Ovarian cancer has become a chronic disease. Therapy sequences with surgery, additive and palliative systemic therapies, plus maintenance therapies in different lineages are complex. Discussing current data helps to translate it into clinical practice.

Ovarian cancer has become a chronic disease, therapy sequences with surgery, additive and palliative systemic therapies, plus maintenance therapies in different lines are complex. How should we apply all this new data to our everyday lives? The recently published ESMO/ESGO guidelines [1] provide helpful guidance. This review article reports on what’s new and important in 2019.

Ovarian cancer, 90% of which is epithelial in origin, is the gynecologic tumor with by far the highest mortality in industrialized countries. In Europe, about 65,000 women contract the disease each year, and about 42,000 die from it. Unfortunately, in approximately two-thirds of cases, the diagnosis continues to be made only at advanced stages (FIGO III, IV), when the disease has already spread outside the pelvis. Then, the 5-year survival is only about 20-30% [2]. Unfortunately, we do not have screening examinations for early detection that would improve prognosis (e.g., transvaginal ultrasound, tumor marker determinations [CA-125]) [3]. Intensive efforts are being made to improve the prognosis of women suffering from ovarian cancer with optimized therapy approaches. There is still a great need for action here.

Primary treatment

Surgery or chemotherapy: which comes first? Maximal cytoreductive surgery aiming at macroscopic tumor freedom at the end of surgery is crucial for prognosis [4].

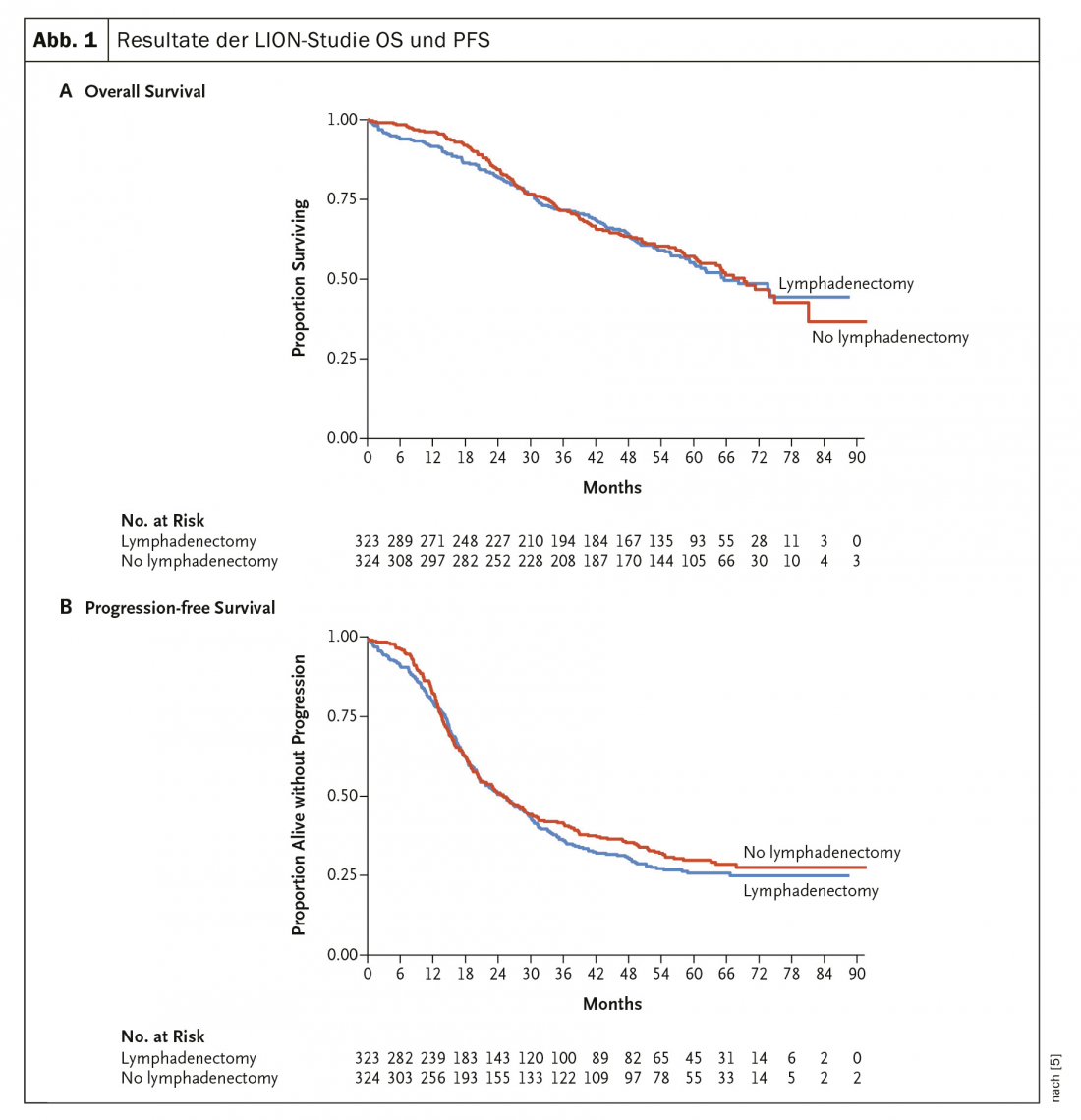

In 2019, the (long-awaited) results of the LION trial [5] were published, which investigated the value of routine lymphadenectomy in advanced ovarian cancer (Fig. 1) . Neither PFS nor OS showed any difference in this randomized trial. Thus, systematic paraaortic and pelvic lymphadenectomy for preoperatively and intraoperatively unremarkable lymph nodes in the case of complete resection is no longer recommended. In advanced stages, additive chemotherapy with carboplatin and taxol is standard.

Should surgery now be performed first followed by chemotherapy, or is there evidence that patients benefit from primary systems therapy followed by surgery? An EORTC study and the CHORUS study [6,7] showed comparable results for both options in terms of PFS and OS in patients with stage IIIC or IV disease.

Accordingly, the ESMO/ESGO recommendation is now that a primary surgical approach should be chosen (UDS, upfront debulking surgery) if macroscopic tumor freedom can be achieved (based on pre-operative staging) and acceptable morbidity is assumed [1]. If this is not the case, primary systemic therapy should be given.

However, the partial lack of expertise of the surgeons in these studies is often criticized, which is why an international multicenter study (Trial on Radical Upfront Surgical Therapy TRUST) is currently being conducted in which the participating surgeons must qualify according to selected criteria. Results are expected in approximately 2024.

What options do we have to improve prognosis with the available systems therapies? The Japanese study JGOG3016 showed that with a so-called dose-dense treatment with weekly paclitaxel 80 mg/m2 in combination with carboplatin, a clear improvement in median progression-free survival as well as overall survival could be achieved compared to standard treatment [8]. Nevertheless, this therapy regimen is hardly applicable in Europe due to significant toxicity, so the newly revised ESMO/ESGO guidelines do not recommend this for patients in Western countries [1].

Bevacizumab in first-line treatment.

Bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody, is approved in combination with chemotherapy in the so-called high-risk setting, in the most common type of ovarian cancer, high-grade serous (HGSC). Post-operative residual tumor formations ≥1 cm or a FIGO stage IV are considered high risk. Bevacizumab has been shown to improve PFS in multiple randomized trials. A survival benefit was only described in the ICON7 study [9,10]. There is no known predictive biomarker for bevacizumab therapy.

Maintenance therapy in the first line

Bevacizumab is used in high-risk settings first in combination with additive chemotherapy and then as maintenance at a dose of 15 mg/kg or 7.5 mg/kg every 3 weeks for max. 15 months recommended [1,9,10].

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors: approximately 50% of epithelial ovarian carcinomas (EOC) exhibit deficient DNA repair mechanisms via homologous recombination. This circumstance also explains the strong effectiveness of the board at the EOC. PARP inhibitors lead to so-called synthetic lethality in HR-deficient cells. However, they also show efficacy in patients without proven defects in the HR genes. Several PARP inhibitors have been tested (olaparib, niraparib, rucaparib, and others).

The results of the SOLO1 trial, which showed a 70% improvement in PFS versus placebo in BRCA-mutated patients on first-line olaparib maintenance therapy [11,12], attracted considerable attention. Genetic counseling and testing (in a timely manner) with regard to olaparib maintenance in this setting is now strongly recommended [1].

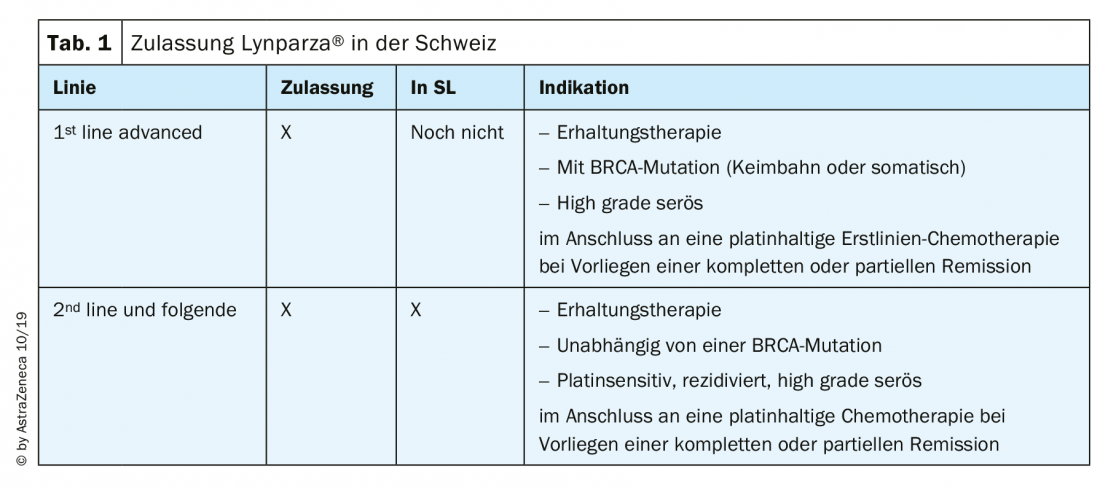

The two most frequently used substances in Switzerland, olaparib (Lynparza®) and niraparib (Zejula®), are approved and available for ovarian cancer as follows (Tab. 1): Niraparib has been approved by health insurance since August 2019 for maintenance therapy in relapsed platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer, regardless of BRCA mutation status [13]. Numerous data on PARP inhibitors were presented at ESMO 2019 and are now the subject of intense discussion.

Practical procedure for first-line treatment

At our clinic, we now offer all patients with non-mucinous ovarian cancer to receive genetic counseling and testing for BRCA1/2 mutations (mostly germline, rarely somatic). This usually takes place during additive chemotherapy. In case of BRCA1,2 mutation olaparib is used as maintenance, in case of BRCA wild type at most maintenance therapy with bevacizumab is used if bevacizumab was already used during chemotherapy.

In the case of platinum-sensitive relapse, maintenance therapy with niraparib can be followed, regardless of BRCA1,2 mutation status. In a possible further recurrence, we then use bevacizumab, in combination with platinum if still sensitive.

Genetic testing is clearly recommended in the ESMO/ESGO guidelines, both because it is predictive of response and because it allows healthy family members to be counseled and tested early [1].

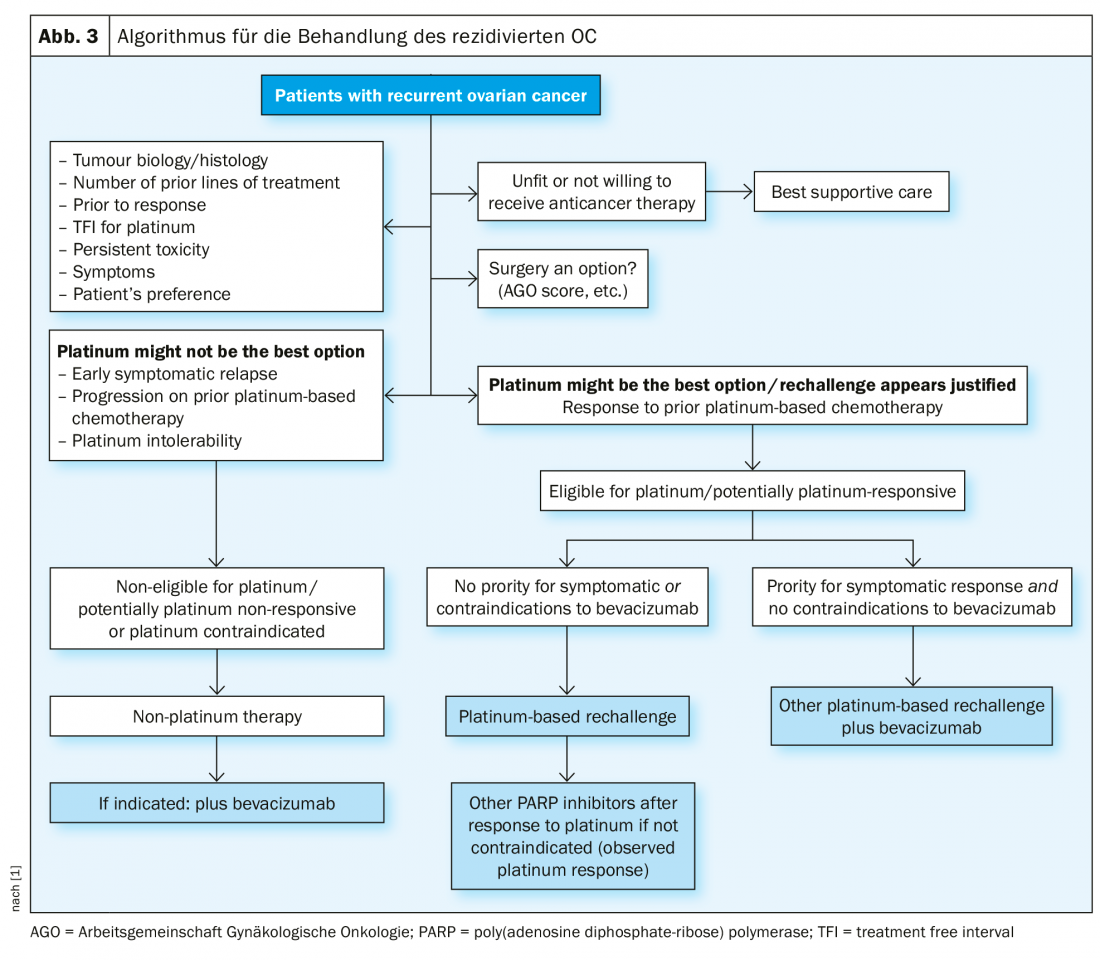

Recurrence treatment

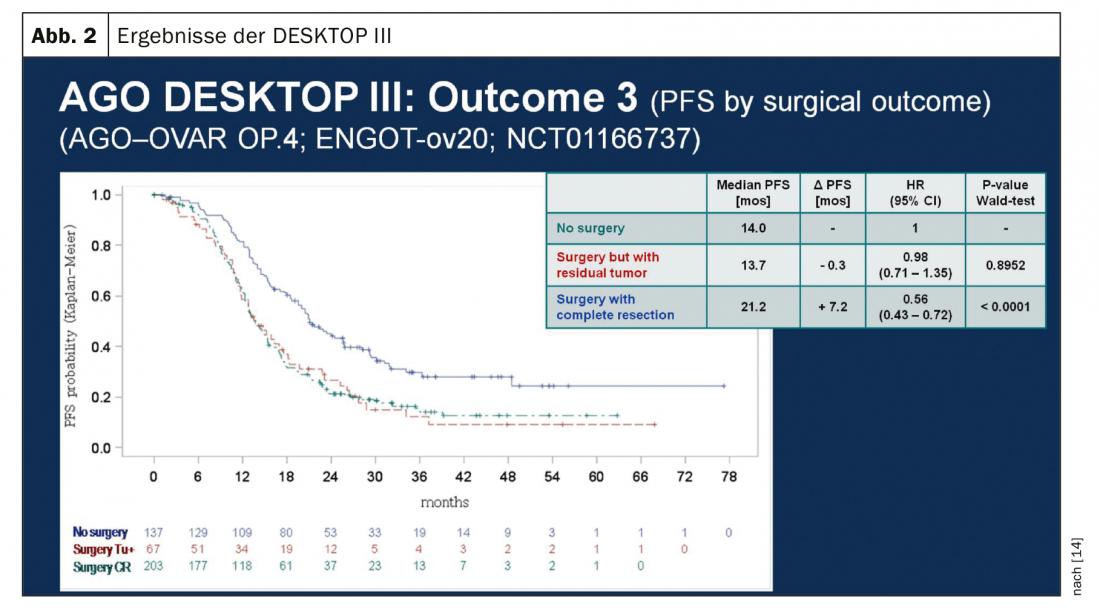

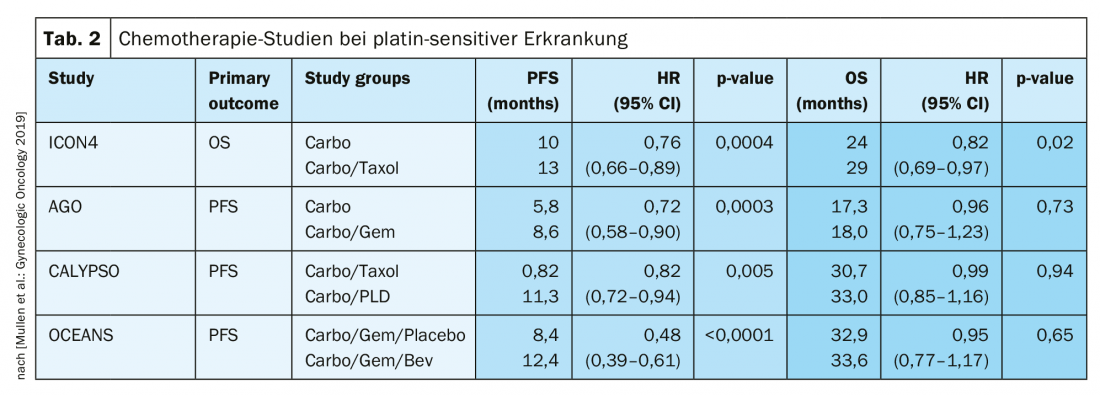

In platinum-sensitive recurrence, repeat cytoreductive surgery is a therapeutic option if it can achieve macroscopic tumor freedom. Results of the Gynecologic Oncology Study Group (AGO) DESKTOP III investigation demonstrated an improvement in PFS with surgery exclusively when complete surgical excision could be achieved [14]. OS data are not yet published (Fig. 2). In case of platinum sensitivity, numerous combination therapies have been tested (Tab. 2).

Platinum sensitivity is redefined

In the past, a 6-month interval after the last platinum therapy was considered a strong indication of renewed sensitivity to platinum. However, this does not reflect that this period should rather be seen as a continuum. The term platinum eligibility was chosen for this. The definition of platinum resistance is new:

-

Confirmed platinum resistance: progression under platinum-containing chemotherapy.

- Suspected platinum resistance: early symptomatic recurrence with low probability of further response to platinum [1].

In this therapeutically difficult situation, platinum-free therapy regimens are an option, possibly in combination with bevacizumab [15]. Incidentally, at ASCO 2018, it was presented that re-administration of bevacizumab improves PFS, even if previously used [16].

PARP inhibitors

In the relapse setting, a response to platinum is the best predictive marker for the efficacy of PARP inhibitors as maintenance therapy. Maintenance therapy with olaparib after platinum-containing chemotherapy showed PFS improvement in patients with BRCA1/2 mutations in the so-called Study 19 [17] and in the SOLO2 study [18]. Other PARP inhibitors followed, e.g. niraparib (NOVA trial [19], rucaparib (ARIEL3 [20]).

The NOVA trial clearly demonstrated that PFS was improved with niraparib compared with placebo in both patients with BRCA mutations and wild-type, although the benefit was greatest in patients with BRCA mutations. The studies for maintenance therapies with olaparib and niraparib also indicated that the time to next chemotherapy can be significantly prolonged. This is a clinically absolutely significant endpoint. PARP inhibitors are generally well tolerated, and dose reductions are occasionally necessary (Fig. 3).

Summary

First-line therapy of epithelial ovarian cancer (mostly high-grade serous) consists of surgery and platinum-based chemotherapy as standard. Patients should be offered early genetic counseling and (somatic or germline) testing, especially since maintenance therapy with olaparib significantly improves progression-free survival in BRCA1,2-mutated patients. Bevacizumab is continued as maintenance if it has already been used in combination with additive chemotherapy.

In platinum-sensitive recurrence (new definition, so-called platinum-eligible), a renewed surgical procedure can be considered under certain conditions, followed by platinum-containing chemotherapy, possibly in addition bevacizumab (which can then be continued as maintenance). After response to platinum in the relapse setting, the PARP inhibitor niraparib is approved in Switzerland for BRCA-mutated and wild-type patients. When platinum is no longer indicated, platinum-free therapeutic regimens are also available. Immunotherapy for ovarian cancer is currently undergoing rapid development, and no substance has yet been approved as standard therapy [21].

Take-Home Messages

- Ovarian cancer is the gynecologic tumor with the highest mortality in the Western world.

- Complex sequences with surgery and systems therapies improve prognosis and quality of life.

- Maintenance therapies with bevacizumab and PARP inhibitors are available.

- The newly published ESMO/ESGO Guidelines provide information on current therapy recommendations.

- Additional indications for PARP inhibitors are expected in the future (1st line, BRCA-unmutated).

- Immunotherapy is being investigated in numerous phase III trials worldwide – it is not yet a standard of care in the treatment of ovarian cancer.

Literature:

- ESMO-ESGO consensus conference recommendations on ovarian cancer: pathology and molecular biology, early and advanced stages, borderline tumors and recurrent disease N. Colombo, C. Sessa, et al. Annals of Oncology 30: 672-705, 2019.

- THE-WORLD-OVARIAN-CANCER-COALITION-ATLAS-2018.pdf, at www.worldovariancancercoalition.org

- Screening for Ovarian Cancer, US Preventive Services Task Force JAMA. 2018

- du Bois A, et al: Role of surgical outcome as prognostic factor in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer Cancer 2009.

- Harter P, et al: A Randomized Trial of Lymphadenectomy in Patients with Advanced Ovarian Neoplasms LION NEJM 380; 9 February 28, 2019.

- Vergote I, Tropé CG, Amant F, et al: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or primary surgery in stage IIIC or IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2010.

- Kehoe S, Hook J, Nankivell M, et al: Primary chemotherapy versus primary surgery for newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer (CHORUS): an open-label, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2015.

- Katsumata N, et al: Long-term results of dose-dense paclitaxel and carboplatin versus conventional paclitaxel and carboplatin for treatment of advanced epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer (JGOG 3016): a randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Oncol 2013.

- Burger RA, et al: Incorporation of bevacizumab in the primary treatment of ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2011

- Perren TJ, et al: A phase 3 trial of bevacizumab in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2011.

- Murai SY, Huang B, Das A, et al: Trapping of PARP1 and PARP2 by clinical PARP inhibitors, Cancer Res. 2012.

- Moore K, et al: Maintenance Olaparib in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Advanced Ovarian Cancer. NEJM Oct 2018.

- www.spezialitaetenliste.ch

- Du Bois A, et al: Randomized controlled phase III study evaluating the impact of secondary cytoreductive surgery in recurrent ovarian cancer: AGO DESKTOP III/ENGOT ov20. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35(15_Suppl): 5501.

- Pujade E, et al: Bevacizumab Combined With Chemotherapy for Platinum-Resistant Recurrent Ovarian Cancer: The AURELIA Open- Label Randomized Phase III Trial, JCO May 2014.

- Pignata S, et al: Chemotherapy plus or minus bevacizumab for platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer patients recurrent after a bevacizumab containing first line treatment: the randomized phase 3 trial MITO16B-MaNGO OV2B-ENGOT OV17. J Clin Oncol 2018;36(15_Suppl).

- Ledermann JA, et al: Olaparib maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive relapsed serous ovarian cancer: a preplanned retrospective analysis of outcomes by BRCA status in a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014.

- Pujade-Lauraine E, et al: Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017

- Mirza MR, et al: Niraparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2016.

- Coleman RL, et al: Rucaparib maintenance treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled,phase 3 trial, Lancet 2017.

- Marth C, et al: Immunotherapy in ovarian cancer: fake news or the real deal? Int J Gynecol Cancer 2019.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2019; 7(6): 6-10.