“I like the combination of craft and intellectual understanding of complex procedures or the technology. Cardiac surgery is a specialty where you treat everyone from infants to elderly patients, so I liked that.” Prof. Dr. h.c., MD. Thierry Carrel, Clinic Director of the University Clinic for Cardiovascular Surgery in Bern, answers questions in an interview with journalist Nathalie Zeindler.

In “From the Heart,” heart procedures are described from the perspective of 20 patients. Prof. Dr. Carrel gives insights into his view of things in the operating room as well as about God and the world. In a personal conversation, the doctor was now available to answer questions of a very personal and rather politically weighted nature.

Is cardiac surgery routine or an art piece for you?

Prof. Dr. Carrel:

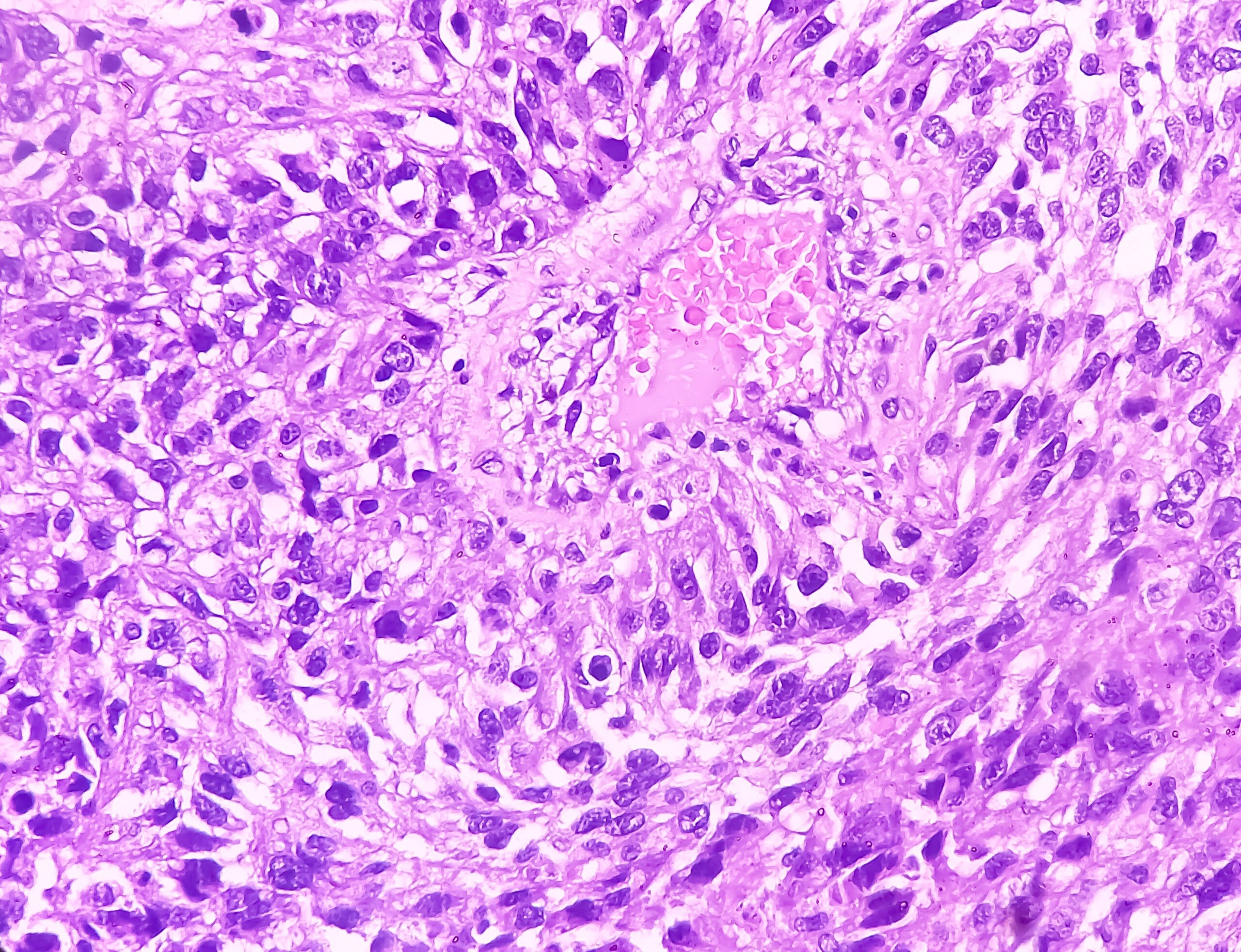

It’s a little bit of both. It’s a feat to get the heart off and on again during surgery. This is based on knowledge from natural science. But there is also a certain standardization. Routine is a difficult word – an operation doesn’t run itself, but procedures do run in a structured way. Everything is clearly specified. Space for art and creativity is only available in interventions due to congenital malformations.

Does the heart also have a religious character?

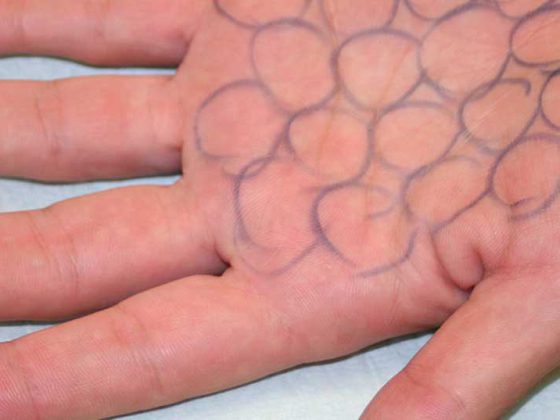

There is a lot of symbolism around the heart. It is a special organ because it is felt better and more often than other organs in the body in various life situations. Moreover, the symbolism around the heart has great tradition. A symbolic representation has been known for millennia in a wide variety of cultures. A religious character is not quite comprehensible for me in this. The supposed seat of the soul, which comes into play again and again in the context of the symbolic power of the heart, also remains open. I think ultimately there is something good about the fact that there are still mysteries about the human body.

How do you relate to your own heart?

I feel it like everyone else. I am not protected from heart disease because I work in cardiac medicine. We have long working days with sometimes stressful situations, so there must be a good balance to the work or to regenerate. In my role as a physician, I must also be a role model. I exercise and occasionally go to colleagues for a check up. If I had heart pain, I would get a normal checkup. In cardiac medicine, however, there are also insidious diseases that can lead to death without much symptomatology. Ultimately, a certain residual risk remains despite precautions.

How vulnerable are you yourself when confronted with difficult patient fates on a daily basis?

There are two aspects: The professional one as a surgeon who must encourage, gain confidence, give hope and motivate. In this workplace, you sometimes have to get over yourself when you witness bad situations. One must also come to terms with death. In today’s society, because of all the medicinal and technical possibilities, it is sometimes forgotten that what awaits us all without exception is death.

Away from the workplace, every doctor must be able to digest emotions on their own. That, too, is part of the job. As a boss, you tend to be alone in the upper hierarchical level, but we try to pass on support downwards, to the younger colleagues. Ultimately, everyone has to find their own way of dealing with these feelings.

Are you more and more lonely the higher you are positioned professionally?

Yes, that must be part of the disadvantage of being the boss. I have good contact with all the colleagues in my team, but I don’t want to burden them with my worries on top of their own burdens. As a boss, you have to be able to handle some things yourself.

Why did you choose cardiac surgery?

I like the combination of craft and intellectual understanding of complex processes or the technology. Cardiac surgery is a specialty where you treat everyone from infants to elderly patients, so I liked that. But part of it was also coincidence. In years of study a certain personality impresses you, this also contributes to the decision. As a teenager, I was fascinated by the implantation of the first artificial heart, Jarvik-7, in Salt Lake City. I found this almost more impressive than the transplantation of donor hearts. One advantage of artificial hearts is availability.

In addition, I personally enjoy being with people. In cardiac surgery, you quickly get to the core of a person, and conversations leading up to heart surgery often focus on life’s essential questions. Humans (with very few exceptions) value cardiac intervention more than any other intervention.

Personalities in cardiac surgery who have influenced me greatly are Prof. Dr. Marko Turina and his predecessor, Prof. Ake Senning. They were absolutely fascinating surgeons to me.

Burdensome surgery must be simplified in view of the increasing age of patients. Is this done in terms of minimally invasive procedures?

That’s a challenge. Life expectancy has increased significantly. There will be a significant increase in the elderly population, ergo the question arises what services the health care system will provide for the elderly. The goal is to have a good quality of life until shortly before death, to remain independent where possible, and to be as pain- or symptom-free as possible when a disease is present. Medically, in old age, one must weigh whether the intervention is suitable for the specific situation (presence of concomitant diseases, motivation of the patient). For this evaluation, a detailed personal interview is essential, preferably also with the relatives.

Do people even have time for such long conversations?

You can always find time, the only question is how long the day is. One is penalized by the billing system because the conversation is not well compensated unlike treatments. In a special situation, a conversation can sometimes be more important than surgery.

Is hospital financing a bad decision? Patients are discharged earlier and in some cases have to be readmitted, especially older patients.

Current funding is problematic for individual departments. There is always the question of how a particular service is remunerated. In cardiac medicine, services are compensated very decently.

In principle, of course, we have a great interest in not keeping the patient in hospital longer than is medically necessary, as this is followed by the important rehabilitation phase. In addition, in cardiac surgery, if a patient is readmitted with complications after a procedure within 21 days, this falls under the same case rate as the original procedure. This regulation is meant as a protection, so that not only the financial aspect is looked at and the complications are handed over to others. Bad decisions in discharges will always occur, as complications can develop later.

There are already problems with the current system, which was introduced in 2012: The hospital thinks in terms of business management. The turnover must be right, ideally there is no loss or much better a profit at the end of the billing period! economic thinking prevails in healthcare. Here, thoughts of economically questionable or questionable treatments in old age quickly arise. These questions are at the same time within an ethical framework. What medicine must not do under any circumstances is discriminate against patients. The framework for surgical interventions in the elderly has changed. Today, even an older but fit patient can be operated on who would not have been considered for it in the past simply because of his age.

Does highly specialized medicine also bring its pitfalls, as it is necessary to weigh up more precisely whether a specific operation can still be performed at a certain age or not?

Each generation has its own problems and advantages to deal with. It needs a discussion. People are generally allowed to grow older and enjoy better health for longer. Thus, new treatment issues emerge as we age. People simply like to live as long as the quality of life is right. Advising a patient who still has a lot of joy in life against surgery is very difficult. On the other hand, there are of course patients who are very sure that they no longer want curative therapy. This is where palliative care comes in. The importance of this specialty needs more attention to catch end-of-life needs away from EXIT.

Global budget – i.e. tariffs for medical services are reduced by a certain factor from a certain cost growth. What do you think about it?

We must constructively co-develop the system. One example is the massive oversupply of hospitals in Switzerland.

There are countless emergency stations in the city of Bern. Reasonable developments are needed here. Cooperation is required. Between public and private hospitals, you have to find a mode where you complement each other. It cannot be that one makes a profit and the others operate on complicated patients day and night. The small hospitals need to relieve the large ones for uncomplicated procedures/treatments.

Personalized medicine (Big Data) collects as much patient data as possible. What do you think of this development?

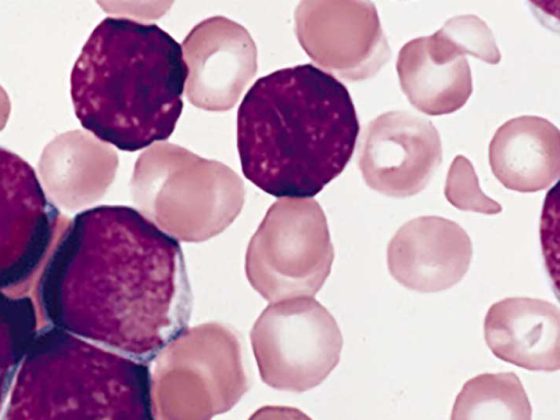

The bottom line is that this is probably very positive. However, the road to a functioning system is very long and, in the context of the collection of very personal data, associated with uncertainty on the part of patients. The goal is to create a digital risk profile of everyone for certain diseases by analyzing part of their genetic makeup. In this way, preventive care could be used in an even more targeted manner. Personalized medicine seeks to better define a risk in order to filter out the patients most at risk or those who will best benefit from a particular therapy.

Organ donation and organ shortage – what is the current situation?

You can’t force anything on a society that it doesn’t want. But: In Switzerland, we lose several dozen people every year because there are not enough organs available. There are different angles here as well. Fewer donors also means fewer fatal accidents.

Currently, the extended consent is practiced. The deceased would therefore have to have expressed consent in principle to the donation during his or her lifetime or, if unknown, this decision is transferred to the next of kin after death.

One consideration was the introduction of an objection solution: Only those who object are not eligible as organ donors; all others are potential donors.

Currently working on a “presumed consent” initiative. This would separate the process of deciding to donate in time from the acute death. One positive effect of missing donors is the industry’s effort to find replacement solutions, such as better drugs or artificial hearts.

What moved you most in the creation of the book (“From the Heart”)?

That patients had the willingness to talk about their medical history at all, in a non-anonymized form and with pictures. I think many felt the need to describe these interventions from the patient’s point of view for once. Information brochures for patients are in fact otherwise often very neutral and reflect the doctors’ ideas.

Excerpt from the interview with Nathalie Zeindler

Editorial office Dr. med. Katrin Hegemann

CARDIOVASC 2017; 16(6): 23-24