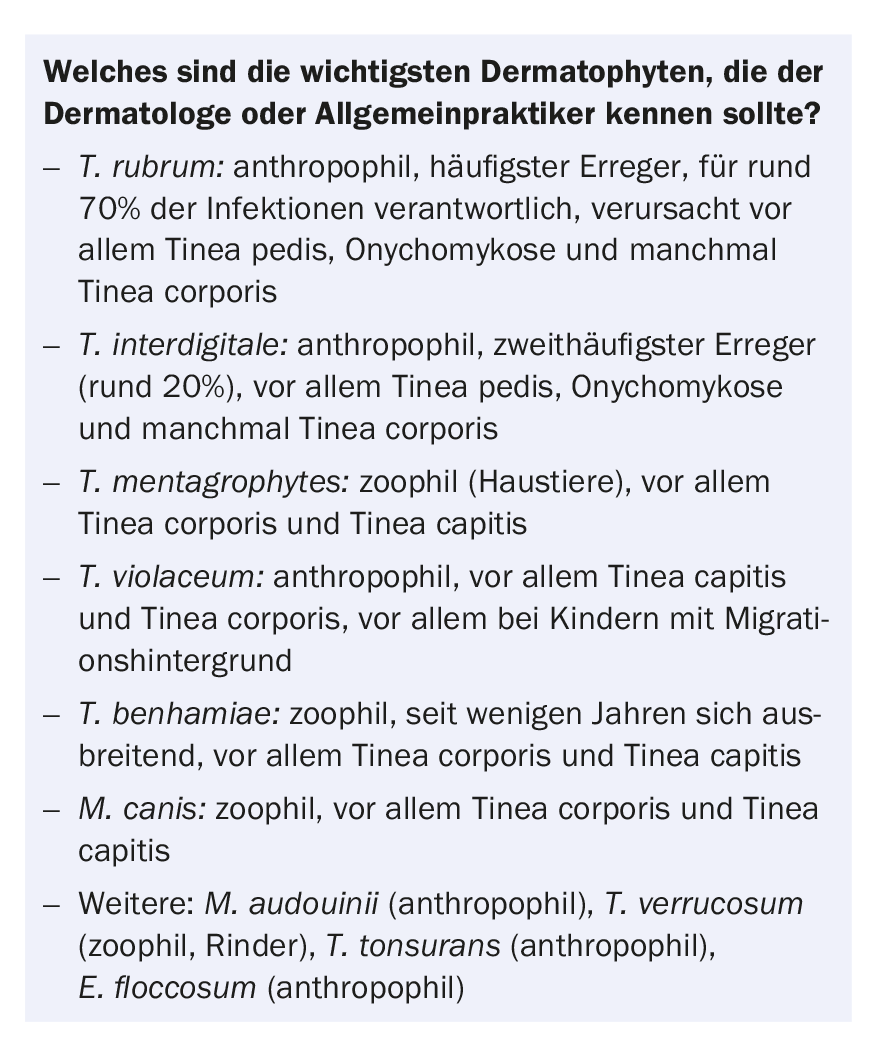

Dermatophytes cause infections of the exposed skin, nails or hair. T. rubrum and T. interdigitale are the most common dermatophytes, are anthropophilic and causative agents of tinea pedis, nail mycoses and sometimes tinea corporis. Tinea capitis primarily affects prepubertal children and is caused by zoophilic or anthropophilic pathogens. An increase has been observed in recent years. The direct microscopic slide and culture are the main diagnostic methods, with culture taking three to four weeks. It is important to provide the laboratory with suspected diagnosis and information such as travel history, underlying diseases, animal contacts, etc.

Fungal infections of the skin can be caused by dermatophytes, yeast and mold. In terms of numbers, dermatophytes account for the largest proportion. The infection is then called dermatophytosis or tinea (English “ringworm”). Dermatophytoses are among the most common infections worldwide, affecting between 2-20% of the population, depending on the study [1,2].

They are keratinolytic fungi that can live exclusively on keratin-containing structures and therefore can only infect the free skin and its adnexes such as hair follicles, hair and nails. Based on their natural habitat, dermatophytes are divided into geophilic species, which occur naturally in soil, zoophilic species, which occur on animals, and anthropophilic species, which occur only on humans.

In the following, the different clinical manifestations are briefly presented, interesting epidemiological trends in Switzerland and worldwide are explained, taxonomic changes are explained, and important and new aspects of diagnosis are presented.

Clinic

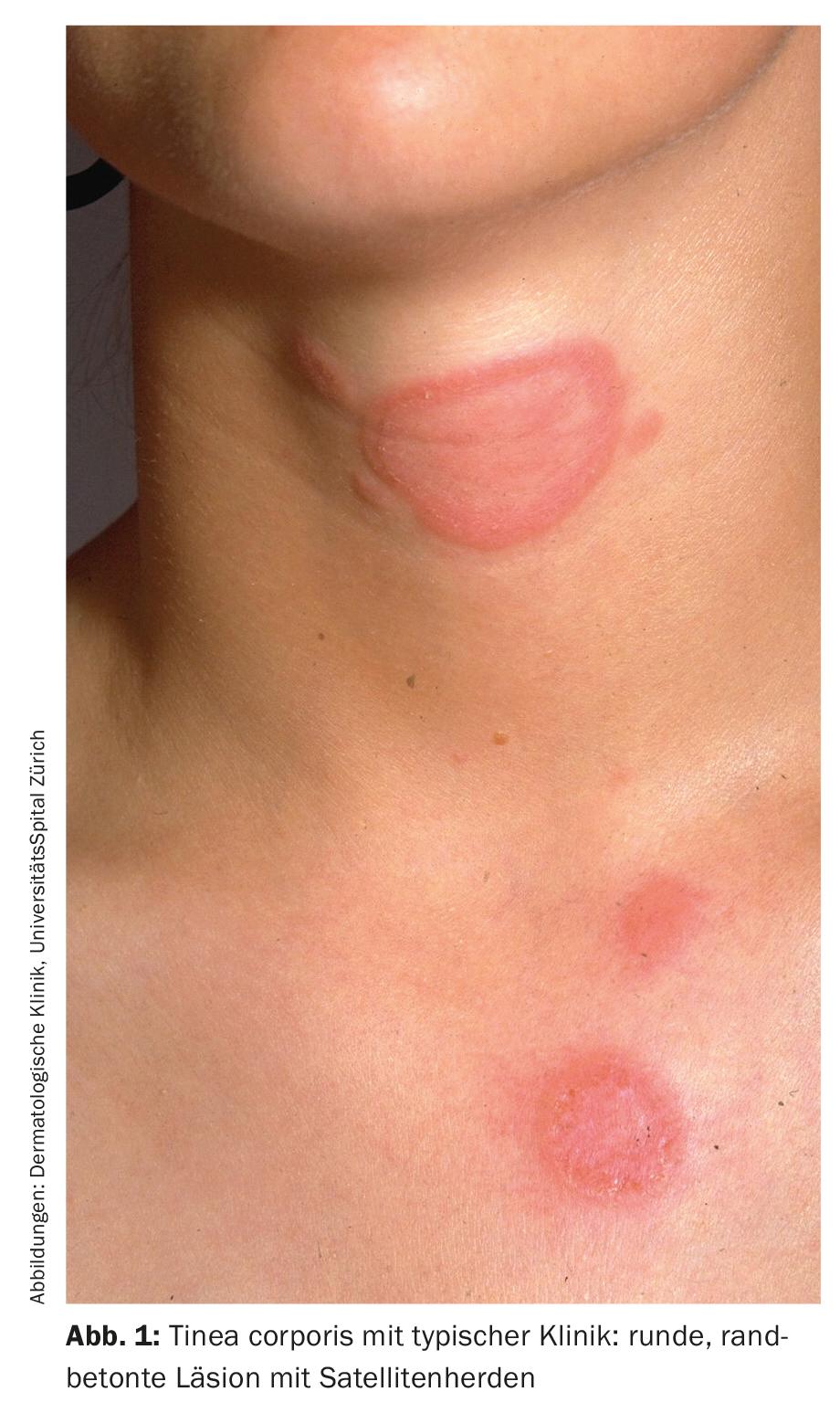

Dermatophytoses (tinea) are called e.g. tinea pedis (foot), tinea capitis (hairy scalp), tinea faciei (face) or tinea corporis (body) depending on the localization. Except on the nails, tinea typically presents with roundish, marginal, scaling erythema, central paling, and centrifugal spread (Fig. 1) [3].

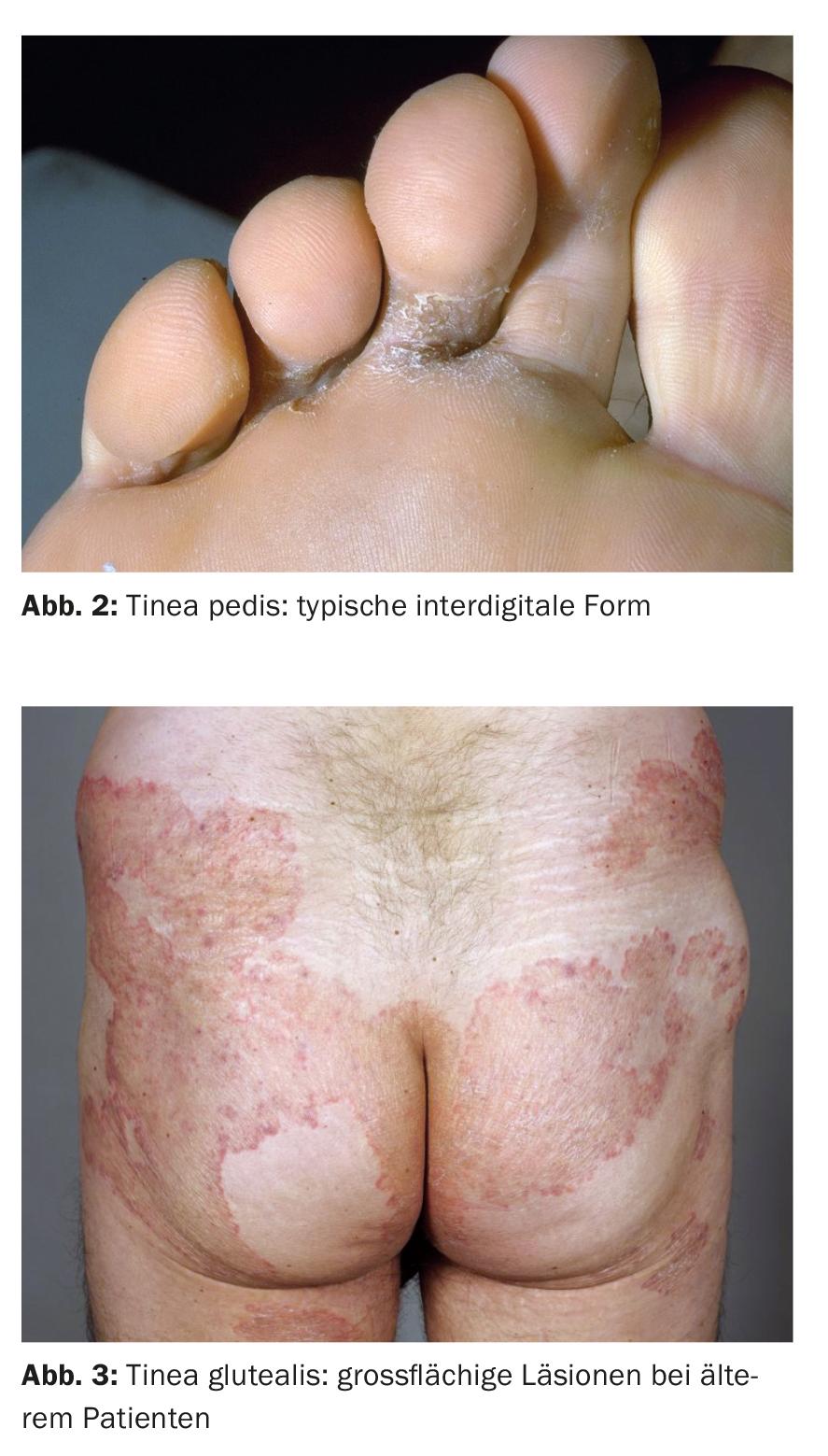

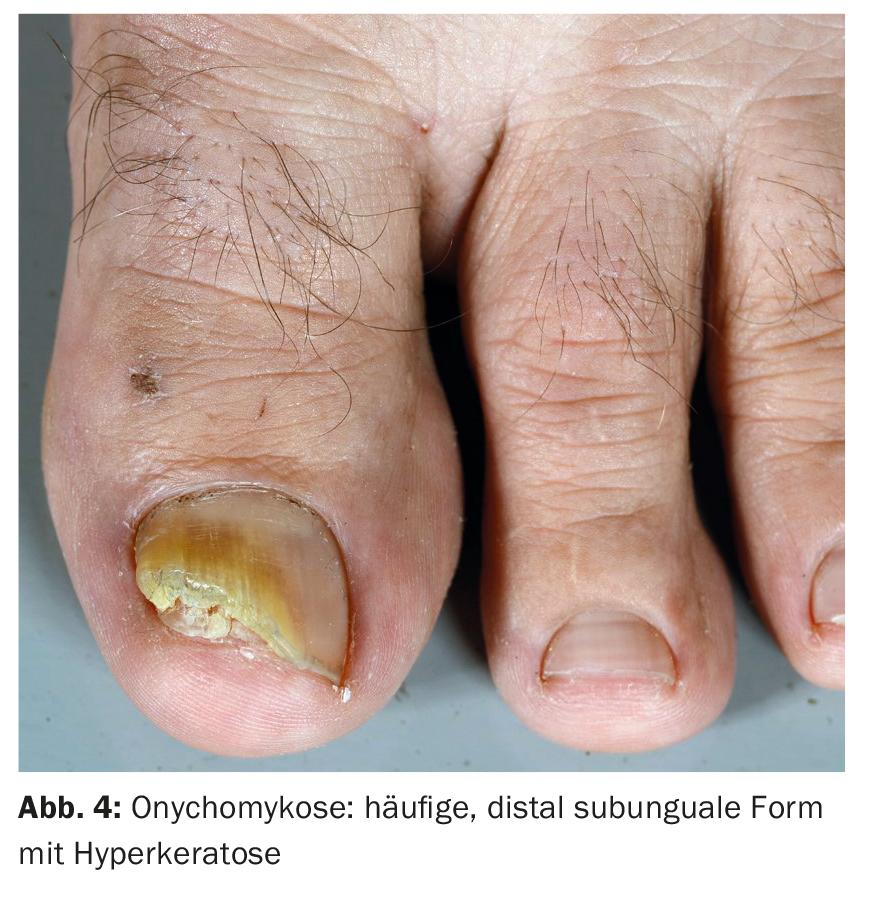

Satellite foci and asymmetric distribution may be further indications of infection. The frequent interdigital form of tinea pedis is characterized by redness, scaling, fissure formation and maceration in and around the interdigital spaces (Fig. 2) . If infestation of the sole and lateral edges of the foot with hyperkeratosis and partial redness is present, it is referred to as the “moccasin type”. Autoinoculation (especially when putting on and taking off underpants and underpants) can lead to the development of tinea inguinalis and tinea glutealis (Fig. 3) . Differential diagnosis of tinea corporis must include nummular eczema, atopic dermatitis, parapsoriasis, psoriasis, subacute lupus erythematosus, or impetigo.

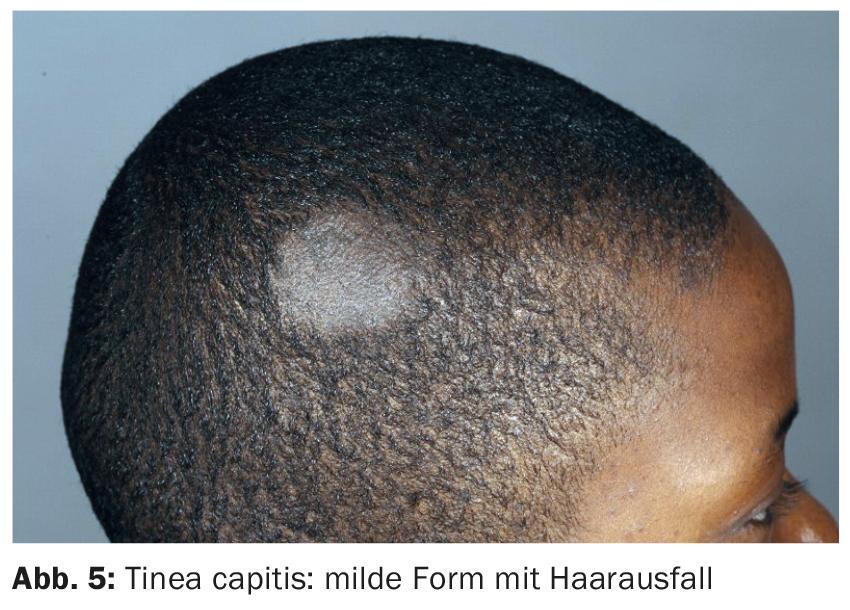

In nail mycosis (onychomycosis), the toenails are affected five times more often than the fingernails. The most common manifestation is the distal subungual form with thickening of the nail plate (hyperkeratosis) and color change, which can be whitish, yellowish or brownish (Fig. 4). In rare cases, infection occurs in the proximal nail area or so-called superficial white onychomycosis.

Tinea capitis, which occurs mainly in childhood, affects the hair and scalp. Depending on the species, the fungi penetrate the hair shaft (endotrichous form) or infect the outside of the hair and multiply there (ectotrichous form). Mild forms of tinea capitis present as circular, scaly changes with hair loss (Fig. 5). The disease caused by zoophilic pathogens is usually more severe and may be characterized by strong inflammatory reactions up to a kerion celsi. As a result of folliculitis, irreversible scarring can occur if the diagnosis is made too late.

Taxonomy

Traditionally, dermatophytes have been divided into three genera, Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton. However, new sequence data combined with ecological and phenotypic criteria have now led to a newly valid nomenclature that is on the one hand more complex, but on the other hand also clearer [4]. The main changes are:

- Newly, seven genera are distinguished: Trichophyton, Epidermophyton, Microsporum, Nannizzia, Paraphyton, Lophophyton and Arthroderma.

- Only the first four genera are clinically relevant

- T. interdigitale persists as a species name for the anthropophilic strains (causes mostly nail mycosis and tinea pedis)

- The zoophilic T. interdigitale strainsare grouped under the name T. mentagrophytes, as in the past

- The rare, mainly geophilic Microsporum species are grouped under Nannizzia

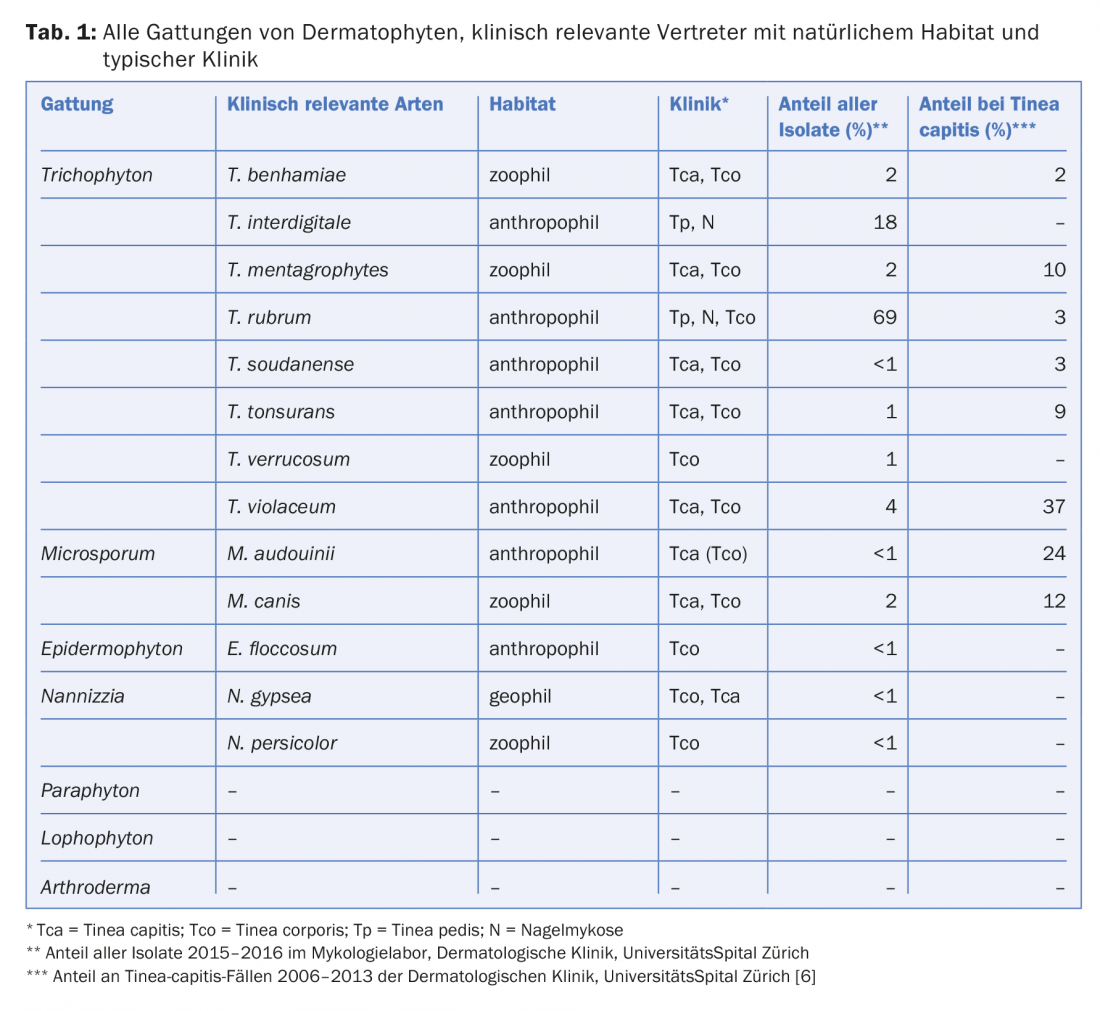

Table 1 gives an overview of all genera, important representatives of them and the typical clinic.

Epidemiology

Over the past 100 years, the spectrum of dermatophytes has changed markedly. In the early 20th century, Microsporum audouinii and Trichophyton schoenleinii (both tinea capitis), Epidermophyton floccosum (tinea corporis), and Trichophyton interdigitale (nail mycosis, tinea pedis, and tinea corporis) were the dominant species [2,5]. In parallel with increased recreational sports activities in gymnasiums and indoor swimming pools and greater migration after World War II, the prevalence of tinea pedis also increased sharply, whereas improved hygiene and the use of griseofulvin decreased the number of tinea capitis cases. In the same course, the pathogen spectrum also changed; T. rubrum became the dominant species worldwide in nail and foot mycosis and in tinea corporis, followed by T. interdigitale. In the case of tinea capitis, T. rubrum became the dominant species in Europe, probably due to the strong increase in domestic animals in the second half of the 20th century. Century, the zoophilic species M. canis dominant.

Data from our specialized dermatomycology laboratory on all samples submitted in the last two years also show a clear dominance of T. rubrum; 68.5% of all isolated dermatophytes involve this species (Tab. 1). 20% are due to T. interdigitale. 85% of the samples with T. rubrum and T. interdigitale were from mycoses pedis (nails and tinea pedis), the rest were from tinea corporis and mycoses of the hand (nails and tinea manuum).

The analysis of tinea capitis cases is interesting: Overall, we have observed an increase in recent years [6]. This is particularly due to an increase in infections with T. violaceum in children with a migrant background. About three quarters of the tinea capitis cases are caused by anthropophilic pathogens (T. violaceum, M. audouinii, T. tonsurans, T. soudanense) . In the zoophilic cases, transmitted mainly by domestic animals , M. canis, T. mentagrophytes, and T. benhamiae are the causative agents (Table 1).

Diagnostics

Laboratory diagnostics are essential for the detection of fungal infection. Correct preanalytics is a prerequisite for successful laboratory testing. It is particularly important that the mushroom evidence is explicitly requested and that additional information is provided. Submitting physicians are asked to provide suspected diagnosis and information such as travel history, underlying diseases, animal contacts, etc [7]. This information is important for the correct processing of the samples and for the interpretation of the results. For example, it is important to note that the tinea corporis patient is a farmer; T. verrucosum in particular is then sought here, resulting in additional culture media and longer incubation.

The following applies to sampling [7]:

- Clean lesion/removal site with 70% alcohol beforehand if possible

- In case of nail mycosis, remove nail chips and friable subungual nail material as far proximally as possible

- In the case of tinea corporis, scrape off scales from the marginal area of the cutaneous lesion,

- For tinea capitis remove dandruff and epilated hair with hair root

- Store specimens in a dry place and ship them using the shipping packages provided (e.g. Dermapak®).

It must be emphasized again and again that specimen material should be taken generously, because otherwise the sensitivity of the examination cannot be guaranteed.

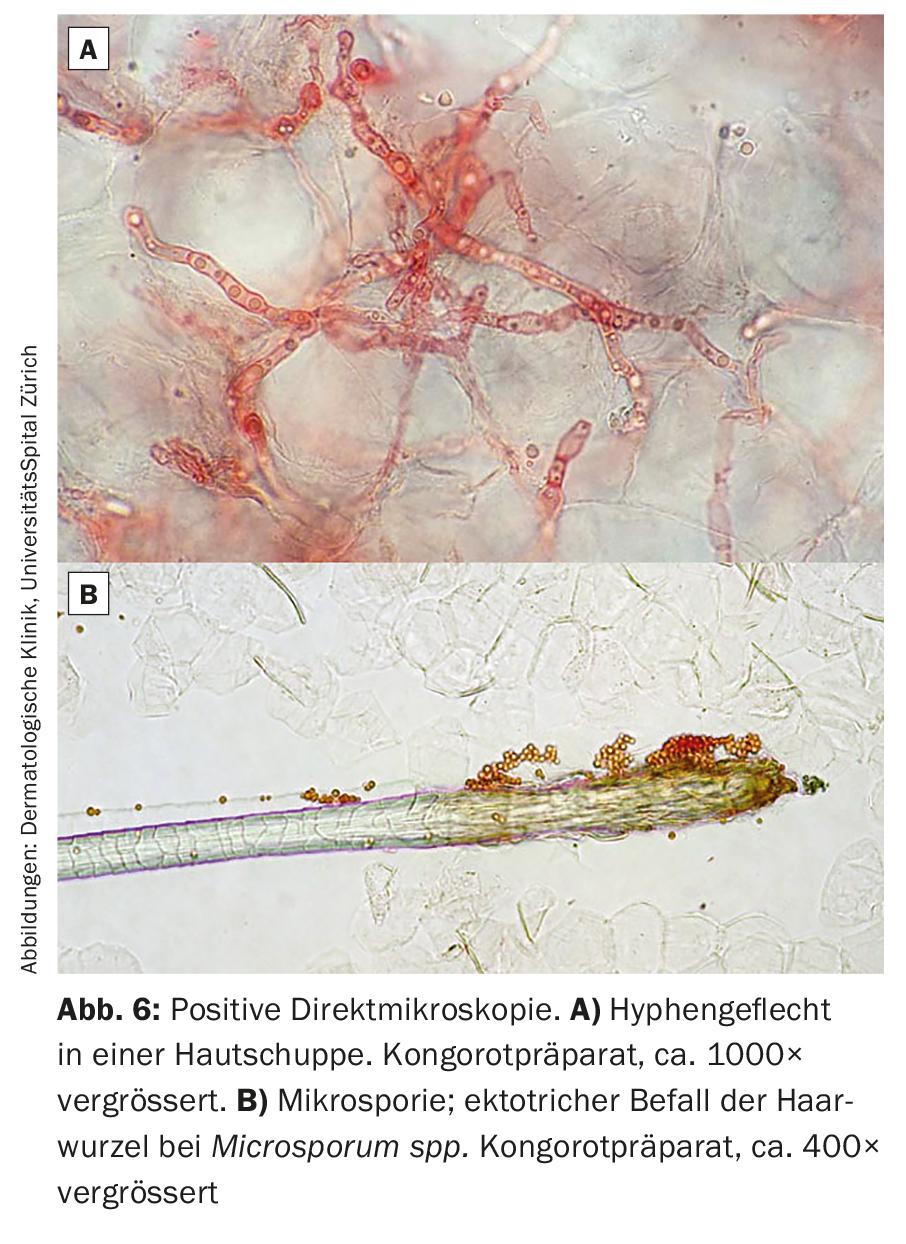

In the laboratory, direct microscopy is performed and a culture is established on several culture media. The direct microscopic preparation is inexpensive and the result is available within a short time. The detection of fungal elements (hyphae, arthroconidia) proves a fungal infection (Fig. 6). The sensitivity is in the range of 75-80% and a negative result therefore does not exclude a fungal infection. In addition, microscopy alone cannot provide information on the type of pathogen, which is important with regard to further investigations, e.g. for zoophilic pathogens. The established cultures must be incubated for three to four weeks because dermatophytes grow slowly [8]. If T. verrucosum is a possible pathogen, it is recommended to incubate even six to eight weeks. In individual cases, if suspicion persists and culture and microscopy are negative, histologic examination with PAS staining may be helpful. In the next few years, molecular biological methods will probably be increasingly used, which are fast and sensitive, but also expensive.

Literature:

- Havlickova B, Czaika VA, Friedrich M: Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses 2008; 51(Suppl 4): 2-15.

- Hayette MP, Sacheli R: Dermatophytosis, trends in epidemiology and diagnostic approach. Curr Fungal Infect Rep 2015; doi:10.1007/s12281-015-0231-4.

- Borelli S, Lautenschlager S: Dermatophyte infection of the skin and nails. Ther Umsch 2016; 73: 457-461.

- de Hoog GS, et al: Toward a Novel Multilocus Phylogenetic Taxonomy for the Dermatophytes. Mycopathologia 2016; doi:10.1007/s11046-016-0073-9.

- Zhan P, Liu W: The Changing Face of Dermatophytic Infections Worldwide. Mycopathologia 2016; doi:10.1007/s11046-016-0082-8.

- Kieliger S, et al: Tinea capitis and tinea faciei in the Zurich area – an 8-year survey of trends in the epidemiology and treatment patterns. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015; 29: 1524-1529.

- Bosshard PP: Diagnosis of fungal infections. Ther Umsch 2016; 73: 449-455.

- Bosshard PP: Incubation of fungal cultures: how long is long enough? Mycoses 2011; 54: E539-E545.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2017; 27(1): 10-15