Rehabilitative interventions can improve joint function and stability, build muscle strength and endurance, contribute to pain reduction and inflammation attenuation, as well as influence adaptation processes and improve (psycho)vegetative dysregulations. However, there are also limits to rehab.

If you look at the bare figures from the core documentation of the rheumatism centers in Germany, the frequency of rehabilitation measures in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) has declined significantly over the past two decades: in 1995, it was still 16.6% of all patients; in 2017, it was only 9.3% – and of these, 3.5% were outpatients. To a large extent, this is undoubtedly due to the decline in disease activity combined with a sharp increase in the quality of care. A look at the sociodemographics also underscores this: Employed male patients with RA under the age of 65 were still 47% in the workforce in 1997; by 2017, this figure had risen to 69%.

“So are our patients all so well adjusted with medication that we don’t even need rehab anymore?” asked Katrin Storck-Müller from the Rheumazentrum Mittelhessen, Bad Endbach (D), rhetorically. With these data, one might almost assume so, as disease activity by DAS28 also shows a marked decline over the past 20 years, while mean functional status (FFbH, 0-100) shows a sharp increase. However, the burden of disease remains high. Federal health reporting data from July 2017 show in our neighboring country that patients with RA still show significant functional impairment in 35% of cases, and very poor health is attested in 15.5%.

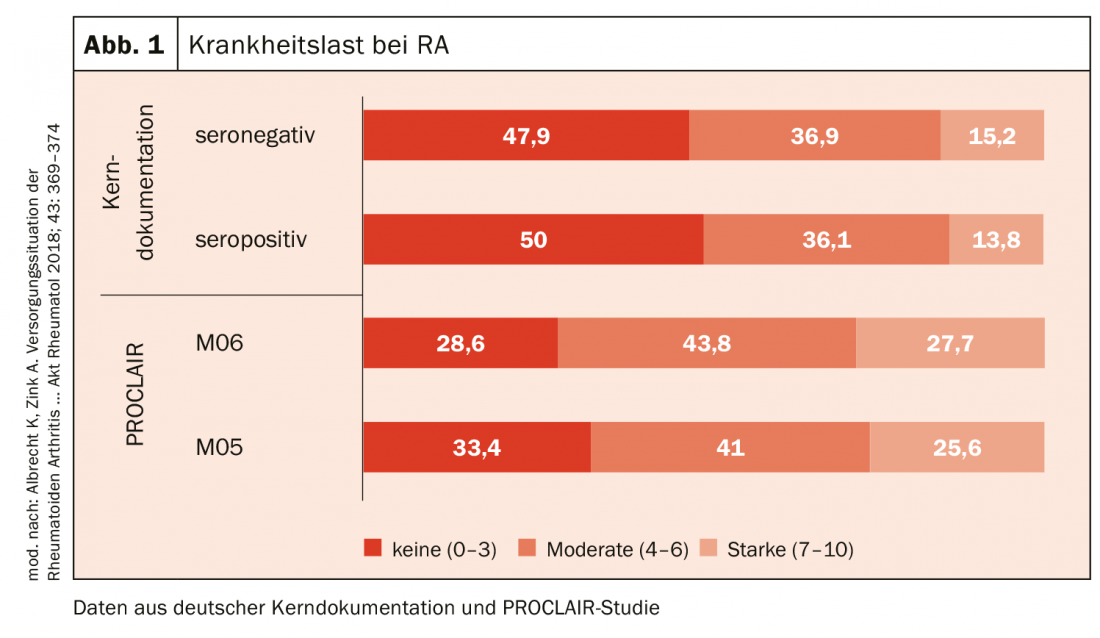

The same can be said about pain, which is a good parameter for disease burden. Again, in various registries, severe pain on the visual analog scale of 7 to 10 is still present in a large proportion of patients (Fig. 1).

Pitfalls in the application process

Thus, despite the impressive developments in pharmacological options, there is considerable need for rehabilitation. Nevertheless, long-term remission can only be achieved in a proportion of patients. Do where are the hurdles now?

The first obstacle is the application process – a problem that, according to Katrin Storck-Müller, is probably familiar to every practitioner. First of all, it is a matter of finding the right, i.e. responsible, service provider: is it the Federal Employment Agency, the statutory pension insurance, health insurance, accident insurance or perhaps social welfare agencies? An application will only be approved if there is an identifiable need, goal and potential for rehabilitation.

On the other hand, applications are rejected if, for example, there is little prospect of success of the rehabilitation measure, if the patient is not in need of rehabilitation at all, i.e. if participation in social life is not impaired by the illness (which is determined on the basis of, among other things, the rehabilitation application, the AU or the outpatient pre-treatment), or if the patient is not capable of rehabilitation, i.e. if the somatic and psychological condition of the person does not permit participation in a rehabilitation measure. This may be the case if, for example, an excessive burden of illness makes it impossible to take advantage of rehab offers and requirements. It is also very important to distinguish rehabilitation from a situation in which the patient is in acute need of treatment, i.e. when hospitalization is necessary.

With all that should not be disregarded, what can not do a rehab. Thus, it can neither replace hospital treatment nor fulfill all therapy wishes. Nor can they change individual personal and contextual factors. In addition, there is often a disagreement with the socio-medical assessment. “Sometimes patients are forced into rehab who had actually applied for a pension. Then it is very difficult to rehabilitate them sensibly and achieve a successful therapy,” Katrin Storck-Müller pointed out.

Source: 47th Congress of the German Society for Rheumatology (DGRh), Dresden (D)

InFo PAIN & GERIATRY 2019; 1(1): 40 (published 11/21/19, ahead of print).