The most common mental disorders in oncology patients include adjustment disorders, anxiety disorders, affective disorders, cancer-related fatigue, and delirium. Psychological stress must be identified at an early stage and psycho-oncological support services should be offered in a timely manner. Routine psycho-oncological assessment and, if necessary, combined psychopharmacological-psychotherapeutic treatment should be part of any treatment plan. Psycho-oncological interventions should be offered according to individual needs in all phases of tumor treatment.

Cancer is an umbrella term for a variety of malignancies that can affect any organ or system of the body and have varying prognoses depending on the time of diagnosis, severity, and location. In Switzerland, the incidence of cancer has been increasing in recent years. According to the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (SFSO), approximately 38,500 people are diagnosed with cancer each year, although the distribution and frequency of tumor disease varies by gender. In women, breast cancer is the most common tumor disease with 5732 new cases, while in men, prostate cancer is the most common with 6236 new cases annually. Cancer is the second leading cause of death in both sexes after cardiovascular disease [1].

Thanks to tremendous medical and therapeutic advances in oncology through improved early detection, diagnosis and treatment options, survival rates for most tumor types have improved significantly in recent years. However, patients have to cope with a debilitating and stressful therapy phase, which in some cases can have lasting physical and psychological consequences and after-effects. The quality of life of affected patients is therefore given central importance in oncological treatment. Important tasks of the consultation and liaison service in the treatment of oncological patients are psycho-oncological diagnostics as well as psychosocial counseling and support in coping with the disease to improve mental health and functional impairment [2].

The most common psychological distress encountered in consultative psychiatric and psycho-oncology practice includes adjustment disorders, anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, as well as sleep disorders, fatigue (Cancer-related Fatigue), and delirium. This article is devoted to the most common mental disorders in the treatment of oncology patients in the consultation and liaison service.

Psychological stress of oncological diseases

The unexpected confrontation with a tumor disease means an existential crisis for many of those affected, which requires an enormous amount of adjustment. Impending diagnostic interventions, therapies and their effects on physical integrity and on the social and professional environment trigger a great deal of uncertainty, anxiety and feelings of being overwhelmed and helpless. Side effects from tumor therapy (chemotherapy and radiotherapy, surgical procedures) can be perceived as very stressful and affect important everyday functions. Depending on the tumor disease, life may be threatened, chronic pain, physical immobilization, but also visible physical stigmata (e.g., after mastectomy), which radically change the living environment of those affected and lead to impairments in physical and psychological performance. Typically, the highest levels of stress can be observed in patients suffering from oncological disease with poor prognosis and high mortality [3–5].

Prevalence rates of mental disorders in oncology patients.

The prevalence rates for mental disorders in tumor patients found in the literature vary greatly depending on the patient groups studied and the study instruments used. According to current studies, approximately 25-40% of all oncological patients develop a mental disorder requiring treatment during the course of tumor treatment [5–8]. Several studies indicate that patients with tumors of the lung, gynecologic tumors, breast Ca, brain and ENT tumors, and gastrointestinal tumors show the highest levels of distress, whereas patients with prostate Ca develop the fewest psychological comorbidities [9,10]. In addition, in a recently published comprehensive study (n=304 118). [11] found that oncology patients were at increased risk for developing a mental disorder as early as 10 months before a cancer diagnosis, the rate for mental comorbidities increased significantly within the first week after diagnosis, then decreased significantly, with the rate for mental comorbidities remaining elevated until 10 years after a tumor diagnosis.

Etiology of mental disorders

A distinctive feature of psycho-oncology care is that the emotional experience or behavior of patients with oncology is, in most cases, not a pathological disorder, but largely a natural stress response to the tumor disease and treatment. Depending on available resources, feelings of grief, despair, helplessness and hopelessness, fear of loss of autonomy and dependency, and/or being overwhelmed with existential issues can lead to enormous psychological stress and even the development of a mental disorder. Particularly critical phases for the manifestation of mental disorders include the time of diagnosis, the occurrence of a relapse or tumor progression. However, clinical experience shows that affected patients may be psychologically distressed at any point during tumor treatment, even long after tumor therapy has been completed [12].

Etiopathogenetic considerations of the development and manifestation of psychological distress in oncology patients are based on multidimensional and multifactorial relationships. Pain, a high physical symptom burden, Cancer-related Fatigue (CrF) as well as anamnestically known psychological disorders, for example, can promote the occurrence of psychological disorders in cancer patients. Other vulnerability factors for the development of a mental disorder during the course of tumor treatment include sociodemographic factors such as age, female gender, social support, education level, and socioeconomic status, as well as medical factors such as tumor dignity, tumor stage, and exposure to tumor-specific treatment [7,10]. A recently published study by Meyer et al. (2015) [4] impressively illustrates that depression risk increases with disease progression. In summary, psychological disorders in oncological patients can have far-reaching consequences on treatment success and mortality [13], massively impair quality of life, and lead to increased postoperative complications, longer hospitalizations, and also reduced compliance with treatment [14].

Diagnostics

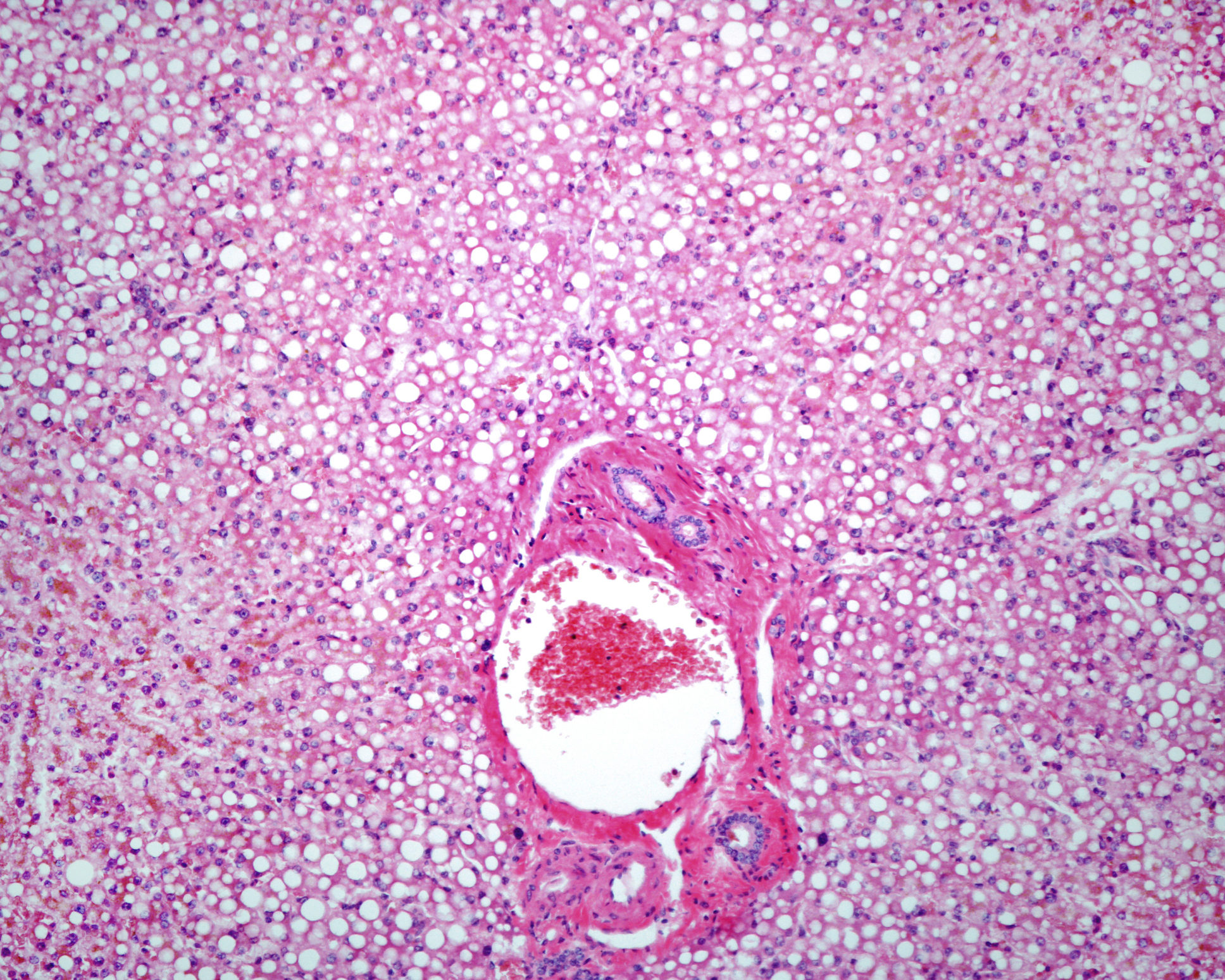

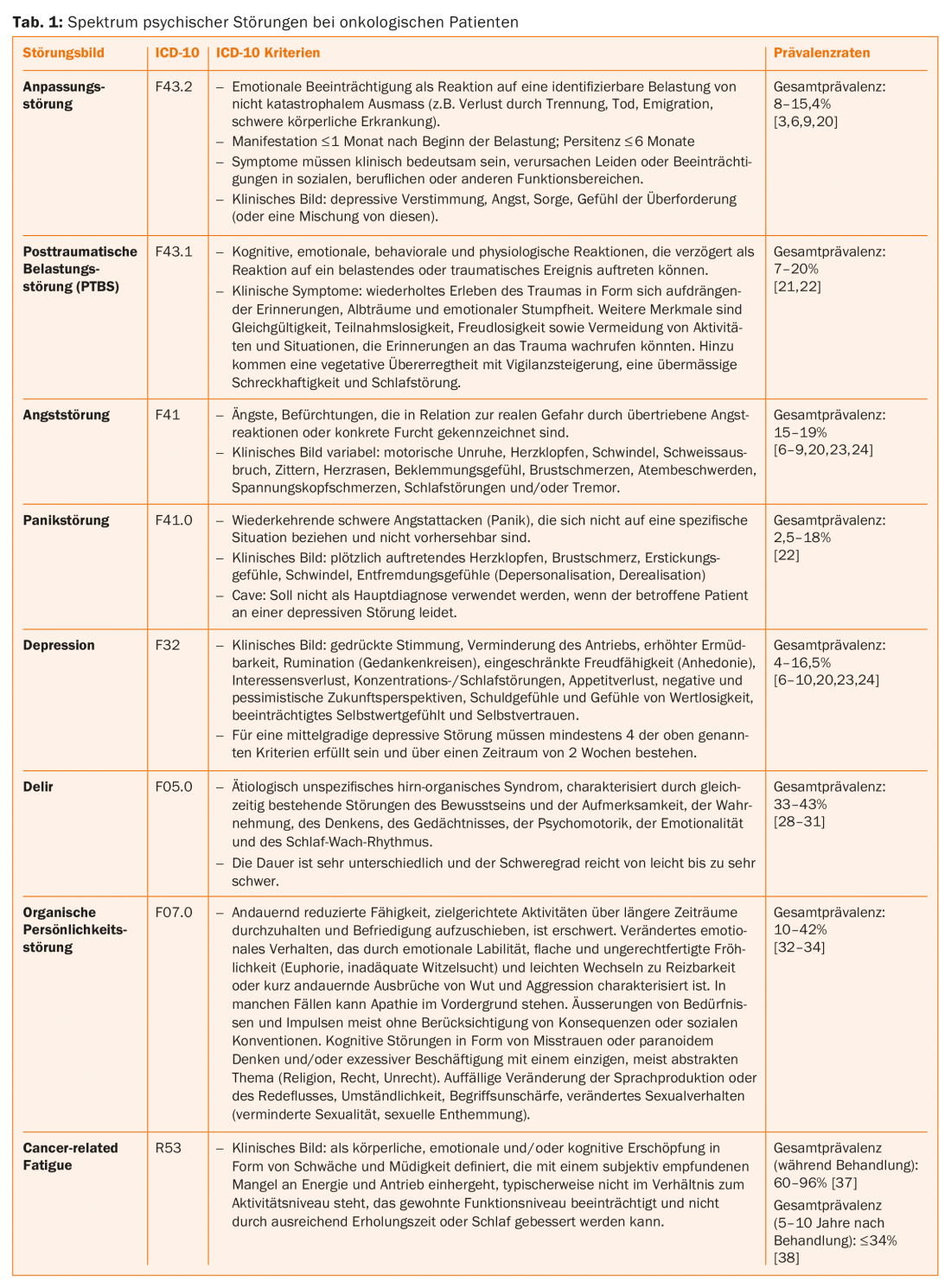

Changes in mental/emotional well-being can also be diagnosed as a mental disorder in the sense of psychiatric comorbidity, depending on the type, degree of severity and duration. Just like early recognition of the need for psycho-oncological treatment, accurate differential diagnostic clarification and differentiation between a normal stress reaction and a mental disorder is of central importance so that specialist support can be initiated in good time and possible chronification can be counteracted. The diagnosis of mental disorders in oncology patients is performed in the consultation/liaison setting according to ICD-10 or DSM-V criteria. Table 1 illustrates the ICD-10 criteria for the most common comorbidities in oncology patients. In addition, there are nowadays a large number of valid and standardized instruments for assessing the severity of mental impairment. In the clinical setting, the Distress Thermometer [15] is often used to assess psychological distress and theHospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [16] is often used to diagnose a patient’s anxiety or depressive disorder.

The most frequent psychological comorbidities in tumor patients

Adjustment disorder (ICD-10: F43.2): Both ICD-10 [17] and DSM-5 [18] define adjustment disorder as an emotional impairment resulting from an identifiable stress of noncatastrophic magnitude (e.g., loss due to separation, death, emigration, severe physical illness) within one (ICD-10) or three (DSM-V) months of the onset of the stress. Symptoms of adjustment disorder resemble those of affective (brief or prolonged depressive reaction), neurotic (anxiety, worry, tension), stress, or somatoform disorders, and social behavior disorders, but never meet the full picture of these diagnostic criteria and must occur within 1 month of exposure and persist for no longer than 6 months, except in the case of prolonged depressive reaction, which may persist for up to 2 years after exposure. Symptoms must be clinically significant in that they cause marked distress or lead to impairment in occupational, social, or other areas of functioning but cannot be explained in the context of simple grief [19]. Prevalence rates of adjustment disorders in oncology patients range from 8 to 15.4% [3,6,9,20].

Post-traumatic stress disorder (ICD-10: F43.1): Patients may react to a diagnosis of cancer, disease progression, medical complications, stem cell transplantation, or treatment in an intensive care unit with a stress response. This is characterized by emotional states such as shock, numbness and denial, despair and hopelessness. As a result, depressive or anxious symptoms may manifest. Scientific research indicates that a cancer diagnosis can also trigger symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). PTSD is defined by ICD-10 criteria as a clinical disorder that includes cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and physiological responses that may occur in a delayed fashion in response to a stressful or traumatic event. Clinical symptoms are the repeated experience of trauma in the form of imposing memories, dreams, or nightmares that occur against a backdrop of a persistent sense of numbness and emotional dullness. Other characteristics include indifference, apathy, joylessness, and avoidance of activities and situations that might evoke memories of the trauma. In addition, there is vegetative overexcitability with an increase in vigilance, excessive startle response and sleep disturbance. Anxiety and depression are often associated with the above symptoms and features. Empirical data on PTSD in oncology patients are conflicting. Prevalence rates vary widely depending on the investigational tools used, ranging from 7.3 to 20% [21,22].

Anxiety disorder (ICD-10: F41): According to the ICD-10 criteria, anxiety disorders are mental disorders characterized by exaggerated fear reactions or concrete fear in relation to real danger. In contrast to pathological fears, fears in tumor patients are to be regarded as a reaction to a real danger in the sense of an existential threat or uncertainty about the further course of the disease. Thus, anxiety in tumor patients occurs particularly in response to pain, loss of control and autonomy, violation of physical integrity, or disease progression (progression anxiety). Physical symptoms of anxiety disorders include motor restlessness, palpitations, dizziness, sweating, tremors, palpitations, chest pain, difficulty breathing, tension headaches, sleep disturbances, and/or tremors. In psycho-oncological treatment, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder and phobic anxiety are the most common. Data on the prevalence rate of anxiety disorders in oncology patients range from 15% to 19% [6–9,20,23,24].

Depressive disorders (ICD-10: F32, 33): Sadness and dejection in response to a cancer diagnosis are adequate and normal human reactions. Symptoms, as distinguished from depression, are transient, less severe, and fluctuate over the course of a day or from one day to the next. Clinical depression, on the other hand, is defined according to ICD-10 criteria by the presence of the following core symptoms: depressed mood, decreased drive, increased fatigability, rumination (thought circling), limited capacity for joy (anhedonia), loss of interest, difficulty concentrating/sleeping, and loss of appetite. In addition, there are negative and pessimistic prospects for the future, feelings of guilt and feelings of worthlessness. In addition, self-esteem and self-confidence are almost always impaired. For moderate depressive disorder, at least four of the above criteria must be met and persist over a period of 2 weeks [10]. Prevalence rates reported for depressive disorders in oncology patients vary widely from 4 to 16.5%, with cancers such as lung cancer, breast cancer, head and neck tumors, and gastrointestinal tumors [6–10,20,23,24] associated with increased risk of depression. In addition, depression in tumor patients is associated with a twofold increased risk of suicide compared with the general population, with a particularly high risk of suicide in the first six months after diagnosis and in patients with advanced tumor disease and poor prognosis [25]. Suicidal thoughts or fantasies in oncologic patients with advanced disease are common in the sense of a way to maintain control (resolution to end suffering) or a cry for help (“I can’t face reality anymore”). Suicidality is a serious complication in the treatment of tumor patients and should be addressed in the following scheme for valid assessment and evaluation: 1) Survey of suicidal intentions, ideas, thoughts, and plans; 2) Survey of risk and protective factors, including past suicidal acts; 3) Determination of necessary target interventions. Nature of suicidal ideation, suicide plans [26]. In addition, psychopharmacological and psychological support is needed in dealing with the disease situation. As the results of a study show, the desire to die decreases in most cases when patients can tell about their distress, are listened to and shown understanding [27].

Delir (ICD-10: F05): According to the ICD-10, delirium is defined as an etiologically non-specific, brain-organic syndrome and is characterized by simultaneously existing disturbance of consciousness, attention, perception, thinking, memory, psychomotor activity, emotionality and sleep-wake rhythm. Delirium has an acute onset temporally related to physical illness, a fluctuating course, and an underlying etiology. More detailed classifications according to the ICD-10 are delirium without dementia (ICD-10: F05.0), postoperative delirium of multifactorial etiology (ICD-10: F05.8), and delirium unspecified (ICD-10: F05.9). Factors that can trigger delirium in oncology patients include sedatives, narcotics, anticholinergics, infections, fever, anemia, electrolyte imbalances, and surgical procedures. Advanced age (> 65 years), dementia, and advanced cancer are significant risk factors for the development of delirium. The prevalence of delirium in oncology patients in the hospital setting varies from 12% to 45% depending on the sample size, patient group, and testing instruments used [28–31].

Organic personality or behavior disorders (ICD-10: F07.0): Organic personality or behavior disorders due to disease, damage, or dysfunction of the brain are characterized by a change in premorbid behavior patterns and involve the expression of affects, impulses, and needs; cognitive abilities such as attention and memory; and sexual behavior. This disorder is also known as frontal brain syndrome, which often occurs in patients with conditions that affect the frontal lobes, such as brain tumors. Data on prevalence rates of organic personality disorders in patients with brain tumors vary from 10% to 42% [32–34].

Cancer-related Fatigue (ICD-10: R53): According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines. [35]), the Cancer-related Fatigue (CrF) defined as a “persistent (persistent) physical, emotional, and/or cognitive fatigue in the form of weakness and fatigue that is accompanied by a subjectively perceived lack of energy and drive, is typically out of proportion to activity levels, interferes with usual levels of functioning, and cannot be improved by adequate recovery time or sleep.” The effects of fatigue symptomatology are complex and can involve physical, cognitive, and affective aspects. Patients report feelings of fatigue and lack of energy, greatly reduced physical performance, increased sensation of pain, impaired memory and concentration, and even a lack of drive and interest. Many of the affected patients often suffer from psychological disorders such as anxiety or depressive mood [36]. These complaints can significantly impair the quality of life and also have devastating consequences with inadequate coping with everyday life, social withdrawal and even occupational and professional disability with financial burdens. Prevalence rates for CrF are high, affecting approximately 60-96% [37] of oncology patients during treatment and approximately 34% of patients 5-10 years after treatment ends [38].

Treatment options

In addition to timely recognition of psychiatric symptomatology requiring treatment, adequate initiation of therapy is important. Moreover, re-evaluation during the course of therapy and, if necessary, adjustment of therapy will be necessary. Treatment of an anxiety disorder or a moderate-to-severe depressive episode in the clinical setting ideally involves combined psychopharmacologic and psycho-oncologic supportive therapy. In general, the treatment offered should be low-threshold and possible on a selective basis and according to individual needs. Treatment services should also be directed at family members.

Psychopharmacological therapy

The use of psychopharmacological therapy for anxiety and depression is recommended depending on the severity, duration and type of symptomatology. In the treatment of moderate to severe depressive disorders, antidepressants from the group of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), especially citalopram or sertraline, are often used to increase drive and elevate mood, or tetracyclic antidepressants such as mirtazapine are used to stabilize mood, regulate sleep, and/or optimize appetite. For anxiolysis or treatment of panic attacks in the clinical setting, it is recommended to use benzodiazepines (e.g., lorazepam) for symptomatic short-term treatment. Lorazepam has a potent and rapid onset of action with a half-life of 12-16 hours. It has antianxiety, sedative, anticonvulsant, and sleep-promoting effects, but should only be used for short periods of time because of the significant potential for dependence. Side effects include sedation, drowsiness, confusion, drowsiness, mental or behavioral disturbances [39].

The management of delirium in the clinical setting is guided by standardized procedures for the prevention, early detection, and treatment of delirium, as well as the use of standardized and validated assessment tools for delirium (e.g., The Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist [ICDSC] [40]). Symptomatic drug therapy for delirium includes reduction of delirium-inducing factors in combination with typical (haloperidol, pipamperone) or atypical neuroleptics, such as olanzapine, quetiapine, or risperidone. Altered QT time has been documented, so these drugs should be administered only under ECG monitoring. In addition, specific non-drug measures should be used to minimize delirium-triggering factors, e.g., by regulating the sleep-wake rhythm, sufficient fluid intake, mobilization, installation of orientation aids, wearing glasses and hearing aids, and avoiding pain [41].

Organic personality disorder (frontal brain syndrome) is best treated with combined pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy (antidepressants in cases of markedly impulsive, apathetic clinical pictures or low-potency neuroleptics in cases of distant-aggressive manifestations) [42].

When psychopharmacological therapy is indicated, individual benefits must be carefully weighed and evaluated against potential side effects (dizziness, lightheadedness, fatigue, nausea, loss of libido) and interactions with tumor therapy. Especially tricyclic antidepressants, some SSRIs (paroxetine, fluoxetine, flufoxamine) as well as St. John’s wort (Hypericum) have inhibitory effects on the cytochrome system (including CYP2D6) and can cause, for example, a reduction in tamoxifen levels [43]. Further, it must be noted that virtually all SSRIs and atypical neuroleptics potentiate the QTc-prolonging effects of many oncologic drugs [44]. When recommending psychotropic drugs, the principle is that the fewer possible interactions, the better.

Psychotherapy

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is considered an effective therapeutic method in the treatment of anxiety or depressive disorders in patients with oncological diseases [45]. CBT is directed at changing dysfunctional cognitions and behaviors that influence or exacerbate depressive symptomatology. In addition to acute treatment of depressive disorders, CBT identifies maladaptive coping strategies, strengthens individual resources, offers support in coping with anxiety (fear of progression), physical changes, and acceptance of the illness, and identifies opportunities for changing life perspectives.

In psycho-oncology, psychotherapeutic approaches to finding meaning and enhancing dignity and self-determination have become established in recent years, in addition to CBT. The Individual or Group Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy (IMCP) according to Breitbart [46,47] is a method based on the logotherapy of Viktor Frankl. [48] based therapy that uses weekly therapy sessions to address issues such as individual concepts and sources of meaning and meaningfulness, significant individual life concepts and aspects of personal life history, responsibility, creativity, and individual roles in family, work, and society, as well as issues of farewell, endings, and hope for one’s future. IMCP has been scientifically shown to significantly improve spiritual well-being and quality of life, but not anxiety, depression, or hopelessness, in patients with advanced oncologic disease.

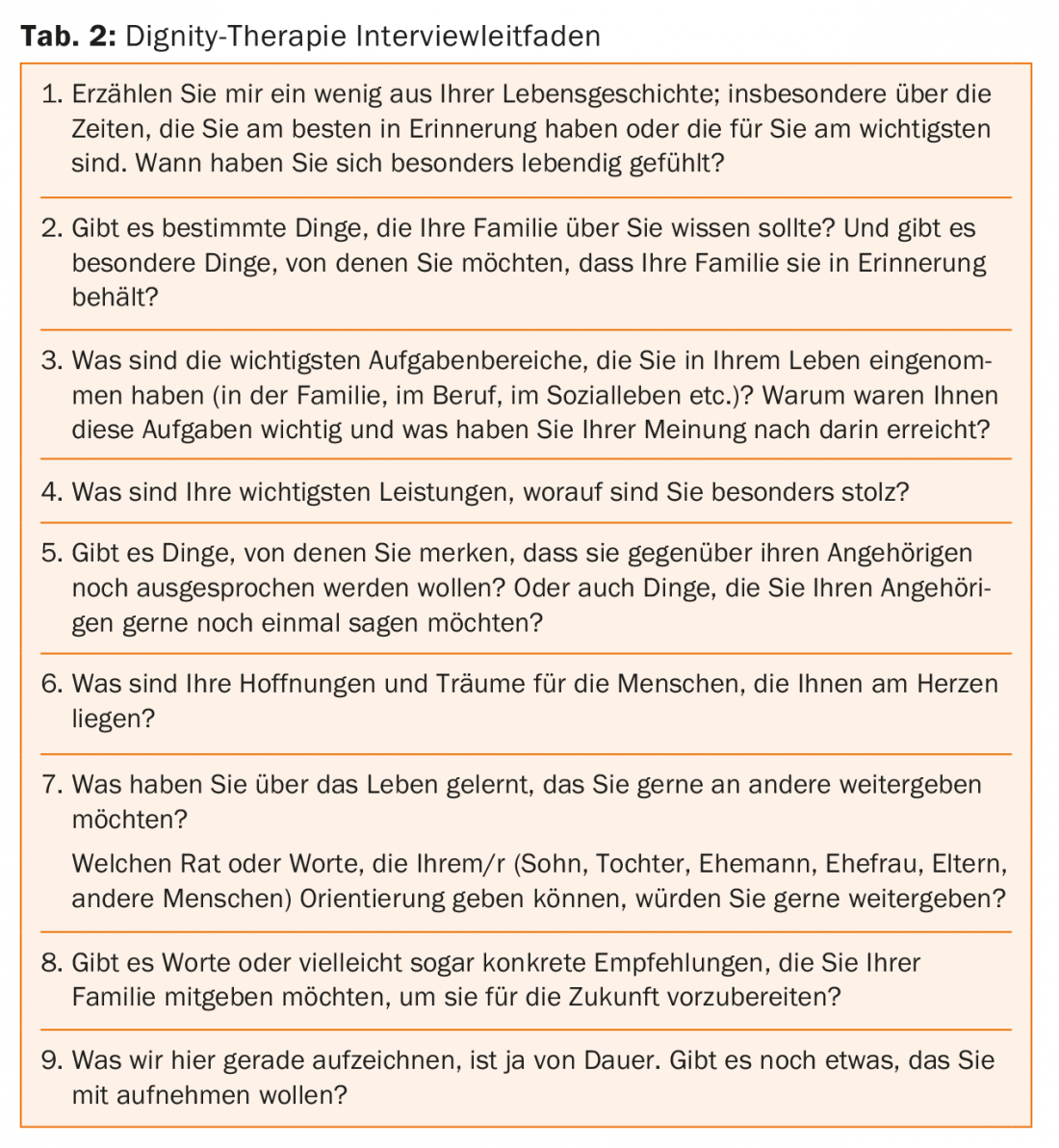

Dignity Therapy (Dignity-Centered Therapy) by Harvey Chochinov [49] is a short-term intervention to enhance individual dignity and self-determination in patients with advanced oncologic disease. The therapy was developed on the assumption that severe advanced oncological disease is associated with a substantial loss of dignity, and that this in turn can trigger a desire in affected patients to die prematurely. By asking specific questions and writing down the patient’s memories, wishes and concerns, the aim is to increase the patient’s appreciation of his or her own life, to help him or her find meaning, and to recognize or reinforce the importance of his or her own life’s work. This narrative is guided by an interview guide (Tab. 2), the interview is recorded, transcribed, discussed with the patient, edited and finally given to the patient as a written document (generativity document). Dignity Therapy demonstrated significant improvement in quality of life and self-determination in patients with advanced oncologic disease, resulting in an enhanced sense of dignity. In addition, family members also reported finding Dignity Therapy helpful.

Psychooncology offers many other psychotherapeutic methods with scientific evidence in the treatment of anxiety, depressive disorders, pain and sleep disorders in oncology patients, including Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) [50–52], relaxation and imaginative methods (Mindfulness-based Therapy) [53], body therapy (acupuncture, respiratory therapy, shiatsu, qi gong, etc.) [54] or music and art therapy [55].

Literature:

- Federal Statistical Office (FSO), Swiss Cancer Report 2015. Status and development, 2015.

- Guidelines program on oncology (German Cancer Society, German Cancer Aid, AWMF) Psychooncological diagnosis, counseling and treatment of adult cancer patients, 2014.

- Hund B., Reuter K., Harter M., Brahler E., Faller H., Keller M., Schulz H., Wegscheider K., Weis J., Wittchen H. U., Koch U., Friedrich M., Mehnert A., Stressors, Symptom Profile, Stressors, symptom profile, and predictors of adjustment disorder in cancer patients. Results from an epidemiological study with the composite international diagnostic interview, adaptation for oncology (cidi-o). Depressed Anxiety, 2016. 33(2): p. 153-61.

- Meyer F., Fletcher K., Prigerson H. G., Braun I. M., Maciejewski P. K., Advanced cancer as a risk for major depressive episodes. Psychooncology, 2015. 24(9): p. 1080-7.

- Singer S., Das-Munshi J., Brahler E., Prevalence of mental health conditions in cancer patients in acute care–a meta-analysis. Ann Oncol, 2010. 21(5): p. 925-30.

- Mitchell A. J., Chan M., Bhatti H., Halton M., Grassi L., Johansen C., Meader N., Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol, 2011. 12(2): p. 160-74.

- Linden W., Vodermaier A., Mackenzie R., Greig D., Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord, 2012. 141(2-3): p. 343-51.

- Kuhnt S., Brahler E., Faller H., Harter M., Keller M., Schulz H., Wegscheider K., Weis J., Boehncke A., Hund B., Reuter K., Richard M., Sehner S., Wittchen H. U., Koch U., Mehnert A., Twelve-Month and Lifetime Prevalence of Mental Disorders in Cancer Patients. Psychother Psychosom, 2016. 85(5): p. 289-96.

- Mehnert A., Brahler E., Faller H., Harter M., Keller M., Schulz H., Wegscheider K., Weis J., Boehncke A., Hund B., Reuter K., Richard M., Sehner S., Sommerfeldt S., Szalai C., Wittchen H. U., Koch U., Four-week prevalence of mental disorders in patients with cancer across major tumor entities. J Clin Oncol, 2014. 32(31): p. 3540-6.

- Walker J., Hansen C. H., Martin P., Symeonides S., Ramessur R., Murray G., Sharpe M., Prevalence, associations, and adequacy of treatment of major depression in patients with cancer: a cross-sectional analysis of routinely collected clinical data. Lancet Psychiatry, 2014. 1(5): p. 343-50.

- Lu D., Andersson T. M., Fall K., Hultman C. M., Czene K., Valdimarsdottir U., Fang F., Clinical Diagnosis of Mental Disorders Immediately Before and After Cancer Diagnosis: A Nationwide Matched Cohort Study in Sweden. JAMA Oncol, 2016. 2(9): p. 1188-96.

- Sperner-Unterweger B., [Depression in cancer patients]. Wien Med Wochenschr, 2015. 165(15-16): p. 297-303.

- Lutgendorf S. K., Andersen B. L., Biobehavioral approaches to cancer progression and survival: Mechanisms and interventions. Am Psychol, 2015. 70(2): p. 186-97.

- Bortolato B., Hyphantis T. N., Valpione S., Perini G., Maes M., Morris G., Kubera M., Kohler C. A., Fernandes B. S., Stubbs B., Pavlidis N., Carvalho A. F., Depression in cancer: the many biobehavioral pathways driving tumor progression. Cancer Treat Rev, 2017. 52: p. 58-70.

- Mehnert A., Müller D., Lehmann C., Koch U., The German version of the NCCN Distress Thermometer. Empirical testing of a screening instrument to assess psychosocial distress in cancer patients. Journal of Psychiatry, Psychology and Psychotherapy, 2006. 54(3): p. 213-223.

- Zigmond A. S., Snaith R. P., The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 1983. 67(6): p. 361-70.

- World Health Oragnization, The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders. Vol. 10. 1992, Geneva: Author.

- American Psychiatric Associaion, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 2013, Washington, DC: Author.

- Lorenz Louisa, Diagnosing Adjustment Disorders: A questionnaire on the new ICD-11 model. 2016, Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

- Hernandez Blazquez M., Cruzado J. A., A longitudinal study on anxiety, depressive and adjustment disorder, suicide ideation and symptoms of emotional distress in patients with cancer undergoing radiotherapy. J Psychosom Res, 2016. 87: p. 14-21.

- Cordova M. J., Riba M. B., Spiegel D., Post-traumatic stress disorder and cancer. Lancet Psychiatry, 2017.

- Abbey G., Thompson S. B., Hickish T., Heathcote D., A meta-analysis of prevalence rates and moderating factors for cancer-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychooncology, 2015. 24(4): p. 371-81.

- Brintzenhofe-Szoc K. M., Levin T. T., Li Y., Kissane D. W., Zabora J. R., Mixed anxiety/depression symptoms in a large cancer cohort: prevalence by cancer type. Psychosomatics, 2009. 50(4): p. 383-91.

- Rasic D. T., Belik S. L., Bolton J. M., Chochinov H. M., Sareen J., Cancer, mental disorders, suicidal ideation and attempts in a large community sample. Psychooncology, 2008. 17(7): p. 660-7.

- Oberaigner W., Sperner-Unterweger B., Fiegl M., Geiger-Gritsch S., Haring C., Increased suicide risk in cancer patients in Tyrol/Austria. Gen Hosp Psychiatry, 2014. 36(5): p. 483-7.

- Morriss R., Kapur N., Byng R., Assessing risk of suicide or self harm in adults. Bmj, 2013. 347: p. f4572.

- Monforte-Royo C., Villavicencio-Chavez C., Tomas-Sabado J., Mahtani-Chugani V., Balaguer A., What lies behind the wish to hasten death? A systematic review and meta-ethnography from the perspective of patients. PLoS One, 2012. 7(5): p. e37117.

- Grandahl M. G., Nielsen S. E., Koerner E. A., Schultz H. H., Arnfred S. M., Prevalence of delirium among patients at a cancer ward: clinical risk factors and prediction by bedside cognitive tests. North J Psychiatry, 2016. 70(6): p. 413-7.

- Uchida M., Okuyama T., Ito Y., Nakaguchi T., Miyazaki M., Sakamoto M., Kamiya T., Sato S., Takeyama H., Joh T., Meagher D., Akechi T., Prevalence, course and factors associated with delirium in elderly patients with advanced cancer: a longitudinal observational study. Jpn J Clin Oncol, 2015. 45(10): p. 934-40.

- Van Der Vorst M., Verdegaal B., Beekman A. T., Berkhof J., Verheul H. M., Identification of patients at risk for delirium on a medical oncology hospital ward. J Clin Oncol, 2014. 32(31_suppl): p. 130.

- Hempenius L., Slaets J. P., van Asselt D., de Bock T. H., Wiggers T., van Leeuwen B. L., Long-term outcomes of a geriatric liaison intervention in frail elderly cancer patients. PLoS One, 2016. 11(2): p. e0143364.

- Boele F. W., Rooney A. G., Grant R., Klein M., Psychiatric symptoms in glioma patients: from diagnosis to management. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat, 2015. 11: p. 1413-20.

- Madhusoodanan S., Ting M. B., Farah T., Ugur U., Psychiatric aspects of brain tumors: A review. World J Psychiatry, 2015. 5(3): p. 273-85.

- Jenkins L. M., Drummond K. J., Andrewes D. G., Emotional and personality changes following brain tumor resection. J Clin Neurosci, 2016. 29: p. 128-32.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Cancer-Related Fatigue. Version 1, 2016.

- Bower J. E., Ganz P. A., Irwin M. R., Kwan L., Breen E. C., Cole S. W., Inflammation and behavioral symptoms after breast cancer treatment: do fatigue, depression, and sleep disturbance share a common underlying mechanism? J Clin Oncol, 2011. 29(26): p. 3517-22.

- Abrahams H. J., Gielissen M. F., Schmits I. C., Verhagen C. A., Rovers M. M., Knoop H., Risk factors, prevalence, and course of severe fatigue after breast cancer treatment: a meta-analysis involving 12 327 breast cancer survivors. Ann Oncol, 2016. 27(6): p. 965-74.

- Bower J. E., Ganz P. A., Desmond K. A., Bernaards C., Rowland J. H., Meyerowitz B. E., Belin T. R., Fatigue in long-term breast carcinoma survivors: a longitudinal investigation. Cancer, 2006. 106(4): p. 751-8.

- Ameer B., Greenblatt D. J., Lorazepam: a review of its clinical pharmacological properties and therapeutic uses. Drugs, 1981. 21(3): p. 162-200.

- Bergeron N., Dubois M. J., Dumont M., Dial S., Skrobik Y., Intensive care delirium screening checklist: evaluation of a new screening tool. Intensive Care Med, 2001. 27(5): p. 859-64.

- Schubert M. , Massarotto P., Wehrli M., Lehmann A., Spirig R., Hasemann W. Vol. 18. 2010, Stuttgart – New York: Georg Thieme Verlag KG. 316-323.

- Gleixner Ch., Müller M.J., Wirth S., Neurology and Psychiatry. For study and practice. 11th ed. 2017, Breisach: Medical Publishing and Information Services.

- Chang M., Tybring G., Dahl M. L., Lindh J. D., Impact of cytochrome P450 2C19 polymorphisms on citalopram/escitalopram exposure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Pharmacokinet, 2014. 53(9): p. 801-11.

- van Noord C., Straus S. M., Sturkenboom M. C., Hofman A., Aarnoudse A. J., Bagnardi V., Kors J. A., Newton-Cheh C., Witteman J. C., Stricker B. H., Psychotropic drugs associated with corrected QT interval prolongation. J Clin Psychopharmacol, 2009. 29(1): p. 9-15.

- Hart S. L., Hoyt M. A., Diefenbach M., Anderson D. R., Kilbourn K. M., Craft L. L., Steel J. L., Cuijpers P., Mohr D. C., Berendsen M., Spring B., Stanton A. L., Meta-analysis of efficacy of interventions for elevated depressive symptoms in adults diagnosed with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2012. 104(13): p. 990-1004.

- Breitbart W., Poppito S., Rosenfeld B., Vickers A. J., Li Y., Abbey J., Olden M., Pessin H., Lichtenthal W., Sjoberg D., Cassileth B. R., Pilot randomized controlled trial of individual meaning-centered psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol, 2012. 30(12): p. 1304-9.

- Breitbart W., Rosenfeld B., Gibson C., Pessin H., Poppito S., Nelson C., Tomarken A., Timm A. K., Berg A., Jacobson C., Sorger B., Abbey J., Olden M., Meaning-centered group psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology, 2010. 19(1): p. 21-8.

- Frankl Viktor, E., Logotherapy and Existential Analysis: Texts from Six Decades . 1998, Weinheim and Basel: Beltz Taschenbuch.

- Chochinov H. M., Kristjanson L. J., Breitbart W., McClement S., Hack T. F., Hassard T., Harlos M., The effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol, 2011. 12(8): p. 753-62.

- Hayes S. C., Luoma J. B., Bond F. W., Masuda A., Lillis J., Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther, 2006. 44(1): p. 1-25.

- Kangas M., McDonald S., Williams J. R., Smee R. I., Acceptance and commitment therapy program for distressed adults with a primary brain tumor: a case series study. Support Care Cancer, 2015. 23(10): p. 2855-9.

- Feros D. L., Lane L., Ciarrochi J., Blackledge J. T., Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for improving the lives of cancer patients: a preliminary study. Psychooncology, 2013. 22(2): p. 459-64.

- Zhang M. F., Wen Y. S., Liu W. Y., Peng L. F., Wu X. D., Liu Q. W., Effectiveness of Mindfulness-based Therapy for Reducing Anxiety and Depression in Patients With Cancer: A Meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore), 2015. 94(45): p. e0897-0.

- Tao W. W., Jiang H., Tao X. M., Jiang P., Sha L. Y., Sun X. C., Effects of Acupuncture, Tuina, Tai Chi, Qigong, and Traditional Chinese Medicine Five-Element Music Therapy on Symptom Management and Quality of Life for Cancer Patients: A Meta-Analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage, 2016. 51(4): p. 728-47.

- Arruda M. A., Garcia M. A., Garcia J. B., Evaluation of the Effects of Music and Poetry in Oncologic Pain Relief: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Palliat Med, 2016. 19(9): p. 943-8.

- Seiler A., Büel-Drabe N., Jenewein J., Treatment of tumor-associated fatigue in breast cancer. Praxis, 2017. 106(135-142).

- Seiler A., Jenewein J., Depressive disorders in patients with oncological diseases. Info@oncology 7-2016

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2017; 15(2): 4-12.