups/Heartdisease.aspx.

Literature:

- Brannstrom M, Boman K: Effects of person-centered and integrated chronic heart failure and palliative home care. PREFER: a randomized controlled study. Eur J Heart Fail 2014; 16(10): 1142-1151.

- Murray S, Boyd K: Using the “surprise question” can identify people with advanced heart failure and COPD who would benefit from a palliative care approach. Palliat Med 2011; 25(4): 382.

- Gadoud A, et al: Palliative care among heart failure patients in primary care: a comparison to cancer patients using English family practice data. PLoS One 2014; 9(11): e113188.

- Sudano I, et al: Acetaminophen increases blood pressure in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation 2010; 122(18): 1789-1796.

- Ekstrom MP, Abernethy AP, Currow DC: The management of chronic breathlessness in patients with advanced and terminal illness. BMJ 2015; 349: g7617.

- Peacock W, et al: Morphine and outcomes in acute decompensated heart failure: an ADHERE analysis. Emerg Med J 2008; 25(4): 205-209.

- Krajnik M, Jassem E, Sobanski P: Opioid receptor bronchial tree: current science. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2014; 8(3): 191-199.

- Shah AB, et al: Failing the failing heart: a review of palliative care in heart failure. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2013; 14(1): 41-48.

- Kavalieratos D, et al: Comparing Unmet Needs between Community-Based Palliative Care Patients with Heart Failure and Patients with Cancer. J Palliat Med 2014; 17(4): 475-481.

- Marinskis G, van Erven L: Deactivation of implanted cardioverter-defibrillators at the end of life: results of the EHRA survey. Europace 2010; 12(8): 1176-1177.

- Matlock DD, Stevenson LW: Life-saving devices reach the end of life with heart failure. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2012; 55(3): 274-281.

- Hill L, et al: Patients perception of implantable cardioverter defibrillator deactivation at the end of life. Palliat Med 2014 Sep 19. pii: 0269216314550374. [Epub ahead of print]

- Sobanski P, Jaarsma T, Krajnik M: End-of-life matters in chronic heart failure patients. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2014; 8(4): 364-370.

- Goodlin SJ, et al: Consensus statement: Palliative and supportive care in advanced heart failure. J Card Fail 2004; 10(3): 200-209.

- Eychmüller S: [SENS is making sense – on the way to an innovative approach to structure Palliative Care problems]. Therapeutic Review 2012; 69(2): 87-90.

- Hupcey JE, Penrod J, Fenstermacher K: A Model of Palliative Care for Heart Failure. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2009; 26(5): 399-404.

- O’Leary N, et al: A comparative study of the palliative care needs of heart failure and cancer patients. Eur J Heart Fail 2009; 11(4): 406-412.

- Evangelista LS, et al: Does the type and frequency of palliative care services received by patients with advanced heart failure impact symptom burden? J Palliat Med 2014; 17(1): 75-79.

CARDIOVASC 2015; 14(2): 19-23