Between 30 and 80% of all cancer patients are malnourished at diagnosis. Malnutrition increases mortality and morbidity and decreases the tolerability of tumor therapies. Screening for malnutrition using established measurement tools is part of any tumor therapy. The goals of stepwise nutrition therapy are to treat malnutrition, improve quality of life, improve the efficacy of tumor therapies, and reduce side effects. A ketogenic diet is not recommended.

A common finding in cancer patients is tumor cachexia. Cachexia represents weight loss that is predominantly caused by an altered metabolic state, usually due to the tumor itself. It is a complex, metabolic-endocrine condition. Weight loss affects not only the body fat percentage, but also the muscles. Patients suffering from cachexia may additionally have a loss of appetite.

Three stages of cachexia are distinguished: precachexia, cachexia, and refractory cachexia. Precachexia is referred to when weight loss is less than 5% and metabolic changes are present. Refractory cachexia often occurs in the terminal stage of tumor disease. The metabolism is then catabolic, and the remaining life expectancy is usually less than three months.

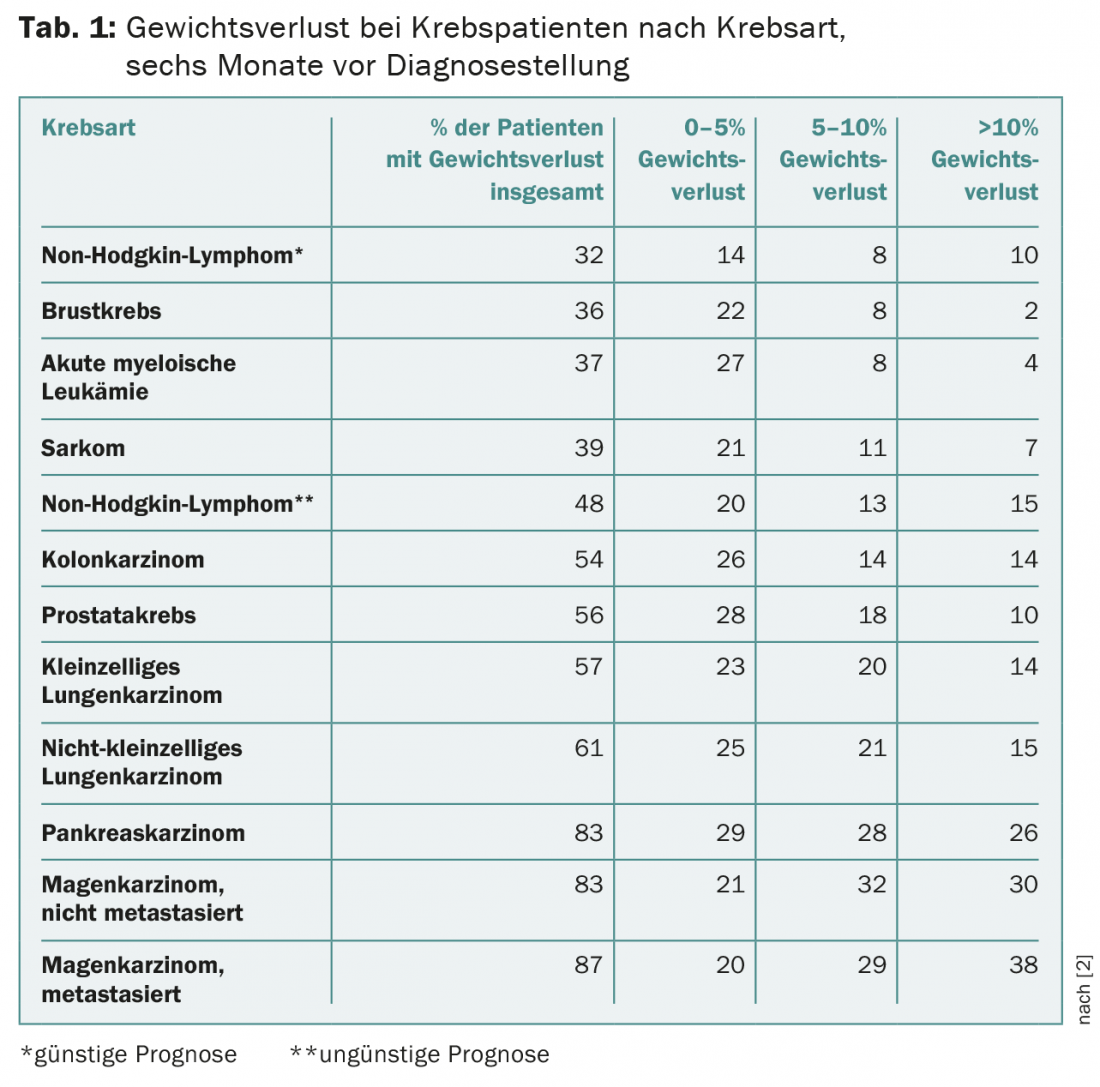

Depending on tumor progression and location, 30-80% of patients are already malnourished at diagnosis. As early as 1980, Dewys et al. show that between 31-87% of patients were malnourished before diagnosis. At the time of diagnosis, 16% of patients were severely malnourished (Table 1).

Causes of malnutrition

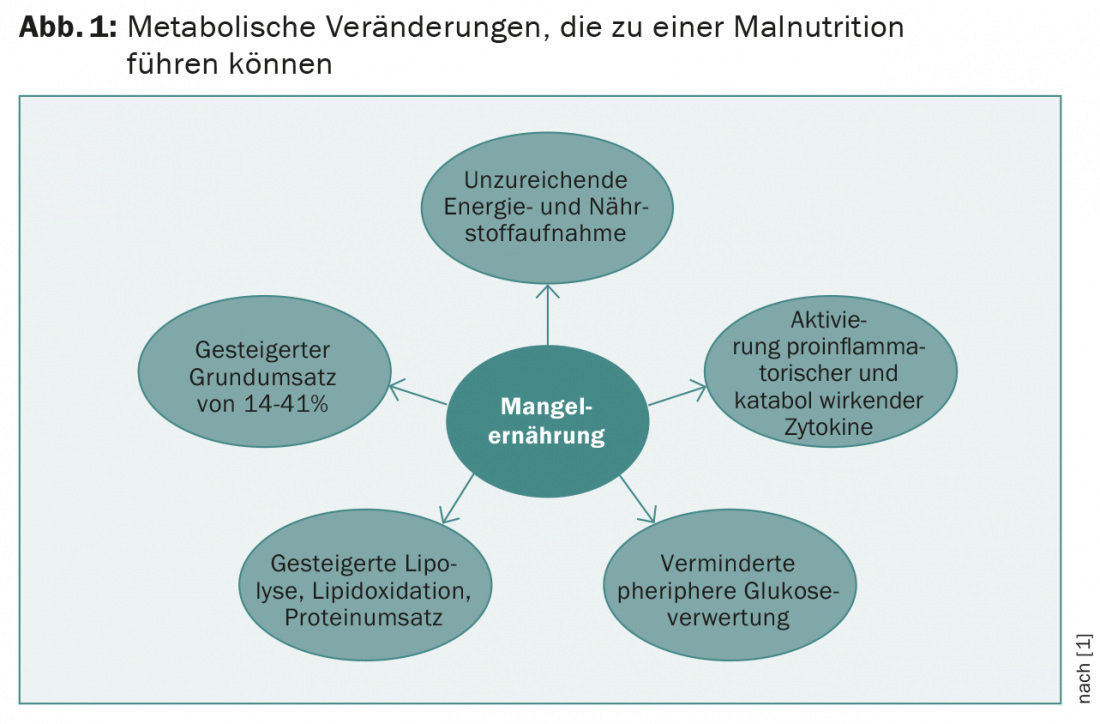

Tumor-associated metabolic changes result in malnutrition. One of the causes is decreased food intake. This is caused by decreased appetite, taste changes, psychological effects, and xerostomia, among others. However, dehydration and sarcopenia are also characteristic determinants. Systematic activation of proinflammatory and catabolic cytokines (tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1, interleukin-6, interleukin-8, interferon-γ) plays a central role. In addition, lipolysis, lipid oxidation, and protein degradation are increased. Catabolism of muscle proteins is additionally promoted by procachectic cytokines. Basal metabolic rate may be increased by 14-41%. Altered hormonal status (testosterone, thyroid and growth hormones) also contributes to the development of cachexia (Fig. 1).

As a result of malnutrition, mortality is increased. Likewise, the risk for morbidity increases. These are wound healing disorders, increased risk of decubiti, infections and organ dysfunction. Furthermore, the tolerability of tumor therapies decreases.

Recognize malnutrition

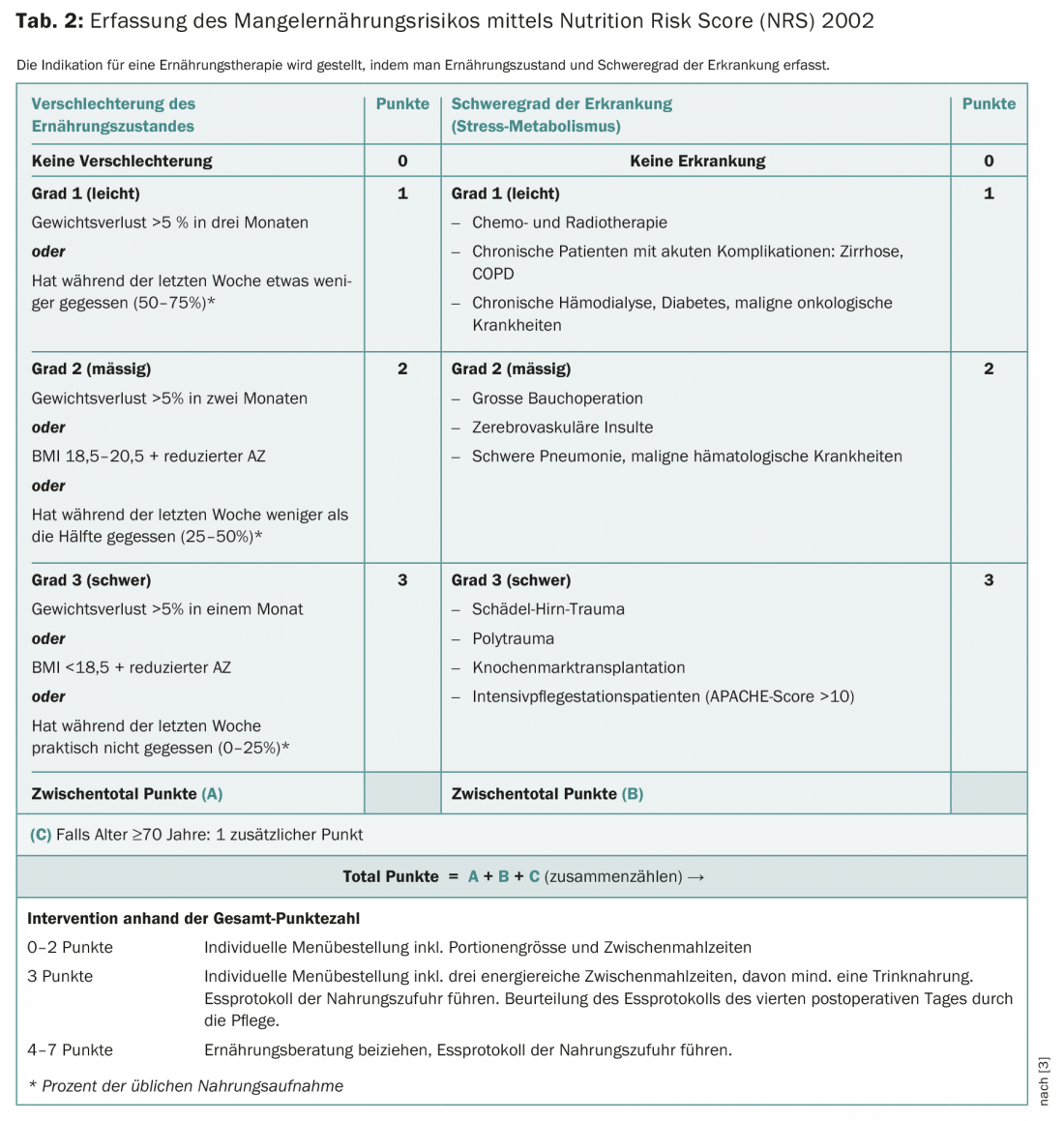

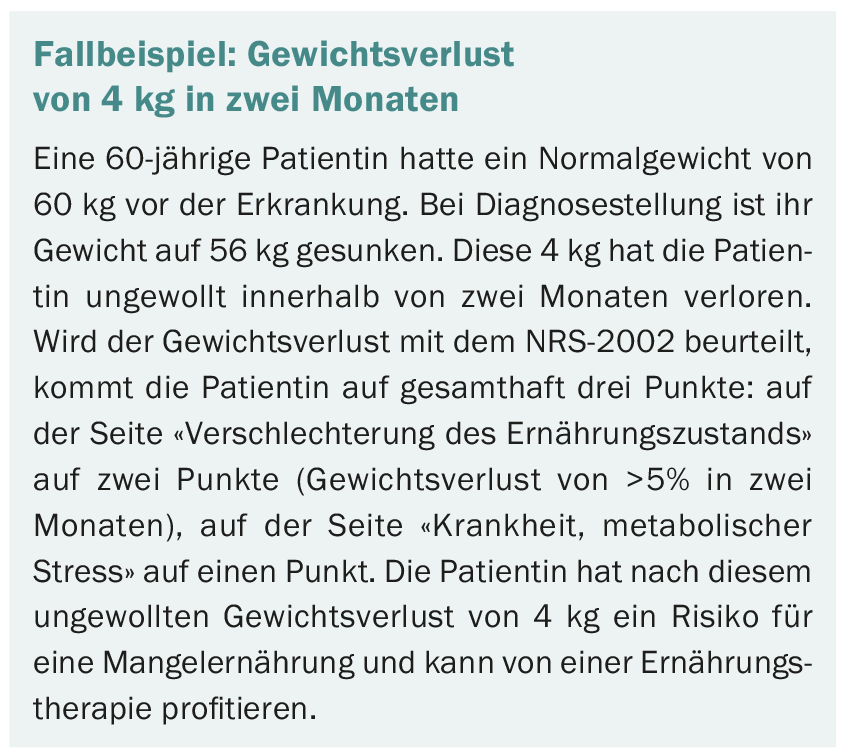

Screening for malnutrition using established measurement tools is a component of any tumor therapy. The Nutrition Risk Score-2002 (NRS-2002) or the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) are suitable for this purpose. In clinical practice, the NRS-2002 has proven to be a validated screening instrument (Table 2) .

It consists of a prescreening with four questions:

- Is the BMI less than 20.5 kg/m2?

- Weight loss in the last three months?

- Reduced food intake in the past week?

- Is there a serious illness?

If a question is answered yes, the screening must be completed. Nutritional therapy should be initiated at ≥3 points (see case report).

An implementation study from Denmark showed that the assessment of patients’ risk status by healthcare professionals and, in each case, by the principal investigator virtually always agreed, regardless of whether screening using NRS-2002 was performed by dietitians or nurses. Kondrupt et al. were able to demonstrate the user-friendliness of the NRS-2002 by screening 99% of 750 patients entering the hospital.

Principles of nutrition therapy for cancer

That nutritional therapy for malnutrition improves prognosis is not clearly established. However, patients benefit from a better response to tumor therapy as well as reduced side effects during therapy. The goals of nutrition therapy in patients with cancer are:

- Recognition, prevention and treatment of malnutrition

- Improving the quality of life

- Improve the effect of tumor therapies

- Reduce side effects of tumor therapies.

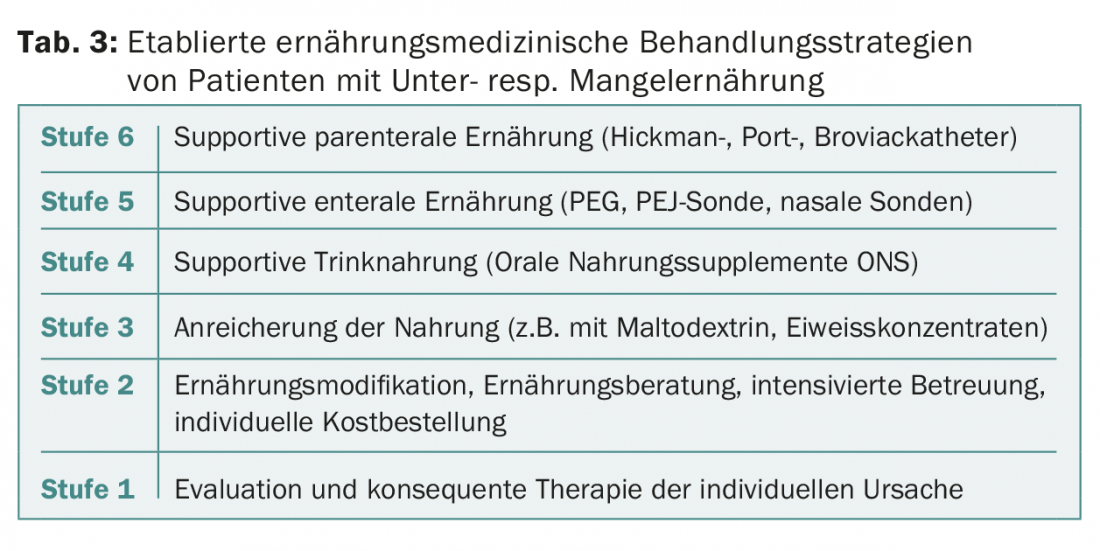

Nutritional therapy for malnourished tumor patients is divided into six stages. The nutrition therapy nutrition strategy is a valid guideline of the German Society for Nutritional Medicine (DGEM), the European Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ESPEN) and the German Society for Geriatrics (DGG). From an NRS-2002 ≥3, nutritional therapy is indicated (Table 3) . Ideally, nutritional therapy should start in the phase of precachexia, but at the latest in the phase of cachexia. In the refractory cachexia phase, the benefit of nutrition therapy is no longer present.

Energy and protein requirements

The energy requirement is calculated as follows:

Immobile patients: 20-25 kcal/kgKG/day.

Without weight loss: 30-35 kcal/kgKG/day

With weight loss: 35-40 kcal/kgKG/day

The protein requirement is calculated as follows:

Without weight loss: 1.2-1.5 g/kgKG/day

With weight loss: 1.5-2.0 g/kgKG/day.

Carbohydrate requirements are between 40-50% of total energy intake. Carbohydrate requirements in cancer therapy are discussed in both lay forums and professional journals. Two questions loom: Does a ketogenic diet prevent or reduce tumor growth? Does a high protein, high fat diet reduce tumor progression or risk of recurrence?

Studies on the ketogenic diet in cancer patients to reduce tumor growth are many. Electronic databases such as Pubmed and Cochrane Library display more than 270 studies, both human and animal. A difference in tumor growth and survival has been noted in animal studies, but has not yet been shown in human studies. Therefore, the recommendation for the ketogenic diet is abandoned.

Whether a diet high in protein and fat reduces the risk of recurrence cannot be said with certainty. The prospective observational study by Meyerhardt published in 2012 shows a significant correlation between glycemic load resp. of total carbohydrate intake and risk of recurrence. In cancer patients who lose weight and have increased insulin resistance, it is recommended to increase fat intake at the expense of carbohydrate intake (ratio 50:50), both to reduce glycemic load and to increase dietary energy density.

High energy diet

A high-energy diet is necessary in most cases. The basis of nutritional therapy is food fortification. This maintains or improves energy intake despite the reduced food intake. Fortification is achieved through foods with high energy density such as vegetable oils, whole cream, butter, nuts, avocados, coconut milk, honey, birnel, condensed milk, cream curd, etc. If these measures are not sufficient, maltodextrin and protein powders can be additionally stirred into food and beverages. One tablespoon of maltodextrin provides about 9 g of carbohydrates and 38 kcal, and one tablespoon of protein powder provides about 9 g of protein and 38 kcal.

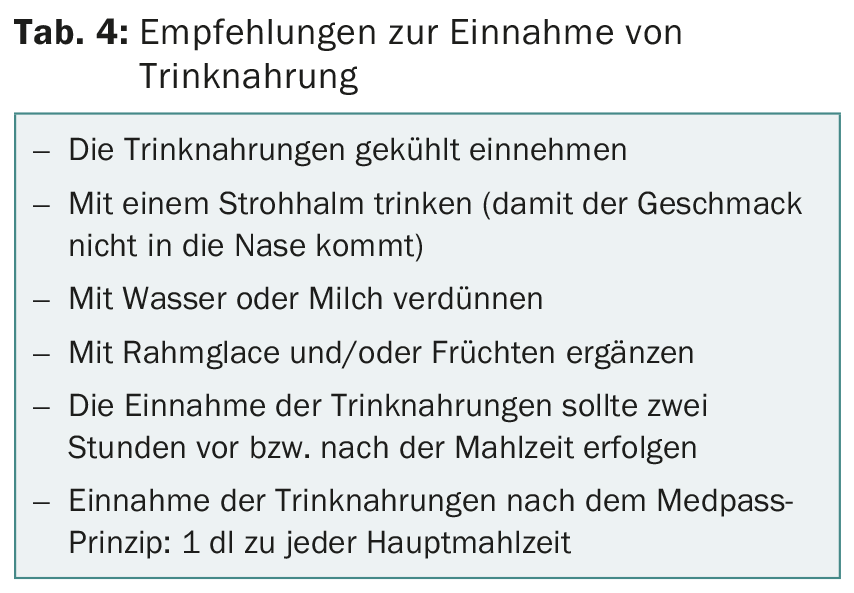

Sip feeds are another tool of nutritional therapy for malnourished tumor patients. Efficacy is supported with a level of evidence of A for radiation, high nutritional risk 10-14 days before major surgery, and in all patients five to seven days before major abdominal surgery (ESPEN Guidelines Oncology 2006). In malnourished and ambulatory tumor patients, studies by Poulsen and Usler demonstrated improved coverage of energy and protein requirements, although no significant improvement in quality of life was evident. A detailed discussion with patients about the options and benefits of sip feeds is therefore essential (Table 4).

Special nutritional situations

In tumor diseases and therapies, complaints such as changes in taste, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, xerostomia and stomatitis may occur, especially in the mouth, throat and gastrointestinal tract. The nutritional treatment of these complaints is very important and requires individual nutritional counseling, which specifically supports and accompanies those affected.

Literature:

- van Cutsem E, et al: The causes and consequences of cancer-associated malnutrition. Europ J Oncology Nursing 2005; Supplt 2: S51-63.

- DeWys WD, et al: Prognostic effect of weight loss prior to chemotherapy in cancer patients. Am J Med 1980; 69: 491-497.

- Kondrup J, et al: Nutritional risk screening (NRS 2002): a new method based on an analysis of controlled clinical trials. Clin Nutr 2003; 22(3): 321-336.

Further reading:

- van Eys J: Effect of Nutritional Status on Response to Therapy. Cancer Research 1982; (Suppl.) 42: 747s-753a.

- Fredix EW, et al: Effect of different tumor types on resting energy expenditure. Cancer Res 1991; 51(22): 6138-6141.

- Arends J, et al: ESPEN Guidelines on Enteral Nutrition: Non-surgical oncology. Clin Nutr 2006; 2: 245-259.

- Farber G, et al: Cancer and nutrition. Oncologist 2011; 17: 906-912.

- Meyerhardt JA, et al: Dietary glycemic load and cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage 3 colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012; 104(22): 1702-1711.

- Poulsen GM, et al: Randomized trial of the effects of individual nutritional counseling in cancer patients. Clin Nutr 2014; 33: 749-753.

- Uster A, et al: Influence of a nutritional intervention on dietary intake and quality of life in cancer patients: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Nutr 2013; 29: 1342-1349.

- Evans WJ, et al: Cachexia: A new definition. Clin Nutr 2008; 27: 793-799.

- Kondrup J, et al: Incidence of nutritional risk and causes of inadequate nutritional care in hospitals. Clin Nutr 2002; 21: 461-468.

- Valenthi L, et al: Guideline of the German Society for Nutrition. Current Ern.medizin 2013; 38: 97-111.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2015; 3(9-10): 26-30.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(8): 11-15