Irritable bowel syndrome is the most common functional disorder of the gastrointestinal tract. This article provides an update on the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and therapy of this multifaceted symptom complex.

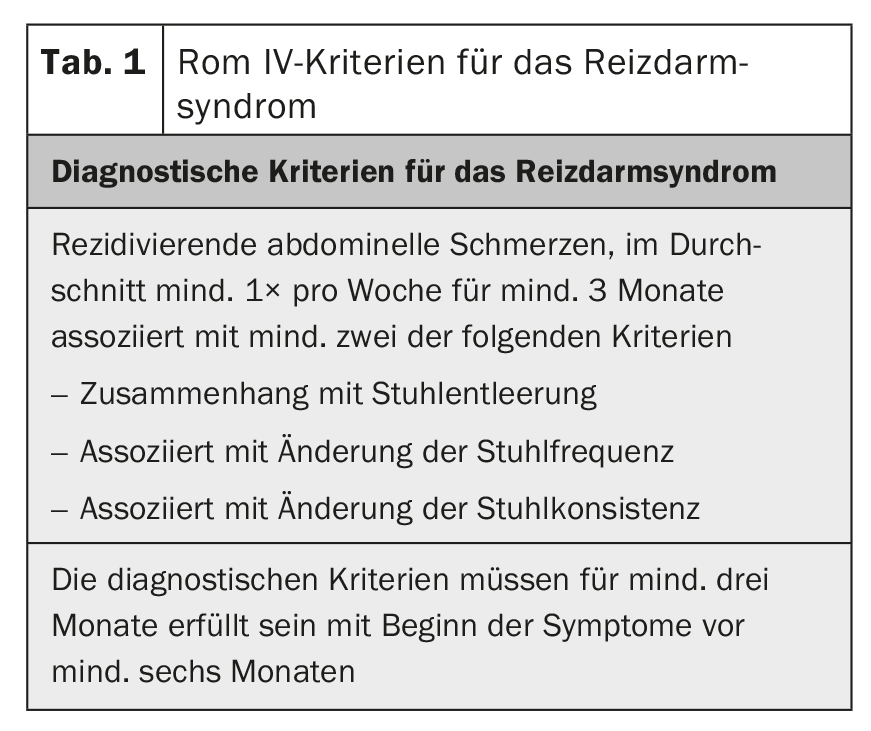

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is the most common functional disorder of the gastrointestinal tract with an estimated prevalence of 7-30% in Europe [1]. The disease represents a symptom complex described by the Rome IV criteria (Table 1) [2]. According to the stool consistency, three subtypes are described: Diarrhea-type IBS (RDS-D/IBS-D), constipation-type IBS (RDS-O/IBS-C)-R mixed-type IBS (RDS-M/IBS-M).

The diagnosis is usually made before the age of 50, and women are affected more often than men (2:1). Only a quarter of all patients seek medical treatment, which means that the number of unreported cases is high. Patients with IBS have a significantly reduced quality of life compared to the normal population, resulting in significant direct costs (physician visits, medications, comorbidities) and indirect costs (work absenteeism, reduced performance). Of the comorbidities, psychiatric disorders, especially depression, are most common in RDS patients, accounting for up to 30% as opposed to 18% in the normal population [3]. There is also a high association with conditions such as fibromyalgia, migraine and chronic fatigue syndrome.

Pathophysiology

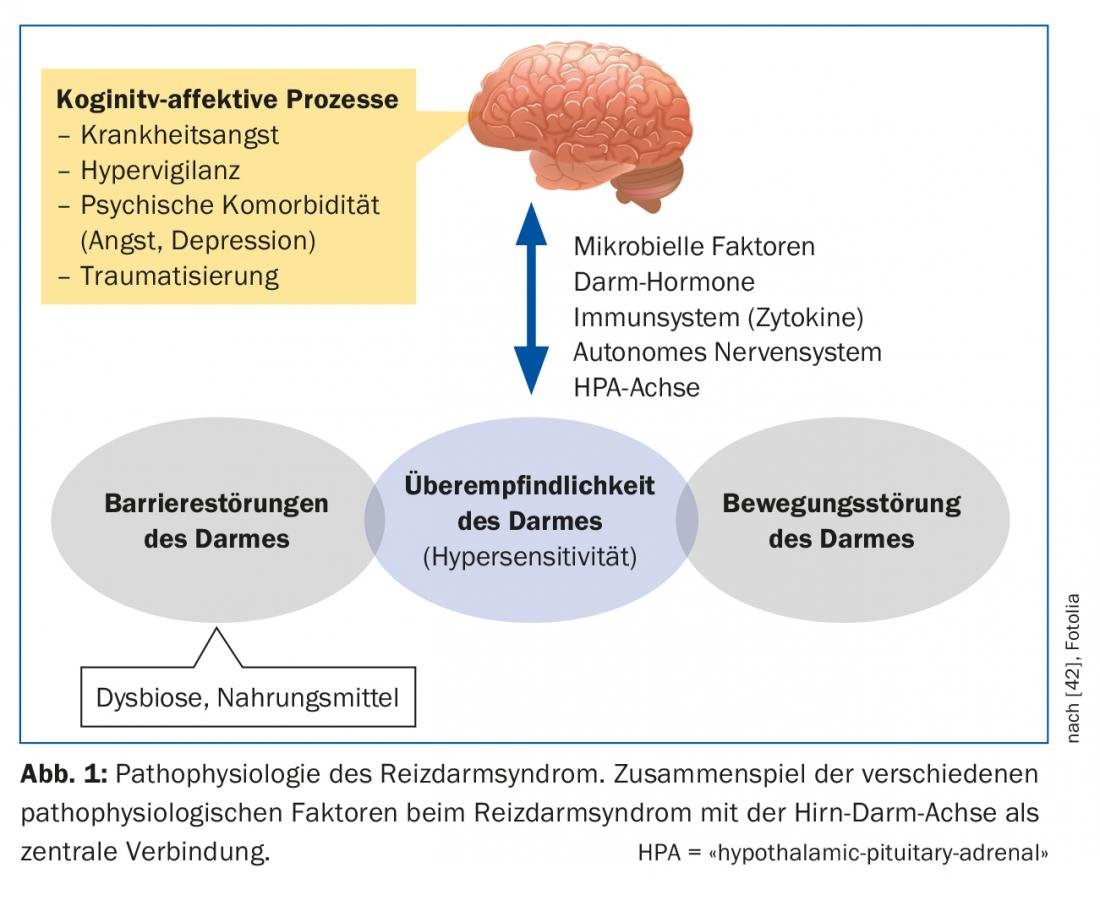

IBS is a complex multifactorial disease that is far from being understood despite numerous new findings in recent years (Fig. 1) . The brain-gut axis involves the interaction of the autonomic, neuroendocrine and neuroimmunological systems with the central nervous system. The gastrointestinal tract is highly innervated and a multitude of afferent nerve fibers generate information about the intestinal contents and regulatory processes of digestion, absorption, and immune defense [4]. In IBS, there is evidence that both the central processing of this information and the response to intestinal signals are impaired [5]. The common characteristic of functional diseases of the gastrointestinal tract is visceral hypersensitivity. IBS patients exhibit a lower perceptual and pain threshold to intestinal stimuli, which may further promote central nervous sensitization [6]. The cause of this sensitization is ultimately unclear. In IBS, subtle disturbances in gastrointestinal motility have also been reported, possibly as an effector of visceral hypersensitivity, which may result in prolonged or accelerated transit time, depending on the severity.

The mucosa of the intestine has a huge surface area with which we are in daily contact with the outside world. This interaction may be altered in multiple ways in patients with IBS. The so-called intestinal barrier consists of a singular layer of cell connections (“tight junctions”). They can increase intestinal permeability (“leaky gut”) if they do not function properly. Thus, antigens can penetrate the epithelium and trigger and maintain immunological or inflammatory processes [7]. The intestinal microbiome also plays a role here. It consists of a variety of different bacterial species and is an integral part of many intestinal barrier processes. If the natural balance is disturbed, there is intestinal dysbiosis, which can occur for various reasons (e.g. antibiotic therapy). There is evidence that quantitative and qualitative dysbiosis exists in patients with IBS, which may affect gut-brain axis function. It is also discussed whether persistent, low-grade, mucosal inflammation, e.g., after acute gastrointestinal infections, can alter intestinal permeability. In individual studies, increased inflammatory cells were found in the mucosa of RDS patients [8].

The role of chronic stress, especially after traumatic experiences in childhood, may promote the likelihood of interstinal overreaction to pain in adulthood [9]. Stress may also influence the hypothalamic cortisol axis, affecting inflammatory processes in the mucosa.

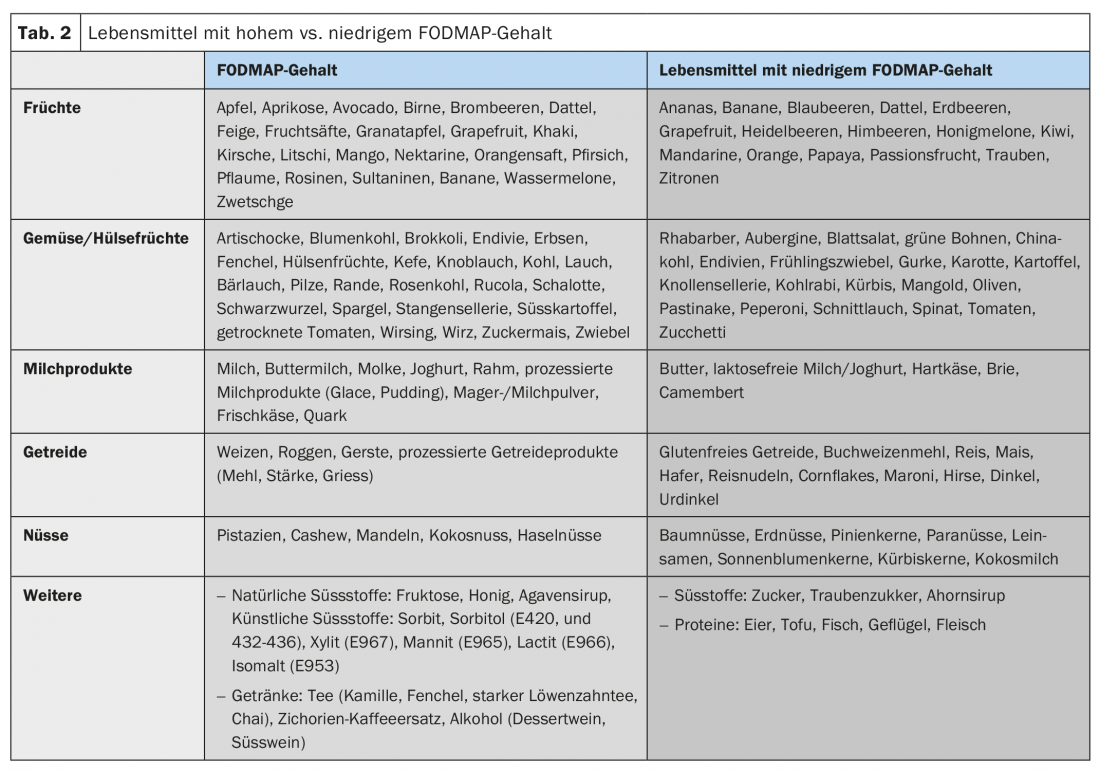

Most patients describe an increase in their symptoms after meals and most patients know which foods to avoid [10]. Due to osmotic action and bacterial fermentation, poorly absorbable food components in particular, including the so-called FODMAPs (fermentable oligo-, di- and monosaccharides and polyols), can exacerbate IBS-related abdominal symptoms (tab. 2). However, the fermentation of these FODMAPs also depends on the composition of the intestinal microbiome. In addition, direct bioactive interactions with the mucosa and immune activations by food are suspected. Cognitive factors (anticipation of pain after meals) also play a role here.

IBS runs in families, which suggests a genetic background in addition to social factors. Monozygotic twins are more likely to be affected by IBS than dizygotic twins (33% versus 13%) and a positive family history is more common in IBS than in the normal population (33% versus 2%) [11].

Diagnostics

IBS is not a diagnosis of exclusion, but can be established using the Rome IV criteria and a limited number of investigations. If no alarm signs are present – age >50 years, weight loss, fever, blood discharge ab ano, dysphagia, vomiting, fever, anemia, positive family history for colorectal tumors, inflammatory bowel disease, and celiac disease – IBS can be diagnosed with good certainty if the Rome criteria are met [12]. Only in 5% of all patients with IBS an organic disease is found in the course of the disease, but especially in the first year after the onset of IBS symptoms the exclusion of relevant systemic diseases is important [13]. After the age of 50, the likelihood of colon cancer after (presumed) RDS diagnosis is 1%, well above the normal population. In women, ovarian cancer should always be considered, as IBS-like symptoms often occur as the initial symptom [14].

In patients with RDS-D, it is recommended to serologically exclude celiac disease and determine transglutaminase IgA and total IgA antibodies. The prevalence of IgA deficiency in celiac disease is 1.7-3%, significantly higher than in the general population (0.2%). HLA-DQ2 and -DQ8 should not be used as a screening test.

be

Up to 40% of patients with inflammatory bowel disease also meet the criteria for IBS, so intestinal inflammation should be ruled out with the noninvasive and cost-effective determination of fecal calprotectin. The risk of inflammatory bowel disease with a calprotectin <40 ug/g is less than 1% [15]. The drawback is that calprotectin is not very specific, so further workup should be done if levels are elevated.

In the presence of typical IBS symptoms without alarm signs, the probability of colon cancer or inflammatory bowel disease is about 1%, so that American guidelines recommend colonoscopy only in patients older than 50 years [16]. European guidelines recommend colonoscopy in RDS-D even before 50 years of age, especially to exclude microscopic colitis [17].

In cases that remain unclear, more extensive laboratory investigations may be helpful: Systemic inflammatory markers (CRP, differential blood count), malabsorption parameters (iron status, vitamin, albumin), TSH, pancreatic elastase in stool, H2-lactose breath test, stool parasitology).

Ultrasonography in the initial evaluation of abdominal symptoms to rule out gross pathology is usually performed because it is readily available and inexpensive. However, there is no positive evidence on the benefit in IBS diagnosis.

In summary, the diagnosis of IBS is based on four factors: history, physical examination, a limited number of laboratory tests, and endoscopy in selected cases. In addition, it is worth mentioning the gynecological examination in women.

Therapy

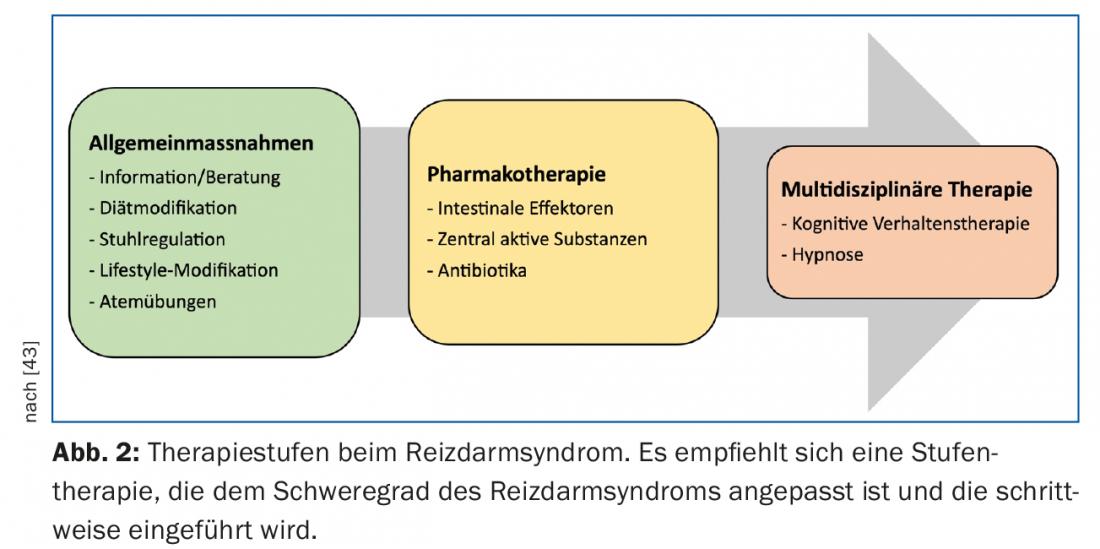

In the treatment of IBS, a stepwise approach is recommended, taking into account the severity of the symptoms described (Fig. 2) . Most patients can be successfully managed in the family practice. Only a small proportion with difficult, refractory disease benefit from the care of a specialized gastroenterology consultation.

Central to the treatment of IBS is a stable and intact doctor-patient relationship. IBS patients often complain of a lack of empathy and understanding for the symptoms they describe, which, in addition to persistent complaints, also leads to repeated consultations, demands for further clarification and, not infrequently, to regular changes of doctor. The basic therapy consists of a detailed diagnosis with a patient-oriented, comprehensible explanation of the pathophysiology and the therapeutic options without medical terminology. The authenticity of the complaints must be credibly assumed by the patient and fears must be taken seriously. It is particularly important to ask about the understanding of the disease and expectations, but at the same time realistic goals must be set (“100% diagnostic certainty is not possible”). Patients need to be involved in treatment decisions, so satisfaction/quality of life and disease progression can be positively influenced.

Diet modification: most patients report self-testing with exclusion diets in the past during the initial consultation, yet structured diet modification is often the first step in the management of IBS symptoms. Poorly absorbable, osmotically active food components, especially the so-called FODMAPs, play a role here. The efficacy of a low-FODMAP diet in IBS has been demonstrated in several studies (around 70% clinical response), so dietary modifications should always be one of the first therapeutic steps in IBS [18]. According to current data, a probationary gluten-free diet alone cannot be recommended.

Analgesic therapy: anticholinergic spasmolytics are very often used in IBS, although the evidence on the effect of these drugs is scanty [19]. In Switzerland, the following substances are mainly used: Butylscopalamine (Buscopan®), Mebeverine (Duspatalin®), Pinaverine bromide (Dicetel®), Trimebutine (Debridat®) and Metixen (Spasmocanulase®). Possible side effects may include dry mouth and visual disturbances.

Phytotherapeutics enjoy good acceptance among patients; the most commonly used in Switzerland is Iberogast®, an alcohol-based mixture of nine plant extracts. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial demonstrated significant improvement in IBS-associated abdominal pain [20]. Peppermint oil capsules (Colpermin®), which are often used, have also been shown to significantly reduce IBS symptoms [21,22]. Here, the effect is probably multifactorial, including antagonizing action at calcium channels (muscle relaxation) and agonizing action at opioid receptors. Another preparation is the artichoke concentrate Hepa-S®, but here the limited data show no definite benefit [23].

Antidepressants such as serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants aim to correct a serotonergic deficit acting on the gut-brain axis. In a Cochrane Review [24] positive effects on general well-being as well as specifically on abdominal complaints could be achieved (number needed to treat (NNT) = 4 resp. 5). However, IBS patients without depression as a comorbidity do not seem to benefit from therapy with SSRIs.

Treatment of IBS with constipation: the use of swelling agents such as Sterculia (Colosan®, Normacol®) and psyllium/flaxseed (Metamucil®, Mucilar®, Linomed®) or isoosmotic polyethylene glycol-based laxatives (Transipeg®, Movicol®) can improve stool frequency and consistency, but these preparations have no effect on IBS-associated abdominal pain or flatulence [19]. Stimulant laxatives should be avoided because of poor tolerance.

Linaclotide (Constella®) is a guanylate cyclase agonist acting locally in the intestine that is approved for the treatment of IBS with constipation. Local receptor action leads to the activation of ion channels in the intestine, resulting in the secretion of chloride, bicarbonate and water into the intestinal lumen. In addition, there is also an analgesic effect on nociceptors of the intestine. Linaclotide significantly increases the number of complete defecations and reduces the number and severity of abdominal pain [25,26].

Lubiprostone (Amitiza®) is a local intestinal chloride channel activator approved in Switzerland for the treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation and opioid-induced constipation. In lower dosage, the drug is also approved in the US and Japan for IBS-O where it showed good in IBS symptoms (pain, bloating) [27].

Prucalopride (Resolor®) is a selective, high-affinity serotonin (5-HT4) receptor agonist approved in Switzerland for the treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation. There are data for use in RDS-O that have shown a positive effect on RDS symptoms [28].

Treatment of IBS with diarrhea: Loperamide (Imodium®) is often used in IBS-D to regulate stool, but has no effect on pain symptoms. In combination with a swelling agent, the anti-diarrheal effect can be improved. In addition, the bile acid binder cholestyramine (Quantalan®) can be used on a trial basis to treat diarrhea, as approximately 25% of all IBS-D patients show evidence of bile acid wasting syndrome [29]. In nonrandomized studies, cholestyramine has been shown to reduce stool frequency and abdominal discomfort [30].

Eluxadoline (Truberzi®) is a local intestinal agonist of μ-opioid and κ-opioid receptors and antagonist of δ-opioid receptors and thus has anti-diarrheal and analgesic properties. In February 2018, the drug was approved by Swissmedic for the treatment of IBS-D, but it is not yet available in Switzerland. In a randomized trial, Truberzi demonstrated better pain and diarrhea control than placebo after 12 weeks of therapy over the subsequent 1-year period [31]. This was also true for patients who had been previously treated with the μ-opioid receptor loperamide [32].

Ondansetron (Zofran®) is a serotonin (5-HT3) receptor antagonist approved in Switzerland for the treatment of chemotherapy-associated nausea. In IBS-D patients, a slowing of intestinal peristalsis and a reduction in visceral hypersensitivity or abdominal pain were also observed [33]. Further studies are planned to confirm these promising results.

Rifaximin (Xifaxan®) is an intestinal-specific antibiotic approved in Switzerland for the prevention of relapses in hepatic encephalopathy. In the USA, the drug can also be used for the treatment of RDS-D. For rifaximin, it was shown that after two weeks of therapy, there was a positive effect on IBS symptoms for the next ten weeks (8-10% more frequent versus placebo) [34]. Antibiotic therapy appears to result in a positive change in the intestinal microbiome, but the exact mechanisms are unclear. If necessary, the therapy cycle can be repeated as desired. Initial concerns about the development of resistance have not been confirmed, and the side effect profile is low.

For the use of probiotics, the evidence in IBS is not conclusive; studies are heterogeneous, with positive results in majority of smaller studies. Lactobacillus spec, Bifidobacterius spec, and Saccharomyces boulardii appear to have the best results. In a recent systematic review, probiotics were found to be effective in certain irritable bowel patients [35].

Nonpharmacologic therapies: For cognitive behavioral therapy and hypnosis, there appears to be some benefit in IBS treatment; however, it remains unclear whether the improvement in IBS symptoms is related to an effective reduction in visceral pain or simply reflects better pain processing. Two Cochrane analyses in 2009 were cautious about the effect of these therapies [36,37]. In a recent systematic review, the effect of these therapies was positively assessed, but the form of contact, duration of treatment, and type of communication remain ill-defined [38].

Treatment of IBS with bloating symptoms: Bloating with or without visible abdominal girth gain is a feature of various functional gastrointestinal disorders and is often found to be very bothersome by patients. Besides dietary modifications (low FODMAP diet) and the use of rifaximin, there are few therapeutic options. There is no evidence for the use of defoaming agents such as simethicone (Flatulex®) or dimethicone (Spasmocanulase®) in functionally related bloating symptoms. Their usefulness is then also mostly disappointing. A number of elegant studies have demonstrated that bloating in IBS patients is not caused by an increase in intestinal gas volume but by caudo-ventral shifts of intra-abdominal contents. Rather, due to a viscero-somatic reflex, there is an abnormal muscular response of the diaphragm (contraction) and lower abdominal muscles (relaxation), resulting in protrusion of the abdomen [39]. The same research group was then able to achieve a significant reduction in symptoms and also abdominal girth in IBS patients with acute bloating symptoms using biofeedback-assisted specific breathing therapy [40]. In a subsequent randomized trial, bloating symptoms continued to decrease with regular exercise over a six-month observation period [41].

Summary

IBS remains a symptom complex that is only beginning to be understood, and treatment options are still limited. As our understanding of pathophysiology increases, it is likely that we will be able to characterize additional subtypes in what is now a very heterogeneous pot of functional bowel diseases. Not on the basis of clinical symptoms, as the Rome IV criteria attempt to do today, but with the help of biomarkers, which in the future may allow a positive diagnosis of this clinical picture. A better understanding of the pathophysiology would then inevitably lead to the development of new therapeutic approaches that go beyond today’s purely symptom-oriented treatment.

Take-Home Messages

- Irritable bowel syndrome is not a diagnosis of exclusion, but can be established using the Rome IV criteria and a limited number of investigations.

- Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome is based on a stepwise approach, taking into account the severity.

- Dietary modifications, especially a FODMAP (fermentable oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides), and a diet low in polyols should be one of the first therapeutic steps.

- Functional bloating symptoms can be relieved with physical and respiratory therapy.

Literature:

- Saha L: Irritable bowel syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, and evidence-based medicine. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(22): 6759-6773.

- Lacy BE, et al: Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2016; 150(6): 1393-1407e5.

- Grundmann O, Yoon SL: Irritable bowel syndrome: Epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment: An update for health-care practitioners. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 25(4): 691-699.

- Brookes SJH, Spencer NJ, Costa M, Zagorodnyuk VP: Extrinsic primary afferent signalling in the gut. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 10(5): 286-296.

- Lee YJ, Park KS: Irritable bowel syndrome: Emerging paradigm in pathophysiology. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(10): 2456-2469.

- Soares RLS: Irritable bowel syndrome: A clinical review. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(34): 12144-12160.

- Matricon J, et al.: Review article: Associations between immune activation, intestinal permeability and the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012; 36(11-12): 1009-1031.

- Katiraei P, Bultron G: Need for a comprehensive medical approach to the neuro-immuno-gastroenterology of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(23): 2791-27800.

- Larauche M, Mulak A, Taché Y: Stress-related alterations of visceral sensation: animal models for irritable bowel syndrome study. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011; 17(3): 213-234.

- Heizer WD, Southern S, McGovern S: The Role of Diet in Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Adults: A Narrative Review. J Am Diet Assoc 2009; 109(7): 1204-1214.

- El-Salhy M: Irritable bowel syndrome: Diagnosis and pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(37): 5151-5163.

- Whitehead WE, Palsson OS, Simrén M: Irritable bowel syndrome: what do the new Rome IV diagnostic guidelines mean for patient management? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 11(4): 281-283.

- El-Serag HB, Pilgrim P, Schoenfeld P: Systematic review: Natural history of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004; 19(8): 861-870.

- Hamilton W, Peters TJ, Bankhead C, Sharp D: Risk of ovarian cancer in women with symptoms in primary care: population based case-control study. BMJ 2009; 339(7721): 616.

- Menees SB, et al: A meta-analysis of the utility of C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, fecal calprotectin, and fecal lactoferrin to exclude inflammatory bowel disease in adults with IBS. Am J Gastroenterol 2015; 110(3): 444-454.

- AGA: American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement: Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenerology 2002; 123(6): 2105-2107.

- Layer P, et al: S3 Guideline Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Definition, Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Therapy. Joint guideline of the German Society for Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (DGVS) and the German Society for Neurogastroenterology and Motility. Journal of Gastroenterol 2011; 49(2): 237-293.

- Halmos EP, et al: A Diet Low in FODMAPs Reduces Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterology 2014; 146(1): 67-75.

- Ruepert L, et al: Bulking agents, antispasmodic and antidepressant medication for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; (8): CD003460.

- Madisch A, Holtmann G, Plein K, Hotz J: Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with herbal preparations: Results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multi-center trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004; 19(3): 271-279.

- Merat S, et al: The effect of enteric-coated, delayed-release peppermint oil on irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci 2010; 55(5): 1385-1390.

- Khanna R, MacDonald JK, Levesque BG: Peppermint oil for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2014; 48(6): 505-512.

- Liu J, et al: Herbal medicines for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; (1): CD004116.

- Kaminski A, et al: Antidepressants for the treatment of abdominal pain-related functional gastrointestinal disorders in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; (7): CD008013.

- Chey WD, et al: Linaclotide for Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Constipation: A 26-Week, Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial to Evaluate Efficacy and Safety. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107(11): 1702-1712.

- Rao S, et al: A 12-week, randomized, controlled trial with a 4-week randomized withdrawal period to evaluate the efficacy and safety of linaclotide in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107(11): 1714-1724.

- Drossman DA, et al: Clinical trial: Lubiprostone in patients with constipation-associated irritable bowel syndrome – Results of two randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009; 29(3): 329-341.

- Malagelada C, et al: Effect of prucalopride on intestinal gas tolerance in patients with functional bowel disorders and constipation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 32(8): 1457-1462.

- Wedlake L, et al: Systematic review: The prevalence of idiopathic bile acid malabsorption as diagnosed by SeHCAT scanning in patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009; 30(7): 707-717.

- Camilleri M: Management Options for Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc 2018; 93(12): 1858-1872.

- Lembo AJ, et al: Eluxadoline for Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Diarrhea. N Engl J Med 2016; 374(3): 242-253.

- Lacy BE, et al: Eluxadoline Efficacy in IBS-D Patients Who Report Prior Loperamide Use. Am J Gastroenterol 2017; 112(6): 924-932.

- Garsed K, et al: A randomised trial of ondansetron for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea. Gut 2014; 63(10): 1617-1625.

- Pimentel M, et al: Rifaximin Therapy for Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome without Constipation. N Engl J Med 2011; 364(1): 22-32.

- Hungin APS, et al: Systematic review: probiotics in the management of lower gastrointestinal symptoms in clinical practice — an evidence-based international guide. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013; 38(8): 864-886.

- Webb AN, Kukuruzovic RH, Catto-Smith AG, Sawyer SM: Hypnotherapy for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane database Syst Rev 2007; (4): CD005110.

- Zijdenbos IL, et al: Psychological treatments for the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; (1): CD006442.

- Radziwon CD, Lackner JM: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for IBS: How Useful, How Often, and How Does It Work? Curr Gastroenterol 2017; 19(10): 49.

- Accarino A, et al: Abdominal Distention Results From Caudo-ventral Redistribution of Contents. Gastroenterology 2009; 136(5): 1544-1551.

- Barba E, et al: Abdominothoracic mechanisms of functional abdominal distension and correction by biofeedback. Gastroenterology 2015; 148(4): 732-739.

- Barba E, Accarino A, Azpiroz F: Correction of Abdominal Distention by Biofeedback-Guided Control of Abdominothoracic Muscular Activity in a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 15(12): 1922-1929.

- Van Oudenhove LV, et al: Biopsychoscial aspects of functional gastrointestinal disorders: how central and environmental processes contribute to the development and expression of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology 2016; 150(6): 1355-1367.e2.

- Jaynk GS, Gyawali CP: Irritable bowel syndrome: Modern concepts and management options. The American journal of Medicine 2015; 128(8): 817-827.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2019; 14(1): 11-18