For the first time after the highly acclaimed FOURIER trial, a PCSK9 inhibitor now also shows a mortality benefit in secondary prevention. The product in question is alirocumab. Experts are reacting positively and are already discussing lowering the target values.

Brief review: The 2017 ACC Congress was dominated by the FOURIER trial, which for the first time provided data on the long-awaited (and strongly requested) “hard” endpoints in PCSK9 inhibition. The addition of evolocumab significantly decreased the risk of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization. Evolocumab was also superior to placebo in the secondary endpoint, which included only cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke (added to existing statin therapy with/without ezetimibe) – specifically, the risk was reduced by a significant 20%. This with a good safety profile. The hypothesis “the lower, the better” seemed to be confirmed, but the big question was: Are the results sufficient to justify the not insignificant drug prices of the active substance class and to use the drugs on a broader(er) front?

Finally – and this was a crucial but – the morbidity benefit did not translate into a significant survival benefit. Although it is known from other studies comparing more intensive with moderate lipid-lowering therapy that additional LDL cholesterol lowering does not always exert a significant effect on cardiovascular mortality. Alternatively, the full clinical benefit may only become apparent after a certain delay (FOURIER was relatively short, lasting about two years).

In everyday clinical practice, however, certain question marks and limitations remained in the use of the new, expensive class of active ingredients, and the first results of the competitor alirocumab were awaited with all the more anticipation.

ODYSSEY OUTCOMES

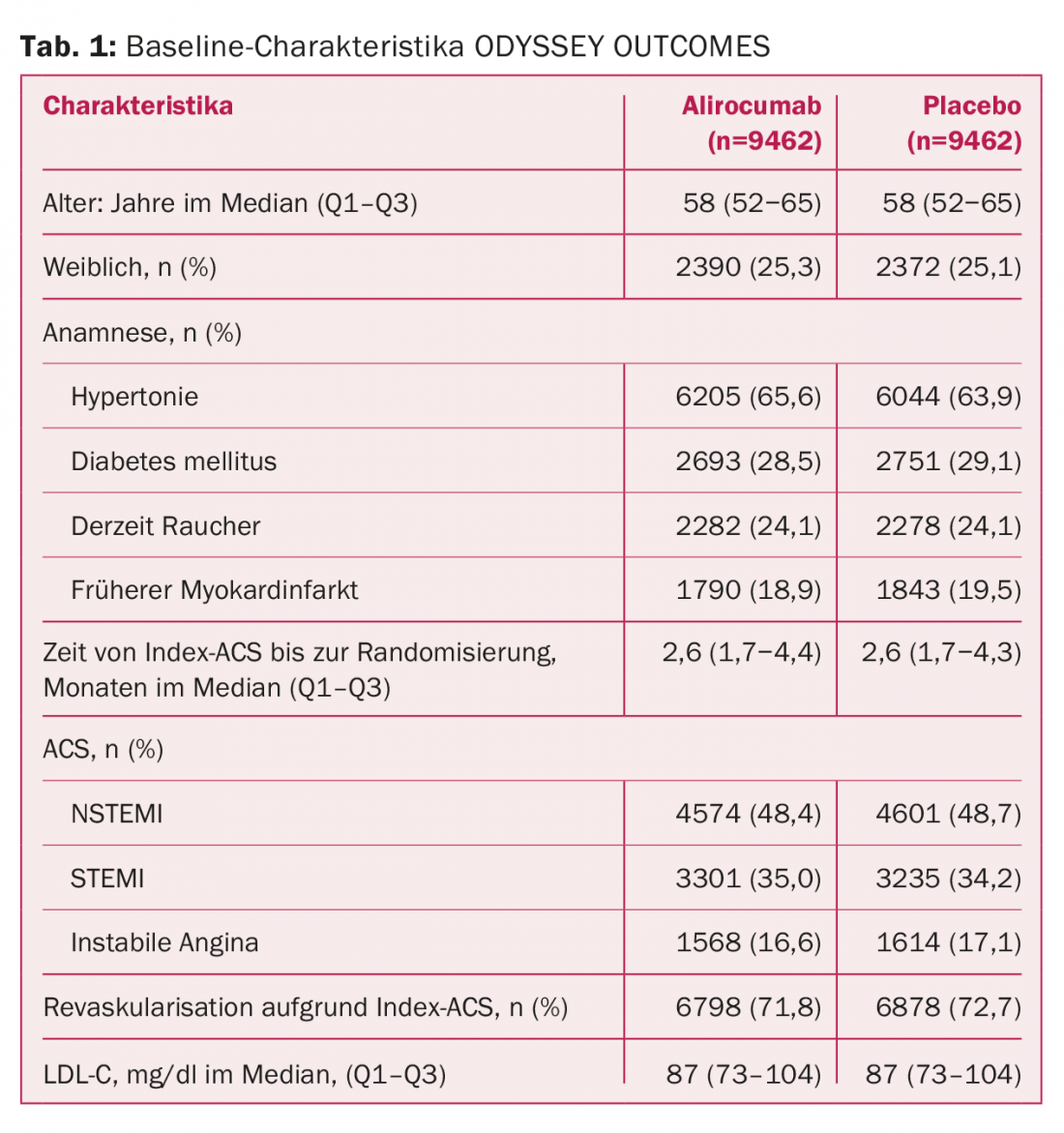

Now they are here, in the form of the ODYSSEY OUTCOMES study. And even they do not clarify all open points regarding PCSK9 therapy with absolute certainty. This is due, on the one hand, to the deviating study population selected. Instead of just over 27 000 patients with stable established atherosclerotic disease as in FOURIER, here there were almost 19 000 patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in the last 1-12 months and inadequate lipid control, ie, LDL-C values ≥1.8 mmol/l despite high-intensity or maximally tolerated statin therapy. 89% were on high-dose atorvastatin/rosuvastatin at baseline, and 3% received ezetimibe. A sample with clearly increased risk for further events (Tab. 1). In FOURIER, a minority of patients had an ACS in the previous year.

The drug, taken every two weeks, reduced the risk of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) by a significant 15% compared with placebo. These included death from CHD, nonfatal myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, or unstable angina with hospitalization. This is the next difference from FOURIER, in which the “softer” component of coronary revascularization was also still included in the primary end point. The hurdle to generating a significant advantage is therefore likely to have been somewhat higher this time. Follow-up lasted a median of 2.8 years.

The rate of separately considered myocardial infarction and (this time also) all-cause mortality were equally improved, the former from 7.6% to 6.6% (p=0.006) and the latter from 4.1% to 3.5% (p=0.026, 15% reduction). When death due to CHD and cardiovascular death were considered separately – also secondary endpoints – no significant differences were found. Whereby it has to be said that in a global study in 1315 centers and 57 countries, it cannot necessarily be ensured that the causes of death are always correctly documented insofar as patients die at home. Death itself, on the other hand, can be determined with certainty everywhere. The p-value of 0.026 in all-cause mortality is considered “nominal” because this endpoint was statistically evaluated downstream (hierarchical endpoint evaluation).

Patients tolerated treatment well with comparable rates of adverse events (including severe). There were also no relevant differences in new-onset diabetes, allergic reactions, or neurocognitive events (if anything, the agent tended to be superior to placebo). After more than three years of treatment in this large collective, no safety signal was found with alirocumab apart from injection site reactions.

The deeper the better

Like FOURIER, ODYSSEY OUTCOMES argues for the “lower is better” hypothesis and thus for adjusting therapy according to lipid levels (rather than basing it solely on statin intensity, see guideline controversy of recent years between the United States and Europe). However, it also suggests that in CHD, the current target LDL cholesterol levels of less than 70 mg/dl are not yet optimal.

At baseline, LDL-C was 87 mg/dl. Over 50% LDL-C reductions were rapidly observed and predominantly persisted during follow-up. The reductions were qualitatively comparable to those from FOURIER: after four months on alirocumab, LDL-C was 37.6 mg/dl, compared with 93.3 mg/dl on placebo, a reduction of more than 60 percent. Exceptionally clear values, which one is now accustomed to from PCSK9 inhibition.

One has to wonder: will the increasing success of PCSK9 inhibition soon create a new standard, namely LDL lowering below 50 mg/dl? Finally, the dimension of clinical improvement in the primary endpoint (and most especially at high baseline LDL levels) is remarkable. And after FOURIER, ODYSSEY OUTCOMES is the second large study to demonstrate that lowering LDL cholesterol to a range of 25-50 mg/dl improves the prognosis of CHD patients.

At the end of follow-up after 48 months, levels were still 53.3 vs. 101.4 mg/dl (reduction of 54.7%). The goal of the study was an LDL-C of 25-50 mg/dl; active efforts (and blinded titration) were made to keep as many patients as possible within this target range. Thus, it is unclear whether the long-term reduction in LDL-C lowering was related to the study design (dose was adjusted or switched to placebo at levels below the target range) or to the development of neutralizing antibodies to the drug, which appeared to occur more frequently in the treatment group (42 vs. 6 cases). Studies from another trial program called SPIRE [1,2] with the PCSK9 antibody bococizumab were stopped early, among other reasons, precisely because of this problem: Apparently, the LDL-lowering effect decreased significantly due to antibody formation. Only patients with baseline LDL-C above 2.6 mmol/l benefited in SPIRE 1 and 2. With Evolocumab resp. in FOURIER the problem did not show up. According to the authors of ODYSSEY OUTCOMES, alirocumab is also not expected to have an adverse effect due to the antibodies.

Who benefits the most?

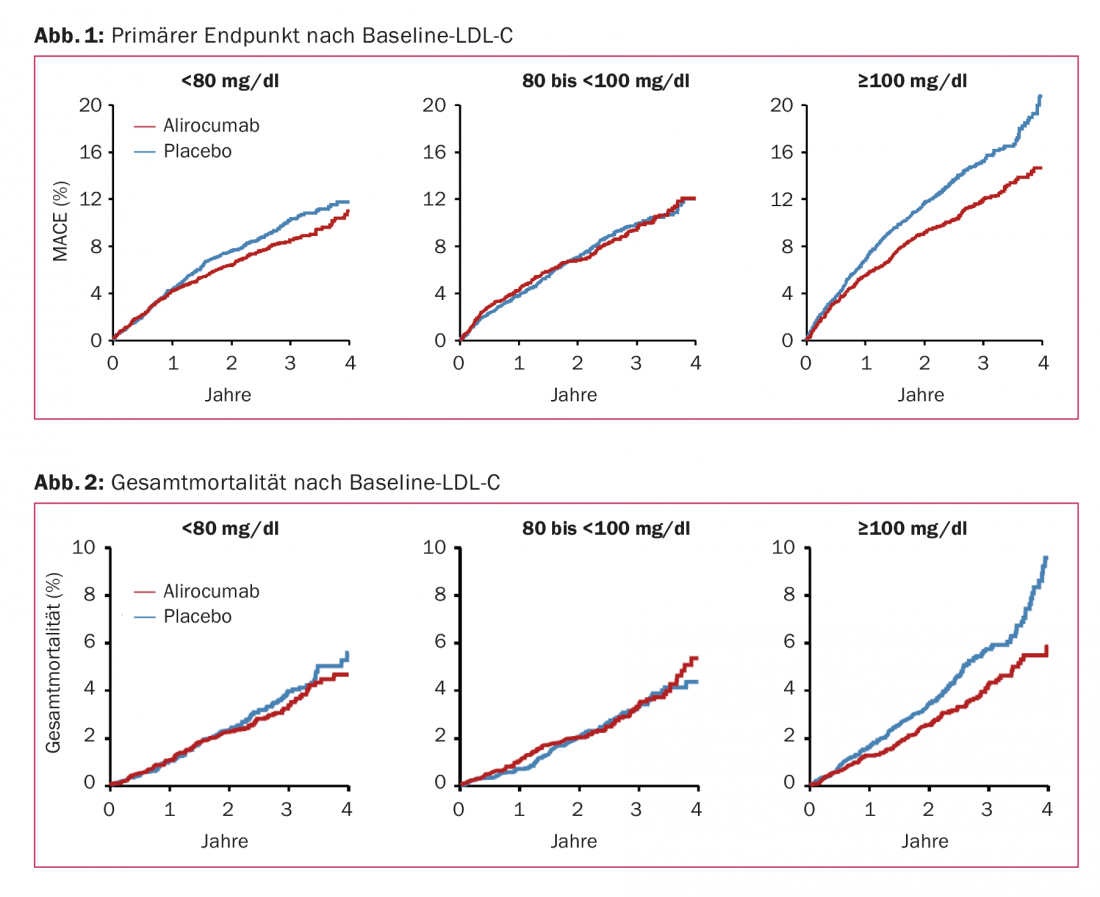

Consequently, the calls for cost-benefit analyses of PCSK9 inhibitors did not go away even after ODYSSEY OUTCOMES, which was received positively overall. Previous evaluations drew a negative conclusion [3,4]. Either the price would have to be changed or those patients would have to be defined more precisely for whom the benefits clearly outweighed the costs, as was heard on several occasions at the congress. More pressure on insurers to reimburse the drug class more broadly was also called for. Subgroup analyses from ODYSSEY OUTCOMES suggest that patients with LDL-C ≥100 mg/dl at baseline (median 118 mg/dl) benefit particularly. Among them, MACE reduces from 14.9% to 11.5% (HR 0.76) and all-cause mortality from 5.7% to 4.1% (HR 0.71). Similar risk reductions were also found in this subgroup for deaths due to CHD and cardiovascular death. However: there was no significant interaction between primary outcomes or all-cause mortality and baseline LDL-C levels (p=0.09 and p=0.12, respectively). Even the group with baseline LDL-C <80 mg/dl still experienced a risk reduction of 14% in the primary endpoint and 11% in all-cause mortality with the agent (Figs. 1 and 2).

Overall, the post-ACS population in ODYSSEY OUTCOMES was nonetheless higher in risk than the FOURIER sample. Indeed, despite evidence-based preventive strategies, residual risk remains high shortly after ACS and is related, in part at least, to LDL-C levels. If these are lowered early after the event, e.g., by statin therapy [5] – especially high-intensity [6] or in combination with ezetimibe [7] – the risk of further events is also reduced (side note: Whether the principle “the earlier statins in ACS, the better” applies here was questioned by the SECURE-PCI trial, also at ACC 18). Apparently, the protective effect can be further enhanced with potent PCSK9 inhibition. So perhaps it is indeed mainly this high-risk group that benefits from PCSK9 inhibition not only in terms of morbidity but also in terms of mortality, which would better support the high drug prices. In addition to the different study population, the extended follow-up time may have played a role in the improved survival.

In any case, after the two positive studies FOURIER and ODYSSEY OUTCOMES, a solution must now also be found in terms of costs in order to finally be able to give the active substance to all patients who would benefit from it (which, according to current evidence, are many). Finally, safety, which is generally also on the “cost” side of the cost/benefit profile, is so good in the case of PCSK9 inhibition that the pendulum would clearly swing to the “benefit” side – if drug prices were disregarded.

What is clear is that ODYSSEY OUTCOMES provides the next piece of the puzzle in an overall picture that is becoming increasingly clear for this relatively new class of agents. According to the current study situation, evolocumab is considered for patients with stable atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and alirocumab for patients in the ACS setting – this until further notice, until a class effect is confirmed.

Alirocumab is currently approved concomitantly with diet and in addition to a maximum tolerated statin dose with or without other lipid-modifying therapies for the treatment of adults with severe heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia or with clinically manifest atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease who require additional LDL-C lowering. According to Limitatio, its use in secondary prevention is currently limited to patients with LDL-C >3.5 mmol/l and/or progressive clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease with an LDL-C >2.6 mmol/l.

Source: American College of Cardiology (ACC) 2018 Annual Scientific Session, March 10-12, 2018, Orlando.

Literature:

- Ridker PM, et al: Cardiovascular Efficacy and Safety of Bococizumab in High-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 1527-1539.

- Ridker PM, et al: Lipid-Reduction Variability and Antidrug-Antibody Formation with Bococizumab. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 1517-1526.

- Kazi DS, et al: Updated Cost-effectiveness Analysis of PCSK9 Inhibitors Based on the Results of the FOURIER Trial. JAMA 2017; 318(8): 748-750.

- Fonarow GC, et al: Cost-effectiveness of Evolocumab Therapy for Reducing Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. JAMA Cardiol 2017; 2(10): 1069-1078.

- Schwartz GG, et al: Effects of atorvastatin on early recurrent ischemic events in acute coronary syndromes: the MIRACL study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001 Apr 4; 285(13): 1711-1718.

- Cannon CP, et al: Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2004 Apr 8; 350(15): 1495-1504.

- Cannon CP, et al: Ezetimibe Added to Statin Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndromes. N Engl J Med 2015 Jun 18; 372(25): 2387-2397.

CARDIOVASC 2018; 17(2): 35-38