Diagnosis, therapy and follow-up of testicular cancer are clearly defined by international consensus recommendations. The chances of curing testicular cancer are high with adequate treatment. Patients with testicular cancer should present to a specialized oncology center.

Testicular cancer, although rare with an incidence of about 10/100,000 population, is the most common cancer in the 15- to 40-year-old male age group. In about 3% there is also a precancerous lesion on the contralateral, non-tumor-bearing testis (CIS or TIN or IGCNU) , in about 5% testicular cancer occurs primarily extragonadally (so-called extragonadal germ cell tumors). Therefore, the differential diagnosis of testicular tumor or germ cell tumor must be included in all men with unclear primary tumor [1]. Due to the unusually good response to therapy and thanks to consistently conducted studies, testicular cancer became a kind of “model disease” to describe successful oncological action quite early on.

Diagnostics, staging and risk stratification

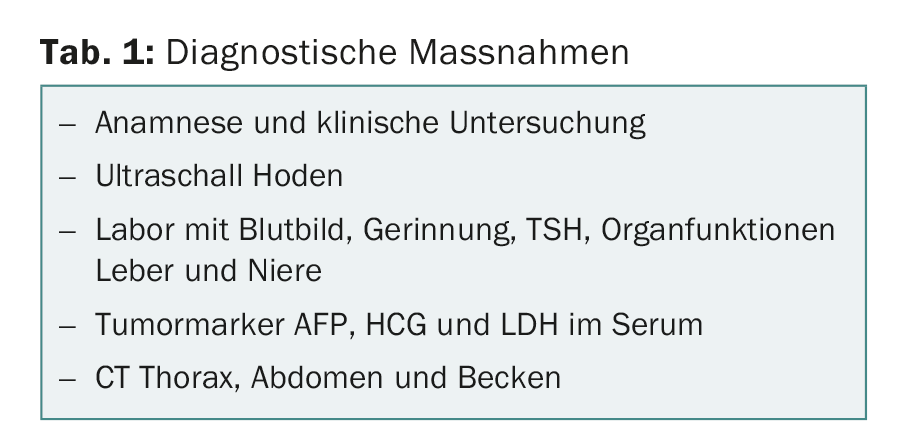

Primary diagnosis of testicular cancer first involves the steps shown in Table 1. CT or MRI of the head is required only if pulmonary metastases are detected or if clinical symptoms are present. PET-CT has no role in the primary diagnosis of testicular cancer [1].

Regarding histology, the distinction between seminomas, non-seminomas and mature teratomas is important. All mixed tumors and all tumors from patients with AFP elevation are considered non-seminomas regardless of histology. In staging, a distinction is made in routine clinical practice between a stage I, with disease confined to the testis, and metastatic tumor stages. In patients with clear elevation of tumor markers AFP and HCG, histologic confirmation is not required even for extragonadal germ cell tumors.

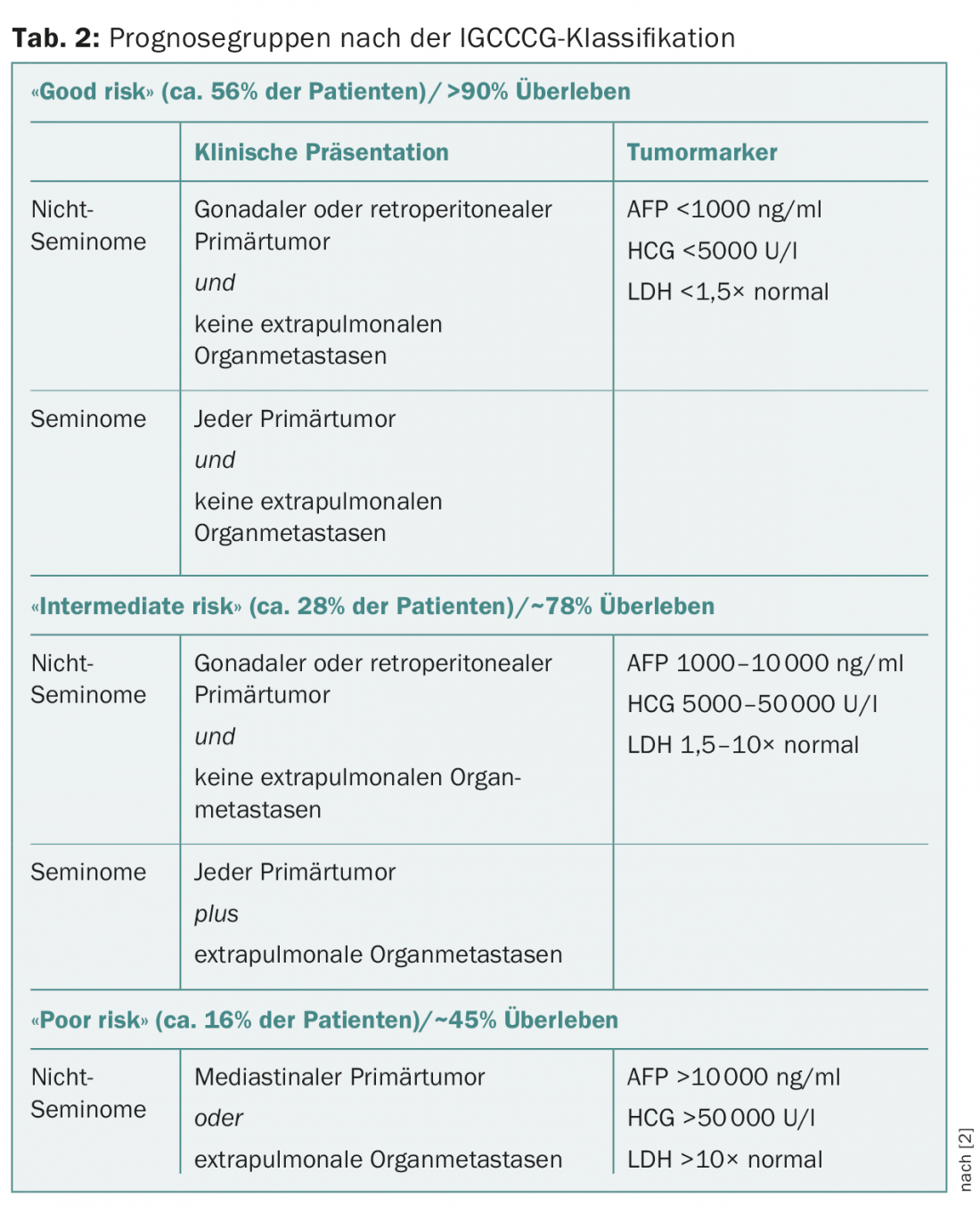

In clinical stage I with disease confined to the testis, tumor size, infiltration of the rete testis, and more recently lymphovascular vascular invasion in the primary tumor are discussed as risk factors for occult metastasis in seminomas but are controversial. In stage I non-seminomas, lymphovascular vascular invasion in the primary tumor has been confirmed as a risk factor for occult metastasis, but the significance of infiltration of the rete testis or the percentage of embryonal carcinoma is controversial. Metastatic tumor stages are divided into three prognostic groups according to the IGCCCG (International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group) classification (Table 2) [2].

Primary therapy

Patients with gonadal disease primarily receive orchiectomy. Biopsy of the contralateral unaffected testis is useful for identifying patients with CIS or TIN or IGCNU but remains optional. In contrast, patients with widely metastatic disease and gonadal primary tumor receive chemotherapy primarily and orchiectomy only after completion of chemotherapy.

Stage I therapy

Patients with stage I seminoma receive active surveillance as standard with a recurrence risk between 10-25%. Adjuvant therapy with one cycle of carboplatin at an AUC 7 dose can reduce the risk of recurrence to 5%, but is overtherapy for the majority of patients. Adjuvant paraaortic radiotherapy with 20 Gy is reserved for individual cases.

Patients with stage I non-seminomas without lymphovascular invasion in the primary tumor receive active surveillance as standard with a recurrence risk of approximately 15%. One cycle of adjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin, etoposide, and bleomycin (PEB) can reduce the risk of recurrence to less than 3%, but is overtherapy for the majority of patients.

Patients with stage I non-seminomas and lymphovascular invasion in the primary tumor receive either active surveillance as well, with a risk of recurrence of approximately 50%, or one cycle of adjuvant chemotherapy with PEB, which reduces the risk of recurrence to less than 3%. Retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy as primary therapy for stage I nonseminomas is reserved for individual cases.

Prior to any adjuvant therapy of stage I seminomas and non-seminomas, determination of the tumor markers AFP, HCG and LDH is required. Patients with persistently elevated or even increasing tumor markers after orchiectomy are not considered to have stage I but metastatic tumor stage even in the absence of radiological evidence of metastases.

Therapy for metastasized stages

Patients with metastatic seminoma receive three cycles (“good risk”), rarely four cycles (“intermediate risk”) PEB, depending on the IGCCCG category. Patients with very limited abdominal lymph node metastases up to approximately 2 cm may alternatively be irradiated or included in the ongoing SAKK 01/10 trial for this stage if metastases are up to a maximum of 5 cm [3].

Patients with metastatic non-seminomas receive three (“good risk”) or four (“intermediate” and “poor risk”) cycles of PEB, depending on the IGCCCG category. Inadequate marker decline after the first cycle of therapy is an additional negative prognostic factor in “poor risk” patients. These patients may benefit from a complex, “dose-dense” combination therapy from the French GETUG working group [4].

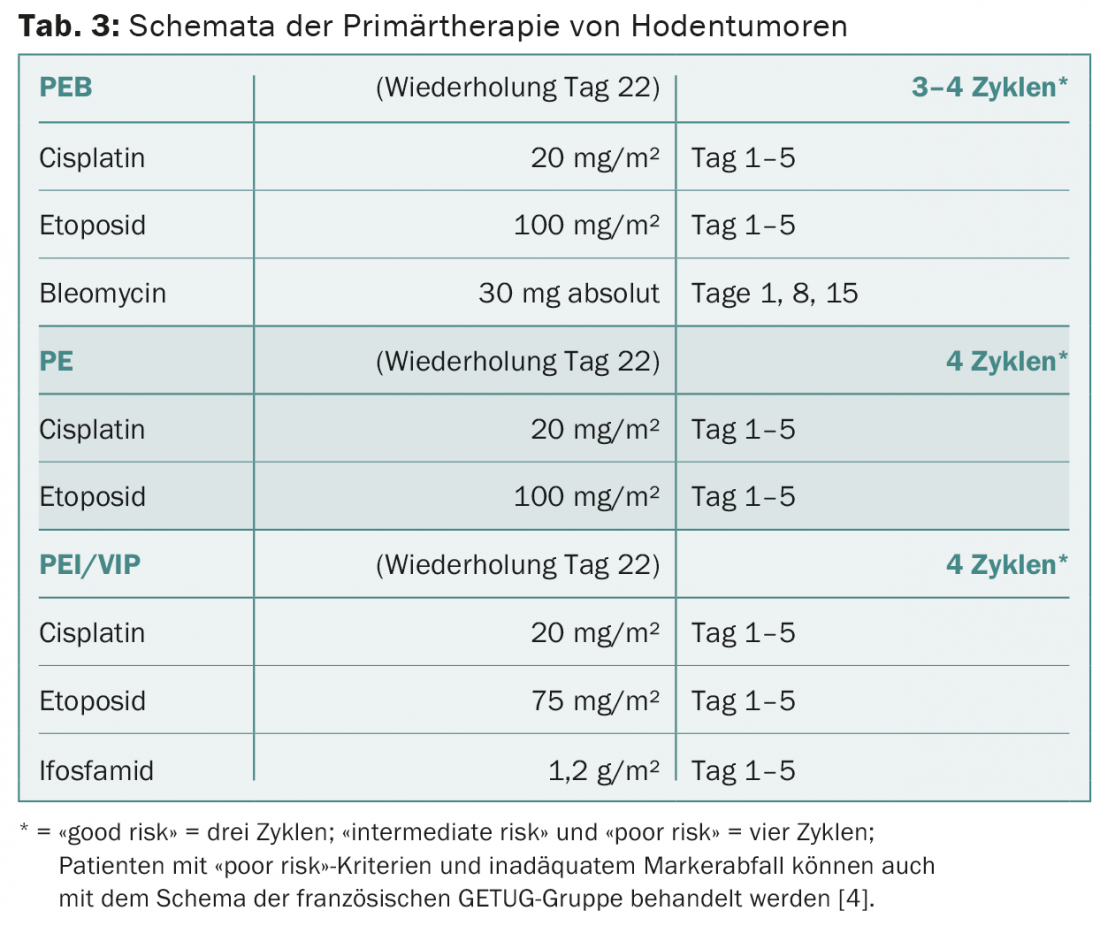

PEB is applied to seminomas and non-seminomas exclusively according to the standard regimen (Tab. 3) . The therapy intervals of three weeks must be observed. Bleomycin must be omitted in elderly patients and in patients with poor pulmonary or renal function. Patients with a favorable prognosis can be treated equally effectively with four cycles of cisplatin and etoposide without bleomycin instead of three cycles of PEB. In patients with intermediate or unfavorable prognosis, bleomycin must be replaced by ifosfamide. The decision to use primary high-dose chemotherapy is made on an individual basis for high-risk patients with primary mediastinal non-seminomas and for patients with liver, bone, or CNS metastases.

Therapy evaluation and resection of residual tumors.

In all patients with seminomas and non-seminomas, primary diagnostic tests are repeated approximately three weeks after the start of the last cycle of therapy. Intermediate staging is usually not required, and PET-CT has no value in therapy evaluation except in patients with pure seminoma and residual tumor after primary chemotherapy.

Patients with pure seminoma without complete remission after chemotherapy do not receive residual tumor resection, but PET-CT at the earliest 12 weeks after the start of the last chemotherapy. The further therapy decision is made individually depending on the PET findings.

Patients with non-seminomas without complete remission receive resection of all radiologically detectable residuals no later than four to eight weeks after initiation of the last cycle of chemotherapy. The further therapeutic decision is made individually depending on the histological findings.

Recurrence therapy

Treatment of patients with seminoma and non-seminoma and recurrence after therapy of stage I disease is analogous to the treatment algorithms for patients with primary metastatic disease, regardless of the choice of primary management. Usually, three to four cycles of PEB are used in these patients, depending on the tumor stage. The majority of these patients become permanently disease-free as a result.

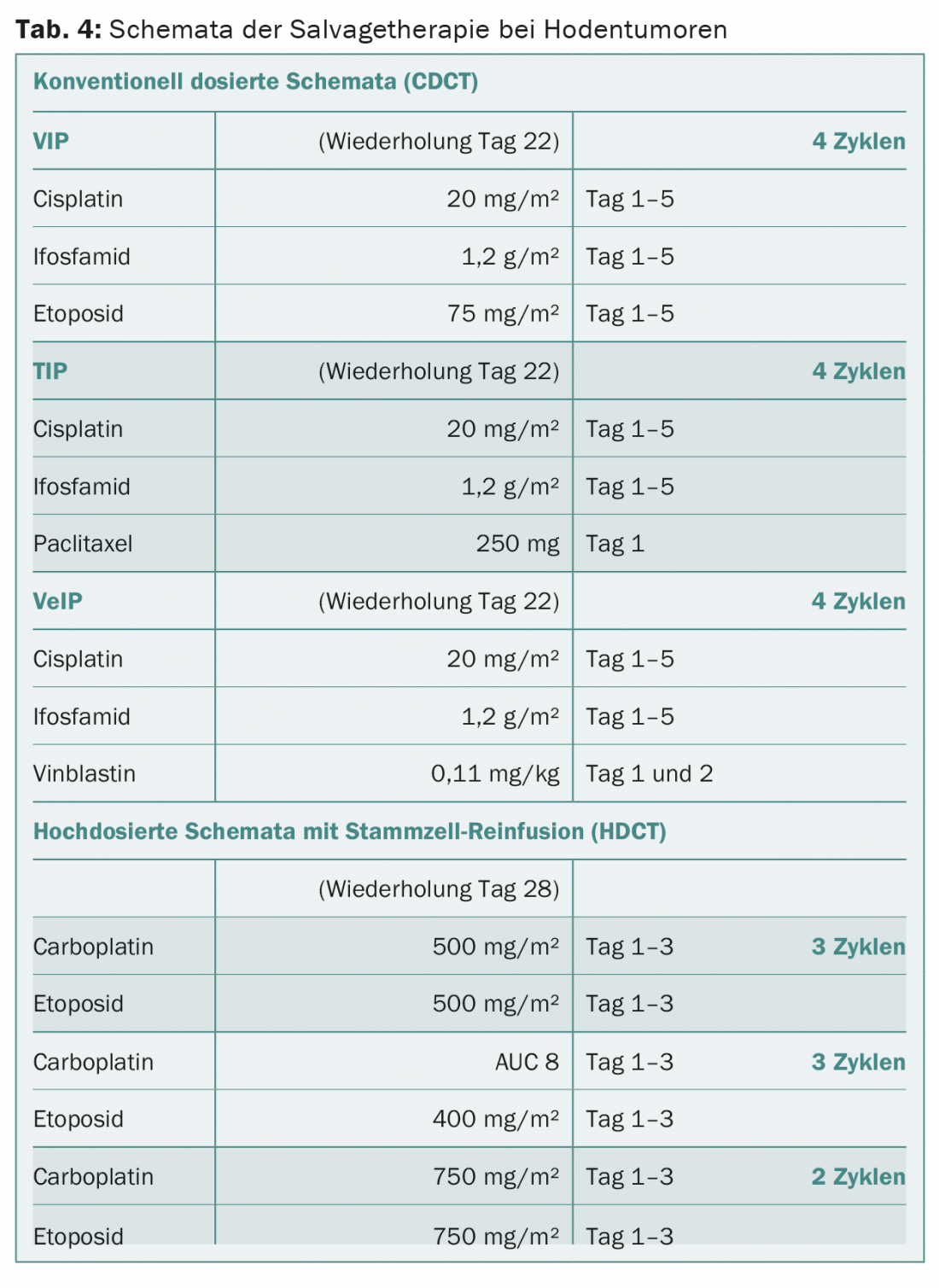

The much more intensive relapse chemotherapy (synonymously “salvage chemotherapy”) remains limited to metastatic patients who respond poorly to primary chemotherapy and do not achieve complete remission of their disease or who relapse from complete remission after primary chemotherapy. Two principal therapeutic strategies are considered: conventional-dose or high-dose chemotherapy (Table 4) . The best salvage strategy is determined on an individual basis.

Late relapses

Late relapses more than two years after primary chemotherapy are rare. Whenever possible, complete resection of late recurrence must be primary. The further procedure depends on the surgical result and the histological findings.

Palliative therapy

Palliative therapy is required in only a small number of patients. Well-documented effective cytostatic agents in the palliative setting are gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, and paclitaxel, both as single agents and as part of combination therapies. Palliative radiotherapy or “desperation surgery” may be indicated in individual patients.

Survivorship Care Plan

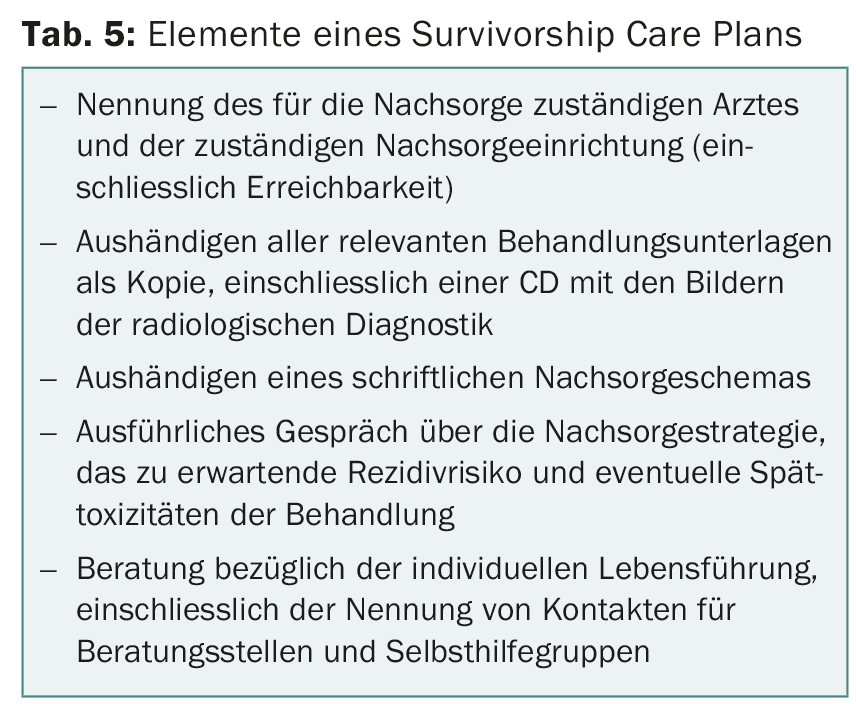

Patients in complete remission receive a final consultation at the end of therapy to develop a survivorship care plan that includes the items listed in Table 5.

Follow-up is performed according to the guidelines described by Cathomas et al. published follow-up schemes were performed [5]. If the persons concerned give their consent, the results of the examinations are included in the follow-up register. This includes not performing CT diagnostics in routine follow-up of patients two years after completion of treatment.

For more information: www.hodenkrebs.de

Literature:

- Beyer J, et al: Maintaining success, reducing treatment burden, focusing on survivorship: highlights from the third European consensus conference on diagnosis and treatment of germ-cell cancer. Annals of Oncology 2013; 24: 878-888.

- International Germ Cell Consensus Classification: A prognostic factor-based staging system for metastatic germ cell cancers. International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group. J Clin Oncol 1997; 15: 594-603.

- www.sakk.ch

- Fizazi K, et al: Personalised chemotherapy based on tumour marker decline in poor prognosis germ-cell tumours (GETUG 13): a phase 3, multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 1442-1450.

- Cathomas R, et al: Interdisciplinary evidence-based recommendations for the follow-up of testicular cancer patients: a joint effort. Swiss Medical Weekly 2010; 140: 356-369.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2016; 4(1): 34-37.