Family physicians are often the first point of contact for patients with eating disorders. Targeted screening questions based on the diagnostic criteria can be an aid in recognizing anorectic symptomatology of the restrictive or purging subtype. Family physicians also have an important role in the implementation of multimodal therapy and follow-up.

Eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa are underdiagnosed in primary care practices. A London study concluded that of 1000 primary care physicians studied, 50% did not diagnose a single eating disorder over the course of a year. This is with a point prevalence of all eating disorders of 5.7% in women and 2.2% in men. Furthermore, a follow-up study showed that when anorexia nervosa was clearly symptomatic, less than 70% of participating primary care physicians recognized it [1]. With this in mind, Dr. med. Christoph Rutishauser, Senior Physician for Adolescent Medicine at the Children’s Hospital Zurich, gave a lecture entitled “Anorexia nervosa – What General Practitioners Can Contribute to Successful Therapy” as part of the FomF (Forum for Continuing Medical Education) advanced training course in General Internal Medicine. He emphasized the importance of family physicians as often the primary point of contact and also their great importance in the therapy of already diagnosed anorexia nervosa.

Diagnostic clarification: What to look for?

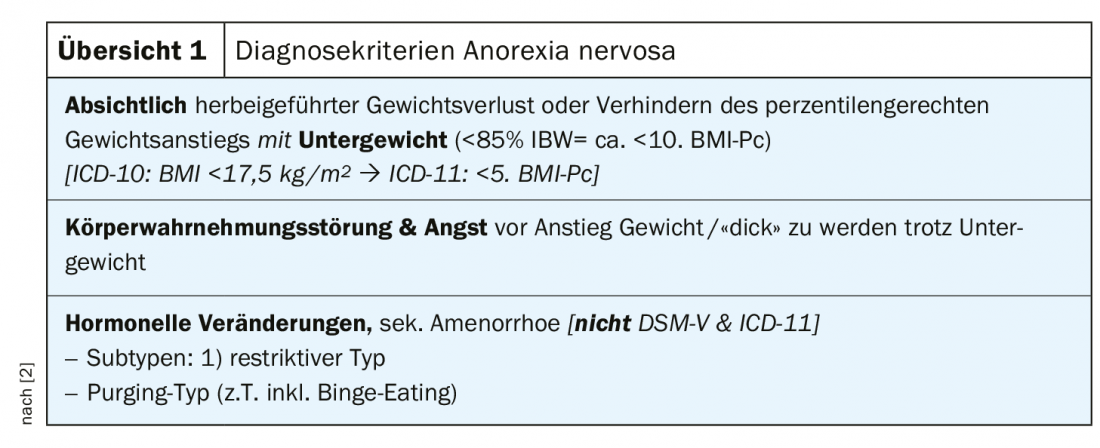

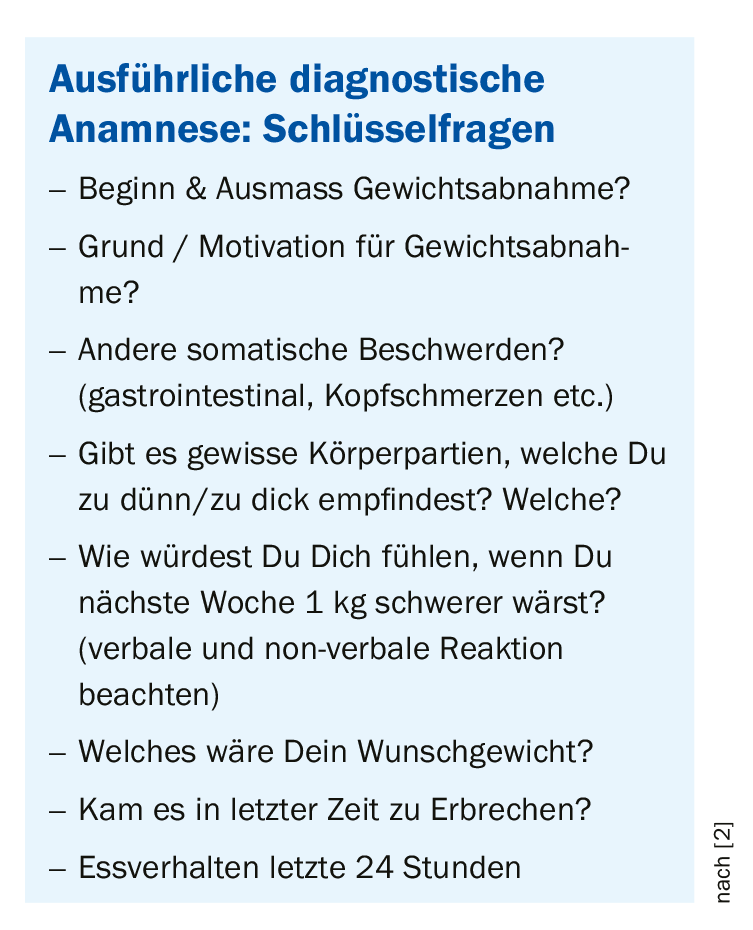

Knowledge of the diagnostic criteria (overview 1) is essential for correct diagnosis. This is because even though many cases of anorexia nervosa are primarily missed, it is also common to jump to conclusions about an eating disorder, especially in adolescent girls with weight loss. Essentially, the weight loss must be intentional and there must be a body image disorder with inappropriate fear of weight gain. There are two subtypes of anorexia nervosa. Whereas in the restrictive type weight loss is brought about exclusively by food deprivation, in the purging type other means such as vomiting or laxatives are used. In order to differentiate anorexia nervosa from other diagnoses, a detailed medical history is of utmost importance. The most important key questions are summarized in the box. It should be noted that patients often try to feign other diseases with weight loss. In addition to these key questions, if there is enough time, it can be helpful to ask about the depressed mood that is often observed, as well as social withdrawal. Somatic clarification should always be performed as well, whereby the more unclear the anamnesis, the broader this clarification should be. This includes a cranial MRI to exclude tumor if the history is not typical.

While at older ages the sex ratio is 10-15:1 in favor of females, this dominance is much less pronounced at 3:1 in younger adolescence. Because of the lower frequency and usually less typical presentation, many cases are missed in males. Thus, boys with anorexia nervosa often express a desire for a more masculine appearance and are less focused on weight. Nevertheless, they have an unreasonable fear of gaining weight. When taking a history, it is of great importance to address gender differences and not to dismiss the diagnosis based on gender. To clarify anorexia nervosa in boys and men, a cranial MRI should be performed in all cases.

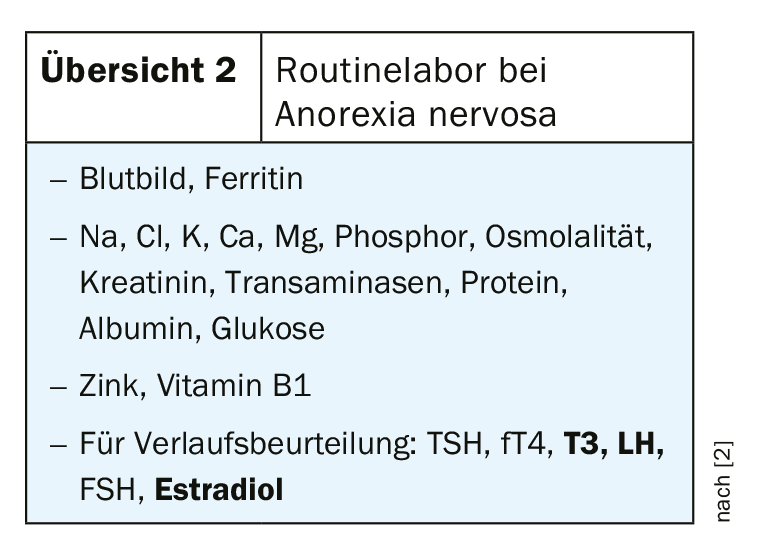

Physical examination in anorexia nervosa always includes heart rate and blood pressure, which are often forgotten as important parameters. It should be noted in particular that tachycardia or, in severely underweight patients, even a highly normal heart rate with simultaneous arterial hypotension may indicate a pericardial effusion and must be clarified by echocardiography. Pericardial effusions are common in the setting of anorexia nervosa and exist in approximately 40% of patients, but are usually not hemodynamically relevant. Weight should be assessed according to age using the BMI percentile curves and in no case using adult criteria. Because patients often try to cheat their weight up, sometimes drinking several liters of water to do so, signs of hyponatremia must be watched for. In this respect, specifying a minimum weight is at least critical. Dr. Rutishauser recommends checking electrolytes weekly initially and then every few weeks even, and especially, if weight is progressing well. This is also in view of a possible refeeding syndrome, which is most reliably manifested by hypophosphatemia. Furthermore, signs of self-injury and self-induced vomiting (enamel defects, parotid hypertrophy, hyperkeratotic PIP joint) should be looked for in the status. Overview 2 summarizes the routine laboratory for diagnosis of anorexia nervosa. T3 is often severely decreased with normal TSH and must not be substituted under any circumstances. In addition to status and laboratory, an ECG should be performed to rule out QT time prolongation.

Multimodal therapy and follow-up

Regarding the increased risk of osteoporosis in anorexia nervosa, bone densitometry is recommended after one year of underweight. The most important prophylaxis is weight normalization; calcium and vitamin D substitution is routinely performed, but its effectiveness has not yet been proven. Hormone replacement therapy is often discussed for prophylaxis, with oral contraceptives showing no benefit despite widespread use.

The therapy of anorexia nervosa aims at weight normalization. The weight to be achieved should be referred to as the “minimum healthy weight” rather than the “target weight” to prevent fear of further weight gain. When defining the minimum healthy weight, the circumstances before the onset of the disease, especially the initial weight, must be taken into account. Usually, a weight around the 25th BMI percentile is recommended as a target to induce normalization of estradiol and T3 and to achieve regular menstruation.

In the complex therapy of anorexia nervosa, there are some principles that are also important for home therapists. This includes an empathetic but factual and determined demeanor (“Firm Empathy”). Furthermore, food is medicine in this clinical picture and is thus prescribed by the physician, who also determines the dose of food. This should be emphasized to the patient to encourage compliance. Six meals a day are recommended, and communication about the amount eaten should be as calorie-free as possible. It is worth addressing bloating and stomach pain in an anticipatory manner and viewing them positively as signs of success. Initial thiamine substitution is recommended; all other vitamins and minerals should be added if deficiency is manifest. Ferritin may be elevated in the setting of underweight. Prognostically, early referral to a specialist is important, and initial steps such as meal prescription or exercise reduction should be initiated by the primary care physician. At least until a competent therapy is established, weekly check-ups by the primary care physician are very important and contribute to a successful outcome. Multi-professional care including the primary care physician has also proven beneficial in the longer course. Depending on experience, there are several opportunities for the primary care physician to participate in treatment. He or she may assume responsibility for all somatic aspects of the disorder in addition to psychotherapy, provide routine weekly checkups in coordination with an eating disorder specialist, or turn somatic checkups over to the specialist altogether. Role clarification and ensuring continuity of somatic care are important.

Indications for hospitalization are physical decompensation, for example a heart rate below 40/minute, acute mental deterioration, and insufficient success of outpatient treatment. A patient’s desire for hospitalization is usually a sign of exhaustion and should be taken seriously. In addition to physical control, psychoeducation and information about consequential damage is also the task of the somatician in charge and can contribute significantly to the success of the therapy. The average convalescence of anorexia nervosa lasts three to five years. If the disease persists for much longer, it is referred to as a chronic course, in which the focus is less on weight normalization and more on coping with everyday life and minimizing harm. In any form or stage of this eating disorder, the primary care physician can make an important contribution to the care of affected patients.

Source: FOMF AiM Update Refresher

Literature:

- Currin L, Schmidt U, Waller G: Variables that influence diagnosis and treatment of eating disorders within primary care settings: a vignette study. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(3): 257-262.

- Rutishauser CH: Anorexia nervosa: what family physicians can contribute to successful therapy, slide presentation. Dr. med. Ch. Rutishauser, Forum for Continuing Medical Education (FOMF), Update Refresher, General Internal Medicine, livestream 5/14/2020.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2020; 15(9): 50-51 (published 9/19/20, ahead of print).