More than 10 years ago, studies were already able to demonstrate the positive effect of endurance and strength training on fatigue symptoms in cancer patients. Since then, there have been a number of methodologically sound studies that have revealed the benefits of sports and exercise therapy interventions on fatigue at different stages of tumor treatment. But why does treating fatigue with exercise and movement work? And how can this approach be integrated into inpatient rehabilitation?

The healthy form of fatigue occurs mainly after physical and mental exertion, it is a health-protective mechanism that protects the body from overload. Fatigue caused by tumor or tumor therapy is different and presents itself in practice as pronounced fatigue, which massively restricts everyday life and quality of life on a physical and psychological level (cf. Box 1).

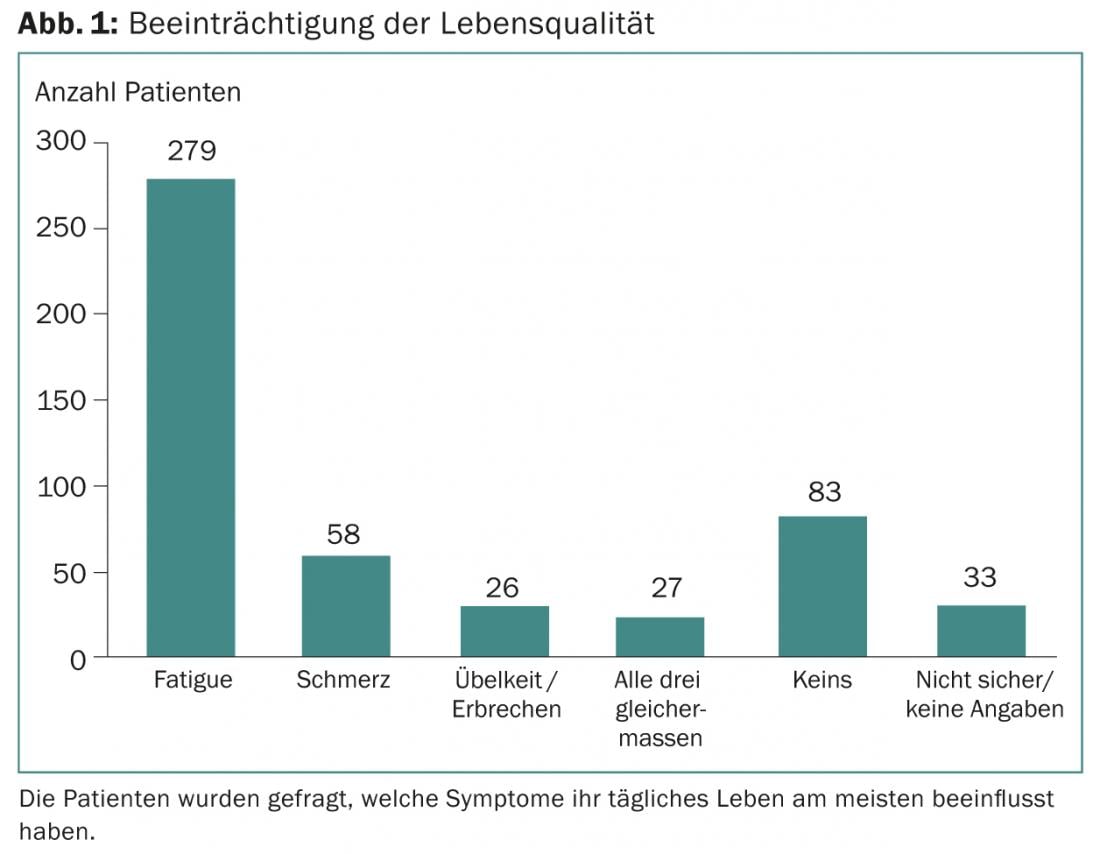

It turns out that cancer-related fatigue is still a neglected factor by various disciplines. Often, cancer therapy focuses on the treatment of pain, but for a large number of tumor patients, fatigue is the factor that most affects their quality of life, both acutely and long after tumor treatment is completed (Fig.1). In recent years, much has been done on the topic of fatigue in research and practice, but not every affected patient benefits from a multimodal treatment strategy.

Complex requirements for inpatient rehabilitation

Currently, inpatient rehabilitation in Switzerland frequently finds tumor patients with complex tumor diseases and multimorbid concomitant symptoms, often postoperatively and not infrequently with ileostoma or other physically and psychologically stressful circumstances. Therefore, the first priority is a medical course without complications. Optimal interdisciplinary communication with treating physicians, nursing, psychology as well as sports and physiotherapy also gives the patient the security of knowing that work is being done on his or her needs in a goal-oriented manner. Fatigue is only one factor among many, but from the patient’s point of view it is a crucial one.

In the meantime, validated survey methods exist [2], which can also record the symptom fatigue multidimensionally. If these are used at an early stage, inpatient rehabilitation has a decisive advantage: a multidimensional symptom can be treated in an interdisciplinary, well-networked and goal-oriented manner without any loss of time. Movement plays a crucial role in this.

How does exercise affect fatigue?

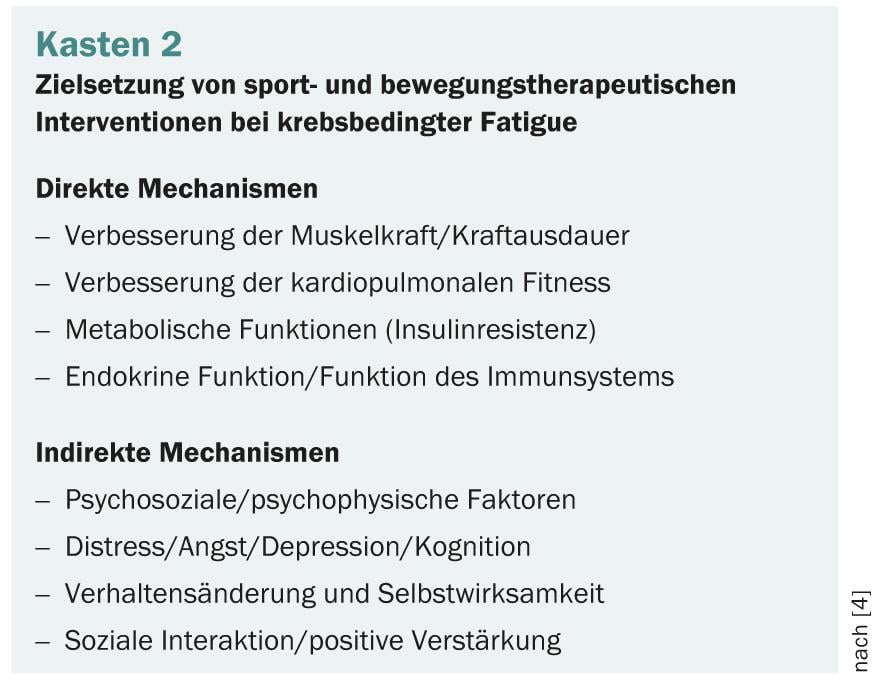

In a recent model by Wiskemann [3] explaining potential mechanisms of action of physical activity on cancer-related fatigue, the focus is on the thesis that training and exercise have a positive influence on fatigue symptoms rather indirectly: via an improvement of various psychophysical factors, such as sleep problems, depressiveness, hemoglobin levels, or functional physical status. In addition, there is a subjective improvement due to increased cardiopulmonary performance. Wiskemann’s model thus also confirms the multidimensionality of fatigue in tumor patients. However, not only physical activity is decisive for an improvement of the symptoms, but also the optimal balance between exercise and conscious relaxation as well as rest. Comparable to other internal medicine diseases, the vicious circle of immobilization should be avoided.

What can sports therapy do?

Sports therapy, which in its intention understands salutogenesis as the central starting point, must integrate itself into this multidimensionality. In addition to improving muscle function, muscle strength and cardiopulmonary performance, treatment also focuses on psychophysical factors. It is a fact that the patient’s lack of knowledge about the symptom of fatigue also leads to misunderstandings and fear of movement or stress in rehabilitation. As a result, at the beginning of a training session, trust, a basic understanding of readiness and motivation for moderate endurance and strength training, as well as already subjectively strenuous therapy sessions within rehabilitation must first be developed.

The preservation or regaining of mobility and independence as a consequence of training also has positive effects, especially psychologically and mentally, and thus also has an effect on various dimensions of fatigue via the quality of life gained. (see also Box 2). In the context of sports therapy, the patient should improve body confidence and self-efficacy, increase his or her performance and gain a sound knowledge of the relationship between exercise and fatigue: The focus here is primarily on the fact that rest and sparing do not contribute to improvement. The better informed the patient, the greater his or her ability to integrate regular physical activity or targeted training into daily life later on.

Individual training control in inpatient rehabilitation

The phases of acute treatment and follow-up, in relation to fatigue symptomatology, have been extensively studied. The phase of inpatient rehabilitation, i.e., often after direct completion of acute care, is significantly underrepresented in oncology intervention studies. Accordingly, there are no generally valid training guidelines for this phase. Recommendations by Dimeo [6] for endurance training in the range of 70-80% of maximal heart rate and strength training in the range of approximately 70% of maximal strength are still valid, but are more likely to be implemented in outpatient follow-up treatment. This is because it is often neither useful nor possible to determine maximum physical performance during the inpatient rehabilitation phase. Contraindications that generally prevent training at such an early stage were nevertheless not significantly different from other acute and chronic conditions [6] and primarily require adjustment of the amount and intensity of training. This mainly concerns thrombopenias and postoperative scars in the thorax and abdomen. Failure and overload must be avoided at all costs.

Recent studies of the Zurich High Altitude Clinic Davos [7] have shown that a total activity metabolism of 1500-2000 kcal in the first week and subsequently an increase to 2000-2500 kcal in the second and third week of rehabilitation can be implemented well and has a positive influence on fatigue symptoms. In this context, sports therapy measures and training sessions with an average volume of 30-50 min per day account for the largest share of the total turnover. Patients’ own activities, such as walking or climbing stairs, are often not yet possible in this early phase of rehabilitation and are gradually integrated into the sports and physiotherapy exercise program.

And after that?

There are still no long-term studies on the question of whether inpatient rehabilitation has significant advantages in terms of sustained and long-term improvement of fatigue symptoms. In a recent study by Kummer [7], it was demonstrated that patients with fatigue symptoms can significantly reduce fatigue in the course of early inpatient rehabilitation and can already achieve values at a level of healthy comparison persons of the same age after completion of rehabilitation. The results show that there is hope to influence fatigue already in an early interdisciplinary treatment structure. Sports therapy, integrated into this structure, has played a significant role in this. Subsequently, the treatment chain must take effect and continue the sustainability of the successes achieved at the physical and psychological level. Here, in addition to the family doctor, the oncologist also has a responsibility to provide information at an early stage when therapy begins and also to pay attention to symptoms of fatigue in the long term.

Once rehabilitation is complete, the primary care physician also has a central role in coordinating further follow-up treatment and outpatient care. In addition to comprehensive information, the “Exercise and Sport in Cancer” specialist unit and the Swiss Cancer League also offer a steadily growing network of outpatient cancer sports groups. However, as these are not yet able to meet the demand in all cantons, cancer patients in many regions are dependent on knowledge and support from the treating specialist in the acute phase and subsequently from the general practitioner.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- Educate and inform the patient about fatigue early and comprehensively

- Observe symptoms of cancer-related fatigue both during and years after completion of tumor treatment.

- Offer information brochures (e.g., “All Around Tired”/”Physical Activity with Cancer”) from the Cancer League.

- Know the possibilities and contents of inpatient oncological rehabilitation [8] and support them in case of existing rehabilitation potentials

- Motivate the patient to be physically active [9] and organize participation in outpatient cancer sports groups, for example.

- General info on sports therapy is available at www.svgs.ch.

Silvio Catuogno

Literature:

- Stone P, et al: Cancer-related fatigue: inevitable, unimportant and untreatable? Results of a multi-center patient survey. Ann Oncol 2000;11(8):971-974.

- Smets EM, et al: The Multidimensional Fatigue-Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res 1995;39(5):315-325.

- Wiskemann J, et al: Potential mechanisms of action of physical activity on fatigue symptoms in cancer patients. Paper No. 120, 42nd German Congress of Sports Physicians, Frankfurt am Main. German Journal of Sports Medicine 2011;62(7-8).

- McNeely ML, Courneya KS: Exercise programs for cancer-related fatigue: evidence and clinical guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2010;8(8):945-953.

- Baumann FT, Bloch W: Evaluated exercise interventions during and after tumor therapy – a review analysis. German Journal of Sports Medicine 2010;61(1):6-10.

- Dimeo C: Physical activity and sport in tumor diseases – moving at your own pace. In Focus Oncology 2010;5:60-66.

- Kummer F, et al: Influence of total activity in inpatient rehabilitation on Cancer-related Fatigue. Congress lecture oncoreha.ch, Fribourg, November 2011.

- Eberhard S, Buser K: Rehabilitation in oncological diseases: Principles, possibilities, requirements. Oncology 2007;3:45-48.

- Kaeding T, Frimmel M: Physical activity-based interventions in elderly cancer patients: Encouraging more physical activity. Family Practice 2011;10:48-49.

InFo Oncology & Hematology 2013; 1(1): 27-29.