For four days, representatives of the neurosciences met in Barcelona for the 2018 ECNP Congress. A central theme was the influence of lifestyle and environmental factors on health. Prof. Dr. med. Undine Lang, Director of the University Psychiatric Clinics Basel, spoke about the connection between nutrition and depression.

Right at the beginning of her presentation at the ECNP Congress 2018 in Barcelona, Prof. Undine Lang, MD, Director of the University Psychiatric Clinics Basel (UPK Basel), made it clear: “We must not simply fight against the symptoms of depression, but look at the resources and factors that we can change in patients’ behavior.” This is because patients are primarily interested in issues that shape their daily lives and go beyond symptom reduction, he said. The focus on the patient perspective – an important vanishing point of this year’s congress – was thus echoed in Lang’s presentation on the relationship between depression and nutrition.

The lifestyle decides

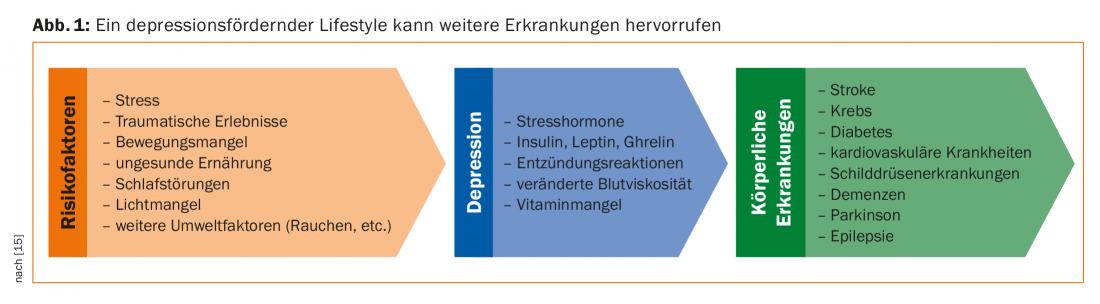

Lang’s research group is investigating complementary therapeutic approaches beyond SSNRIs that can be used to treat depressed people with few side effects and in a way that is close to everyday life. And supportive measures are needed: although pharmacological and psychotherapeutic care has greatly increased, the number of depressed patients is growing; pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy are only able to reduce half of the symptoms [1,2]. This suggests a strong influence of environmental risk factors [3]. Harmful environmental factors such as stress, traumatic experiences, low physical activity, sleep disturbances, light deficits, and an unhealthy diet can lead to depression. This multicausal disease has metabolic, cardiovascular, endocrinologic, and inflammatory implications. Thus, depression – or a depression-promoting lifestyle – is associated with comorbidities such as cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, stroke, or Alzheimer’s disease (Fig. 1). In turn, treatment of depression leads to a significant improvement in the outcome of the comorbid diagnosis, about threefold in Parkinson’s disease [4].

According to Prof. Lang, nutrition plays a special role in the therapeutic manipulation of environmental factors. Studies on the influence of the microbiome on health are booming. Since the turn of the millennium, their number has multiplied exponentially. Looking at heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes, one study concluded that 45% of all deaths could have been prevented with proper nutrition [5]. Studies also indicate the great importance of the microbiome in relation to depressive or anxious behavior [6].

The mysterious influence of psychobiotics

“The small intestine influences our behavior,” states Prof. Lang, pointing out that numerous diseases actually begin in the intestine. The microbiome may prove to be a breakthrough in clinical neuroscience. For example, positive results of fecal microbiota transplantation in autistic children give hope [7].

The gut microbiome consists of over 1014 microorganisms, which in turn belong to more than 1000 species. The microbiome is in constant exchange with the brain via the autonomic and enteric nervous systems (ENS), the neuroendorkrine and metabolic systems, and the immune system (“gut-brain axis”): Around 90% of all information flows from the gastrointestinal tract to the brain, and only 10% the other way around. Important neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine and GABA are produced in the intestine, which also influence mood. The exact effect of the “psychobiotics” is currently being researched to determine where to start therapeutically in the treatment of depression. It is known that the microbiome of depressed patients differs from that of healthy people.

Does the right diet reduce the risk of depression?

Several association studies suggest that unhealthy expressions of Western diet negatively influence the risk for depression. Eating refined foods, sweet drinks, fried goods, sausage or cookie snacks will harm [8,9]. A prospective cohort study of 87,600 postmenopausal women found that high glycemic index and low intake of lactose and fruits were associated with higher risk of depression [10]. On the other hand, a Japanese or Mediterranean diet, which includes a lot of olive oil, fish, fruits, vegetables, nuts, and unprocessed meat, is risk-reducing [8]. Vegetarians report significantly better mood compared to omnivores, interestingly despite reduced intake of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids [11]. The results of a multicenter quasi-experimental study indicate that there is a relationship between vegan diet, well-being, and productivity [12]. However, Prof. Lang urges caution: “Many studies are retrospective, so the actual influence of nutrition can hardly be considered in isolation.

In contrast, the SMILES study published in 2017 provides exciting results, the first to examine the effects of a nutritional therapy intervention in severely depressed patients in a prospective randomized controlled setting. Compared to the control group receiving psychotherapy (sometimes in combination with pharmacotherapy), the group treated with nutritional therapy achieved a remission of 32% (defined as <10 on the MADRS scale) after three months [13].

In principle, nutritional therapy care for patients with depression has proven to be very useful. For example, nutrition coaching over two years in an elderly patient population led to a reduction in depressive symptoms and a lower rate of rehospitalization [14]. Nevertheless, more prospective randomized clinical trials are needed to investigate the reciprocal relationship between diet and depression and therapeutic options based on these findings.

Source: 31st ECNP Congress, October 6-9, 2018, Barcelona (E).

Literature:

- Casacalenda N, Perry JC, Looper K: Remission in major depressive disorder: a comparison of pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, and control conditions. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159(8): 1354-1360.

- Jorm AF, et al: Has increased provision of treatment reduced the prevalence of common mental disorders? Review of the evidence from four countries. World Psychiatry 2017; 16(1): 90-99.

- Marx W, et al: Nutritional psychiatry: the present state of the evidence. Proc Nutr Soc 2017; 76(4): 427-436.

- Shen CC, et al: Risk of Parkinson disease after depression: a nationwide population-based study. Neurology 2013; 81(17): 1538-1544.

- Micha R, et al: Association Between Dietary Factors and Mortality From Heart Disease, Stroke, and Type 2 Diabetes in the United States. JAMA 2017; 317(9): 912-924.

- Lyte M: Microbial Endocrinology in the Microbiome-Gut-Brain Axis: How Bacterial Production and Utilization of Neurochemicals Influence Behavior. PLoS Pathog 2013; 9(11): e1003726.

- Kang D, et al: Microbiota Transfer Therapy alters gut ecosystem and improves gastrointestinal and autism symptoms: an open-label study. Microbiome 2017; 5: 10.

- Ruusunen A, et al: Dietary patterns are associated with the prevalence of elevated depressive symptoms and the risk of getting a hospital discharge diagnosis of depression in middle-aged or older Finnish men. J Affect Disord 2014; 159: 1-6.

- Jacka FN, et al: Diet quality and mental health problems in adolescents from East London: a prospective study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2013; 48(8): 1297-1306.

- Gangwisch JE, et al: High glycemic index diet as a risk factor for depression: analyses from the Women’s Health Initiative. Am J Clin Nutr 2015; 102: 454-463.

- Beezhold BL, Johnston CS, Daigle DR: Vegetarian diets are associated with healthy mood states: a cross-sectional study in seventh-day adventist adults. Nutr J 2010; 9: 26.

- Agarwal U, et al: A multicenter randomized controlled trial of a nutrition intervention program in a multiethnic adult population in the corporate setting reduces depression and anxiety and improves quality of life: the GEICO study. Am J Health Promot 2015; 29(4): 245-254.

- Jacka FN, et al: A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the SMILES trial). BMC Medicine 2017; 15: 23.

- Stahl ST, et al: Coaching in healthy dietary practices in at-risk older adults: a case of indicated depression prevention. Am J Psychiatry 2014; 171(5): 499-505.

- Lang UE, Walter M: Depression in the Context of Medical Disorders: New Pharmacological Pathways Revisited. Neurosignals 2017; 25: 54-73.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2018; 16(6): 48-49.