The 9th Zurich Hypertension Day focused on the changes to the European Hypertension Guidelines and the treatment of important concomitant or secondary diseases such as atrial fibrillation.

(rs) Probably the most striking change in the ESC/ESH guidelines concerned the relaxation of blood pressure target values in diabetics. While a target systolic of <140 mmHg continues to apply for patients at low to moderate risk (Cl. 1 Level B), the target systolic value for diabetics (cl. 1 Level A) raised to 135 mmHg. This is because of a lack of evidence for reduction in cardiovascular events at a target systolic of <130 mmHg. Whereas previous guidelines did not clearly recommend initiation of antihypertensive therapy in those over 80 years of age, treatment is now advised in this age group starting at a systolic blood pressure value of >160 mmHg. For the diastolic value, a limit of <90 mmHg applies, regardless of age. The exception is diabetics, for whom a target value <85 mmHg is aimed for.

It is known from the previous guidelines what the recommendation is for best prevention and quantification of overall cardiovascular risk. Now, the recommendation for risk stratification using the Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE) [1] also applies to asymptomatic patients with elevated blood pressure (cl. 1 level B). The resulting 10-year risk of a fatal cardiovascular event determines the next course of action.

Antihypertensive treatment

If it were up to the speaker and Deputy Clinic Director for Cardiology at Zurich University Hospital, Prof. Frank Ruschitzka, MD, therapy recommendations would take more account of the differences between the recommended drug classes. He referred primarily to the favorable results of the ACE inhibitor trials ADVANCE [2], HYVET [3], and ASCOT [4], in which a significant reduction in hard end points was demonstrated. In view of the results of the ASCOT [4] and ACCOMPLISH [5] trials, the cardiologist recommended the calcium antagonist amlodipine as the preferred combination partner for the ACE inhibitors. The combination had shown benefits in terms of morbidity and mortality compared with combinations of ACE inhibitor plus beta-blocker [4] or hydrochlorothiazide [5] and also proved beneficial in terms of renal function. The combination of ACE inhibitors with sartans is unsuitable, as shown by the ONTARGET study [6]. Which diuretic is appropriate for treatment depends on the glomerular filtration rate (GFR). A loop diuretic is indicated at a GFR <40 ml/min, whereas a thiazide or thiazide-like diuretic is used at a higher filtration rate. Prof. Ruschitzka primarily advocated the use of the thiazide-like agents chlortalidone and indapamide. These would have performed better than hydrochlorothiazide in studies.

Arterial hypertension and atrial fibrillation

“With arterial hypertension and atrial fibrillation (AF), two widespread diseases meet whose problems are potentiated and have unfavorable prognostic effects,” said Prof. Corinna Brunchkhorst, MD, Senior Physician at the Cardiology Clinic of the USZ at Hypertension Day.

There is a consensus that the treatment of VCF will continue to give rise to much work in the future. The current prevalence in Switzerland is about 100,000 persons. If one is guided by the prognosis of Miyasaka et al, this number is likely to double by 2050 [7]. “The combined occurrence of arterial hypertension and VCF results from the disease frequency and from the causal relationship,” the speaker said. She said that the electrical, mechanical, and structural remodeling triggered by hypertension leads to electrical instability, which triggers the atrial fibrillation career. As it progresses, a synergistic effect of hypertension and AF occurs, further supporting remodeling and sustaining AF.

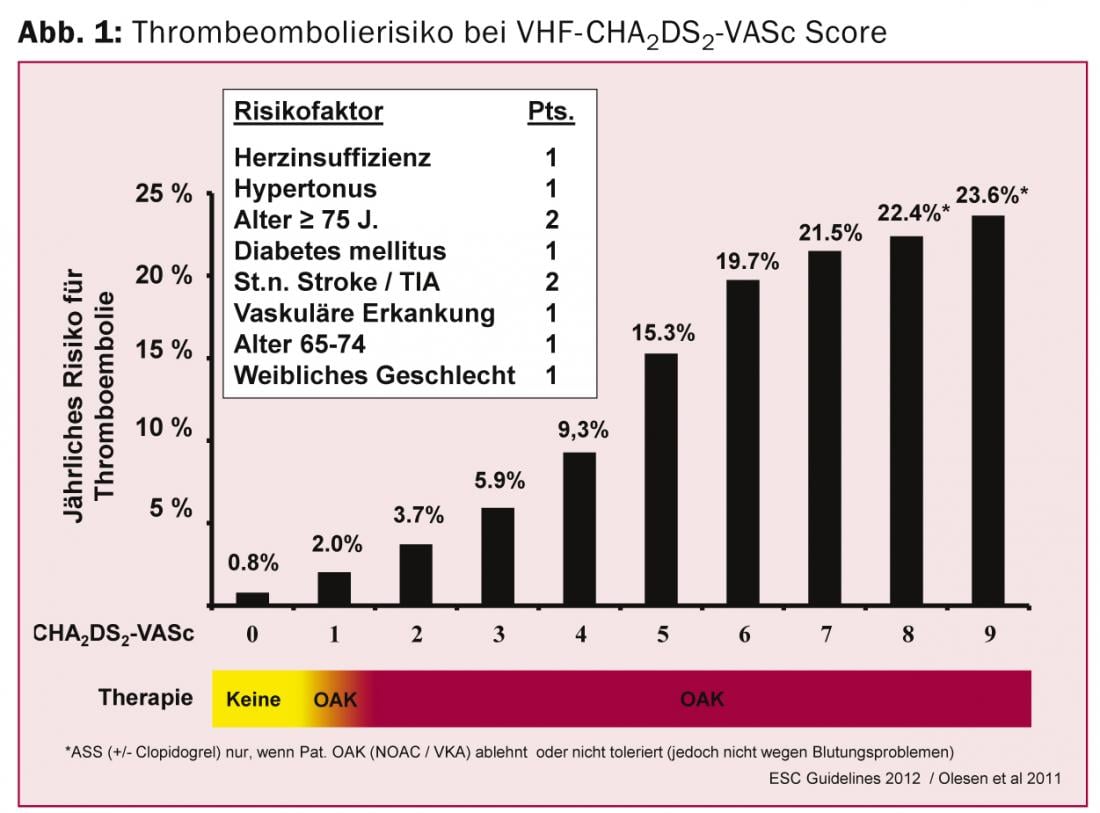

Because the incidence of VCF increases with age and any episode, however brief, is associated with an increased risk of stroke, the European Guidelines recommend screening by pulse measurement followed by ECG (cl. 1 level B) in patients >65 years of age [8]. Among the treatment goals, stroke prevention is at the top of the list. Risk assessment is performed using the CHA2DS2-VASc score and, based on this, the use of oral anticoagulants (Fig. 1) .

In the presence of concomitant arterial hypertension, the risk of stroke increases. With the goal of improving quality of life, the initial focus of treatment is frequency control, usually followed by rhythm control. “As we know from studies on arterial hypertension and VCF, ACE inhibitors and also sartans can be supportive in reversing remodeling,” the speaker explained. In patients with hypertension and VHF, the combination of these agents with an antiarrhythmic drug is often a useful therapy (upstream therapy). The decisive factor for the choice of antiarrhythmic drug is the presence of structural heart disease. In hypertensive patients, the choice is further influenced by the presence of left ventricular hypertension. If one is given, the guidelines recommend the use of dronedarone or amiodarone. Dronedarone is contraindicated in permanent VHF or heart failure. Prof. Brunckhorst explained the various proarrhythmic side effects of the antiarrhythmic drug classes, in particular reentry (class 1C) and torsade de pointes tachycardias (class 3), and in which constellations of findings special caution is required.

In addition to pharmacologic conversion, electrical cardioversion-often in combination with drug therapy-is another option for rhythm control. Radiofrequency ablation (catheter ablation) has also gained in importance with the new guidelines. This shows success rates of about 80% and a complication rate of only 2-3% and is superior to drug treatment.

Catheter ablation is used particularly for paroxysmal VHF, with special consideration of patient preference. In cases of persistent fibrillation or structural heart disease, the guidelines recommend that ablation be indicated after one to two attempts at drug therapy. “It is important that ablation treatment is started early in hypertensive patients with VCF, rather than when remodeling is already advanced,” Prof. Brunckhorst said. With the combination of catheter ablation and renal denervation, the speaker ventured a glimpse of future therapies that are hoped to have a synergistic effect: “Smaller studies are promising, now larger ones must follow.”

Source: 9th Zurich Hypertension Day, January 23, 2014, Zurich

Literature:

- ESH/ESC Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension. 2013 Practice guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC): ESH/ESC Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2013; 31(10): 1925-1938.

- ADVANCE Collaborative Group. Effects of a fixed combination of perindopril and indapamide on macrovascular and microvascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the ADVANCE trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007; 370(9590): 829-840.

- HYVET Study Group. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2008; 358(18): 1887-1898.

- ASCOT Investigators. Prevention of cardiovascular events with an antihypertensive regimen of amlodipine adding perindopril as required versus atenolol adding bendroflumethiazide as required, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005; 366(9489): 895-906.

- ACCOMPLISH Trial Investigators. Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359(23): 2417-2428.

- ONTARGET investigators. Renal outcomes with telmisartan, ramipril, or both, in people at high vascular risk (the ONTARGET study): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet. 2008; 372(9638): 547-553.

- Miyasaka Y1, et al: Secular trends in incidence of atrial fibrillation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980 to 2000, and implications on the projections for future prevalence. Circulation. 2006; 114(2): 119-125.

- Camm AJ1, et al: 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation–developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association.

- Eur Heart J. 2012; 33(21): 2719-2747.

CARDIOVASC 2014; 13(2): 36-38