The care situation of borderline personality disorder is deficient compared to other disorders until now. The SGPP treatment recommendations published in 2018 are expected to change this in the future by providing simplified treatment concepts (so-called “General Intervention Principles”) for clinical professionals in different settings in addition to disorder-specific treatment procedures.

Compared to other disorders (e.g., depression, schizophrenia), the care situation for borderline personality disorder is still poor [1]. The SGPP treatment recommendations* published in 2018 are intended to change this in the future by providing simplified treatment concepts (so-called “General Intervention Principles”) for clinical professionals in different settings in addition to disorder-specific treatment procedures. An important criterion is that the treatment recommendations are evidence-based and relevant to practice, i.e. correspond to “Good Clinical Practice”, according to Sebastian Euler, MD, University Psychiatric Clinics Baselland, in his introductory presentation at the SGPP Congress [2]. To date, psychotherapy is the only evidence-based treatment for borderline personality disorder [3]. Consideration of clinical applicability is of particular concern to the authors, as evaluation studies have shown that implementation of treatment guidelines in everyday clinical practice is a critical issue [4]. Three major components of the newly released treatment recommendations for borderline personality disorder were presented at the SGPP symposium:

- General principles of treatment (so-called “general intervention principles”)

- Disorder-specific therapies (e.g., dialectical-behavioral therapy, schema-focused therapy, mentalization-based therapy, transference-focused therapy).

- Drug options (pharmacotherapy)

https://www.medizinonline.ch/sgpp2017

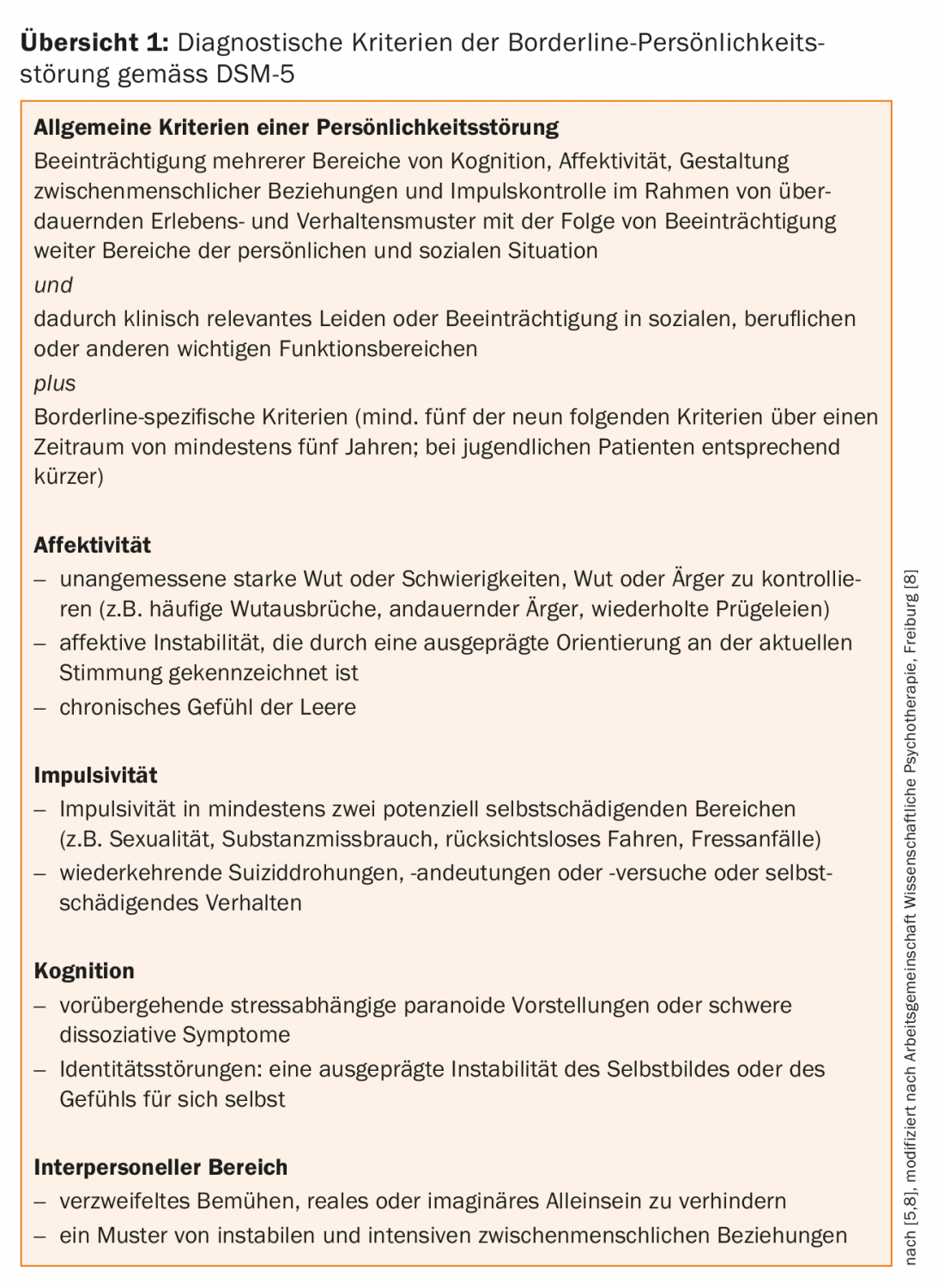

Borderline personality disorder is a disorder that is relatively common among patients in outpatient psychiatric care facilities and in inpatient departments of psychiatric or somatic hospitals. According to Sebastian Euler, MD, there is a relatively high number of unreported cases in which a borderline personality disorder was incorrectly assessed as a treatment-resistant depressive disorder or assigned to the frequently occurring comorbidities (e.g., addictive disorder, anxiety disorder, depression). According to DSM-5 [5], emotion regulation disorders, impulsivity, and impairments in social relationships are among the core symptoms of borderline personality disorder (overview 1). In ICD-10, the diagnostic classification is as follows: Emotionally unstable personality disorder, borderline type (F60.3) [6]. Self-injurious behavior, suicidality, interpersonal problems, and comorbid illness present special therapeutic challenges. According to PD Dr. med. Dr. phil. Daniel Sollberger [7], Psychiatrie Baselland, self-injurious behavior can be explained as follows: An emotion that is avoided is acted out in the form of a bodily reaction (e.g., feeling of pain). Avoidance of certain emotions is attributed to a failure to respond appropriately to related needs and feelings in the past. Emotion regulation disorders are associated with increased sensitivity to emotional stimuli, heightened response to them, and delayed return to normal arousal. The fact that borderline personality disorder is a heterogeneous disorder has only been recognized in recent years, according to Sebastian Euler, MD. In this context, a dimensional diagnosis is recommended, in which differentiation is made according to the severity of the psychosocial impairment. There are studies that show that adequate therapy of borderline personality disorder can lead to remission within a period of two to three years on average, i.e., symptoms are no longer present. Appropriate treatment concepts can therefore make an important contribution to improving the diagnosis and treatment of borderline personality disorder.

General principles of intervention

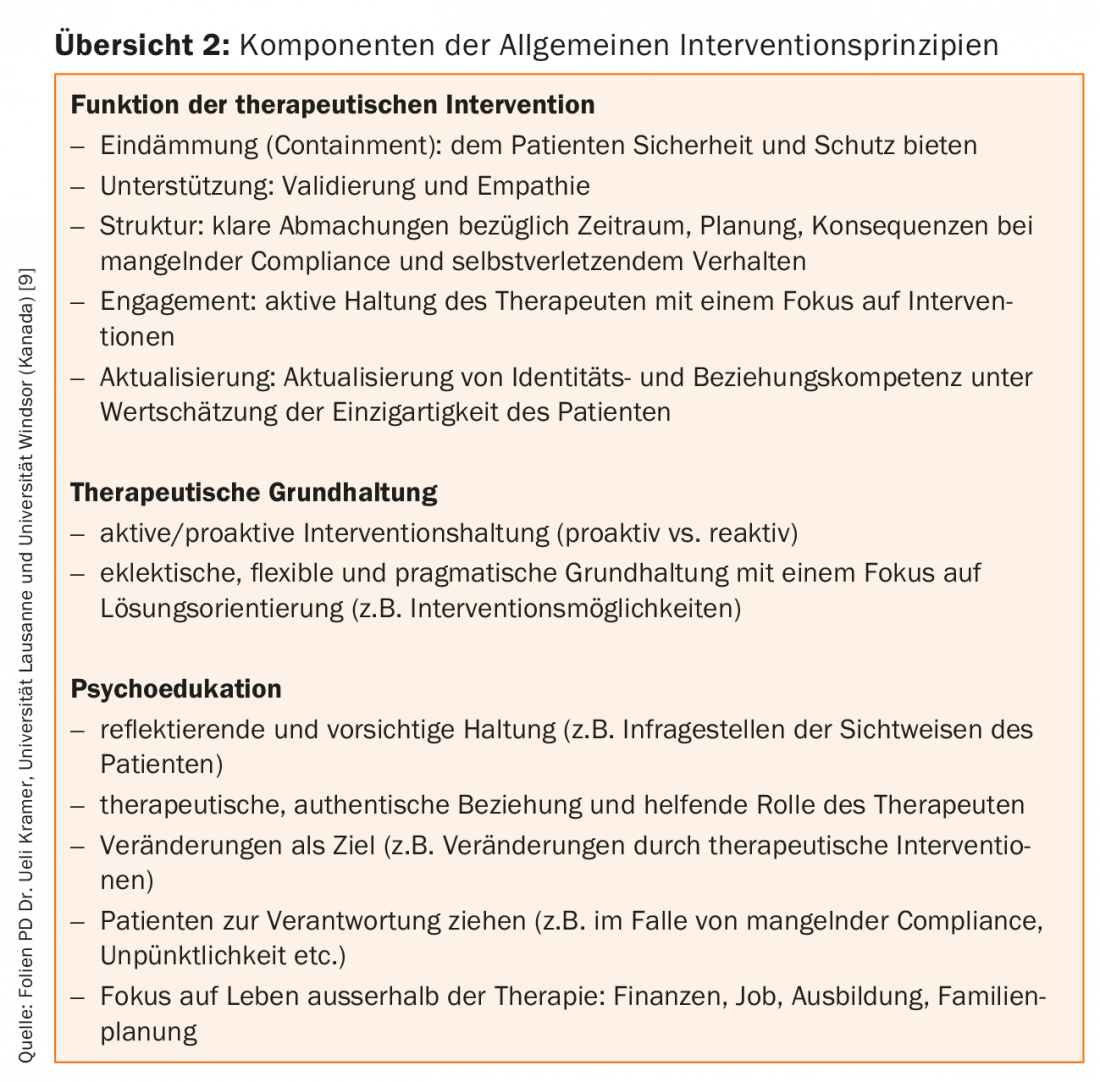

General intervention principles for the treatment of borderline personality disorder serve therapeutic professionals who are not specialized in the treatment of this disorder as a basis for the clinical care of patients with borderline personality disorder, according to PD Dr. Ueli Kramer, University of Lausanne and University of Windsor (Canada), in his presentation on this topic [9]. In the treatment recommendations, the “General Intervention Principles” are summarized in a compact form on two pages. In terms of content, these are minimum requirements for the treatment of this disorder. Because specialized training for disorder-specific forms of treatment (e.g., dialectical-behavioral therapy, schema therapy, mentalization-based therapy, transference-focused therapy) is very resource intensive, there is a shortage of appropriate therapy services. Therefore, simplified treatment concepts, limited to the essentials, are needed for the training of professionals who deal with patients with borderline personality disorder in clinical practice. The concept of General Intervention Principles includes the following three components (overview 2): Function of Therapeutic Intervention, Basic Therapeutic Approach, Psychoeducation.

PD Dr. Ueli Kramer emphasizes that psychoeducation plays a central role in the psychotherapeutic treatment of borderline personality disorder. The aim is, among other things, to discuss the diagnosis openly and directly and to show the patient the individual aspects in the therapy using concrete examples. This is on the background that the development of a reality-based focus is supported, which should contribute to a constructive discussion of the problem (e.g. self-injury, identity problems, coping with everyday life) and cooperation with regard to therapy goals. The patient should feel that the therapist understands the problem and correctly assesses the need for action. Proper classification of the various components of the disorder is also important for dealing constructively with countertransference. Furthermore, it should be pointed out to the patient that research findings and empirical data show that borderline personality disorder is treatable and that therapy can remit the acute symptoms (impulsivity, self-injurious behavior, some affective symptoms). It may also be possible to draw attention to the fact that the so-called “temperamental symptoms” according to the DSM [5,10] such as disorders of anger regulation, dissociative and cognitive symptomatology, on the other hand, often persist and only about half of all patients with borderline personality disorder manage to adapt well in social and occupational areas. Explanatory models can also be part of psychoeducation, for example, by teaching patients that borderline personality disorder is the result of a multifactorial interaction of biological and psychological determinants and that there is no monocausal explanation. The aspect of hypersensitivity should be directly addressed in therapy and analyzed with concrete examples regarding the patient’s feelings and possible coping strategies. Disruptive interaction patterns and their consequences should also be addressed directly and concretized using everyday examples (e.g., fear and rejection as possible reactions of others to self-injurious behavior). Psychoeducation also includes education about what psychotherapeutic treatment does and does not involve. This should be explained as clearly as possible with an indication that client engagement is also required. The modalities of therapy (e.g., frequency of therapy) can also be addressed during psychoeducation.

Disorder-specific psychotherapy procedures: The “Big Four

Research findings confirm the substantial role of psychotherapy in the treatment of borderline personality disorder, as PD Dr. med. phil. Daniel Sollberger explained in his paper on disorder-specific psychotherapeutic procedures [7]. Among the most empirically studied disorder-specific therapies are: Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT), Schema Therapy (SFT), Mentalization Based Therapy (MBT), Transference Focused Therapy (TFP). All four therapeutic approaches mentioned are manualized procedures that have been empirically validated in randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The four therapy methods have the following common features: Structuring (e.g., frameworks and agreements), high therapist activity, clarifying attitude of the therapist, work on and with the relationship, focus on self- and other-damaging behaviors (incl. therapy-damaging behaviors), treatment focus in the here and now, encouragement for independent and self-effective behavior.

Dialectical-Behavioral Therapy (DBT): DBT is the therapy method with the best empirical validation based on several RCTs and meta-analyses (evidence level 1a [11]). DBT was developed by Marsha M. Linehan [12] as a disorder-specific treatment for borderline personality disorder in the 1980s. It is a therapeutic method with behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based components (e.g., elements from Gestalt therapy and Zen Buddhism).

The basic attitude is a dialectic between acceptance (for dysfunctional coping patterns and emotions) and willingness to change. In DBT, relationship building is characterized by clarity, openness, and validation. DBT is structured by clear algorithms (hierarchy of treatment goals) and is strongly oriented towards patients’ resources and competencies.

Outpatient DBT includes the following four components: Individual therapy, group therapy, telephone coaching, supervision. In individual therapy, diagnostics, psychoeducation and treatment agreements are central elements. The group therapies are so-called skills groups, i.e. training in the areas of stress tolerance, dealing with emotions, social skills. Telephone coaching refers to a type of crisis intervention and has a special significance for the implementation of what has been learned in therapy into the patient’s everyday life.

The overall therapy goals can be summarized as follows: Change of a dysfunctional behavior pattern and therapy-disrupting behavior, modulation and change of one’s own emotion regulation, and psychosocial integration (work, relationships, leisure activities, etc.).

Schema Therapy (SFT): SFT was developed in the 1990s by Jeffrey Young [13] and is based on cognitive therapy. A central construct is affective-cognitive schemas, which refer to a pattern based on emotions, bodily sensations, and feelings that are thought to originate in childhood. Underlying formative experiences of the schemas can be, for example, frustrations of basic psychological needs, victimization, pampering, and lack of boundaries.

It is assumed that these schemas manifest themselves in different situations in the so-called modes and can lead to certain dysfunctional behaviors (e.g., avoidance, submission, overcompensation). The following five key modes are distinguished: child mode refers to a mode in which patients feel like an abused or abandoned child or experience themselves as an angry or impulsive child because they may experience frustration or be denied something. Dysfunctional coping styles, such as emotional detachment and dissociative states, are characteristic of the distant protector mode. In parent mode, patients perceive themselves as a bad child versus a punitive parent. The adult mode is a mode where the different parts are integrated, which would be the goal. The interventions at a glance:

- “Limited Parenting”/”Re-Parenting”: attempts to make up for lack of childhood emotional care in therapy. For therapists, associated with increased risk of countertransference (i.e., getting personally involved with patient’s person and establishing emotional relationship).

- Emotion-centered techniques: Dialogue design with role-playing (e.g., parent vs. child position).

- Cognitive processing: psychoeducation about normal basic needs of a child, restructuring (behavior modification with pro-con lists).

The following therapeutic phases of SFT are distinguished: establishment of the therapeutic relationship and affect regulation, change and reorganization of psychological schemas concerning autonomy development. Key therapy goals include working on schemas and dysfunctional coping styles.

Mentalization-based therapy (MBT): MBT originated from a research group led by Bateman and Fonagy [14,15], who first developed MBT for day-patient settings and later for outpatient settings. It is an eclectic approach to therapy that combines elements of cognitive science, psychoanalysis, developmental psychology, and neurobiology. MBT is an evidence-based procedure whose efficacy has been demonstrated in several RCTs with multi-year follow-up intervals [16]. Central aspects of MBT are work on relationship patterns and mentalization. Mentalization refers to the understanding of one’s own mental states and those of others and includes the following dimensions: Integration of cognition and affect, self- and other-orientation, internal and external focus. The basic assumption of MBT is that mentalization underlies behavior and action and that changing mentalization processes is a starting point for experience and behavior modification. Prementalistic modes are defined as a phase preceding mentalizing and are assumed to be reactivated in attachment-relevant situations and to be an expression of threatened self-coherence. The following three prementalistic modes are distinguished:

- Teleological mode: Only real observables are of importance and motives of others are judged solely on the basis of their visible actions.

- Equivalence mode: Inner world and outer reality are experienced as identical and alternative perspectives are rejected.

- As-if mode: playing with reality; mental state without implication for the external world and vice versa (not all mentalisitic/mental capacity is yet developed); dissociative phenomena.

Interventions focus on affect and the interpersonal domain. A so-called intervention hierarchy is based on changes in emotional arousals, the so-called emotion level. The attitude of the therapist corresponds to the so-called “collaborative stances”. This means that the therapeutic professional presents himself naively and responds to the patient in the form of questions, which should cause the patient to reflect on himself and his inner self. In group therapy, the introduction of different perceptions should bring about a relativization of one’s own view (change of perspective). A curious-self-explorative attitude (“inquisitive stances”) should be encouraged with the overall goal of improving mentalization.

Transference Focused Therapy (TFP): Transference Focused Psychotherapy (TFP) is based on the diagnostic model of personality organization (BPO). It is assumed that a personality organization with identity problems (identity diffusion), expressing itself in immature defense mechanisms with preserved reality testing, is a central underlying mechanism of borderline symptomatology (dysfunctional behavior patterns, extreme affective reactions, cognitive distortions of perception and thinking). Identity diffusion is a split into good and evil that cannot be integrated internally; the other person is experienced only as good or evil and in the self-image the same happens with the consequence of corresponding emotional reactions. The transference relationship (therapeutic dyad) is considered the starting point of treatment, with the focus of the therapeutic process in the here and now. By reactualizing dissociated and projected parts of the self, their processing should be able to take place in situ. Interventions represent the concept and structure of treatment according to TFP, distinguishing between strategies, tactics and techniques. Strategies are the long-term goals; these include definition of dominant object-relations dyads, interpretation of role changes and averted dyads, and integration. Tactics include the following elements: therapy agreements, clarification of liabilities (protecting therapy from threats such as suicidality, self-injurious behavior, lying, drug use, threats, etc.). The techniques used are clarification, confrontation and interpretation, focusing on negative affect (aggression). In the technique of interpretation, immature defense mechanisms, currently experienced object-relations dyads and their defenses are analyzed. The goal of TFP can be paraphrased as integration of the different parts of the self and the different images of others, as well as identity representation. It is also an evidence-based disorder-specific therapy [17,18].

Drug treatment options: not the first choice therapy

In clinical practice, polypharmacy is often used in borderline personality disorder, according to PD Nader Perroud, MD, University of Geneva, in his presentation on pharmacotherapy in borderline personality disorder [19]. For example, patients with borderline personality disorder receive an average of 2.7 medications daily, and approximately 50% of patients take three medications or more daily. This is surprising, especially in light of the fact that there is insufficient validated empirical evidence for medication treatment of borderline personality disorder. There are several reasons for the phenomenon of polypharmacy in patients with borderline personality disorder. On the one hand, symptoms such as emotion regulation disorders and suicidal crises pose a major challenge for treatment providers, and on the other hand, borderline personality disorders are often assigned to other diagnoses (e.g., bipolar or depressive disorders) with corresponding implications for medication (e.g., mood-stabilizing medications, antipsychotics, etc.). Approximately 40% of patients with borderline personality disorder have a misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder. Another reason for the use of pharmacotherapy is that patients often ask for medication on their own initiative to alleviate their symptoms (e.g., emotional regulation disorders, suicidal crises, etc.).

The UK guidelines (NICE guidelines [20,21]) and those of the USA (APA guidelines [22,23]) differ in their recommendations regarding pharmacotherapy. NICE guidelines advise against treating patients with borderline personality disorder with medication. An exception is made for times of crisis. In this case, medication should only be prescribed for a very short period of time (maximum one week) and should be discontinued as soon as possible. The authors of the NICE guidelines are particularly critical of the phenomenon of polypharmacy, but also mention that it is better to treat the comorbidities with medication (e.g. depressive disorders, bipolar disorders, etc.) than the borderline personality disorder as such. According to the APA Guidelines, three dimensions can be distinguished in borderline personality disorder: (a) Affective dysregulation, (b) impulsive and uncontrolled behavior, (c) cognitive-perceptual disorders. It is suggested that drug treatment be tailored to this dimensional symptomatology: (a) SSRIs (selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitors), MAO, lithium, carbamazepine, or valproate; (b) SSRIs or neuroleptics; (c) low-dose neuroleptics or antipsychotics.

Despite the difference in treatment recommendations between the two guidelines (APA vs. NICE), there is agreement on the fact that, at the current time, the empirical evidence is insufficient for a scientifically sound conclusive statement on the question of the indication of drug treatment in borderline personality disorder. The differing assessments of the two guidelines are mainly due to the fact that the NICE guidelines are more up-to-date and have incorporated more studies on the effectiveness of psychotherapeutic treatment. Based on this, the NICE guidelines concluded that psychotherapy is a better form of treatment for borderline personality disorder than pharmacotherapy. In addition, the NICE guidelines subjected conflicts of interest to critical appraisal, which was not the case in the APA guidelines. Another reason for the lack of agreement may be that, unlike the APA guidelines, the development of the NICE guidelines involved professionals from different fields (psychiatrists, psychologists, psychotherapists, pharmacologists) as well as service users. There is controversy in professional circles regarding the content of both guidelines. A meta-analysis [24] concluded that, although no clear recommendation can be derived on the basis of current data, a blanket rejection of drug treatment is too extreme and nothing speaks against symptom-specific drug treatment. Other meta-analyses on the same question reached similar conclusions. In this context, Nader Perroud, MD, points out an important guiding principle: “No evidence of an effect is not evidence of no effect.”

To summarize the assessment of medication treatment options for borderline personality disorder according to SGPP treatment recommendations:

In contrast to other disorders (e.g. schizophrenia, bipolar disorders), there is no information available for BPD that has been reviewed by Swissmedic [25] regarding the indication of drug treatment methods.

Psychotherapy should be the first-line treatment for BPD. Medication treatment strategies should only be used if for some reason there is no option for psychotherapeutic treatment.

If pharmacotherapy is used, it should be symptom specific. The current state of research does not allow a scientifically sound conclusive assessment of the indication of drug treatment in BPD. Symptom-specific use of pharmacotherapy at the lowest possible dosage is responsible, although dosage should not be increased too much.

Pharmacotherapy should be used only in times of crisis and for the shortest possible period of time. Current data do not support a conclusion about the efficacy of medication for borderline personality disorder over an extended period of time. If side effects occur, the medication should be discontinued.

* The treatment recommendations were developed in a Swiss expert panel led by Sebastian Euler, MD, and are published online.

Euler S, Dammann G, Endtner K, Leihener F, Perroud NA, Reisch T, Schmeck K, Sollberger D, Walter M, Kramer U: Treatment recommendations of the Swiss Society of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy (SGPP) for borderline personality disorder. www.psychiatrie.ch/sgpp/fachleute-und-kommissionen/behandlungsempfehlungen

An abstract is currently in the revision process at the Swiss Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry. The long version is also available in German, the French version will follow soon.

References:

- Kernberg OF, Michels R: Borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2009; 166(5): 505-508.

- Euler S: Treatment recommendations and guidelines for borderline personality disorder. Annual Congress SGPP. September 2017, Bern, CH. www.medizinonline.ch/artikel/behandlungs-empfehlungen-und-leitlinien-fuer-die-borderline-persoenlichkeitsstoerung

- Stoffers JM, et al: Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; (8). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005652.pub2

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Centre for Clinical Practice – Surveillance Program, Recommendation for Guidance Executive. Surveillance Report 2015 (6-year surveillance review). www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG78/documents/cg78-borderline-personality-disorder-bpd-surveillance-review-decision-january-20153 (Retrieved 2/15/2018).

- Falkai P, Wittchen H-U (eds.): Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5. Hogrefe 2015.

- ICD-10-GM-2018 Systematics. www.icd-code.de/icd/code/F60.3-.html. (Retrieved 2/15/2018).

- Sollberger D: Evidence-based psychotherapeutic methods for the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Annual Congress SGPP. September 2017, Bern, CH. www.medizinonline.ch/artikel/evidenzbasierte-psychotherapeutische-verfahren-zur-behandlung-der-borderline

- Working Group for Scientific Psychotherapy Freiburg. Borderline Personality Disorder. www.awp-freiburg.de/de/awp-freiburg/borderline-persoenlichkeitsstoerung.html (Retrieved 2/15/2018)

- Kramer U: General intervention principles for the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Annual Congress SGPP. September 2017, Bern, CH. www.medizinonline.ch/artikel/allgemeine-interventionsprinzipien-zur-behandlung-der-borderline-persoenlichkeitsstoerung

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR: The essential nature of borderline psychopathology. J Pers Disord 2007; 21(5): 518-535.

- Fiedler P, Herpertz SC: Personality disorders, Weinheim: Beltz 2016.

- Linehan MM: Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York NY: Guilford Press 1993.

- Young JE: Cognitive Therapy for Personality Disorders: A Schema-Focused Approach. Sarasota FL: Professional Resource Exchange 1995.

- Bateman AW, Fonagy P: The effectiveness of partial hospitalization in the treatment of borderline personality disorder – a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry 1999; 156: 1563-1569.

- Bateman AW, Fonagy P: The treatment of borderline personality disorder with psychoanalytically oriented partial hospitalization: An 18-month follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry 2001; 158: 36-42.

- Bateman AW, Fonagy P: Randomly controlled trial of outpatient mentalizing-based therapy versus structured clinical management for borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 2009; 166: 1355-1364.

- Doering S, et al: Transference-focused psychotherapy v. treatment by community psychotherapists for borderline personality disorder: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2010; 196(5): 389-95. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.070177.

- Clarkin JF, et al: Evaluating three treatments for borderline personality disorder: a multiwave study. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164(6): 922-928.

- Perroud N: Evidence-based pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder. Annual Congress SGPP. September 2017, Bern, CH. www.medizinonline.ch/artikel/evidenzbasierte-pharmakotherapie-der-borderline-persoenlichkeitsstoerung

- The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Clinical Guideline 2009. Borderline personality disorder: recognition and management. Available at www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg78. Accessed January 2018.

- The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Quality standard 2015. Personality disorders: borderline and antisocial. Available at www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs88. Accesssed January 2018.

- American Psychological Association (APA). Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry 2001; 158(Suppl10): 1-52. Available at: http://psycnet.apa.org/record/2001-18995-001. Accessed January 2018.

- Oldham JM: American Psychological Association (APA). Guideline Watch 2005: Practice Guideline For The Treatment Of Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder. Available at https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/bpd-watch.pdf. Accessed January 2018.

- Lieb K, et al: Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Cochrane systematic review of randomised trials. Br J Psychiatry 2010; 196:4-12.

- Swissmedic. Available at www.swissmedic.ch. Accessed January 2018.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2018; 16(2): 22-28.