More and more people in western industrialized countries are suffering from obesity, and the trend continues to rise. Regular physical activity can help control weight.

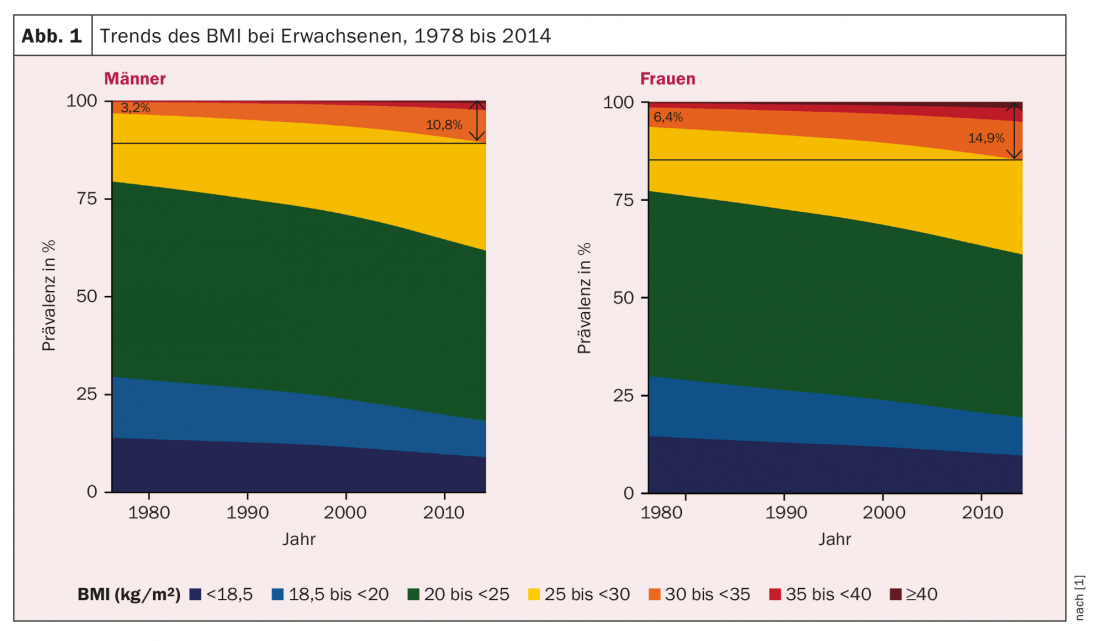

More and more people in industrialized countries suffer from obesity. The approximate extent has been quantified by a meta-study on development trends regarding BMI in adults, which compared data from two hundred countries from 1975 to 2014. In the pool of a total of 19.2 million participants, there was a significant increase in obesity grade I to III over the observation period (Fig. 1) . If this trend continues, global obesity prevalence is expected to reach 18% in men and >21% in women by 2025 [1]. With an increase of overweight people by 30.8% and obese people by 10.3% since 1992, this trend is also evident in Switzerland. Against this background, weight control programs are becoming increasingly important.

The focus is on prevention

The basic principle, according to Davide Malatesta of the Institute of Sport Sciences at the University of Lausanne, is energy balance: the relationship between energy intake and consumption. If this balance tips into the positive range, the body mass increases. This is made possible on the one hand by physical inactivity (in 2016, this applied to 27.5% of the world’s population [2]), and on the other hand by the changing dietary culture. Access to larger quantities of inexpensive, processed foods promotes “oversaturation” [3].

Physical activity influences a whole range of factors related to energy balance. However, there is a strong individual variability regarding the weight-reducing effect of exercise, and sometimes this effect is even doubted in principle [4]. In fact, the effects of exercise as a sole measure on weight are rather marginal; possible weight loss is up to two kilograms. However, such exercises become effective when combined with calorie restriction, where a reduction of up to 13 kg can be achieved. The duration of the performance also plays a role: 150 minutes per week is enough to maintain or improve the state of health. Clinically significant weight loss is achieved at exercise durations of 225-420 minutes per week [5].

Malatesta therefore emphasizes, “The central role of physical activity is to increase cardiorespiratory fitness and overall health.” Prevention of chronic disease and reduction of mortality are the primary goals, weight reduction a desirable but secondary effect.

The vacuum cleaner as a fitness device

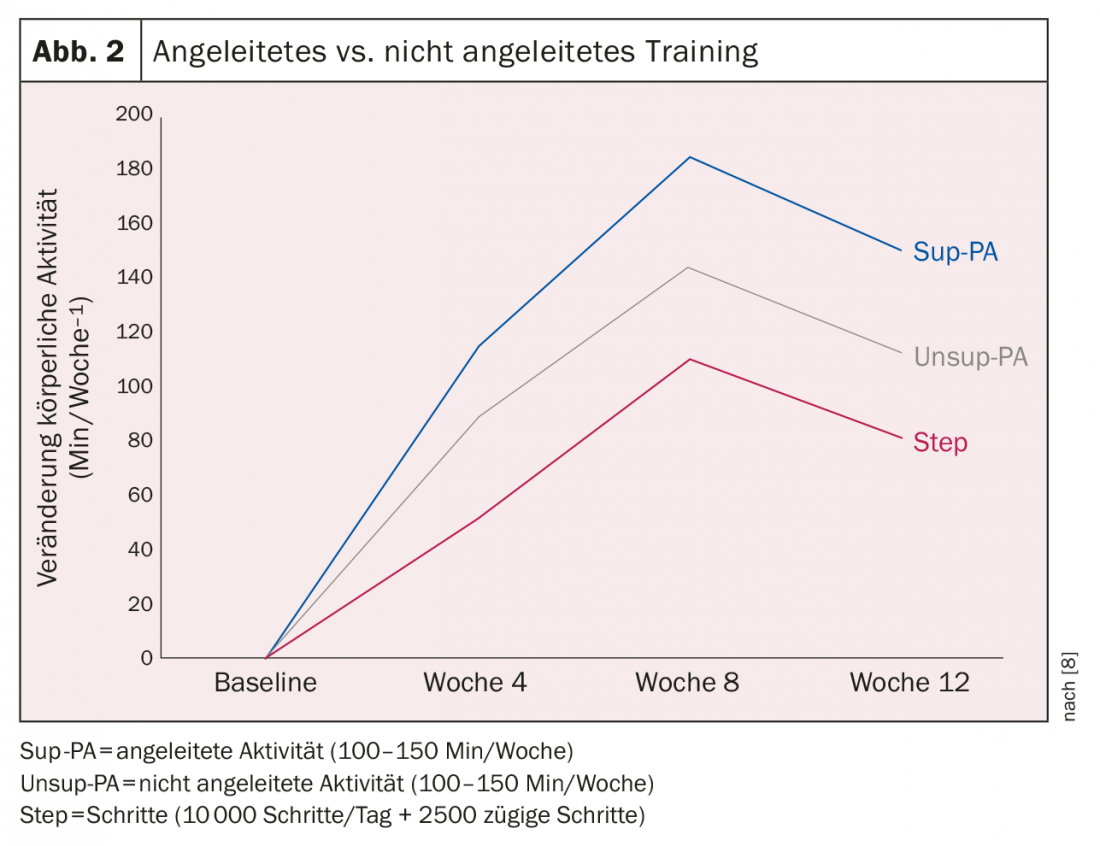

Caspersen et al. defined physical activity in 1985 as any type of physical activity that burns calories [6]. This applies not only to planned sports sessions, but equally to the commute to work by bike, the walk to the nearest supermarket or housework. Since obese people sit about 160 minutes more per day compared to normal weight people, they consume about 350 ±65 kcal less energy per day [7]. Therefore, non-athletic exercise is of high importance. This must be easy to implement and integrate into everyday life. A low-threshold way to stimulate thermogenesis is to wear functional shoes (“unstable shoes”), which are characterized by a rounded sole or air cushion. This is because whether the activity is guided or not plays a minor role: even walking, combined with caloric restriction, leads to a weight reduction of 5-6% (Fig. 2) [8].

MICT or HIIT?

When it comes to targeted training for weight reduction, the question often arises as to which form is better: endurance training (“moderate-intensity continuous training”, MICT) or resistance training (“high-intensity interval training”, HIIT). While MICT (60-70% HRmax) focuses on gaining and/or maintaining lean mass, HIIT (≥90% HRmax) aims to burn body fat through intervals of high exertion and energy output. The workouts are especially effective when combined with caloric restriction. MICT tends to be used more frequently for weight management programs.

In collaboration with the Istituto Auxologico Italiano, the Department of Physiology at the University of Lausanne compared the effect of MICT versus HIIT in patients with grade II and III obesity (n=19) over two weeks [9]. Both groups showed a significant increase in aerobic fitness and fat oxidation rate. The increase in aerobic fitness occurred slightly more significantly with HIIT (+8%). Therefore, HIIT is better suited to achieve early promotion in this regard, Malatesta concludes. Because HOMA2-IR was significantly reduced only with MICT (-24%), MICT is an indispensable tool to train insulin sensitivity. Thus, HIIT and MICT are complementary tools for improving aerobic and metabolic fitness. It is also important for compliance to diversify the training program.

But be careful: Compensation mechanisms of the body can destroy the desired training effect – weight reduction. This may be due to a reduced basal metabolic rate, increased metabolic efficiency and increased energy intake. To prevent this, 300 minutes of physical activity must be done per week. This corresponds to ≥3000 kcal [10]. Accordingly, the speaker concluded that physical activity must be moderate to intense and performed for at least 300 minutes per week to achieve long-term weight loss and minimize weight reabsorption.

Source: SGED Annual Meeting, November 15-16, 2018, Bern.

Literature:

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC): Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19.2 million participants. Lancet 2016; 387(10026): 1377-1396.

- Guthold R, et al: Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1.9 million participants. Lancet Glob Health 2018; 6(10): 1077-1086.

- Swinburn BA, et al: The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 2011; 378(9793): 804-814.

- Blundell JE, et al: Appetite control and energy balance: impact of exercise. Obes Rev 2015; 16(Suppl. 1): 67-76.

- Swift DL, et al: The Role of Exercise and Physical Activity in Weight Loss and Maintenance. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2014; 56(4): 441-447.

- Caspersen GJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM: Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep 1985; 100(2): 126-131.

- Levine JA, Kotz CM: NEAT – non-exercise activity thermogenesis – egocentric & geocentric environmental factors vs. biological regulation. Acta Physiol Scand 2005; 184(4): 309-318.

- Creasy SA, et al: Effects of supervised and unsupervised physical activity programmes for weight loss. Obes Sci Pract 2017; 3(2): 143-152.

- Lanzi S, et al: Short-term HIIT and Fat max training increase aerobic and metabolic fitness in men with class II and III obesity. Obesity 2015; 23(10): 1987-1994.

- Flack KD, et al: Energy compensation in response to aerobic exercise training in overweight adults. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2018; 315(4): R619-R626.

CARDIOVASC 2019; 18(1): 34-35 (published 7.2.19; ahead of print).