Most depressed patients first seek help from their primary care physician. During the consultation, the focus is often not on mood states but on somatic disorders and complaints. Treatment planning depends primarily on the severity of the depression: mild depression can initially be observed with mindful guidance, while more severe depression should be treated with antidepressants as well as psychotherapeutic procedures.

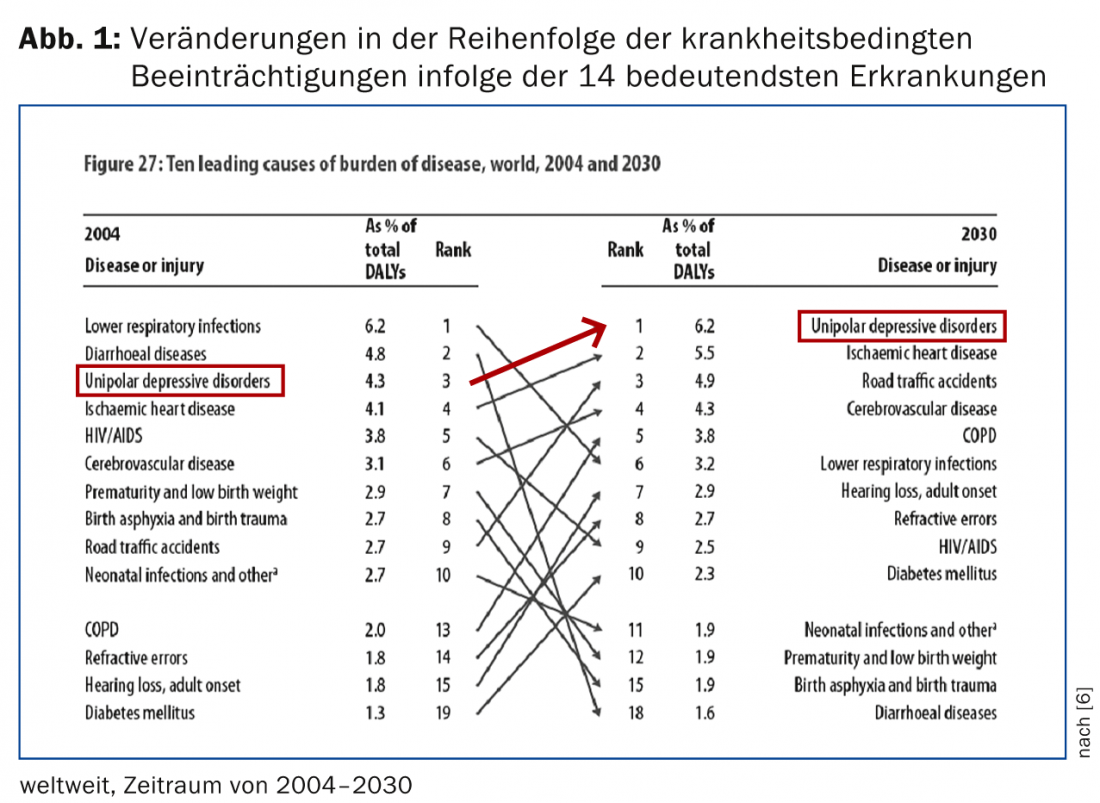

Depression is one of the most common psychiatric disorders in modern society. According to WHO estimates, by 2020 depression will rank second, directly after cardiovascular disease, in the order of diseases that are the main cause of years of life lost due to severe disability or death (Fig.1). Lifetime prevalence for depression ranges from 7% to 18% (average prevalence rate approximately 10.4%). Women fall ill twice as often as men. About one in ten patients in primary care practice is believed to suffer from depression, which is not recognized or appropriately treated in nearly half of the cases [1–3]. Family physicians and general practitioners are of particular importance in the diagnosis and treatment of depression.

Multiple symptoms, including somatic symptoms

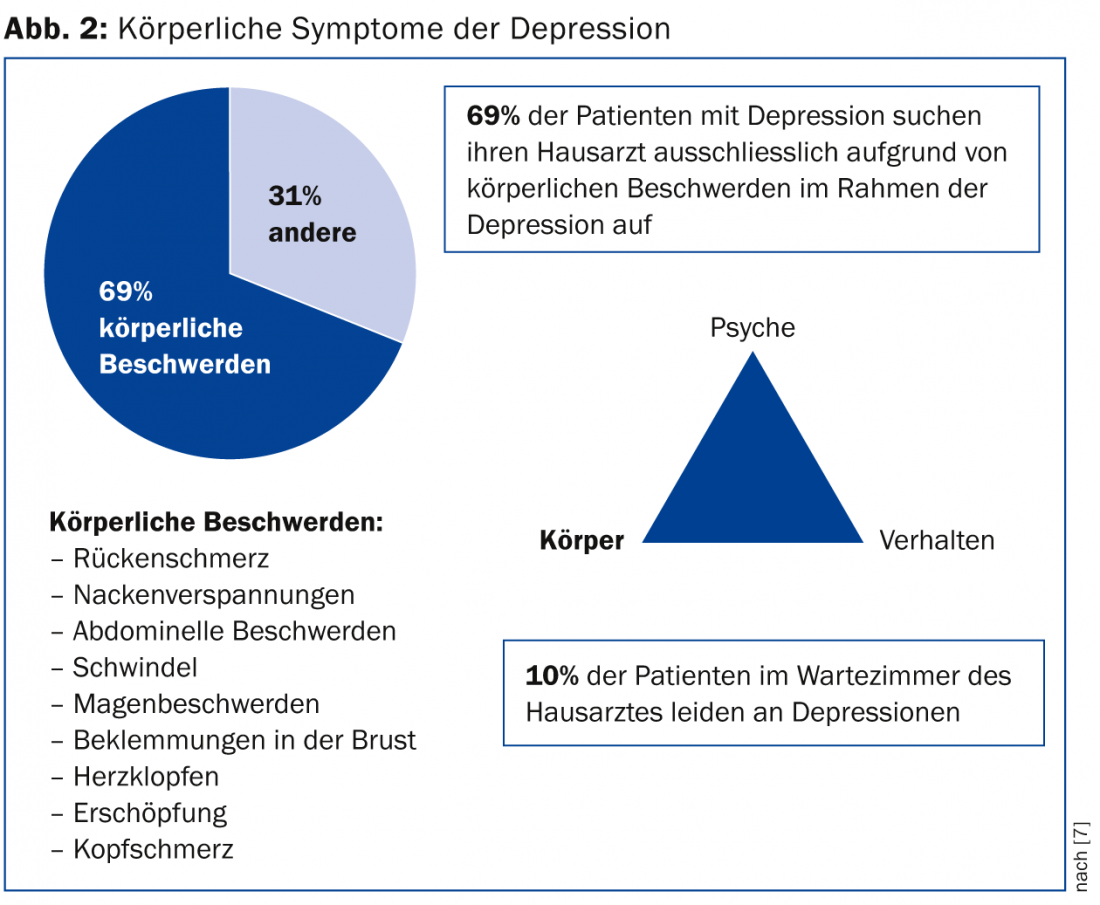

It can be assumed that most depressive patients first seek help from their family doctor. It must also be taken into account that prejudices against psychiatric illnesses still exist in the population. These are linked to inhibitions and feelings of shame, which contribute to the fact that depressive mood states are often not addressed directly by the affected person, but rather indirectly with reference to the present somatic and vegetative symptoms of depression. (Fig. 2). In the case of depressive patients, it is not only their state of mind that is disturbed; drive, cognitive and biological functions are also impaired.

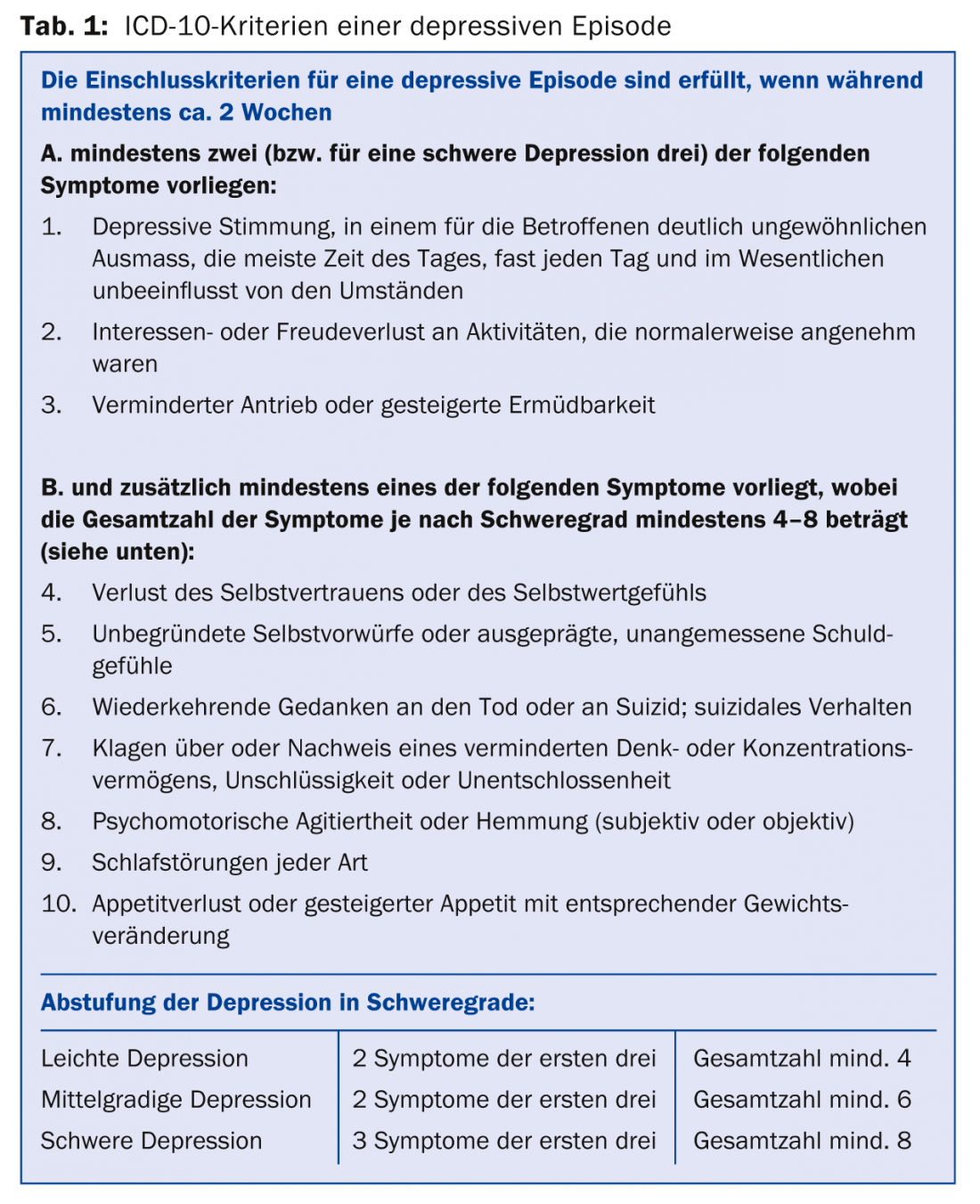

Accordingly, the leading symptoms of depression include depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure (anhedonia), and decreased drive ( table 1).

Triggers and comorbidities

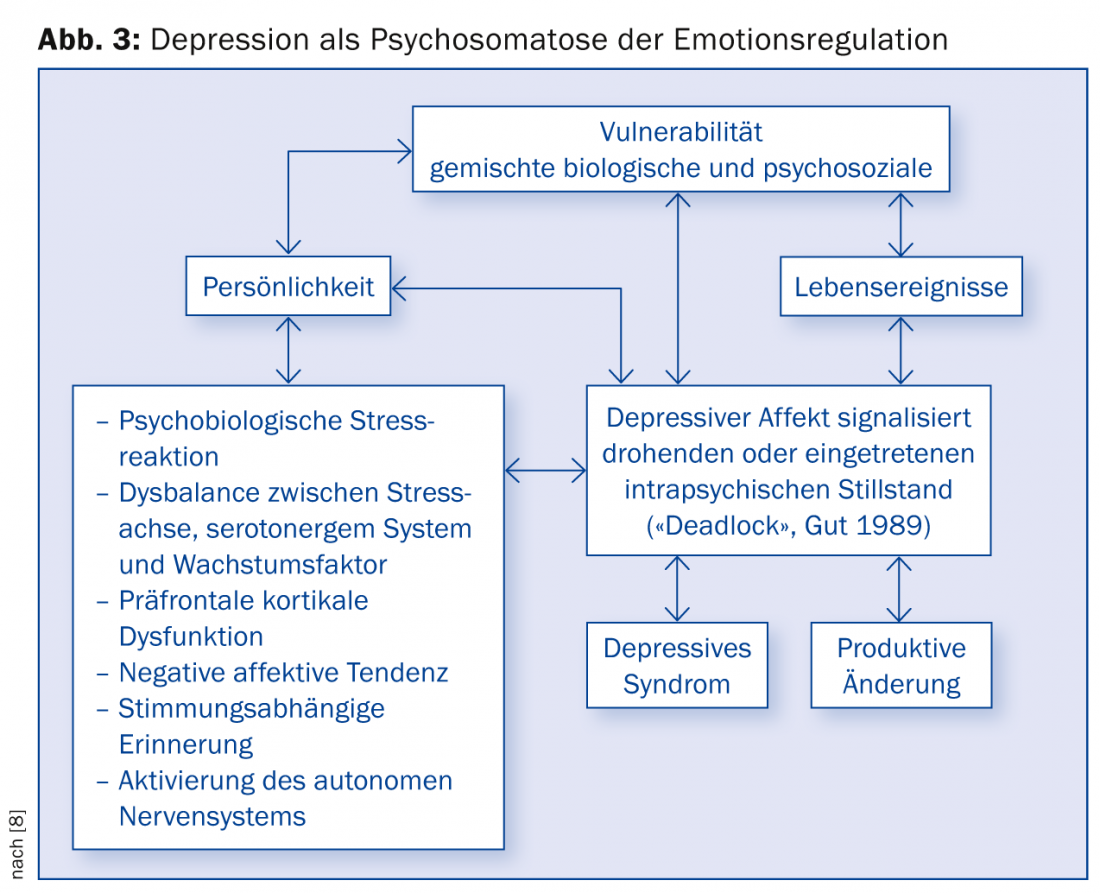

Depression is often triggered by a specific internal or external stress situation that, depending on genetic or biographically determined vulnerability, leads to excessive cortisol release and altered brain activity patterns, especially in the rostral and limbic systems. In the context of a person’s self-evaluation and social situation, the basic bio-psycho-social pattern of depression may be reinforced or sustained by a fierce but dysfunctional resistance on the part of the individual. For example, a young woman with young children may fight a still mild depressive inhibition out of family obligation, or a self-critical man with a high work ethic may fight it out of inner conviction. In addition, direct biological influences, which mainly affect the rostral limbic system incl. the brain, are also important. prefrontal cortex should be considered in the development of depression (e.g., frontal cerebrovascular insults, hypothyroidism, steroid or cytostatic therapies, etc.). In view of this multidimensionality of depressive disorders, they can be understood as psychosomatoses of emotion regulation (Fig. 3).

A significant problem also arises in particular from the high comorbidity with other mental (e.g. anxiety disorders, somatization disorder, addictions) and somatic diseases (e.g. coronary heart disease). This variability of symptomatology (agitation, drive inhibition, suicidality, body symptoms, cognitive dysfunction, psychotic symptoms) must be taken into account in the treatment of depression.

Attentive accompaniment of those affected

Treatment planning in the acute stage of the disease is mainly based on the severity of the depression. In the case of mild depressive symptomatology, mindful accompaniment is initially recommended (education and information, active-waiting accompaniment within 14 days) [4]. This should consist of monitoring the progression of symptoms through short-term re-presentations, assessing the patient’s existing coping mechanisms and social support in the family environment.

An essential foundation of depression treatment is the therapeutic attitude of those treating the patient. This enables depressive patients to experience themselves as accepted even in their illness. The opportunity to communicate and to experience a response from the other person represents a first essential healing experience for the depressive sufferer, who has often withdrawn for a long period of time for reasons of shame and often has not included close relatives. The existing complaints should be asked as openly and soberly as possible. It may be essential to address the possibility of suicidality. With relativizations of the complaints and false comforts (“half as bad”, “will be all right”), doctors can – without wanting to – contribute to a further increase in the already existing tendencies of depressive patients to overtax themselves and/or to experience themselves as failures.

If symptoms persist or worsen, the initiation of psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy should be considered after about two to four weeks, even in the case of mild depression. Interventions should take into account that empathetic understanding of depressed people is complicated by the fact that they are less able to resonate affectively and also often appear as dysphorically disgruntled, so that negative reactions may develop on the part of the clinician. This is a not infrequently occurring interaction phenomenon with a depressed person. It is of great consequence in the further course if this interaction phenomenon triggered by the depressive patient leads to withdrawal or even therapeutic nihilism. It is advisable to initially summarize complaints and grievances without comment, but not to interpret or even relativize them.

Diagnostic and therapeutic interview

At this point it becomes apparent that the diagnostic interview is already the beginning of the therapy. In practice, it proves useful to start with physical symptoms (sleep disturbances, loss of appetite and weight, impulse disorders, loss of concentration and memory, morning lows and daily rhythms) and only gradually address the inner experience that is difficult to put into words (fears of failure and the future, self-reproaches, delusions of guilt). It should also be taken into account that the overall time experience of depressive patients is slowed down. If the necessary time is lacking during an initial consultation, patients should be called back in as soon as possible. It is always important to assess acute suicidality before continuing outpatient therapy.

Communicating the diagnosis and other diagnostic information often has a relieving function for patients, as it makes it clear that they have a known medical condition with a favorable prognosis. Any necessary sick leave can counteract the compensatory self-overload of depressive patients. Rarely, hospitalization will be necessary, especially for acute suicidality and major depressive episodes. The relieving therapeutic effect may be further enhanced by temporarily removing the depressed patient from his or her environment of daily and domestic duties. However, longer vacation trips or stays at a health resort are not advisable. These are usually experienced as a burden by depressive patients, who feel overwhelmed by the expectations placed on them.

Involve relatives

If there are signs that relatives are reacting helplessly, feeling guilty, reacting impatiently-demandingly or critically-rejecting, the partner should also be consulted with the consent of the depressive and informed about the diagnosis. Patience is sometimes easier to muster on the part of all those affected if they can be realistically given hope – based on a good prognosis of the depressive condition. In premorbidly strained relationships, it may be helpful to support the partner in one-on-one sessions and offer couples or family discussions later, when the depression has subsided.

Principles of pharmacotherapy

Psychopharmacotherapeutic treatment is usually indicated for moderate and severe depression. Among psychotropic drugs, traditional antidepressants (especially tricyclics) are associated with more side effects – mainly vegetative and cardiovascular – than modern selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), selective MAO inhibitors (MAO-I), and selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSNRIs) [5]. A new drug treatment strategy is agomelatine, which at the same time positively affects sleep regulation and does not trigger sexual side effects.

At this stage, it can be assumed that all antidepressants on the market differ less in their efficacy and more in their undesirable side effects. The so-called second- and third-generation antidepressants, in contrast to the tricyclic, tetracyclic, and atypical antidepressants, cause fewer clinically relevant side effects and are thus suitable for treatment in the outpatient setting, in cases of comorbidity, or in old age. However, the use of tricyclic, tetracyclic and atypical antidepressants cannot be dispensed with in everyday clinical practice – even under outpatient conditions. Taking precautions into account (e.g., ECG checks with regard to cardiovascular side effects), tricyclics should be resorted to, especially in cases of severe depression, and the use of so-called “tricyclics” should also be considered. irreversible MAO inhibitors should be considered.

Antidepressant should take effect after 10-14 days

As a principle, any treatment attempt should be made with sufficient high doses and sufficiently long duration if tolerability is acceptable. The success rate for initial thymoleptic treatment is approximately 65% for mild depression and approximately 50% for severe depression. It is important to inform patients of these relationships to prevent depressive-resignative processing of a potentially failing initial drug treatment attempt.

The goal of acute treatment is to find an effective medication as quickly as possible to achieve improvement and ultimately freedom from symptoms. In contrast to the earlier assumptions of a large effect latency, it is now assumed that an antidepressant should show a desired efficacy after about 10-14 days. If this is not the case, the dose should be increased. Under no circumstances should antidepressants be used for a long period of time with an unchanged therapeutic strategy in the absence of efficacy. Augmentation strategies should be considered, i.e., the use of lithium or other mood stabilizers such as antiepileptic drugs, furthermore also thyrostatic drugs.

During the stabilization phase, which lasts approximately six months, dosing should be continued at approximately the same dose. Subsequent dose reduction should be done carefully in small steps.

In principle, any drug treatment must include a good assessment of suicidality and the ability to seek help in a crisis. Medications with a narrow therapeutic range or high toxicity in intoxication (e.g., lithium, TCA) should either be avoided during acute treatment if in doubt, or a suitable delivery modality should be sought.

Practical recommendations for antidepressant selection.

When choosing an antidepressant, the following recommendations may be helpful:

- If a patient has previously responded well to a particular antidepressant, a trial of that medication is recommended. An exception is made for new contraindications that have arisen in the meantime, such as cardiac arrhythmias, etc.

- In cases of pronounced sleep disturbances, a sedating antidepressant (possibly also in a single dose, e.g., mianserin, trazodone) may be given in the evening. If sleep disturbances persist nevertheless, the temporary administration of a longer-acting benzodiazepine preparation is helpful (e.g., flurazepam). In cases of pronounced anxiety or suicidality, a benzodiazepine preparation with a longer half-life is also recommended during the day (e.g., diazepam). Less sedating antidepressants (e.g., paroxetine, citalopram, moclobemide) can also be combined with sedating agents. In the longer term, the dependency problem must be kept in mind. If acute suicidality persists, consider the use of lithium and/or other phase prophylactics (antiepileptic drugs).

- In clinical practice, it has proven useful to select antidepressants also according to their side effect profiles. In outpatient treatment, generally better-tolerated new-generation antidepressants are considered the antidepressants of first choice because of their lack of anticholinergic side effects, especially with regard to compliance (e.g., fitness to drive). This is especially true for the treatment of elderly patients. Patients with cardiac dysfunction, prostatic hypertrophy, glaucoma, and other contraindications to anticholinergic medication should not be treated with tricyclics or maprotiline without intensive monitoring.

- Patients suffering from major depression, especially including depressive delusions (impoverishment, guilt, hypochondriacal, and nihilistic delusions), usually require combination treatment of an antidepressant with a neuroleptic (e.g., quetiapine).

- Depressed patients who also suffer from obsessive-compulsive disorder or bulimia respond particularly well to clomipramine as well as to SSRI preparations. It can be assumed that a specific spectrum of action for antidepressants cannot be definitively established because newly developed drugs in particular provide evidence that they may be effective not only in various subtypes of depressive symptoms but also in generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, phobic disorders, and other mental disorders (e.g., in the context of comorbidity in somatic disorders). Furthermore, atypical neuroleptics (e.g., quetiapine) are increasingly finding their way into depression treatment.

Management of even the newer, better-tolerated antidepressants with concomitant use of other medications can be complicated by interactions. Combinations of moclobemide with clomipramine, SSRIs, and the serotonin precursors L-tryptophan and L-5-hydroxytrypophan are particularly dangerous: there is a risk for a life-threatening serotonin syndrome with, among other things, agitation, myoclonia, confusion, and seizures.

Psychotherapeutic treatment approaches

Supportive and understanding guidance in the sense of basic psychotherapeutic treatment is an essential component of any form of depression treatment. Specific psychotherapeutic methods can be used in cases of improved severe depression or in cases of mild to moderate depression from the beginning. All psychotherapeutic psychotherapy methods that have so far proven their effectiveness in controlled studies attack the same point in one way or another: At the tendency of depressed people to question themselves and to feel helplessly at the mercy of others.

The goal of psychotherapeutic depression treatment is to dissolve the intrapsychic and social vicious circles of depression: Staged activation in the behavioral therapy approach, overcoming dysfunctional thought content in the cognitive-behavioral approach, processing self-esteem doubts, inflated self-expectations, ideal concepts as well as feelings of guilt and inclusion of the biographical background in psychoanalytic psychotherapy, coping with interpersonal conflicts and overcoming pathological grief reactions and personal losses in personal psychotherapy. In cases of long-standing depression that has existed since adolescence and is often chronic, the use of CBASP (“Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy”) should be considered.

Outlook

The general practitioner’s office is often the first and, in many cases, the most important continuous point of contact for many depressive patients during the longer course of treatment. In acute depression, depending on severity (attentive monitoring in mild depression), consider initiating both antidepressant medication and disorder-specific psychotherapeutic interventions. The indication for individual forms of therapy is essentially dependent on the current level of suffering, the motivation and the introspection ability of the patient. The previous course of the disease, personality factors and social conditions must also be taken into account.

Collaboration with psychiatrists is often required for clarification of acute suicidality and with regard to treatment of moderate and severe depression. In patients with recurrent depressive episodes, drug prophylaxis should be continued at the therapeutic dose of the acute dose for even longer. With long-term antidepressant prophylaxis, a somatic check-up (including ECG) is recommended annually, especially in elderly patients. An alternative to long-term treatment with antidepressants is prophylaxis with lithium or the use of other mood stabilizers (antiepileptic drugs, e.g., lamotrigine).

Prof. Dr. med. Heinz Böker

Literature:

- Jacoby I, et al: Retraining physicians for primary care. A study of physicians perspectives and program development. JAMA 1997; 277(19): 1569-1573.

- Üstün TB, Sartorius N (eds): Mental illness in general healthcare. An international study. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, New York, Brisbane, Toronto, Singapore 1995.

- Wittchen HU: The depression 2000 study. A nationwide depression screening study in general practices. Progress in Medicine 2000; 188: special issue i: 1-3.

- DGPPN, BÄK, KBV, AWMF, AkdÄ, BPtK, BApK, DAGSHG, DEGAM, DGPs, DGRW for the guideline group Unipolar Depression (ed.) (2009): S3-Leitlinie/Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Unipolare Depression-Langfassung, 1st edition. Berlin, Düsseldorf (DGPPN, ÄZQ, AWMF). Internet: www.dgppn.de, www.versorgungsleitlinien.de, www.awmf-leitlinien.de.

- Holsboer-Trachsler E, et al: The somatic treatment of unipolar depressive disorders. Parts 1 and 2. (Treatment recommendations of the Swiss Society for Anxiety and Depression). Schweiz Med Forum 2010; 10(46): 802-809.

- The Global Burden of Disease, 2004 Update, WHO.

- Simon GE, et al: An international study of the relation between somatic symptoms and depression. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 1329-1335.

- Böker H: Psychotherapy of depression. Verlag Hans Huber, Hogrefe AG, Bern 2011.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- Depressive mood states are often not addressed directly by those affected, but often indirectly with reference to somatic and vegetative symptoms.

- Treatment planning in the acute stage of the disease is mainly based on the severity of the depression.

- If symptoms persist or worsen, the initiation of psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy should be considered after about two to four weeks, even in the case of mild depression.

- All antidepressants on the market differ less in their efficacy than in their undesirable side effects.

- An antidepressant should show a desired efficacy after about 10-14 days; if not, the dose should be increased.

- All psychotherapeutic psychotherapy methods that have so far proven their effectiveness in controlled studies attack the same point in one way or another: At the tendency of depressed people to question themselves and to feel helplessly at the mercy of others.

- Collaboration with psychiatrists is often required for clarification of acute suicidality and with regard to treatment of moderate and severe depression.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(12): 16-20