Within the framework of this year’s Swiss Oncology and Hematology Congress (SOHC), which took place completely virtually for the first time from November 18 to 21, PD Dr. med. Bernhard Gerber, Head Physician Hematology at the Regional Hospital Bellinzona, presented experiences and findings in dealing with coagulopathy in COVID-19. From the front line, he reported on the situation in Ticino, therapy options and current studies.

As an Italian-speaking canton with geographic proximity to Bergamo, Ticino was particularly hard hit during the first wave of the Corona pandemic in March. In addition to the high number of cases, which posed major challenges for physicians and nurses, there was the fact that almost half of all people working in the health care professions come from nearby foreign countries and many of them are cross-border commuters. Also currently, more positive test results are reported in Ticino compared to German-speaking Switzerland [1]. In particular, it is striking that on the other side of the Gotthard, disproportionately more elderly persons are infected with the virus. In Ticino, for example, people over 70 account for just under a quarter of all those affected, compared with 13% in Switzerland as a whole – an important factor when one considers that both age and frailty have a significant influence on the death rate. In the midst of the critical situation was and is Dr. Gerber, who now spoke about his impressions and gave insights into the scientific workup of the coagulopathy triggered by SARS-CoV-2.

COVID-19: Not just a lung disease

As the head physician for hematology at the Bellinzona Hospital, Dr. Gerber can well remember the day he was contacted by Professor Casini from Geneva about a possible link between SARS-CoV-2 infections and the increased number of thromboses. It was March 25, 2020. Up to that point, he said, he had not noticed an increased risk of thrombosis in COVID-19 patients. What followed, however, was a flood of information about virus-associated coagulopathy that inundated social media in particular. Reliable data from the scientific side, on the other hand, had been scarce. In this extremely unclear situation, various Italian and Swiss experts jointly decided to integrate thrombosis prophylaxis into the therapy starting in April. Especially in hospitalized patients, enoxaparin was used and D-dimer progression was closely monitored. A rapid rise in laboratory D-dimers was considered an indication for higher doses of antithrombotic treatment. Thromboprophylaxis was also considered for outpatients.

Analysis of this first hematologic therapy for COVID-19 sufferers showed that no disseminated intravascular coagulopathy or heparin-induced thrombocytopenia occurred among the 270 patients treated, but 14 individuals suffered severe bleeding and 3 even died from blood loss. Dr. Gerber considers the pattern of hemorrhages, which were almost exclusively retroperitoneal or muscular and occurred after more than two weeks of hospitalization, to be exceptional. In addition, closer examination of data from intensive care units revealed that although the incidence of deep vein thrombosis decreased with anticoagulation, many patients continued to experience catheter-associated thrombosis, particularly of the jugular vein. In addition, more bleeding occurred with a higher, therapeutic dose of anticoagulation and with additional antiplatelet therapy.

After the first use of anticoagulant drugs in the treatment of COVID-19 patients in Switzerland, physicians were now faced with the situation last summer that anticoagulation in therapeutic doses seemed to cause too high a risk of bleeding. On the other hand, there was a great cry for adequate therapy of coagulopathy. As a compromise, anticoagulation at intermediate or high prophylactic doses for no longer than 10 days was used in hospitalized patients where possible.

SARS-CoV-2 and the antiphospholipid antibodies.

To shed some light on what remains a relatively unclear situation, Dr. Gerber and his colleagues not only investigated the benefits and risks of anticoagulation but also sought to understand relevant pathomechanisms. This is where antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL AK) came into play. Thus, based on a publication in the New England Journal of Medicine with only three patients, 157 affected individuals from La Carità Hospital in Ticino were systematically screened for lupus anticoagulant and aPL AK (2). While lupus anticoagulant was detected in 41.6% of patients, approximately 15% of those studied tested positive for aPL antibody. A first follow-up took place after three months. The data collected are currently still being analyzed, but the lupus antioagulant ratio seems to decrease during the course, whereas the aPL AK titer was stable or slightly increasing in the first analyses.

Anticoagulation, yes or no?

Regardless of causation, data from Lausanne show that after the introduction of anticoagulation in hospitalized COVID-19 patients, the rate of thromboembolic events decreased significantly, from 7.7 to 3.4 per 1000 patient days. The data situation is even clearer when the situation for intensive care patients is considered in isolation. For example, in this patient group, the rate of thromboembolic events decreased from 18.5 per 1000 patient days in March to 4.9 per 1000 patient days in April. Among outpatients, the newly introduced anticoagulation reduced the incident rate from only 6.8 to 5.2 per 100 presentations.

Apart from these impressive data, which have not yet been published, Dr. Gerber also presented promising study results on the value of D-dimers in diagnostics. Thus, values below 2000 ng/ml showed a negative predictive value of 100% for venous thromboembolism, and a corresponding increase was an extremely good predictor for the imminent diagnosis of an event. In most cases, D-dimers rose slowly about five days before diagnosis by imaging.

New wave, new recommendations, new studies

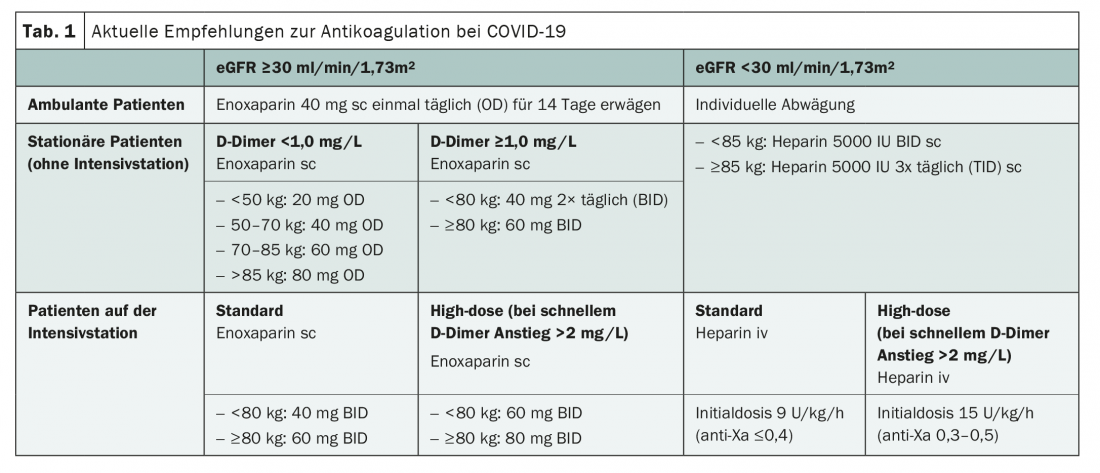

With the findings from Ticino and the Centre hospitalier universitaire vaudois (CHUV) , and taking into account current literature, Dr. Gerber also presented new recommendations for anticoagulation for the new COVID-19 wave (tab. 1) . These provide for a therapy adapted to D-dimer levels for hospitalized patients. He repeatedly emphasized that a highly prophylactic dose should be reduced to a regular prophylactic dose after ten days at the latest, if possible, to prevent bleeding complications.

Two clinical trials are also currently underway, which aim at a more precise characterization of coagulopathy and its optimal therapy. On the one hand, the Geneva COVID-HEP Trial compares thromboprophylaxis with therapeutic anticoagulation in hospitalized patients. On the other hand, the Zurich OVID Trial is investigating the benefit of thromboprophylaxis in 1000 outpatients. With new findings, the recommendations will certainly undergo some changes as well.

Source: Swiss Oncology & Hematology Congress Nov. 18-21, 2020, On Demand Session “COVID-19 and Hemostasis – Swiss experience: APL, bleeding, thrombosis, and thromboprophylaxis,” PD Dr. med. Bernhard Gerber, Senior Physician Hematology at the Regional Hospital Bellinzona, published online Nov. 9, 2020.

Literature:

- Federal Office of Public Health FOPH: Covid-19 Switzerland: Information on the current situation, as of November 13, 2020. www.covid19.admin.ch/de (last accessed 11/14/2020)

- Zhang Y, et al: Coagulopathy and Antiphospholipid Antibodies in Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020; 382(17): e38.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2020; 8(6): 34-35 (published 10/12/20, ahead of print).