Suicidality is most often associated with mental illness, especially depression. Often suicidality “hides” behind somatic and other medical complaints. But a suicidal threat must be detected early and appropriate measures taken.

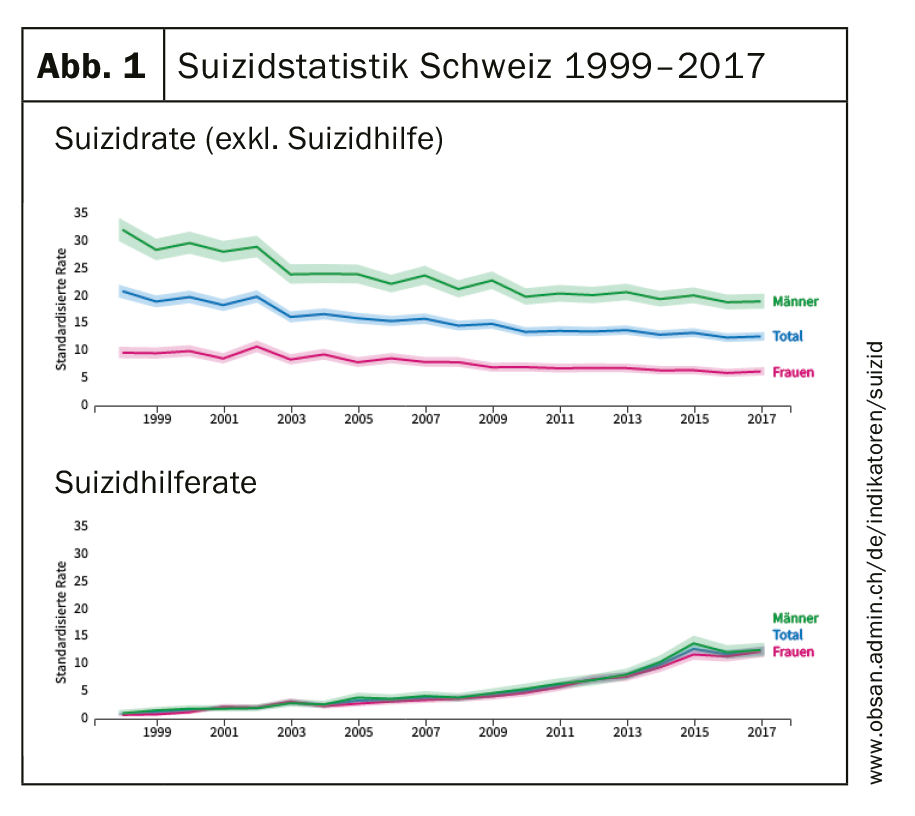

Suicidality is most often associated with mental illness, especially depression. A suicide risk wants to be recognized early on so that appropriate measures can be taken. The incidence of suicides (excluding assisted suicides) in Switzerland has continuously decreased slightly over the past 20 years, although the total number of suicides has increased slightly since 2005 as a result of the sharp increase in assisted suicides (Fig. 1). With about 1000 suicides per year, there are still three to four times more deaths by suicide than by traffic accidents in Switzerland.

Single men of older age (70 years and older) are particularly at risk. Among the 1043 completed suicides in 2017, hanging (17%), falls from heights (13.4%), and firearms (9.6%) stood out as the most common methods of suicide, whereas poisoning played a role in only 6% of suicides, roughly halving the 1999 figures. Drowning has also decreased in importance and frequency.

Differentiation into three groups

Three main groups of people with a clearly increased risk of suicide can be identified: People with mental illnesses, people in acute crisis situations resulting from situational, life-historical-biographical or traumatic changes, and people who have already reacted suicidally once in their lives or have had suicide attempts and suicidal crises [1].

- People with mental illness: We know from psychological autopsies after suicides [2] that 90% of those affected showed symptoms of mental illness before their death. The most frequent disorders were affective disorders (43%), especially depression, followed by addictive disorders, especially alcohol (26%), personality disorders (16%), psychotic disorders (9%), and adjustment disorders, including alcoholism. Anxiety and somatoform disorders (6%). 30-40% suffered from a somatic disease at the time of suicide, especially carcinomas and chronic pain syndromes.

- People in crisis situations: These frequently include relationship crises or the loss of a partner. Offenses often in the professional context as well as the loss of social, cultural, political living space, identity crises, chronic unemployment and the period after leaving a hospital, especially a psychiatric ward.

- People who have already reacted suicidally once in their lives: Suicidal people often experience their unbearable mental distress, also described as “mental pain”, as traumatization, which is stored in their experience and actions and can be reactivated as “suicidal mode” at each next suicidal crisis [3]. Not surprisingly, “mental pain” (Mental Pain), is a recurring theme in suicide notes.

Attitudes and models of suicidality

Dealing with the phenomenon of suicidality can be characterized by two opposing poles of action: Omnipotence (“S. is not an issue in my practice,” “S. does not occur in my practice.”) and Powerlessness (“I can’t prevent S. anyway”, “S. scares me…”); both attitudes do not do justice to suicidal people and prove to be unhelpful or even fatal in practice. People in suicidal crises generally do not want to die and certainly do not “like” to kill themselves. They are much more likely to be unable to endure their lives in the acute crisis, not wanting to go on living “like this” and therefore often desperately seeking ways out to end their emotional distress. Thus, if there is even the slightest suspicion that suicidality may be present in a patient, this should be addressed immediately. An antiquated notion that people who are approached about suicidal thoughts are motivated to do so “all the more” has long been proven to be a myth! Similarly, the presence of suicidal ideation alone does not predict possible subsequent suicidal acts.

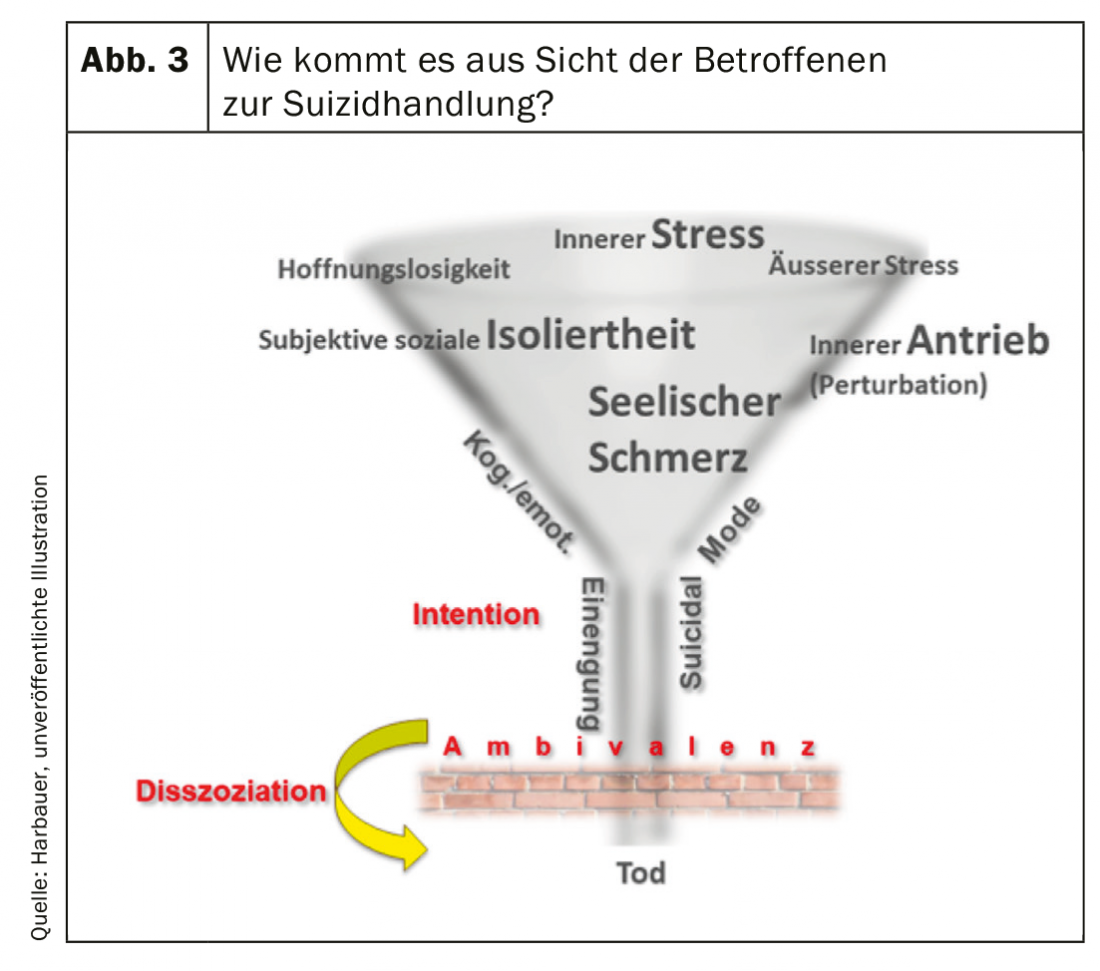

It may be helpful to use some models for understanding people in suicidal crises. These often subjectively experience their psychological problems as three times “u”, such as: unbearable (mental pain), infinite (long lasting) and inescapable (uncontrollable). According to Shneidman’s cube model [4], the probability of suicide increases linearly-summatively: the higher the mental pain, the greater the psychological pressure (external stressors) and the higher the inner turmoil (perturbation) in the affected person. According to an interpersonal theory [5], acute suicidality occurs frequently in cases of loss of belonging (loneliness) combined with the subjective perception of being a burden to oneself and others and the feeling of hopelessness about this state.

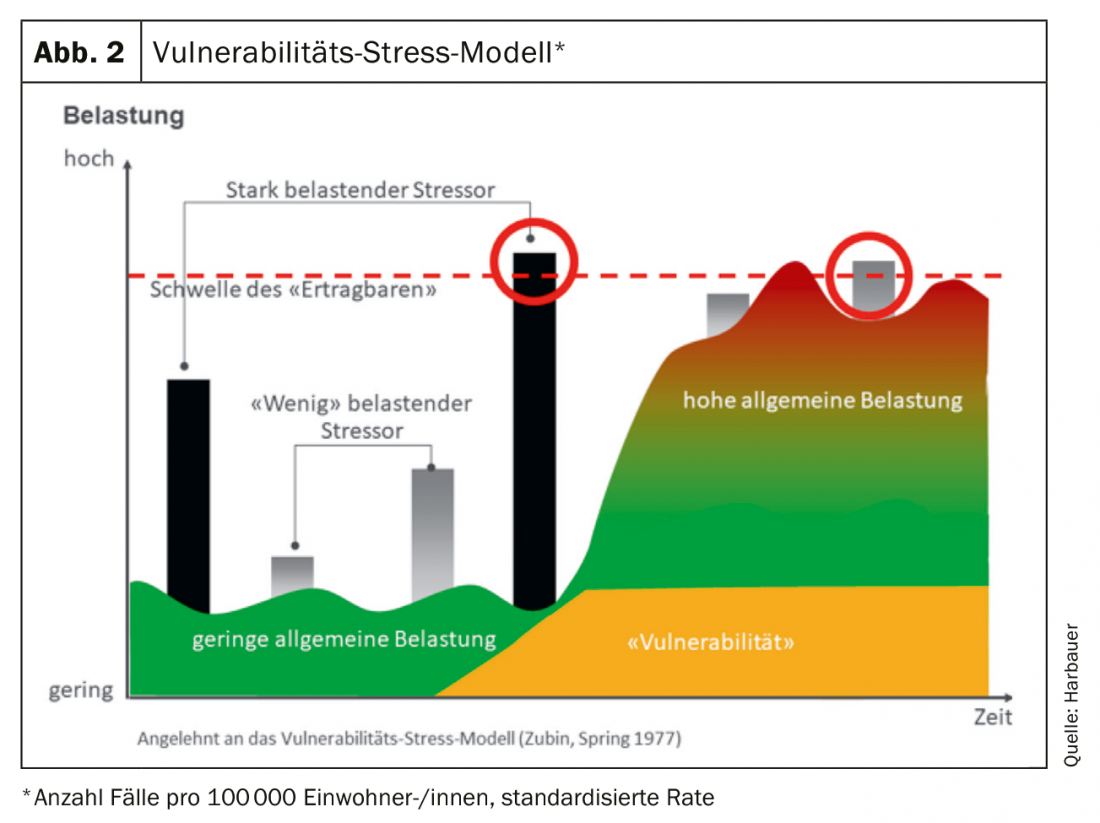

Suicide risk results not only from the current situation (life event or mental illness) as a “state” variable, but also from often congenital or early biographically acquired characteristics that increase vulnerability or impulsivity (“trait” variables), such as consequences of abuse or neglect, underlying neurological diseases or traumatic brain injury, family history of substance abuse, or family history of violent suicide. The latter are associated with decreased serotonergic activity [6]. Conversely, people with elevated serotonergic activity or other protective traits, often genetically determined, do not have the capacity to carry out suicide at all.

So far, no evidence has been found for an all-explanatory model. Nor is there a comprehensive, clinically “fit” model. In everyday clinical practice, crisis models have proven most useful for describing suicidal crises, e.g., the “traumatic crisis” [7] following sudden events or the “developmental crisis” [8], which manifests itself days to weeks after the triggering event:

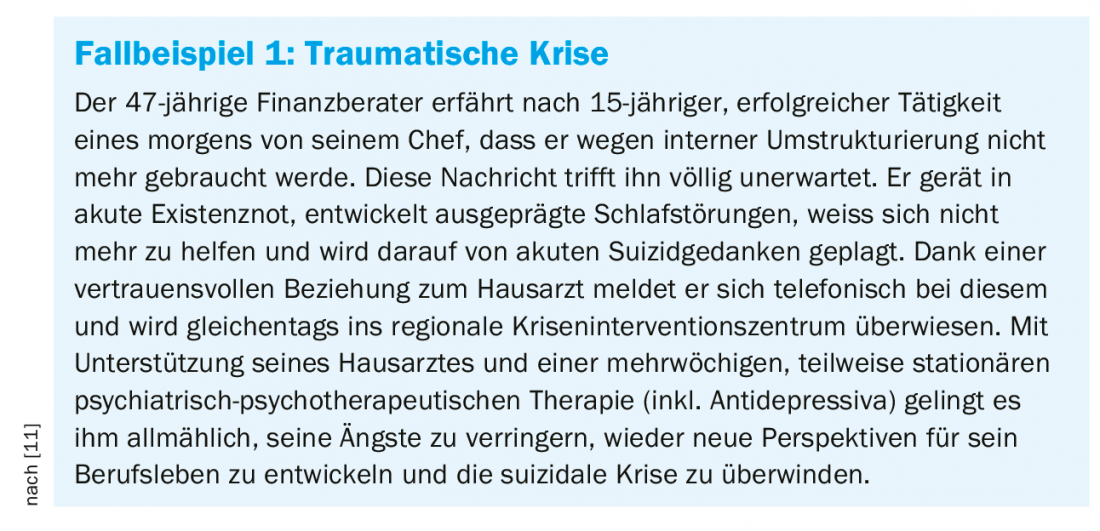

In a traumatic crisis, the event is nameable, and the stress manifests abruptly. The acute stage in the experiential 4-6 week course is “early”, i.e., at the time when coping strategies have not yet been used. Examples of the causes of traumatic crises are natural disasters, physical experience of violence, death, illness, disability or they are in the context of relationship separations or infidelity.

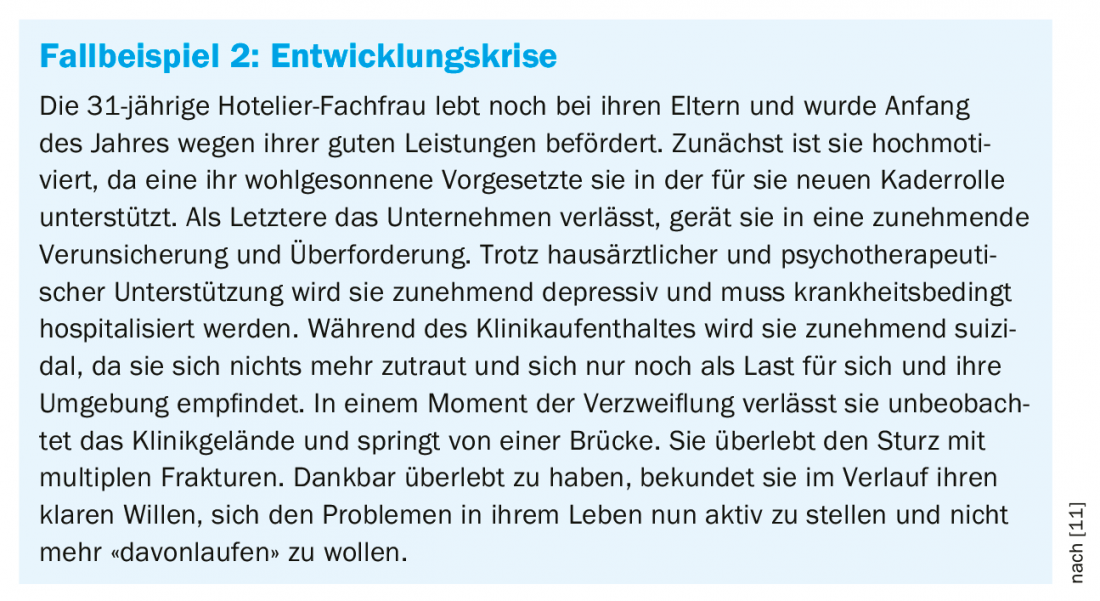

Traumatic crises generally result in suicide attempts or suicidal acts somewhat less frequently than developmental crises. The trigger is not always conscious in developmental crises, development occurs over days to weeks, duration is variable; the acute stage occurs “late” when available coping strategies are “exhausted.” Examples: Unemployment, job changes or promotions (even if missed: grievance), retirement, family, couple conflicts, leaving home, pregnancy, etc.

In most cases, a suicidal development crisis is preceded by drastic psychological problems (stressors), which the affected person tries to counter by mobilizing and using available coping measures. The situation is aggravated if the level of general stress is already high in the affected person and even more so if there is an increased vulnerability according to the stress vulnerability model [9] analogous to the trait model described above (Fig. 2) . It is then often not possible to defuse the stressor, and the strain remains. Other strategies also fail to cope with the problem until the person’s resources and energy reserves gradually run dry. If the individual “threshold of tolerability” is exceeded under this chronic stress, a state of emergency occurs which can subsequently lead to acute suicidal tendencies and, under certain circumstances, to suicidal acts.

Acute suicidality occurs when the threshold of tolerability is exceeded over a longer period of time, thus generating a chronic state of stress which is perceived by the affected person as an unbearable state of emergency and is unacceptable to the self. In this existential threat, the stress cascade is triggered and both flight and attack impulses are released. Before a suicidal act in the narrower sense occurs in the so-called “suicidal mode,” a number of other conditions are required in addition to those outlined in the cube model (e.g., the presence of “hopelessness” and subjective “social isolation”), which play a role in varying degrees of significance. Usually the suicidal intention is accompanied by strong ambivalence and only a “dissociative” state, often induced by lack of sleep, stress symptoms or mind-altering substances (e.g. alcohol, medication) “enable” the affected person to move from the initial intention (suicidal urge) into action (fig. 3).

Suicide prevention

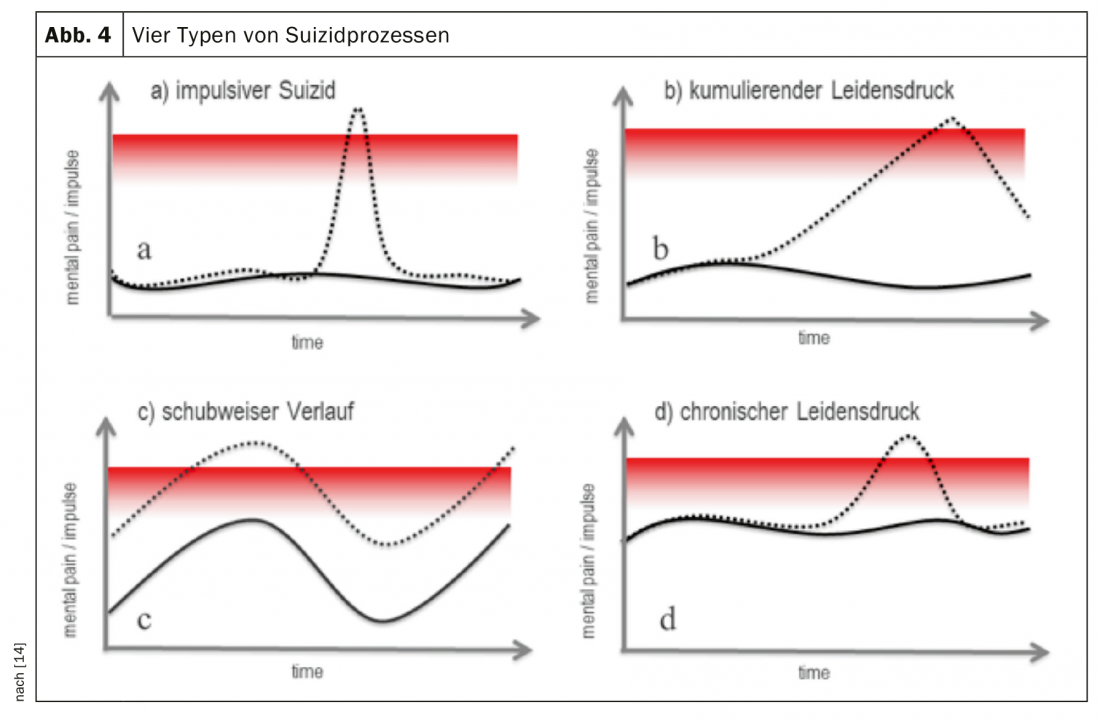

According to a phase-based model, 4 types of suicide processes can be distinguished. Impulsive suicide attempts and cumulative distress (a and (b) together comprise 20-40% of cases, of which more than 50% would be preventable with a bundle of suicide prevention measures. Suicide attempts and suicides in relapsing-remitting patients. (c) together comprise 50-70% of cases, of which about 50% would be preventable. The remaining 10% correspond to suicides in the wake of persistently high suicidality, which includes balance suicides (Fig. 4).

According to this vision, which is not unrealistic, a total of 400-500 of the current 1000 suicides per year could be prevented in Switzerland.

In suicide prevention, a distinction is made between primary, secondary and tertiary prevention measures: Primary prevention refers to measures that make it more difficult for suicidal people to access assistive devices or limit their availability. As part of a focus program on suicide prevention in the canton of Zurich, which has been running since 2015 on the basis of an expert report [10] the following potentially life-saving measures could be implemented, for example: Recalls of medicines from households in cooperation with pharmacies and drugstores, safety measures on bridges, towers and railroad tracks, as well as tailored training courses for multipliers, information brochures and other awareness-raising communication and networking measures (cf. www.suizidprävention-zh.ch).

Secondary prevention includes, in particular, treatment of the underlying illness that led to the suicidal crisis. As part of the national campaign “How are you?” (www.wie-gehts-dir.ch), with the slogan “Talking can save,” among others, around 25000 flyers were circulated in the canton of Zurich in 2017. A suicide prevention helpline has also been established.

As part of tertiary prevention, particular attention should be paid to follow-up care after suicide attempts. Since it is known that immediately after an inpatient stay in a psychiatric hospital there is an approximately 200-fold increased risk of suicide compared to the population average. Among other things, bridging conferences have been established to which therapists or primary care providers are invited to provide post-inpatient care. It is also important to focus on family members (see www.trauernetz.ch).

Access to people in suicidal crises

Interviews following suicide attempts showed that, in addition to mental illness, relationship conflicts were among the most common problems leading to suicide attempts, accounting for 71%. Also, the latter are the most common “triggers” for a completed suicidal act at 45% [12]. However, communicating their emotional distress is difficult for many suicidal people, partly because they cannot imagine any benefit, are afraid of the consequences, or have had bad experiences in communicating with helpers. However, not being able to communicate unbearable emotional pain correlates with suicidal risk and lethality [13].

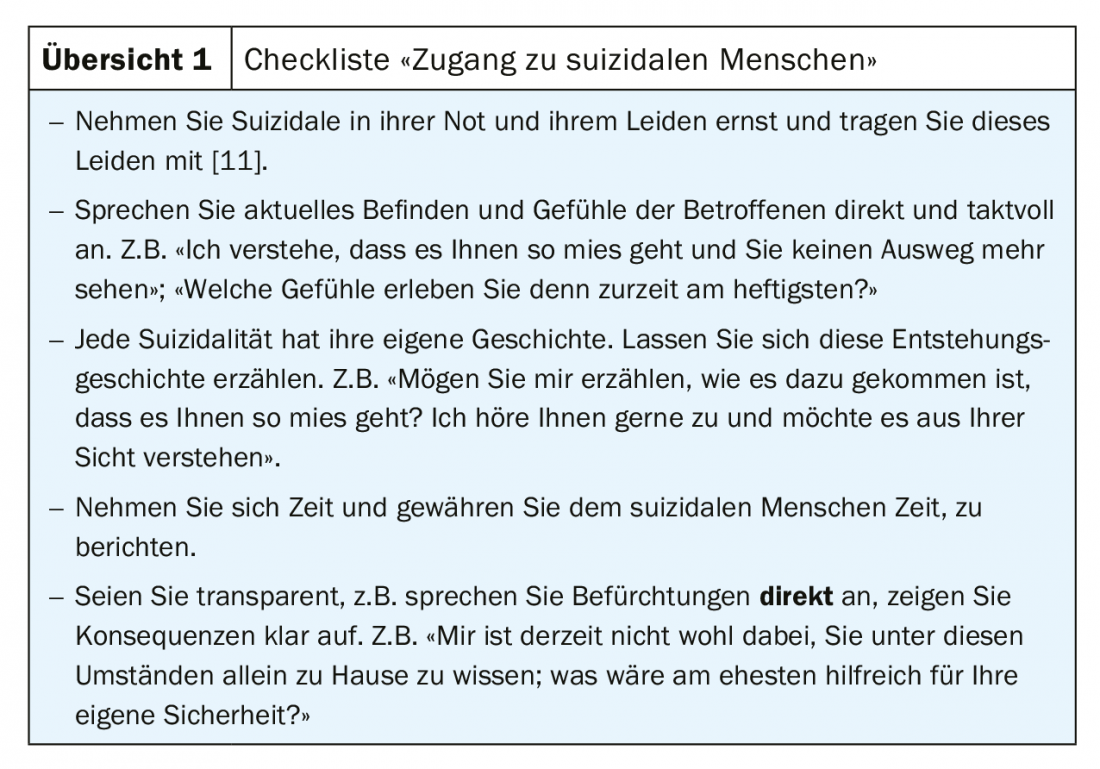

Unfortunately, people in suicidal crises often experience rejection or taboo. The environment also often reacts with helplessness, excessive demands or even anger. In their private environment, but also on the part of professionals, they often experience that people look away or listen, that their complaints are trivialized, or that they receive well-intentioned advice (sleep on it, wait and see). In contrast, people in suicidal crises want to be addressed directly, to have time taken for them, to be listened to, to have their distress/problems taken seriously, to be shown understanding and to be asked. A “collaborative aproach” [14], i.e., a collaborative, cooperative approach in which physician and patient form a shoulder-to-shoulder relationship and jointly consider the state of suicidality, has proven particularly helpful in practice. This makes it easier for the primary care provider to address his or her own feelings and fears (e.g., regarding safety) with the individual (Overview 1).

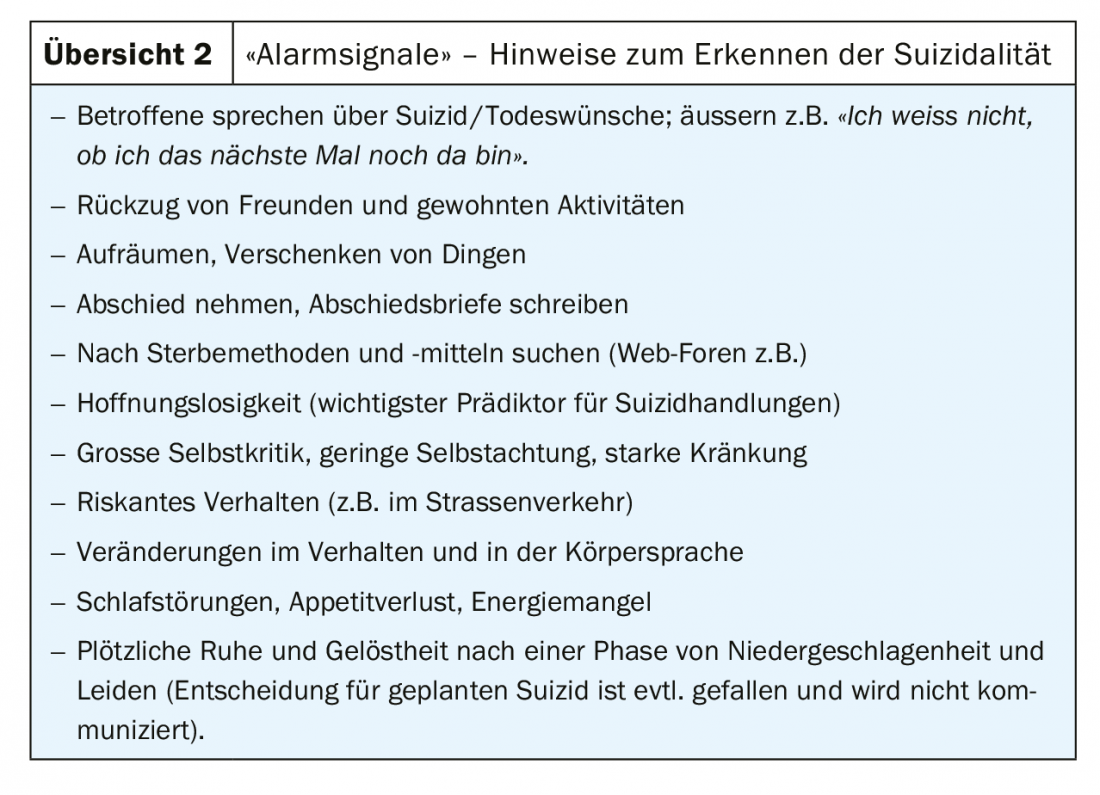

According to the guidelines for the treatment of affective disorders, the following measures are recommended for the management of suicide risk: a) Directly addressing the issue of suicide and b) Intensification of time commitment and therapeutic commitment. The following indications can be understood as possible alarm signals and addressed tactfully (Overview 2).

Assessment of suicidality – what has worked clinically?

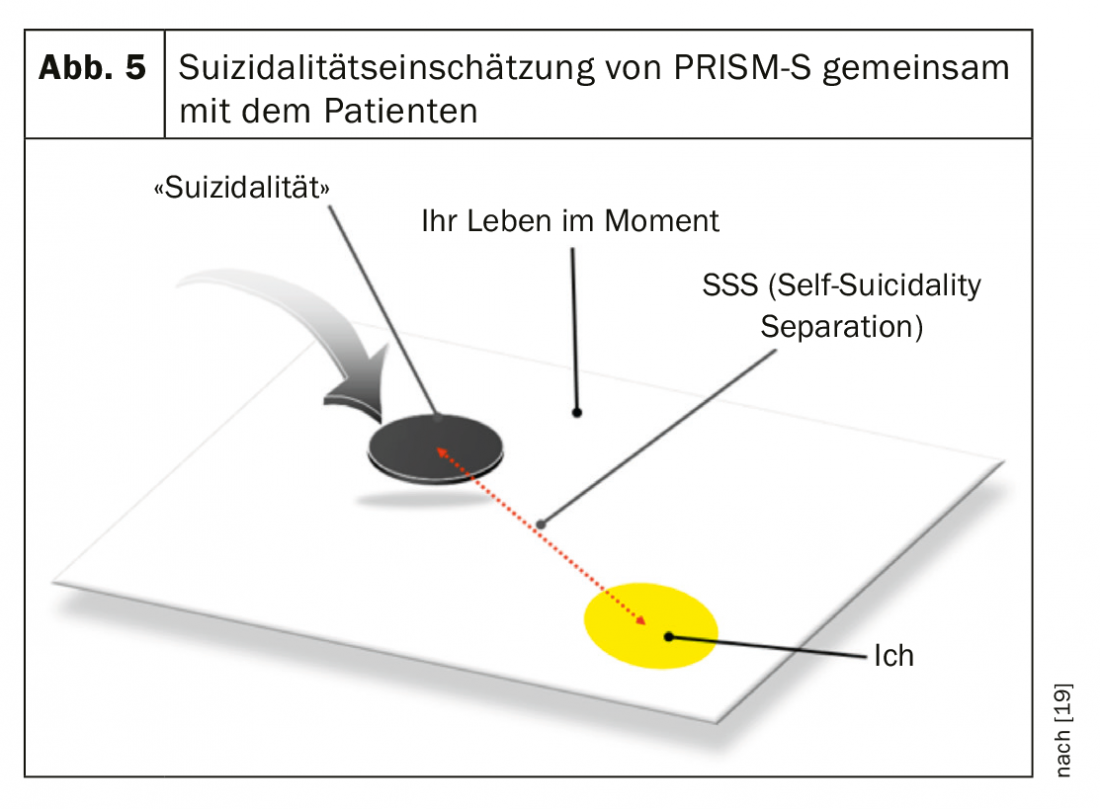

It is helpful in assessing a concrete suicide risk to check what has been said for conclusiveness and comprehensibility. Using a questionnaire or asking a single, general question is usually not sufficient for this purpose. Suicide attempts and suicidality can be more effectively reduced by directly addressing suicidal people about their potential suicidality – not just indirectly through their symptoms of hopelessness, anxiety, or depression. To address this, the clinical visualization instrument PRISM-S (Pictorial Representation of Illness and Self Measure – Suicidality) was developed [15] (Fig. 5) PRISM-S helps to reliably assess suicidality in a patient-centered manner and within a useful time.

As demonstrated in a study of adults up to 65 years of age, PRISM-S can reliably measure current suicide risk in less than five minutes. The standardized instrument consists of a white A4 metal plate with a yellow dot seven centimeters in diameter in the lower right corner and a black plastic disc. In keeping with the collaborative “posture of a shoulder to shoulder” [14], ideally one sits next to the patient or, as is often the case in family practices, at a table at right angles to each other. The patient is told that the plate represents his “life” and the yellow circle represents “himself” (wording: the yellow dot represents “you”). Then the black, magnetic disc five centimeters in diameter is shown, introduced as a representation of the “urge to take one’s own life.” Finally, the patient is asked to place the “suicidality disc” with the question: “What place in your life does the urge to take one’s own life currently occupy? The distance between the yellow dot (patient) and the “suicidality slice” is the quantitative measure that can be described as “risk level of suicide”. The patient is then asked, “What does this mean to you when you put the urge to take your own life in this place?” The spontaneously following, concrete detailed expressions are qualitatively evaluated and offer an immediate and direct access to the background of suicidality. The PRISM-S visual instrument measures with comparable reliability to other standardized scales, as shown in a validation study and an RCT study [15], but does not employ the usual (and often unpopular) “paper & pencil handling”.

In most cases, PRISM-S gives a very good impression of the patient’s current level of risk in two to three minutes. Specifically, the patient visualizes on the board their own relationship to their urge to suicide. The black disk is positioned by the patients – according to the authors’ assumption – at the point where the unbearable extent of suffering on the one hand and their available resilience on the other hand meet. It expresses, so to speak, the current balance of the two tendencies for or against the suicidal act, which can be concretely addressed in dialogue with the patient. PRISM-S provides a visual impression in a simple way of the extent to which those at risk of suicide feel “threatened” themselves, or in other words, how much “resilience” or resources they are still supported by. The use of the PRISM-S instrument does not, of course, replace the medical-psychological interview, in which the experiences of the professionals and their “gut feeling” are incorporated. In clinical practice, the use of PRISM-S in adults (18-65 years) has now proven successful in many psychiatric institutions in Switzerland.

Take-Home Messages

- People in crisis situations with mental illness, and those who have already been suicidal once in their lives, are at increased risk of suicide.

- Suicidal states are often transient and accompanied by strong ambivalence. Suicidal acts usually occur only in a “dissociative” state of emergency.

- With a bundle of consistently applied suicide prevention measures, up to 50% of the 1000 suicides per year could theoretically be prevented in Switzerland in the future.

- When assessing a concrete suicide risk, it is helpful to address suicidal tendencies directly and to check what has been said for conclusiveness and comprehensibility, e.g., with the help of the PRISM S visualization instrument.

Literature:

- Wolfersdorf M: Suicide and suicidality from a psychiatric-psychotherapeutic perspective. In: Psychotherapie im Dialog, 13. jg., 2, 2012; 2-7.

- Arsenault-Lapierre G, et al: Psychiatric Diagnoses in 3275 Suicides: A Meta-Analysis BMC Psychiatry 2004; 4: 37.

- Orbach I: Mental Pain and Suicide J Psychiatry Relat Sci 2003; 40(3): 191-201.

- Shneidman ES: A psychological approach to suicide. In G. R. VandenBos & B. K. Bryant (Eds.), Master lectures series. Cataclysms, crises, and catastrophes: psychology in action. American Psychological Association 1987; 147-183.

- Van Orden KA et al: The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev 2010; 117(2): 575-600.

- Van Heeringen K: Stress-Diathesis Model of Suicidal Behavior. In: Dwivedi Y, ed. The Neurobiological Basis of Suicide. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press/Taylor & Francis 2012.

- Cullberg J: Crises and crisis therapy. Psychiatric Practice 1978: 25-30.

- Caplan G: Principles of preventive psychiatry. New York, London, Basic Books 1964.

- Zubin J, Spring B: Vulnerability: A new view of schizophrenia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 1977; 86(2): 103-126.

- Ajdacic V, et al.: Expertenbericht zu handen des Regierungsrates des Kantons Zürich. FSSZ Forum for Suicide Prevention and Suicide Research Zurich 2011.

- Dunkley C, Borthwick A, Bartlett RL, et al: Hearing the Suicidal Patient’s Emotional Pain: A Typological Model to Improve Communication. Crisis. The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention 2017; DOI: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000497.

- Stulz N, et al: Patient-Identified Priorities Leading to Attempted Suicide. Crisis 2018; 39: 37-46.

- Gvion Y, et al: Aggression-impulsivity, Mental Pain, and Communication Difficulties in Medically Serious and Medically Non-Serious Suicide Attempters. Compr Psychiatry 2014; 55(1): 40-50.

- Jobes DA: Managing Suicidal Risk. New York; Guilford 2006.

- Ring M, Harbauer G, Haas S, et al: Validation of the suicidality assessment instrument PRISM-S (Pictoral Representation of Illness Self Measure – Suicidality) [Validity of the suicidality assessment instrument PRISM-S (Pictoral Representation of Illness Self Measure – Suicidality)]. Neuropsychiatr 2014; 28(4): 192-197.

- Haas S, Stähli R: Prevention of mental illness. Basics for the Canton of Zurich. ISPM Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine, University of Zurich 2012.

- Haas S, Minder J, Harbauer G: Suicidality in old age-what can the family physician do? [Suicidality in the elderly – what the general practitioner can do]. Praxis (Bern 1994) 2014; 103(18): 1061-1066.

- Harbauer G, et al: Suicidality assessment with PRISM-S – simple, fast, and visual: a brief nonverbal method to assess suicidality in adolescent and adult patients. Crisis 2013; 34: 131-136.

- Meerwijk E: Direct Versus Indirect Psychosocial and Behavioural Interventions to Prevent Suicide and Suicide Attempts: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2016; 3(6): 544-554.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2020; 18(5): 10-16.